Herculaneum and Pompeii were both destroyed by the same eruption of Mount Vesuvius in 79 A.D. For archaeologists, however, it must seem that they were leveled by different volcanoes entirely.

Pompeii was smothered beneath a shallow blanket of volcanic pebbles (lapillae) and dust. It has been relatively easy to excavate, and today two-thirds of the ancient city is visible to modern visitors.

Herculaneum, on the other hand, was buried alive. The full force of the volcano struck the site in 12 avalanche-like surges of mud and detritus, which shoved the sea itself forward by several hundred yards. Eruptions in later centuries buried the city even deeper, and the thick crust solidified into rock. Today, Herculaneum and its ancient shoreline lie 70 feet below ground level, the equivalent of a four-story building.

Until Benito Mussolini launched a state-sponsored excavation of Herculaneum, the only structures that had been explored at the site (through underground tunnels) were a Greek theater and a large villa. The villa, now known as the Villa of the Papyri, belonged to Julius Caesar’s father-in-law, Lucius Calpurnius Piso Caesonius, and contained a library of Greek and Latin manuscripts. Apart from these buildings, the seaside resort town of Herculaneum remained a vanished ghost of Vesuvius.

In 1927, as part of his so-called campaign of national pride, Mussolini appointed the archaeologist Amedeo Maiuri to excavate Herculaneum. Most of Maiuri’s finds—along with those of the excavations that followed in later years—were to be housed and exhibited in an on-site museum. The problem, however, is that the museum was never completed and, so far, has been used only for storage and for office space. Important objects excavated at Herculaneum have remained under lock and key in that building, unavailable even to scholars.

Now, the Italian government is completing and renovating the museum, which is scheduled to open in two years. The centerpiece of the museum’s collection is a hundred wooden items preserved at Herculaneum—for the debris that destroyed the city paradoxically preserved wood that otherwise would have rotted away. (The wood in the city’s houses is being restored in situ.) Restoration work on the wood is being funded by the Packard Humanities Institute, an American foundation dedicated to preserving the world’s ancient heritage.

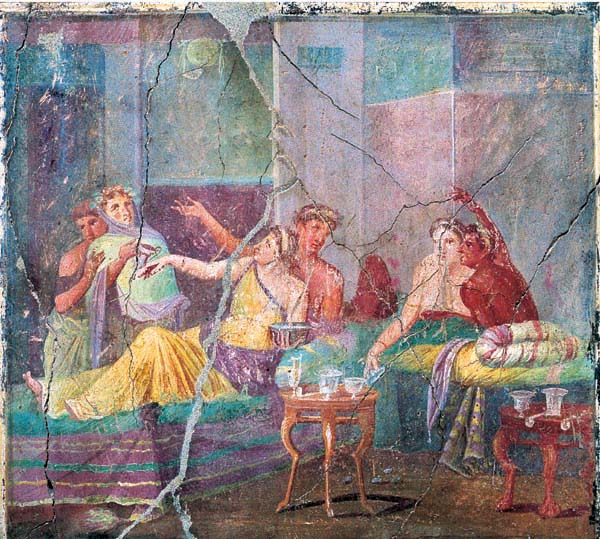

Packard is also bankrolling the restoration of nearly 30 pieces of wooden household furniture found at Pompeii. These items include benches, cabinets, a baby’s cradle, high-backed sofas with three sides, a wooden treasure chest, a stool, farm tools and a small cabinet with a drawer that looks just like a bedside table. Some pieces of furniture have elegant wooden inlays worked into geometric patterns.

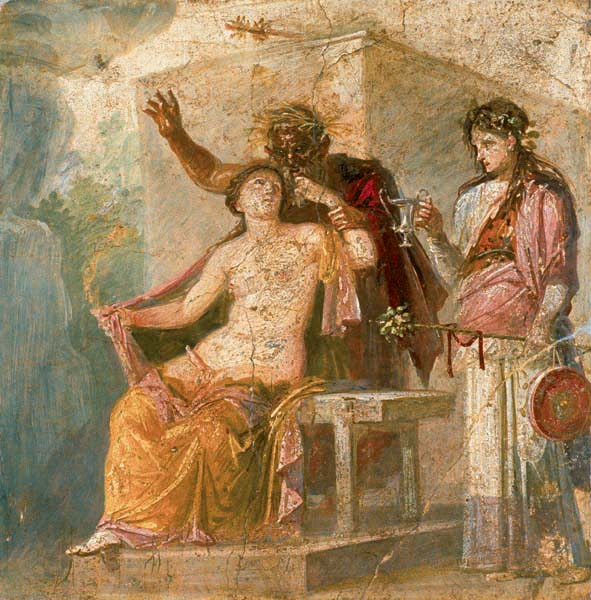

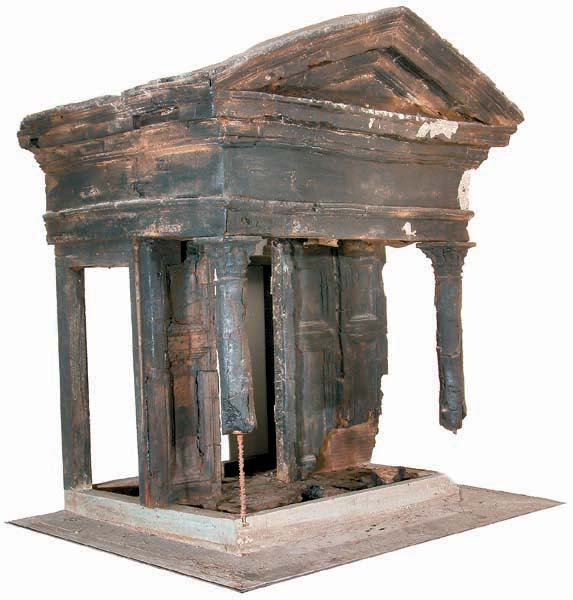

Four of the cabinets were shrines (lararia) housing images of the household gods. Of these, the most impressive lararium had two levels with doors above and below. The top part was a finely worked tabernacle whose two doors were flanked by Corinthian-style columns. This cabinet was found filled with small bronze statues, including one of the god Hercules, the traditional founder of Herculaneum. Several crudely manufactured wooden statues of gods were also found.

At Herculaneum, archaeologists have unearthed several round wooden tables with three legs—very similar to marble and bronze tables also found at Herculaneum and Pompeii. The legs of these tables—marble, bronze and wood—are carved to resemble the profile of a lion or dog.

Utilizing the technology of his day, Amedeo Maiuri preserved wooden furniture by taking apart each object, soaking its separate pieces in a mixture of hot paraffin (blackened so that the wood would not dry white) and then reassembling the whole. In the l980s plexiglas supports were added where pieces were missing.

To begin the new restoration, conservators need to remove the 60-year-old paraffin. They then soak the wood in a blend of resin and natural beeswax. Titanium is among the materials being utilized for support of legs and backs.

The process is far from finished, but one of the conservators, Luigi Sirano, who showed this writer around the workshop and is preparing a detailed description for a catalogue, is optimistic: “We will have finished the restoration by 2006. Then we plan to open the new museum at Herculaneum.”