034

The first Judahite royal palace ever exposed in an archaeological excavation is bei ng rediscovered. And with this renewed interest come echoes of what is probably one of the bitterest rivalries in the history of Israeli ar chaeology—between Israel’s most illustrious archaeologist, Yigael Yadin of Hebrew University, and his younger colleague Yohanan Aharoni, who bo lted and formed the Institute of Archaeology at Tel Aviv University. Ramat Raḥel sits on a mountaintop halfway between ancient Jerusalem and Bethlehem, about 3 miles from each. From the summit, 2,600 feet above sea level, a magnificent landscape unfolds: To the north the visitor sees ancient Jerusalem—the Mount of Olives and the Temple Mount, with its gold- covered Dome of the Rock—and large segments of the bustling new city. To the south, beyond the Greek Orthodox monastery of Mar Elias, lies Bethlehem, with the Church of 036the Nativity and Manger Square. Farther south you will see the northernmost part of the Hebron hills and to the southeast, parts of the Judean Desert. Herodium, the volcano-shaped mountain with the palace-fortress of Herod the Great, appears on the horizon. Eastward on a clear day in winter, beyond the barren hills of the Judean Desert, the bluish mountains of Moab in Trans-Jordan rise like an apparition. Westward, Jerusalem’s new suburbs fill the landscape on either side of the Refaim Valley, which connects the Judean hills with the Mediterranean coastal plain.

Ancient remains at Ramat Raḥel were first noted by 19th-century pioneers of Holy Land archaeology such as the German missionary and explorer Conrad Schick and the French diplomat and scholar Charles Clermont-Ganneau.1 The first excavations were conducted in 1930 and 1931 by Benjamin Maisler (later Hebraicized to Mazar) and Moshe Stekelis, both of whom became professors in the fledgling archaeology department of the Hebrew University in Jerusalem. Among their finds from the First Temple period (eighth–sixth centuries B.C.E.) was a carved frieze decorated with small columns with elegant capitals and a royal seal impression of a type that will figure importantly later in this article. Maisler also noted remains of a city wall that had enclosed the site.2

In 1954 the kibbutz of Ramat Raḥel wanted to erect a water tower on the summit of the site. Before construction could begin, however, a salvage dig was required to assess the archaeological remains on the proposed site and to determine 037whether the construction could proceed. (Construction was ultimately approved, and the water tower is still there.) The excavation was headed by Yohanan Aharoni, who was then an employee of the governmental department of antiquities. In addition to impressive architecture, he found a rich collection of stamped jar handles from the time of the Judahite monarchy to be added to the single similar impression Maisler had found.3

Aharoni returned to the site for four seasons between 1959 and 1962 under the auspices of the Hebrew University and the University of Rome, during which he uncovered more of this impressive building that could now be identified as a palace. Unfortunately, the results were published only in preliminary fashion, without detailed plans or section drawings.4 Aharoni died unexpectedly in 1976 at 57 years of age. He dated the Ramat Raḥel palace to about 600 B.C.E.—to the reign of King Jehoiakim, just a few years before the Babylonian destruction of Jerusalem in 587/586 B.C.E. However, Aharoni perspicaciously predicted the existence of an earlier stratum of the palace dating to the late eighth century B.C.E. (the reign of King Hezekiah). Although Aharoni never found clear evidence of this earlier stratum under the later Iron Age remains, he nevertheless proposed it because of the rich ceramic assemblages in the fills under the floors of the palace that he did find. He assumed that before the construction of the palace an earlier phase left the remains that became fill beneath the later palace. The earlier phase came to an end, most probably, with Sennacherib’s assault on Hezekiah’s Jerusalem in 701 B.C.E. That was the culmination of Sennacherib’s campaign to Judah. Although Sennacherib was unsuccessful in his siege of Jerusalem, an independent, first-person account of the campaign in Sennacherib’s own words survives in which he boasts that he destroyed 46 unnamed cities in Judah; Ramat Raḥel was one of them.

