Rescue in the Biblical Negev

024

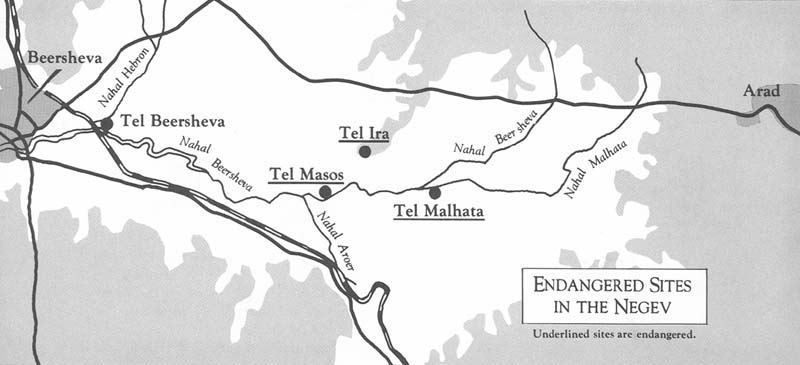

As work begins on the infrastructure required to relocate the Israeli army’s bases and training facilities from Sinai to the Negev—in accordance with the Middle East peace agreements—Israel’s archaeological institutions have been mobilized to survey and excavate on an emergency basis threatened sites in the area. Beginning February 1, 1979, salvage excavations began on three of the most important sites in the Negev—Tel Malhata, Tel Masos and Tel Ira. All three are known to have been occupied for long periods in antiquity and lie within the area destined to become the northern airfield of the Negev. The report which follows, by the coordinator of the salvage effort, Moshe Kochavi, describes the significance of these three sites in the Beersheva valley and the progress of Israel’s effort in this endeavor during 1979. Digging will continue throughout this spring and summer. Volunteer inquiries should be directed to Marta Rettig, Assistant to the Director, Israel Department of Antiquities, P.O.B. 586, Jerusalem, Israel 91000.

Immediately after the signing of the Israel-Egyptian peace agreements in Washington last spring, Israel’s archaeological institutions undertook a complete survey of sites in the Negev. Among the thousands of ancient sites found, most were “one period” sites, that is, they were inhabited for a short time only and then abandoned. The survey team discovered, recorded—and, in some cases, excavated nomadic settlements of the Bronze Age, agricultural hamlets clustered around Iron Age forts, and scores of prehistoric sites which indicated that the Negev “dried up” only a few thousand years ago. Such is the nature of the finds in the Negev highlands.

But the picture is different in the northern Negev, in the fertile loess valleys stretching from Arad on the east to Gaza in the west, with Beersheva, the capital of the Negev, at their center. Here, both surface runoff and underground water were sufficient to support long-term habitation, so this line formed the 025southernmost line of permanent Israelite settlements. The Beersheva plain is drained by a stream called Nahal Beersheva, running east to west. Often swollen with winter floods, but dry in summer, the water seeps underground to supply the wells of the ancient mounds still visible on the banks of the nahal or wadi. When the river bed is dry as it is for almost all of the year, a bucket on the end of a rope sometimes more than 100 feet long, can still find water underground.

At the beginning of this year, the Institute of Archaeology and the Department of Classical Studies of Tel Aviv University, the Department of The Land of Israel studies of Bar-Ilan University, and Ben-Gurion University’s Department of Archaeology began a crash program to survey and excavate the Beersheva valley. I coordinated the joint effort in which both students and faculty took part. We received extensive help, too, from the Israel Museum, Hebrew Union College of Jerusalem and the Hebrew University.

Tel Malhata is the central site in the valley. All the dusty trails of the valley lead here, to the foot of the tell where several ancient wells are clustered. Undoubtedly the wells are why today it is the main gathering place for the Bedouin of the region, and, in antiquity, were the reason for the establishment of a settlement here.

The modern Hebrew name for the site, Malhata, derives from the Latin ‘Moleatea,’ the name of the fort constructed during Roman times which still crowns the summit of the tell.

The Biblical identity of Malhata is uncertain. Some think that Malhata may be Moladah, one of the towns included in the Negev inheritance of the tribe of Judah (Joshua 15:26). Others identify Malhata with Hormah whose conquest and settlement are attributed to Simeon. Yohanan Aharoni thought Malhata was the site of Canaanite Arad, and I have suggested that it is Baalat-beer, described in Joshua 18:8 as belonging to the inheritance of Simeon. The sheer number and variety of these suggestions indicates both the deep interest prompted by Tel Malhata and, at the same time, the paucity of our knowledge about the site.

From probes made some years ago we know that Malhata was first inhabited in the Middle Bronze Age IIB (17th–15th centuries B.C.), and that there are no remains here from the Late Bronze Age (15-13th centuries B.C.), the period of the Israelite conquest. In fact, the tell was not resettled before the reign of King Solomon in the 10th century B.C. The settlement flourished throughout the period of the Israelite monarchy (10th–6th centuries B.C.), until it was finally destroyed at the end of the First Temple period. The most interesting remains from this period 026are the massive defenses—earthen ramparts, a moat, and stone retaining walls. But because both the tell itself and the surrounding area are the burial ground of the local Bedouin, trial excavations in the area containing these remains have been stopped.

