Searching for the Better Text

How errors crept into the Bible and what can be done to correct them

024025

Isaiah’s vision of universal peace is one of the best-known passages in the Hebrew Bible: “The wolf shall dwell with the lamb, and the leopard shall lie down with the kid; and the calf and the young lion and the fatling together; and a little child shall lead them” (Isaiah 11:6).

But does this beloved image of the Peaceable Kingdom contain a mistranslation?

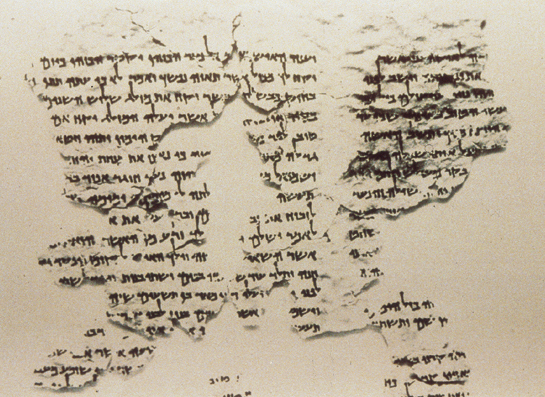

For years many scholars suspected that it did. Given the parallelism of the phrases, one would expect a verb instead of “the fatling.” With the discovery of the Isaiah Scroll among the Dead Sea Scrolls, those scholars were given persuasive new support. The Isaiah Scroll contains a slight change in the Hebrew letters at this point in the text, yielding “will feed”: “the calf and the young lion will feed together.”

This is just one of numerous variations from the traditional text of the Hebrew Bible contained in the Dead Sea Scrolls. In some cases the traditional text is clearly superior, but in others the version in the scrolls is better.

Thanks to the scrolls, more and more textual problems in the Hebrew Bible are being resolved. The notes in newer Bible translations list variant readings from the scrolls, and in some cases, the translations incorporate these readings in the text as the preferred reading. No one has ever seriously suggested that the Dead Sea Scrolls contain anything like an eleventh commandment; but the scrolls do help clarify numerous difficult phrases in the Hebrew Bible, and for textual scholars that is more than enough.

Before we list other examples of how the Dead Sea Scrolls influenced—or altered—Bible translations, we need to understand how ambiguities crept into the text of the Hebrew Bible in the first place. And we must also familiarize ourselves with the ancient versions of the Hebrew Bible on which modern translations rely (for good reason scholars call these ancient versions “witnesses” to the biblical text).

Hebrew is remarkably compact: Almost all words consist of consonantal roots that convey their basic meaning. L-M-D, for example, means “learning,” B-Q-R means “examining,” and K-T-B, “writing.” Particular patterns of vowels and consonants 026narrow the meaning; me-a-e added to a root means “one who,” while a-a means “he did.” Thus, meLaMeD is “one who teaches,” meBaQeR is “one who examines,” LaMaD is “he learned,” and KaTaB is “he wrote.”

These vowels are crucial for the meaning. However, ancient Hebrew writing recorded no vowels, only consonants. (Vowel marks were not added to Hebrew writing until the sixth or seventh century C.E.) Consonants alone were usually enough to distinguish between possible meanings. LMDT means “you (singular) learned,” while LMDTM means “you (plural) learned.” Often, however, the absence of vowels in written Hebrew leads to ambiguity. The word NSTM, which appears in Zechariah 14:5, could be parsed as the root STM with the prefix N, in which case it would mean “(it) was filled up.” But it could just as plausibly be read as NS with the suffix TM, which means “you (plural) fled.” The Jerusalem Bible translation opts for the former reading and translates the passage in Zechariah as “And the Vale of Hinnom will be filled up…it will be blocked as it was by the earthquake in the days of Uzziah king of Judah.” The King James Version, however, reads “And ye shall flee to the valley of the mountains…like as ye fled from before the earthquake in the days of Uzziah king of Judah.” Fleeing citizens in one text, a filled up valley in another. How much difference one word makes!