Yadin was delighted to disagree with Aharoni’s dating. Yadin pointed to marked architectural similarities of the Ramat Raḥel palace in both plan and decoration to the royal palace at Samaria, capital of the northern kingdom of Israel. (The United Monarchy split after Solomon’s death in about 930 B.C.E. into the northern kingdom of Israel and the southern kingdom of Judah.) Yadin suggested that the palace of Ramat Raḥel dated to the reign of Queen Athaliah (842–836 B.C.E.).5 This would account for the architectural similarities to Samaria because Athaliah had been a princess of the house of Omri, the royal family of the northern kingdom of Israel, when she would have lived in the capital at Samaria. For Yadin, the Ramat Raḥel palace was the “House of Baal,” which the Bible tells us Queen Athaliah built (2 Kings 11:18).

On the other hand, Aharoni drew support for his dating of the existing palace to Jehoiakim (609–598 B.C.E.) (after the assumed earlier palace from the eighth–seventh centuries B.C.E. had been destroyed) from both archaeology and from the Bible. First, Aharoni had found a seal impression inscribed “(belonging) to Elyakim steward of Yukin.” Other examples of impressions of this same seal had been found by the eminent William F. Albright at Tell Beit Mirsim from 1926 to 1932 and also in the excavations at Beth-Shemesh. Albright identified “Yukin” as Jehoiachin. That is, our Elyakim was a minister of King Jehoiachin. Later it was discovered that the seal impressions of “Yukin” were part of a group stamped upon royal jars dating to the eighth century B.C.E. and not to the sixth century B.C.E. On the Biblical side, Aharoni pointed to the book of Jeremiah: “Woe to him who builds his house by unrighteousness and his upper rooms by injustice … who says I will build myself a great house with 038spacious upper rooms and cut out windows for it, paneling it with cedar and painting it with vermilion” (Jeremiah 22:13–14). Aharoni proposed that this Biblical text was referring to the evocative window balustrades he had found and which we will discuss later in detail.

So the same palace was dated by the excavator, Yohanan Aharoni, to about 600 B.C.E. while the interloper Yigael Yadin (who died in 1984) dated the same building about 250 years earlier.

In hopes of resolving this conflict, I led an expedition to the site in 1984.6 To reveal the end at the beginning, both antagonists were right and both were wrong.

First of all, we discovered that the site was larger than Aharoni had supposed. Ramat Raḥel was not simply a palace compound, but a small city covering an area of more than 30 dunams (about 7.5 acres). The city was enclosed by a so-called offset-inset wall of unworked field stones. The wall is about 13.5 feet thick, which equals 8 royal Egyptian cubits.

In one small area in the internal palace courtyard we established the existence of two clearly superimposed Iron Age levels, just as Aharoni had supposed. In this respect, he was right—there was an earlier stratum even though he did not find it underneath the later palace structure.

Aharoni was also right that the earlier (but undiscovered) stratum was most probably a palace built by Hezekiah and probably destroyed by Sennacherib on his campaign to Judah in 701 B.C.E.

But Aharoni was wrong in concluding that the later stratum, which he did find, and the palace that survived in the archaeological record, was built by Jehoiakim in about 600 B.C.E. Soon after it was destroyed, the palace Hezekiah built was reconstructed—either late in Hezekiah’s reign or in the reign of his son and successor Manasseh. So Aharoni was wrong in his dating of the palace he excavated.

039

Turning to Yadin, he was wrong in dating the excavated palace to the mid-ninth century. But he was right in noting the similarities to the architectural plan and details of buildings in the capital of the northern kingdom of Israel—Samaria. This similarity is due, however, not to the influence of Athaliah’s connection to her birthplace in Samaria, but to the many architects and artisans from Israel who fled to Judah in the aftermath of the Assyrian invasion of 722 B.C.E. that ended with the demise of the northern kingdom.

