Return to Aphek

052

053

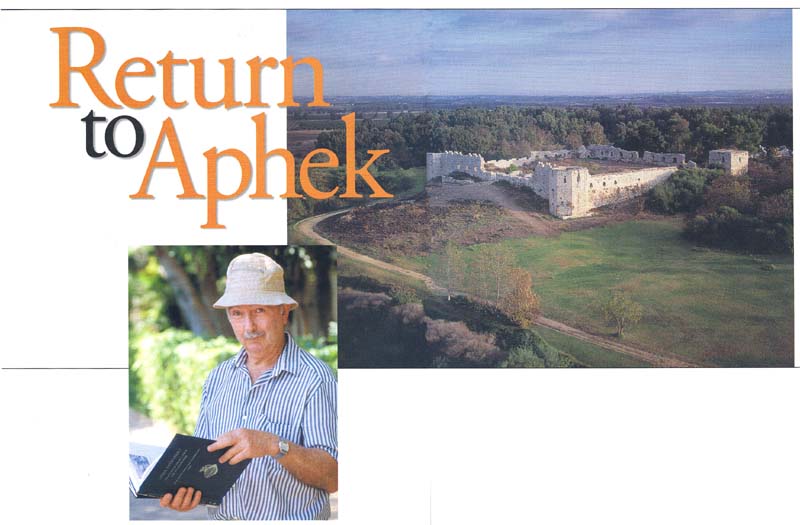

“You can count the centuries as we go down the stairs. We’re going from the 16th century A.D. to the 13th century B.C.,” says excavator Moshe Kochavi as he leads me to some steps inside the remains of ancient Aphek, about 9 miles northeast of Tel Aviv.

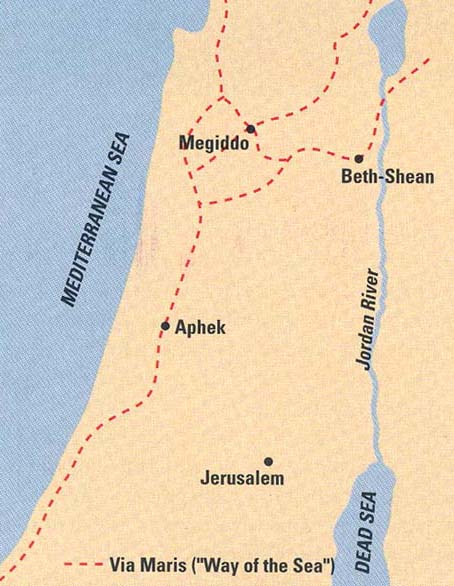

Today a 16th-century Turkish fort, nearly a thousand-feet square, dominates the site; in ancient times Aphek sat astride a key trade route (the Via Maris, the “Way of the Sea,” which ran along the Mediterranean coast). The site protected an important source of water and gets its name from the Hebrew word aphik, riverbed. It is home to the headwaters of the Yarkon River, which flows from here to Tel Aviv and the Mediterranean Sea. In years past a small lake stood just west of Aphek. Because of a long drought in recent years, however, the waters can no longer be seen; they are still present underground, though.

We have come here at my suggestion; I had asked Kochavi to revisit with me one of his past excavations. He selected Aphek, the standout achievement of his long and distinguished career at Tel Aviv University. We are at the site on a typical blistering July day, with the 054Mediterranean sun already a burning ball by mid-morning.

Kochavi is a trim man of slight build with a friendly manner, easily given to wry jokes and a little laugh. He excavated Tel Aphek for 13 seasons, from 1972 to 1985. “The municipality of Petah Tikva decided to build a park next to the site,” Kochavi explains. “They approached our department to conduct the excavation. Yohanan Aharoni, the head of the department, was digging at Beer-Sheva. I was his assistant, and he proposed that I take the project.”

Aphek was the biggest site Kochavi had ever excavated and, at 30 acres, it was one of the largest ancient sites in Israel. But although Aphek covers more area than such major tells as Megiddo and Lachish, it does not dominate the surrounding landscape the way those two imposing sites do because it does not rise nearly as high.

The Bible mentions Aphek several times. Joshua 12:18 lists the king of Aphek as one of the local monarchs defeated by the Israelites in their conquest of Canaan. When the Israelites mounted an attack on the Philistines from Ebenezer (modern Izbet Sartah, another site excavated by Kochavi),a the Philistines encamped at Aphek (1 Samuel 4:1). The Philistines later 055attacked the Israelites at Jezreel from their base at Aphek (1 Samuel 29:1).

