Southwest Missouri State University professor Charles Hedrick opens the discussion by setting the stage for us, as we asked him to do, without revealing his own belief in the authenticity of Secret Mark.

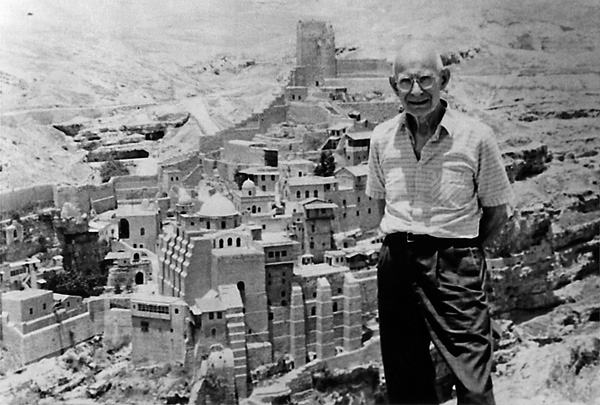

In 1958 Morton Smith, a 43-year-old Columbia University history professor, spent the summer looking for ancient manuscripts and handwritten entries in old printed books at monasteries in Turkey, Greece and the Holy Land. One of his destinations was the storied Greek Orthodox monastery of Mar Saba in the Judean wilderness, roughly a dozen miles southeast of Jerusalem.

Smith was no stranger to the place. Seventeen years earlier he had spent two months of seclusion there, fully participating in its meditative way of life. Day began in the isolated Byzantine structure with morning worship from midnight until 6:00 a.m., only to be resumed again in the afternoon from 1:30 to 3:00. Around 5:00 p.m. the monks observed evening prayers and then slept till midnight. “Between the services was silence—the silence of the desert, no voices, no sounds of animals, not even wind in the trees,” as Smith described it.1 It was a life of worship, meditation and spiritual reflection.

After his first trip to Mar Saba in 1941, Morton Smith was ordained an Episcopal deacon (in 1944). Although not officially, in effect he later left the clergy, however, to pursue the scholarly life. He once quipped to the eminent Yale scholar E.R. Goodenough that “he was passing out cigars because he was no longer a Father.”2 He remained a lifelong bachelor.

On his second visit to the monastery (in 1958), Smith excused himself from the daily liturgy in order to give complete focus to his manuscript search. He later published a catalogue of the manuscripts he discovered at Mar Saba.3

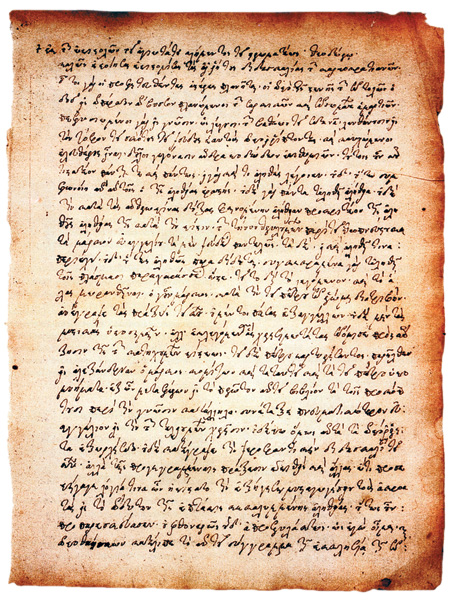

Each morning he would climb the stairs to the cluttered tower library together with a monk assigned to sit with him while he worked. There he found manuscripts and nearly 500 books scattered hither and yon and jammed into the bookcase. Each day he was permitted to take a few books to his monk’s cell for study. One of the books he examined was written in Latin and Greek, lacking a cover and a title page. It later turned out to be a 1646 edition of the letters of Ignatius of Antioch edited by Isaac Voss.4 The final pages of the printed book had originally been blank, but now they contained a handwritten Greek manuscript of the 18th century (judging by the handwriting), which purported to be a copy of a letter by the second-century church leader Clement of Alexandria.

The Clement letter is addressed to one Theodore, otherwise unknown. Theodore apparently had asked Clement questions about a Secret Gospel of Mark, and Clement answers by quoting two excerpts from the Secret Gospel.