Although the date of the Ramat Raḥel palace has been a matter of controversy, and even acrimony, there has been no doubt that it is a palace. That is clear from its location within the city, from its plan and construction and from the finds within it that are both dramatic and revealing.

The palace sits in the center of the city on the peak of the tell. The entire palace complex is enclosed by a casemate wall; that is, a double wall with intermittent cross-walls creating casemate chambers within the wall. The entrance to the palace complex was on the east, probably opposite a gate in the eastern city wall. The casemates that enclosed the palace complex could be entered from inside the palace complex. Some of the casemates were connected with one another. These chambers probably served for storage and as living quarters for the palace guard.

In front of the palace complex, to the east, was a forecourt paved with crushed lime. Within the casemate enclosure of the palace was another large inner court, also paved with crushed lime. The palace, as mentioned, was entered from the east; the ancient Israelites in most cases preferred to orient their public and private buildings in this direction. The Temple in Jerusalem, for example, was also entered from the east.

The palace itself is rectangular and appears to have been designed using the standard long or royal Egyptian cubit, which is approximately 1.7 feet. By this measure, the building measures 100 by 150 cubits (164 x 256 feet).7 Other elements of the palace complex also appear to have been constructed using the royal Egyptian cubit. For example, each casemate in the wall around the complex was approximately 10 cubits long by 5 cubits wide. The outer wall of the (double) casemate wall was 3 cubits thick, while the inner wall was 2 cubits thick.

Once inside the palace, the visitor would find himself in the central courtyard paved with whitish crushed lime. This internal courtyard measured 60 by 50 royal Egyptian cubits. From here the visitor could enter the rooms of the palace. Enough has been excavated to determine that there was a residential wing on the west and an administrative and service wing on the north. The residential wing opened onto a view of the valley of Refaim. Here the occupants could enjoy a cool breeze even in summer.

The superb quality of the masonry and the architectural details of the palace make it the finest First Temple period building ever excavated in Judah. The ashlars (shaped rectangular stones) are so masterfully cut that mortar was not needed. The blade of a knife will not fit between the beautifully squared ashlars to this day, as the stones are so perfectly fitted together. After cutting, the exposed surface of the quarried ashlars was smoothed with an iron instrument that eliminated the chisel marks made during quarrying. The Hebrew word for this process and the instrument used to smooth the stones is megerah (plural, megerot). The Bible describes “costly stones … sawed (megorarot) with saws (megerah)” (1 Kings 7:9). The term “sawed” is a mistranslation, however. The text actually refers to the smoothing process and the instrument used to smooth the stones.

Unfortunately, the remains of the palace are extremely scant, often barely protruding above bedrock. The fine masonry was robbed in later 040periods for secondary use in other buildings because of its high quality.

Aharoni also found ten finely crafted Proto-Ionic capitals (also called Proto-Aeolic) in the palace, each featuring a central triangle with the point at the top flanked by palmettes on either side.8 Some of the capitals are carved in relief on front and back, while others are carved on only one side. The two-sided capitals were used on free-standing columns; those carved only on one side probably faced the internal courtyard, where seven of the ten capitals were found. The ones carved on only one side probably topped engaged pillars attached to walls, so that only one side of the capital was visible.

Another difference between the capitals involves their width. Some are 43 inches wide and others only 31 inches wide. The supposition is that the larger ones were used on bigger columns or pillars. The narrower ones—for smaller columns or pillars—may have been used on an upper floor.

Proto-Ionic capitals are surely one of the most beautiful features in the royal architecture of the kingdoms of Judah and Israel. They have been dated from the tenth century to the eighth century B.C.E. at such sites as Megiddo, Tel Dan, Hazor, Samaria, Jerusalem and at Madeibi‘a in ancient Moab (modern Jordan). Those from Ramat Raḥel represent the most elegant and most developed 041type found in the Land of Israel. Thus they seem to be later than their northern Israelite predecessors found at Megiddo, Tel Dan, Hazor and Samaria.