Kochavi recounts the history of Aphek as he leads me around the tell. We head first to the northwest corner of the fort, which contains some of the earliest remains. The excavations revealed a city continuously inhabited from the Chalcolithic (4500–3250 B.C.) to the Ottoman (1516–1917 A.D.) period. Large-scale habitation at the site began in the Early Bronze Age (3250–2250 B.C.). Kochavi and his team uncovered residential buildings, a large building with rounded corners, and a city wall made of three courses of fieldstones topped by mudbricks. Even at this early date, the entire tell was occupied. (Soundings were taken throughout the tell.) By Early Bronze Age II (3000–2700 B.C.), the site featured several broad houses arrayed on both sides of two streets. But by Early Bronze Age III (2700–2250 B.C.) the site went into a decline, as shown by a dearth of pottery sherds from that period, and by Early Bronze Age IV (2250–2000 B.C.) Aphek was completely deserted.

The beginning of the Middle Bronze Age (2000–1500 B.C.) saw Aphek reborn as an important city once again. The excavators were able to distinguish six distinct phases of occupation. As in the earlier period, the entire tell was settled. The excavators uncovered homes, tombs and a new city wall, more than 11 feet wide, built slightly uphill from the earlier wall. Smaller finds included storage jars with bichrome (two-color) paint, incised decoration or applied relief. Aphek’s Middle Bronze Age inhabitants also erected, in succession, three palaces at the site. The first and third were built on Aphek’s acropolis, the city’s highest point, on the tell’s northwest corner. Palace II sat somewhat lower on the western slope; Kochavi leads me to it through the gate of the Turkish fort. Palace III, back inside the fort, was the largest of Aphek’s impressive buildings. It boasted walls 7 feet thick and foundations 7 feet deep; it enclosed an area of 43,000 feet and had a 1,600-square-foot reception hall. A huge fire, caused by invading Egyptians, destroyed Palace III at the end of the Middle Bronze Age (about 1550 B.C.).

Aphek enjoyed a renaissance during the Late Bronze Age (1550–1200 B.C.). The period saw the building of three more palaces—in the 15th, 14th and 13th centuries B.C. The last of these, a two-story structure, was the most significant; it was home to Egypt’s local ruler, and Kochavi dubbed it the Egyptian Governor’s Residence. It was built of solid stone walls 5 feet thick and measured 3,600 square feet. A trough stood at the entrance for watering horses.

Kochavi is clearly happy to be leading me around the governor’s house. He takes me through every room, pointing out the courses of walls that still stand as they were found and those courses that his excavation reconstructed from fallen blocks (a thick gray line separates the two). The ground floor of the governor’s house consisted of two small rooms, two storage halls, a corridor and a stone and brick staircase to the second floor. The upstairs contained the living quarters and the area for receiving visitors, Kochavi explains. The layout of the second floor is not known because a fire destroyed it (it is not known who started the fire was started). But the fire did have the fortunate effect (from the archaeologists’ point of view) of sealing the debris from the upper story within the ground floor.

Kochavi remarks on this irony. He mentions something he heard from his teacher, the distinguished excavator and historian, Michael 056Avi-Yonah, back when Kochavi was just beginning his studies in the mid-1950s. “Avi-Yonah said, ‘Archaeologists are sadists. We love earthquakes and conflagrations,’” Kochavi recalls.

The Egyptian governor’s house yielded several cuneiform tablets in Akkadian (the diplomatic lingua franca of the time), including one complete tablet in which Takuhlinu, an official in Ugarit, on the Mediterranean coast of modern Syria, requests that Haya, the governor at Aphek and the top Egyptian officer in Canaan, send him grain. The identities of the two officials, who are also known from other historical sources, allowed Kochavi’s team to pinpoint the date of the Late Bronze Age destruction of Aphek to about 1240 B.C.

The discovery of the letter from Ugarit, Kochavi says, was not only an important archaeological find but was important for the excavation as well. “We really came on the map when we found it.”

After the 1240 B.C. destruction, Aphek was largely abandoned for about a century. The twelfth century B.C. saw the building of two 057residential areas; one contained well-built, square structures with paved courtyards and a poorer section with more slapdash buildings. In this poorer area Kochavi found fishhooks, net weights and turtle shells—clear indications that the area was home to fishermen.

The Philistines arrived at Aphek in the 11th century B.C. Among the artifacts they left behind were several figurine heads of Ashdoda (a Philistine goddess), a clay tablet inscribed in an undeciphered script (scholars have yet to crack the Philistine language) and Philistine-style pottery. But Aphek was also something of a cultural crossroads. Kochavi found tenth-century B.C. stone-lined silos—which appear at many Israelite sites—built into the debris of Aphek’s 11th or 12th-century B.C. strata. By the tenth century B.C., the Israelite presence at Aphek is unmistakable; in addition to the silos, a totally different layout of the site indicates the presence of new inhabitants.