Smith photographed the letter and at the end of the summer returned to his teaching duties at Columbia. He spent the next 15 years studying the handwritten manuscript, conferring with colleagues and preparing it for publication. In 1973 Smith simultaneously published two books on the Clement letter: one a scholarly book titled Clement of Alexandria and a Secret Gospel of Mark and the other a popular book titled The Secret Gospel: The Discovery and Interpretation of The Secret Gospel According to Mark. Both books exploded like bombshells on the reading public, but in the academic guild it was a “nuclear event.”5

Clement’s letter to Theodore appears to be something of a diatribe against the Carpocratians, a Gnostic-Christian group whose members (Clement says in the letter) “wander … into a boundless abyss of the carnal and bodily sins” and embrace “blasphemous and carnal doctrine” (Smith’s translation). Clement elsewhere accuses them of engaging in orgies: They “overturn the lamps and so remove the light that would uncover the shame of their dissolute ‘righteousness’ and unite with whom they will” (Stromata III.2). Another second-century writer, Irenaeus, accused them of “practicing magic arts and incantations, love potions and love feasts” and of living dissolute lives (Against Heresies I.25.3). The Carpocratians further claimed, according to Irenaeus, that one must experience “everything ungodly and impious” in order to free one’s soul from the world (Against Heresies I.25.4). In his letter, Clement commends Theodore for “silencing the unspeakable teachings of the Carpocratians,” and then proceeds to his own denunciations of them.

More particularly, Clement quotes from a Secret Gospel of Mark. According to Clement, Mark had written his original gospel in Rome containing material appropriate for beginners in faith. This version did not even “hint” at the “secret” (or “mystic”) things. When Mark came to Alexandria, however, he added to his original gospel other material suitable for those aspiring to reach a higher level of knowledge in the faith. This version Clement described as “a more spiritual gospel,” which was intended for use by those “being perfected” in the faith.

According to the Clement letter, Carpocrates, for whom the Carpocratian sect was named, secured a copy of “the Secret Gospel” by duping a certain presbyter of the church in Alexandria, where Mark had left the Secret Gospel when he died. Carpocrates then “doctored” Mark’s Secret Gospel by adding material to it—in effect mixing “holy words with utterly shameless lies.” Thus, although there was a certain amount of truth in what the Carpocratians said about the Secret Gospel of Mark, nevertheless in the form used by the Carpocratians, it was, according to Clement, false and misleading.

Theodore had apparently asked Clement certain specific questions, which are not reiterated by Clement. Clement refutes the false statements of the Carpocratians simply by quoting two excerpts from the “undoctored” version of Secret Mark, one long and the other but a single sentence.

The first quotation from Secret Mark describes the resuscitation of a young man who had died. The youth’s sister pleads for help from Jesus, and both go to a garden tomb from which a great cry is heard. Jesus rolls away the stone from the door of the tomb, enters and resuscitates the youth. The youth “looking upon [Jesus], loved him.” They go to the youth’s house, “for he was rich.” Jesus remains there for six days, and then advises the young man what he must do. The unnamed youth then comes to Jesus in the evening “wearing a linen cloth over his naked body. And he remained with him that night, for Jesus taught him the mystery of the kingdom of God.”

Clement implies that the Carpocratian version of the Secret Gospel contained an offensive statement not found in Mark’s longer gospel, and refutes it; “Naked man with [or on] naked man” is not found in Secret Mark, Clement insists. Clement counsels Theodore to deny under oath that the Carpocratian version of Secret Mark was written by Mark. And even if the Carpocratians were to say something true, Theodore should not agree with them.

Smith briefly describes his own feelings at his startling discovery. He felt as if he were “walking on air.”6 He photographed the letter of Clement three times and continued on with his search for other manuscripts.

When Smith published the results of his study of the Clement letter 15 years after its discovery, scholarly responses were harshly negative, even caustic. Many of the published reactions were inflammatory personal assaults on Smith himself,7 and in particular at his interpretation of the text, rather than concerned with the question of whether or not the letter was forged. (The forgery issue was first raised by Quentin Quesnell in 1975.8) Smith’s conclusion was that Clement’s letter was a genuine second-century text and that Secret Mark was also genuine—from the late first century. The Secret Gospel of Mark demonstrated that the Jesus movement had begun with a mystery-religion baptismal initiation: Jesus baptized each of his closest disciples into the mystery of the kingdom of God, “singly and at night.” In his larger study Smith wrote: “In this baptism the disciple was united with Jesus. The union may have been physical … (there is no telling how far symbolism went in Jesus’ rite), but the essential thing was that the disciple was possessed by Jesus’ spirit.”9 This is how Smith put it in his more popular book: The disciple ecstatically “entered the kingdom of God, and was thereby set free from the laws ordained for and in the lower world. Freedom from the law may have resulted in completion of the spiritual union by physical union.”10

Moreover, according to Smith, the account in Secret Mark had traits relating it to the incident in Mark 14:51–52 in which a young man followed Jesus in the evening “wearing nothing but a linen cloth” over his naked body.11 Smith argues further that the church in the second and third centuries covered up the historical datum that Jesus began his movement with a “baptism into the mystery of the kingdom of God,” as reflected in Secret Mark.12

It is not difficult to imagine how Smith’s interpretation of Secret Mark antagonized scholars having close personal religious ties to a community of faith. Although Smith never really developed his suggestion that the uniting of the disciple with Jesus may have been physical, this was the one line in the book that most stirred the ire of the academic guild. Further, it is the one line that raises the issue of homosexuality, which some think is actually affirmatively stated in the first excerpt of Secret Mark only by how they interpret it.