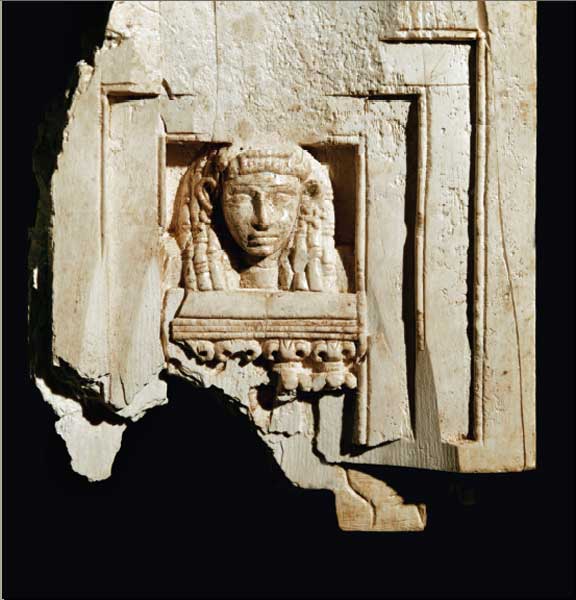

One of the more intriguing finds at Ramat Raḥel was a series of window balustrades carved in limestone and consisting of a series of small columns about 9 inches high, each topped with a small three-dimensionally carved capital echoing elements of the large Proto-Ionic capitals found elsewhere in the palace. The capitals on the small columns are joined to one another. Each capital has two palmettes flanking an egg-shaped pattern in the center. The capitals were attached to the columns by metal fittings. Each of the columns also had a hole carved at mid-height through which a wooden stick could be passed to join the columns together. The tops of the capitals have holes for attaching a railing or windowsill. Some of the balustrade fragments bore traces of red paint. A restored window balustrade from Ramat Raḥel is on display at the Israel Museum in Jerusalem and is also pictured on a modern Israeli postage stamp.

The palace probably had several windows, perhaps on an upper story, in which these balustrades were used. Similar window-balustrade fragments were also found in excavations led by Yigal Shiloh in the City of David in Jerusalem.9 Did the palace of Ramat Raḥel draw its inspiration from the elaborate palaces at nearby Jerusalem, the kingdom’s capital?

Aharoni also found a small limestone stepped-pyramid-shaped stone with three steps on each side—probably part of the crenellation that topped the palace wall. Similar crenellation stones have been found at other sites in Israel—Samaria, Megiddo, Tel Mevorakh (north of Caesarea)—and 042also in the palace of Sargon (late eighth century B.C.E.), king of Assyria.10

Perhaps the most explanatory, if not the most important, finds at Ramat Raḥel were 164 jar handles stamped with the word lmlk—“(belonging) to the king.” These seal impressions are exceedingly well-known in the archaeology of ancient Judah. They were impressed into the handles of large storage jars. For a long time their date was a matter of fierce dispute. Did the two-winged types with a sun disk in the center date from a different period than the ones with a four-winged beetle? Now, as a result of the excavations at Lachish led by Tel Aviv University archaeologist David Ussishkin, the dating of these l’melekh handles is settled; at Lachish more than 10 complete jars with both types of seals and more than 400 such stamped handles were found in a clearly dated stratum (the famous Stratum III) that was destroyed by Sennacherib in 701 B.C.E.11 Hence the approximately 2,000 l’melekh handles that have been found in Judah all date to the reign of King Hezekiah in the late eighth century B.C.E. The l’melekh handles found at Ramat Raḥel are a major assist in dating the palace.

The inscriptions on l’melekh handles, always include, in addition to “(belonging) to the king,” the name of one of four cities: Hebron, Sokoh, Ziph and mmt. The first three cities are well known from the Bible, but the fourth name is unknown in either the Bible or in extrabiblical sources. It appears only on these seal impressions. We’re not even sure how to pronounce it, as it is written without vowels.