To eliminate, or at least reduce, such ambiguities, a convention arose among Hebrew scribes. They began to insert certain consonants, to be used as vowels, as aids to reading; these are called matres lectionis, literally, “mothers of reading.” LMD (lamad, “he learned”) became visually distinct from LMDH (lamda, “she learned”) and LMDW (lamdu, “they learned”). Such expanded spellings are called plene, or “full,” orthography (spelling); the more rudimentary spellings are called defectivus, or “defective,” orthography.

Plene orthography did not catch on all at once; some scribes were using full spellings as early the first century B.C.E., while even today in Israel their usage has not been standardized. One Dead Sea Scroll that testifies to the older scribal tradition contains Deuteronomy 24:14. The traditional Hebrew text contains the full spelling SKYR (sakir), meaning “workman”; most translations give “You should not oppress a workman.” But this manuscript, called 1QDeutb, contains the “defective” form SKR (sakar), which can also mean “wages”; following this scroll, the New English Bible renders the passage as “You shall not keep back the wages of a man.”

So far we have discussed “micro” issues—variations in spelling and the like. But there is a much larger factor that contributes to the differences we find in modern Bible translations: the variations in the textual traditions behind the text of the Hebrew Bible.

We have three major traditions, or “witnesses,” to the Hebrew Bible: the Masoretic text, the traditional Jewish text; the Septuagint, the Greek translation of the Hebrew Bible that became authoritative for Christianity; and the Samaritan Pentateuch, the text holy to the small offshoot of Judaism that still survives in two small communities in Israel and the West Bank. How did these differing versions arise?

The Samaritan Bible is limited to the Pentateuch, the Five Books of Moses. The most striking difference between the Samaritan Bible and the Jewish Bible is that the Samaritan Bible considers Mt. Gerizim, not Jerusalem, as God’s holy place on earth.

Samaritan origins can be traced to events following the conquest of the northern kingdom of Israel by Assyria in 722 B.C.E. Many of the inhabitants were exiled, and other conquered peoples were resettled in the lands of the northern kingdom, including Samaria. To the people of the ancient Near East, every land was thought to be protected by its local god, and the people who had been forcibly resettled in Samaria naturally added worship of the Jewish God to their religious practices. The southern kingdom of Judah, too, was to suffer dispersal, at the hands of the Babylonians in 587 B.C.E., and when those exiles returned, the people of Samaria asked to assist in rebuilding the Jerusalem Temple. But the leaders of the returning exiles, Ezra and Nehemiah, rebuffed them for having watered down their religious practices and for having intermarried with the neighboring, resettled peoples. That, at least, is the story as found in the Jewish Bible.

The Samaritans, not surprisingly, tell a different tale. They explain their name as deriving from the word shomerim (guardians) because they were the guardians of the true religion of Israel. According to their Chronicles, they are the descendants of Joseph’s sons, Ephraim and Manasseh, and have continuously inhabited their ancestral land. Though the Samaritans 027had offered to help their coreligionists who were returning from the Exile, they were rejected, mistreated and finally attacked by the Hasmonean king John Hyrcanus in 128 B.C.E. Their temple, located on Mt. Gerizim, rather than in Jerusalem, was destroyed.

Though the two versions outlined here assign the roles of hero and villain differently, both agree that by the second century B.C.E. the Samaritans had separated from normative—or, to use the more modern, scholarly term, common—Judaism.

The development of the Greek translation of the Hebrew Bible took a different path. It began in the wake of the Babylonian attack on Judah in the sixth century B.C.E., when some Jews fled to Egypt. Then, two and a half centuries later, Egypt, too, was conquered, by Alexander the Great. Alexander established cities organized on the Greek model in an attempt to unify his empire through a shared culture. The great metropolis of Alexandria attracted many Jews who adopted Greek as their language but who retained the religion of their forebears. By the third century B.C.E., their grasp of Hebrew was so 028tenuous that they needed a Greek translation of their sacred scriptures.

According to legend, in 270 B.C.E. Ptolemy II Philadelphus invited 72 scholars from Jerusalem to translate the Bible into Greek—hence the name Septuagint, from Interpretatio Septuaginta Seniorum (The Translation of the Seventy Elders).a When Christianity spread to the Hellenized world, the Septuagint became incorporated into Christian Bibles as the Old Testament.