Smith had the reputation of being a difficult man—austere, intense, even haughty, a man who did not suffer fools gladly. These personal reactions to Smith no doubt added to the hostility against him.

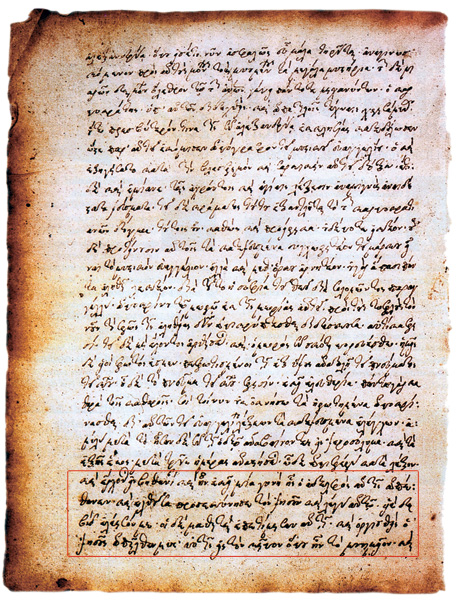

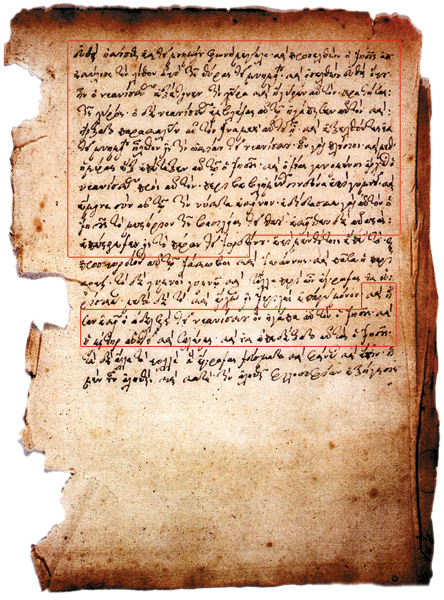

In light of the issues raised by Smith’s two books, efforts were made to see and examine the Voss book containing the letter of Clement, which Smith claimed to have found in the Mar Saba library. In 1976, three years after the publication of Smith’s books on Secret Mark, three Hebrew University scholars (David Flusser, Shlomo Pines and Guy G. Stroumsa, then a graduate student at the Hebrew University), in the company of an official of the Greek Orthodox Church (Archimandrite Meliton), went to Mar Saba and managed to “relocate” the book, after some searching around in the tower library where Smith left it. Because of its significance, all concurred that it should be taken to Jerusalem and secured in the Patriarchate library. They hoped that a scientific test of the ink would demonstrate the date of the inscription of Clement’s letter, but such a test was not permitted. Subsequent scholars who visited the library later were not permitted to see the book.

In 1980 Thomas Talley, a professor at General Theological Seminary in New York, reported in an article that he was not allowed to see the letter because it had been removed from the book and was being “repaired.”13 Shortly after the book was deposited in the Patriarchate library in Jerusalem, the librarian (Kallistos Dourvas) removed the two folios containing the Clement letter in order to photograph it. He then replaced the two loose folios at the back of the book.14 And then the Voss book itself was “misplaced” in the library and could not be located. In June 2000, however, the Voss volume was relocated in the Patriarchate library, but the two folios containing the letter of Clement were missing. They are still missing.

Morton Smith continued to publish on the Clement letter until his death in 1991.

In 2005 Scott Brown published his revised doctoral dissertation (Mark’s Other Gospel: Rethinking Morton Smith’s Controversial Discovery). It was the first thorough review of Smith’s publications. Brown disagreed with Smith’s interpretation and argued that the excerpts from Secret Mark should be read in the context of the canonical Gospel of Mark with reference to the distinctly Marcan literary techniques they employ. This interpretation had the effect of neutralizing Smith’s theory that the longer excerpt of Secret Mark reflected a mystery-religion’s baptismal initiation. More importantly, Brown concluded that the Clement letter was a genuine second–third-century text, and that Secret Mark was a longer gospel likely written by the very same author who had written the original Gospel of Mark.