Salvage excavations have, however, been undertaken at the foot of the tell on both the northern and southern sides. On the northern side, Ruth Amiran of the Israel Museum is digging up a city of the Early Bronze Age II (29th–27th centuries B.C.) similar to the city at Tel Arad which she has excavated for so many years. On the south, excavation of a large Roman-Byzantine city covering scores of acres has begun under the direction of Mordechai Gichon of Tel Aviv University. This Roman-Byzantine settlement seems to have been an unfortified suburb where the militia serving in the fort on top of the tell lived—and even engaged in agriculture in spare time.

Malhata has the longest historical continuity of any of the Negev settlements. We hope to gain enough information from our salvage excavations here to answer at least some of the questions about its history, it relationship to the other sites of the Beersheva valley, and its Biblical identification.

027

Like Malhata, Tel Masos too boasts a long history in the Beersheva valley. Not only does it look different from the other two sites, but we also know much more about it, thanks to three seasons of excavation there a few years ago by a joint German-Israeli team.

Instead of a central tell like Malhata’s, growing higher and higher as time went by, Masos is a collection of separate settlements along the banks of the Nahal Beersheva. Apparently, the settlers of the various periods chose to live in different locales along the river—but always within easy walking distance of the wells in the area.

The previous expedition to the site found remains from the Middle Bronze Age (23rd–16th centuries B.C.), a very large village covering some 12 acres from the early Israelite period (13th–10th centuries B.C.), a fort from the period of the late monarchy, and a monastery from the seventh century A.D. Aharon Kempinski, one of the directors of the earlier expedition, renewed excavations here just months ago with the help of local high school students.

The layout of the huge Israelite village is beginning to emerge, showing a row of attached houses forming a protective belt around its perimeter. Canaanite and Egyptian influences are evident in its public buildings, while many of the imported objects came from places as far away as Midian in the south and the Phoenician coast in the north. The four-room house, the typical Israelite dwelling since the beginning of their settlement period, is the most common type of house plan at Tel Masos.

The identification of Masos, like that of Malhata, is still controversial. The excavations argue that this was the location of Hormah, and that it later became one of the cities of Simeon. I have recently proposed identifying it with the “city of Amalek” conquered by King Saul (1 Samuel 15). In either event it is imperative to proceed with the excavation of this large village of the Israelite settlement period lying exposed on the plains without even a city wall to protect it. It is the only one like this in the region.

Unlike low-lying Tel Malhata and Tel Masos on the plain, Tel Ira juts up sharply from the valley’s floor. It is the largest walled settlement of the Biblical Negev, covering almost 18 acres, and it has never been dug.

Two teams began excavating Tel Ira last year. One is a joint effort by Tel Aviv’s Institute of Archaeology and the Department of the Land of Israel Studies of Bar-Ilan University, and the second team has been fielded by Hebrew Union College of Jerusalem. (My own Aphek-Antipatris Expedition also spent part of the summer at Tel Ira; see “A Volunteer in the Negev,” in this issue.)

At Tel Ira we have uncovered a small settlement of the Early Bronze Age II period, but the longest period of habitation of the tell was under the Judean monarchy. It was then that the solid city wall which crowns the top of the hill was constructed. This construction was undoubtedly the work of one of Judah’s stronger kings (Josiah perhaps?), who turned this site into a fortified eagle’s nest dominating the Beersheva valley, guarding the southernmost border of Judah against Edom. The city wall, still bearing traces of plaster, is impressive in its solidity, its watch-towers, and the mammoth stones used in its foundations. The foundation broadens gradually at the base in order to prevent the wall, sitting as it does on the edge of the precipice, from sliding down the almost vertical slope. Even after the fall of the First Temple and the destruction of this Judean city here at the same time Ira continued to be inhabited. It was quite densely populated in the Hellenistic period. By Byzantine times occupation was confined to the eastern end of the tell, where the remains of a large building, surrounded by subsidiary structures, has been found. First Temple tombs have been found at the foot of the tell, the first burial ground from the period to be discovered in the Negev.

As in the case of the other two sites, there is no consensus about Ira’s ancient name. Yohanan Aharoni, who surveyed and published the site in the 1950’s, thought Ira might be Kabzeel, a name which appears at the beginning of the list of Negev cities of Judah in Joshua 15. Anson Rainey has suggested that Tel Ira was the location of Ramat-Negev, mentioned both in the Bible and the Arad archives. Two ostraca from the First Temple period found here during the first month of excavations have raised our hopes that the site itself will yield some evidence of its ancient name.

Several inscriptions have been found in our rescue excavations. One, a seventh-eighth century B.C. ostracon, seems to be a call to muster addressed to particular people; the people to whom it is addressed include the Biblical names Berechyah and Shelemyah. We hope many BAR readers will substitute their own names for the Biblical names and be called to muster to discover and save the Negev’s past!

As work begins on the infrastructure required to relocate the Israeli army’s bases and training facilities from Sinai to the Negev—in accordance with the Middle East peace agreements—Israel’s archaeological institutions have been mobilized to survey and excavate on an emergency basis threatened sites in the area. Beginning February 1, 1979, salvage excavations began on three of the most important sites in the Negev—Tel Malhata, Tel Masos and Tel Ira. All three are known to have been occupied for long periods in antiquity and lie within the area destined to become the northern airfield of the Negev. The report which […]

You have already read your free article for this month. Please join the BAS Library or become an All Access member of BAS to gain full access to this article and so much more.

Already a library member? Log in here.

Institution user? Log in with your IP address or Username