One would expect that over many generations of copying, variations would creep into the three textual traditions. And that is what happened. The variations arose in several ways, including scribal errors, editing and polemical tampering.

One common error, called a homoeoteleuton, occurs when a scribe omits a phrase when his eye jumps from one word in the text he is copying to another appearance of the same word (or a similar one) a little farther in the text. That’s what seems to have happened in the Masoretic version of 1 Samuel 14:41: “Saul then said to the Lord, the God of Israel, ‘Show Thummim.’” Apparently the Masoretic scribe’s eye skipped from one occurrence of the word “Israel” to the next and he missed all the words in between, as shown by the fuller text preserved in the Septuagint: “Saul said to the Lord, the God of Israel, ‘Why have you not answered your servant today? Lord God of Israel, if this guilt lies in me or in my son Jonathan, let the lot be Urim; if it lies in your people Israel, let it be Thummim.’”

Some changes were made deliberately. Jewish tradition speaks of tikkun sopherim, scribal emendation, of disrespectful or misleading phrases. In 1 Kings 21:10, 13, for example, the euphemism “bless God” has replaced the unacceptable “curse God.”

Sometimes variations in the Septuagint indicate a misunderstanding of Hebrew poetic technique. The 029Masoretic version of Zechariah 9:9 reads “Rejoice greatly, daughter of Zion; shout, daughter of Jerusalem. Behold, your king is coming to you; he is just and triumphant, humble and riding on an ass, upon the foal of an ass.” In this passage, each key word is reinforced by a synonym or a parallel: rejoice//shout, Zion//Jerusalem, just and triumphant//humble and riding. But the translators of the Septuagint apparently missed the parallelism between ass//foal of an ass and instead pictured two animals—an ass and a foal. This misunderstanding becomes significant because the verse is used as a prooftext in Matthew 21:2–7, which describes Jesus’ entry into Jerusalem. Jesus sends two disciples to fetch an ass and a foal “to fulfill what was spoken by the prophet”; Matthew then quotes the passage in Zechariah and adds that the disciples did indeed bring Jesus an ass and a foal. The textual misunderstanding carried over into Christian art; some scenes of Jesus’ entry into Jerusalem show him straddling two animals!

Some variations in translations are really disagreements over how a verse should be punctuated. A good example is Isaiah 40:3. Most modern Bible scholars recognize that here, too, there is a parallelism at work: “A voice cries out, ‘In the wilderness prepare the way of the Lord, in the desert make straight a highway for our God.’” The Septuagint, however, reads, “A voice of one crying in the wilderness, ‘Prepare the way of the Lord.’” Is it a crying voice that is in the wilderness or a path? Matthew, Mark and Luke all quote this passage as the Septuagint has it; of course, for them John the Baptist was the voice crying in the wilderness and declaring the arrival of Jesus.

What do the Dead Sea Scrolls tell us about the three major textual traditions? In the majority of cases (about 60 percent of the biblical scroll manuscripts), the scrolls follow the Masoretic text. About 5 percent of the biblical scrolls follow the Septuagint version; another 5 percent match the Samaritan text; 20 percent belong to a tradition unique to the Dead Sea Scrolls; and 10 percent are “nonaligned.” The key point is that the readings in the scrolls show that many variations in the biblical text are of long standing, and are not simply errors in later transmission.

Just because a text is old, however, does not mean it is better. Ancient editors may have tried to correct difficult texts. Psalm 145 is an alphabetical acrostic: The first line begins with aleph, the first letter of the Hebrew alphabet, and so on through the alphabet—except that in the Masoretic text there is no line for nun(N). But the Septuagint versin does have a line beginning with nun-and a Dead Sea Scroll of the Psalms has the line as well. That would seem to clinch the case for the line’s originality. But scholars point out that the line uses one name for God-Elohim-while the rest of the psalm employs the personal name Yahweh. So the line may be a later addition after all, despite being found in both the Septuagint and the Dead Sea Scrolls.