Aphek reached its most elaborate incarnation from the time of Herod (ruled 37–4 B.C.) on. As Rome’s client king in Judea, Herod assembled a matchless record as builder of cities, palaces and sumptuous buildings. Herod rebuilt Aphek and named it Antipatris, after his father Antipater. Josephus, the first-century A.D. historian, records that Herod picked the most lush area in the region for the commemoration of his father.

To see the Roman-era remains, Kochavi leads me south of the Turkish fort. A sign greets us: “Danger, No Passage.” Kochavi gives a little laugh; pointing to the sign, he says, “This almost invites us to pass through.” We skip past the sign.

We stand on the remains of the Cardo, the main street, which was 30 feet wide and had shops on both sides. In the Roman and Byzantine periods (first-fourth centuries A.D.), the city also boasted mansions with elaborate mosaic floors, a forum surrounded by public buildings and an Odeon (a small theater). A powerful earthquake in 363 A.D., which caused widespread havoc throughout ancient Israel, destroyed Aphek/Antipatris. No town was ever built on the tell again, though the Ottoman Turks erected their fort in 1572 A.D. as a cavalry base to guard the important road that passed nearby. In keeping with the site’s longstanding association with water, they named the fort Binar Bashi, meaning “Head of the Spring.”

After our tour Kochavi invites me back to his apartment, in a shaded, tree-lined neighborhood near the Tel Aviv University campus. He is delighted to see that his daughter Tal has 058come to visit with his grandson. It is Friday afternoon, and even in secular Tel Aviv people are beginning to slow down for the Jewish Sabbath. Kochavi’s daughter offers us a pitcher of freshly brewed iced tea, and Kochavi reminisces a bit about his career.

Kochavi’s first excavation was at Har Yerucham, 25 miles south of Beer-Sheva, as part of his dissertation on the Middle Bronze Age in the Negev. In the 1960s he was a field director at Tel Zeror, about 20 miles south of Haifa, for a Japanese team—his first experience at a multi-period site. After the Six-Day War of 1967, Kochavi directed the surface survey of Judea. He is currently involved in the Land of Geshur Project, a multi-site excavation in the Golan. Working with him there are some Japanese students who are the students of the people he worked with at Tel Zeror. In the summer of 2002, Kochavi planned to be in the field at Ein Gev, along the eastern coast of the Sea of Galilee. Despite the violence in Israel and the West Bank, a group was scheduled to come over from Japan—one of the very few foreign groups to dig in Israel this season.

Of all the sites he has excavated, Aphek is clearly the one Kochavi considers the most significant. He proudly displays the first volume of the Aphek final report and says that the next volume will be out in a year or two. He also recalls some of his colleagues and students who worked with him at Aphek: his late colleague, Pirhiya Beck; David Owen, of Cornell University, who deciphered the letter from Ugarit; George Kelm, of New Orleans Baptist Seminary; Bruce Cresson, of Baylor University; Israel Finkelstein, who co-directs the Megiddo excavation and who now heads Tel Aviv University’s Institute of Archaeology;b and Shlomo Bunimovitz and Zvi Lederman, who co-direct the dig at Beth-Shemesh.c

Kochavi makes one last point about the Aphek excavation. Yohanan Aharoni had advised him to begin his dig at the very top of the tell 059because that’s where the most significant finds would be. But Kochavi feared that he would have to spend years digging away later material at the top before getting to earlier material, so he began his dig further down the slope, outside the Turkish gate. Only later did he dig on the acropolis, where he immediately found early remains. What he hadn’t realized was that the Turks had leveled the acropolis in order to build their fort and had thus removed the topmost layers. “Aharoni was right,” Kochavi tells me, “the most important material is at the top of a tell.”

It has been a long day of learning with a veteran excavator, but it is time to go. I finish the last of my iced tea. Only later do I realize that the water in the glass, like Professor Kochavi and I, had recently come from Aphek.

“You can count the centuries as we go down the stairs. We’re going from the 16th century A.D. to the 13th century B.C.,” says excavator Moshe Kochavi as he leads me to some steps inside the remains of ancient Aphek, about 9 miles northeast of Tel Aviv. Today a 16th-century Turkish fort, nearly a thousand-feet square, dominates the site; in ancient times Aphek sat astride a key trade route (the Via Maris, the “Way of the Sea,” which ran along the Mediterranean coast). The site protected an important source of water and gets its name from the Hebrew […]

You have already read your free article for this month. Please join the BAS Library or become an All Access member of BAS to gain full access to this article and so much more.

Already a library member? Log in here.

Institution user? Log in with your IP address or Username

Footnotes

See Hershel Shanks, “After Excavation: What Happens When the Archaeologists Leave?” BAR 28:03.

See Israel Finkelstein and David Ussishkin, “Back to Megiddo,” BAR 20:01.

See Shlomo Bunimovitz and Zvi Lederman, “Beth Shemesh: Culture Conflict on Judah’s Frontier,” BAR 23:01.