Scholars are generally agreed that these four cities on the royal seal impressions refer to some kind of administrative centers in the kingdom of Judah under King Hezekiah. Hebron represents the southern Judean Hills; Sokoh, the areas of the Shephelah (the Judean foothills); and Ziph, the fringe areas (the wilderness in the southern and eastern parts of the kingdom). But what of mmt? It stands to reason that it represents the area of the northern Judean Hills, around the capital, Jerusalem.

Ramat Raḥel (Rachel’s Height) was named by the kibbutz of the same name after the Biblical matriarch Rachel, who died in childbirth and was buried, according to tradition, not far to the south on the road to Bethlehem: “So Rachel died, and she was buried on the way to Ephrat (that is, Bethlehem)” (Genesis 35:19). The kibbutz was established in 1926, and the ancient ruin within its premises was called Khirbet es-

If we reject these suggestions, what then is the ancient name of Ramat Raḥel? I believe it is the until-now unidentified mmt, the fourth city found on the l’melekh handles. Mmt must be a city comparable in size and importance to the other three cities on the l’melekh handles. It must have been occupied during the reign of Hezekiah. And we should look for it in the northern part of Judah, somewhere around Jerusalem.

It would seem that Ramat Raḥel is the ideal candidate. Moreover, about 170 l’melekh handles have been found at Ramat Raḥel. This is more than have been found at any other site in Judah, except Lachish and Jerusalem.

If anyone can find a better candidate for mmt, I challenge him to make his case.

The identification of another artifact found at Ramat Raḥel—a pottery sherd with a painted picture on it—may be the only portrait ever discovered of a king of Judah. The 5-by-3-inch sherd discovered in the palace indistinctly depicts, in black and red, a royal figure with a beard that juts forward. He may have worn a tiara crown as do contemporaneous Assyrian monarchs, but the sherd does not include the top of the figure’s head, so we cannot be sure. He sits on a throne with his hands stretched forward. The painting stresses the subject’s facial features, the garment with woven or embroidered stripes, and bracelets on the wrist and upper arm. The thickening at the center of the wrist bracelet was probably a royal rosette. The artist clearly drew the muscles of both arms, as well as some details of the throne. Unfortunately, the painting is even more indistinct today than when it was found.

The famous Italian archaeologist Paolo Matthiae, widely known for his excavation of the site of Ebla in Syria where thousands of cuneiform tablets were found, also dug in Israel. Matthiae excavated at Ramat Raḥel with Aharoni and studied the sherd. Matthiae was “certain” that the portrait on the sherd represented a Judahite king.12 I believe Matthiae was right.

The seated figure, according to Matthiae, was first outlined in a fine black line. Next a broader band of red paint was applied. The general style of the 044painted figure is reminiscent of figures in Assyrian art, especially in the wall paintings of Tiglath-pileser III, king of Assyria (745–727 B.C.E.), at Arslan-Tash in northern Syria. But certain details, like the jutting beard, do not quite fit the Assyrian model.13

It clearly represents a royal figure seated on a throne. Based on the find spot and the fact that it is painted on a locally made potsherd, I believe it is likely a portrait of Hezekiah, the king who built Ramat Raḥel and its palace.

Although Ramat Raḥel was destroyed in the late eighth century B.C.E., most probably by Sennacherib, it appears to have been rebuilt shortly after Sennacherib abandoned his siege of Jerusalem, most likely by Hezekiah himself in the later years of his reign, although his son Manasseh is another candidate. Manasseh reigned from 698 to 642 B.C.E., when the kingdom of Judah flourished.