Brown’s volume was immediately followed by Stephen Carlson’s The Gospel Hoax: Morton Smith’s Invention of Secret Mark.15 The title says it all. Smith perpetrated the forgery to get back at his colleagues for not recognizing his genius.16 Carlson, a lawyer and currently a Ph.D. student in the Graduate Program in Religion (New Testament) at Duke University, claims to have found clues “in places scholars do not normally look.” Carlson relies on anomalies in the text that in his view confirm the forgery. For example, the handwriting reflects a forger’s tremor, and certain letterforms closely resemble the forms of these same letters found in marginal notations written by Smith.

In 2007 a monograph by Peter Jeffery, professor of music history at Princeton, also charged that the Clement letter was a forgery.17 Smith’s interpretation, Jeffery argues, reflects a “tale of ‘sexual preference’ that could only have been told by a 20th-century Western author.”18 Jeffery bases his conclusions on an analysis of Morton Smith’s character, largely based on Smith’s reading of Secret Mark as homoerotic and on what he claims are modern homosexual anachronisms in the text. He also relies on alleged anachronisms regarding the development of Christian liturgy.

The stalemate with regard to Secret Mark continues. Although some scholars have made use of the text in their analysis of Christian origins, the focus of the discussion has remained on the man who discovered—or forged—the text.

MLA Citation

Endnotes

1.

Morton Smith, The Secret Gospel: The Discovery and Interpretation of The Secret Gospel According to Mark (New York: Harper and Row, 1973), p. 4.

2.

Allan J. Pantuck, “Can Morton Smith’s Archival Writings and Correspondence Shine Any Light on the Authenticity of Secret Mark?” Paper presented at the Society of Biblical Literature Meeting, Boston 2008: Synoptic Gospels Section (24–97). He was referring to his activity as an “Anglican Father”; Smith never married (Pantuck, e-mail to Hedrick, dated December 28, 2008).

3.

In the periodical of the Patriarchate Nea Sion: “Hellenika Cheirographa en tei Monei tou Hagiou Sabba,” 52 (1960), pp. 110–125, 245–256.

4.

For photographs see Charles W. Hedrick and Nikolaus Olympiou, “Secret Mark: New Photographs, New Witnesses,” The Fourth R 13, vol. 5 (2000), pp. 3–11, 14–16.

5.

Morton Smith, Clement of Alexandria and a Secret Gospel of Mark (Cambridge: Harvard Univ. Press, 1973); Smith, The Secret Gospel.

6.

Smith, The Secret Gospel, p. 13.

7.

See in particular Shawn Eyer, “The Strange Case of the Secret Gospel According to Mark: How Morton Smith’s Discovery of a Lost Letter by Clement of Alexandria Scandalized Biblical Scholarship,” Alexandria: The Journal for the Western Cosmological Traditions 3 (1995), pp. 103–129. See the surveys of the reactions in Scott G. Brown, Mark’s Other Gospel: Rethinking Morton Smith’s Controversial Discovery (Studies in Christianity and Judaism 15; Waterloo, Ontario: Wilfred Laurier Univ. Press, 2005), pp. 6–19; Charles W. Hedrick, “The Secret Gospel of Mark. Stalemate in the Academy,” Journal of Early Christian Studies 11 (2003), pp. 135–138.

8.

Quentin Quesnell, “The Mar Saba Clementine: A Question of Evidence,” The Catholic Biblical Quarterly 37 (1975), pp. 48–67.

9.

Smith, Clement of Alexandria, p. 251.

10.

Smith, The Secret Gospel, p. 114.

11.

Smith, Clement of Alexandria, p. 109.

12.

Smith, Clement of Alexandria, p. 252.

13.

Thomas Talley, “Le temps liturgique dans l’Église ancienne. État de la recherché,” La Maison-Dieu 147 (1981), p. 52.

14.

For photographs by Dourvas, see Hedrick and Olympiou, “Secret Mark,” pp. 3–11, 14–16.

15.

Stephen Carlson, The Gospel Hoax (Waco, TX: Baylor Univ. Press, 2005).

16.

Carlson, The Gospel Hoax, pp. 73–80.

17.

Peter Jeffery, The Secret Gospel of Mark Unveiled: Imagined Rituals of Sex, Death, and Madness in a Biblical Forgery (New Haven: Yale Univ. Press, 2007).

18.

Jeffery, The Secret Gospel of Mark Unveiled, p. 50.