The Dead Sea Scrolls have filled one large gap in the Bible. First Samuel 11:1 begins jarringly with the notice that “Nahash the Ammomite came and besieged Jabesh-gilead.” The announcement is abrupt—Nahash has not been previously mentioned, and we would expect him to be identified as Nahash, king of the 051Ammonites. Even worse, the text gives no reason for the attack. But a Dead Sea Scroll text of Samuel contains two preceding sentences, which contain the expected “Nahash, king of the Ammonites” and a description of how seven thousand of his enemies had found refuge in Jabesh-gilead, making his attack understandable. Most Bible scholars accept these verses as authentic. The New Revised Standard Version includes them in its text of 1 Samuel, and other translations cite them in a note.

The Dead Sea Scroll version of 1 Samuel contains many other readings that have been adopted by modern translations. By one count, the New Revised Standard Version of 1 Samuel incorporates 110 alternatives to the Masoretic text; the New English Bible uses 160; and the New American Bible, 230.

The evidence from the Dead Sea Scrolls must be used carefully, however. Large portions of Samuel, Isaiah and Jeremiah are represented in the scrolls, but other biblical books appear only in small fragments. They may not be biblical texts at all, but rather paraphrases from commentaries or prayers.

Even large chunks of text present problems. The Psalms Scroll contains a selection of psalms, mostly from the last third of the Psalter. James A. Sanders, who edited the Psalms Scroll for publication, maintains that differences in content and order between the Psalms Scroll and the traditional text prove that alternative psalters existed as late as the first century C.E. But other scholars counter that the differences prove that the Psalms Scroll was a prayer book, not a biblical text.

The Dead Sea Scrolls have already made their mark on modern Bible translations. Even when they do not settle textual questions once and for all, the scrolls prove that the Septuagint and the Samaritan Bible have ancient pedigrees and may preserve accurate readings. Bible translators now have an important new body of evidence to help them decide how best to settle problems in the text—evidence not available to earlier generations of scholars. William Foxwell Albright’s exclamation when the scrolls were discovered—he called the Isaiah Scroll “the greatest manuscript discovery of modern times!”—has been proved true many times over.1

Ancient versions of the Bible are far from error-free. Happily, a better understanding of the Dead Sea Scrolls and of how manuscripts evolved has helped resolve some of the vexing textual problems.

You have already read your free article for this month. Please join the BAS Library or become an All Access member of BAS to gain full access to this article and so much more.

Already a library member? Log in here.

Institution user? Log in with your IP address or Username

Footnotes

See Leonard J. Greenspoon, “Mission to Alexandria: Truth and Legend About the Creation of the Septuagint, the First Bible Translation,” BR 05:04.

Endnotes

This article was adapted from Harvey Minkoff, Mysteries of the Dead Sea Scrolls (Owing Mills, MD: Ottenheimer Publishers, 1998). It draws on information from the following sources: Edward M. Cook, Solving the Mysteries of the Dead Sea Scrolls (Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, 1994), appendix; Moshe Greenberg, “The Stabilization of the Text of the Hebrew Bible, Reviewed in the Light of the Biblical Materials from the Judean Desert” and “The Use of the Ancient Versions for Interpreting the Hebrew Text,” in Studies in the Bible and Jewish Thought (Philadelphia: Jewish Publication Society, 1995); Minkoff, ed., Approaches to the Bible, 2 vols. (Washington, DC: Biblical Archaeology Society, 1994–1995), vol. 1, parts 1–2; James A. Sanders, “Understanding the Development of the Biblical Text,” in Hershel Shanks, ed., The Dead Sea Scrolls After Forty Years (Washington, DC: Biblical Archaeology Society, 1991); Harold Scanlin, The Dead Sea Scrolls and Modern Translations of the Old Testament (Wheaton, IL: Tyndale House, 1993); Lawrence H. Schiffman, Reclaiming the Scrolls (Philadelphia: Jewish Publication Society, 1994), chap. 10; Adam S. van der Woude, “Tracing the Evolution of the Hebrew Bible,” BR 11:01; James C. VanderKam, The Dead Sea Scrolls Today (Grand Rapids,MI: Edermans, 1994) chap 5.