Ramat Raḥel and its palace finally succumbed in 587/586 B.C.E. to Nebuchadnezzar, king of Babylon, who destroyed Jerusalem and the Temple and exiled the people, thus ending the 400-year history of the Davidic dynasty. Ramat Raḥel continued, however. Remains have been found from the Babylonian, Persian, Hellenistic, early Roman and late Roman periods (sixth century B.C.E.–third century C.E.). These include remains of structures, several mikveh installations (Jewish ritual baths), burial caves and pottery. In the Byzantine period (fourth to seventh centuries C.E.) the site was a Christian settlement with a church and a monastery. This settlement continued into the early Islamic period (seventh–eighth century C.E.), when the long history of ancient Ramat Raḥel finally came to an end.

The first Judahite royal palace ever exposed in an archaeological excavation is bei ng rediscovered. And with this renewed interest come echoes of what is probably one of the bitterest rivalries in the history of Israeli ar chaeology—between Israel’s most illustrious archaeologist, Yigael Yadin of Hebrew University, and his younger colleague Yohanan Aharoni, who bo lted and formed the Institute of Archaeology at Tel Aviv University. Ramat Raḥel sits on a mountaintop halfway between ancient Jerusalem and Bethlehem, about 3 miles from each. From the summit, 2,600 feet above sea level, a magnificent landscape unfolds: To the north the […]

You have already read your free article for this month. Please join the BAS Library or become an All Access member of BAS to gain full access to this article and so much more.

Already a library member? Log in here.

Institution user? Log in with your IP address or Username

Endnotes

Conrad Schick, “Mitteilungen aus Jerusalem,” Zeitschrift des Deutschen Palastina Verein (ZDPV) I (1878), pp. 13–15; Charles Clermont-Ganneau, Archaeological Researches in Palestine, vol. 1 (London, 1899), p. 457.

Benjamin Maisler, “Ramat Rachel and Khirbet Salih.,” Journal of the Jewish Palestine Exploration Society (Jerusalem, 1934–1935), pp. 4–13 (Hebrew).

Yohanan Aharoni, “Excavations at Ramath Raḥel 1954, Preliminary Report,” Israel Exploration Journal 6 (1956), pp. 102–111, 137–157.

Yohanan Aharoni, Excavations at Ramath Raḥel, Seasons 1959 and 1960 (Rome: Centro di Studi Semitici, 1962); Excavations at Ramath Raḥel, Seasons 1961 and 1962 (Rome: Centro di Studi Semitici, 1964).

Yigael Yadin, “The ‘House of Ba‘al’ of Ahab and Jezebel in Samaria, and that of Athalia in Judah,” in P.R.S. Moorey and Peter Parr, eds., Archaeology in the Levant, Essays for Kathleen Kenyon (Warminster, England: 1978), pp. 127–135.

The dig of June to August 1984 (license number 1319/84) was carried out under the auspices of Tel Aviv University and the Israel Exploration Society.

On the subject of the ancient cubit standard in Judah, see Gabriel Barkay, “Measurements in the Bible—Evidence at St. Etienne for the Length of the Cubit and the Reed,” BAR 12:02.

See Yigal Shiloh, “The Proto-Aeolic Capital and Israelite Ashlar Masonry,” Qedem (Monographs of the Institute of Archaeology), (Jerusalem: Hebrew University), vol. 11, 1979.

See, for example, John Winter Crowfoot, Kathleen M. Kenyon and Eliezer L. Sukenik, “The Buildings at Samaria” (London, 1942), pl. LX:1, Robert S. Lamon and Geoffrey M. Shipton, Megiddo I (Chicago, 1939), fig 36, p. 28.

David Ussishkin, “The Destruction of Lachish by Sennacherib and the Dating of the Royal Judean Storage Jars,” Tel Aviv 4 (1977), pp. 28–60; Gabriel Barkay and Andrew G. Vaughn, “The Royal and Official Seal Impressions from Lachish,” in Ussishkin, ed., The Renewed Archaeological Excavations at Lachish 1973–1994, vol. 4 (Tel Aviv, 2004), pp. 2148–2173.

Paolo Matthiae, “The Painted Sherd of Ramat Raḥel,” in Aharoni, Excavations at Ramat Raḥel (Seasons 1961 and 1962), pp. 85–94.