Southern Arabia is 1,200 miles south of Israel. Naturally, skepticism about the reality of trade between South Arabia and Israel in ancient times seems justified.

Yet the Bible documents this trade quite extensively—most famously in the supposed affair between King Solomon and the Queen of Sheba. And the land of Sheba is referred to two dozen times in the Hebrew Bible.

Without addressing the historicity of the personal relations between Solomon and the queen of this South Arabian kingdom (or queendom?), I think it can be shown that the international trade between Judah and southern Arabia very probably existed as early as the latter half of the tenth century B.C.E.—the time of King Solomon.

Well-known neo-Assyrian texts document South Arabian trade with the Middle Euphrates region as early as the beginning of the ninth century B.C.E,1 and archaeologists have persuasively argued that international trade between the southern Levant and South Arabia began at the end of the second millennium B.C.E.2

Moreover, a critical study of 1 Kings 10:1–10, 13, the story of the Queen of Sheba’s visit to King Solomon, reveals that once the few later redactions (edits) of the text are peeled away, the core text was probably written toward the end of the tenth century B.C.E.3 This core text—the earliest redaction—was probably taken from (or written by the author of) the now lost “Acts of Solomon,” a text referred to in 1 Kings 11:41.4

Now, in a startling bronze inscription that has surfaced on the antiquities market,5 South Arabian trade with “the towns of Judah” has been documented at about the end of the seventh century B.C.E.6

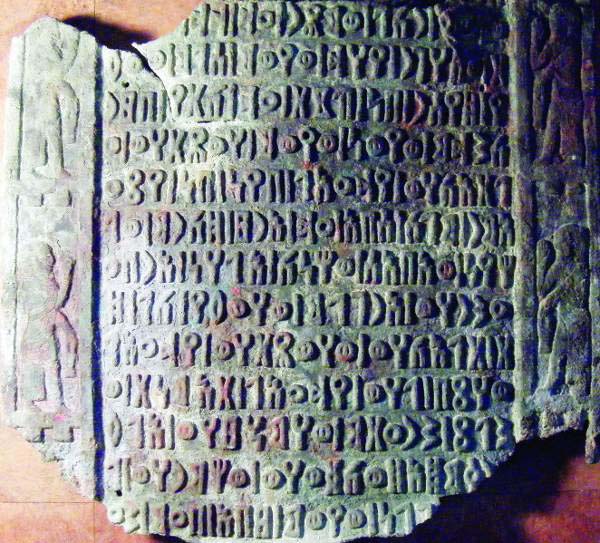

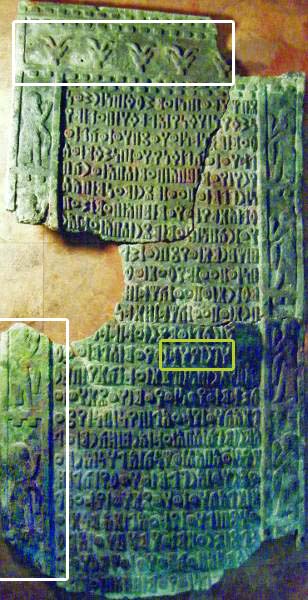

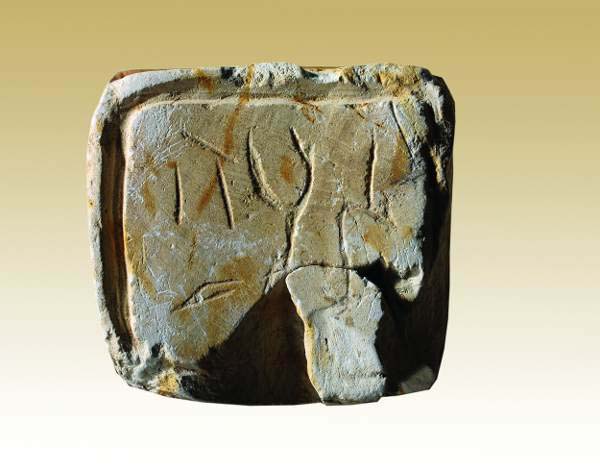

The newly discovered inscription is apparently a memorial inscription that was displayed on the wall of a temple. It is broken, and only three large pieces from the top of the inscription have been preserved. Although the lower part is missing, parts of at least 25 lines of the inscription are extant.

The inscription is written in Sabaean, the language of the South Arabian kingdom of Sabaea (Sheba) and adjacent areas. It is written in the South Arabian alphabet.

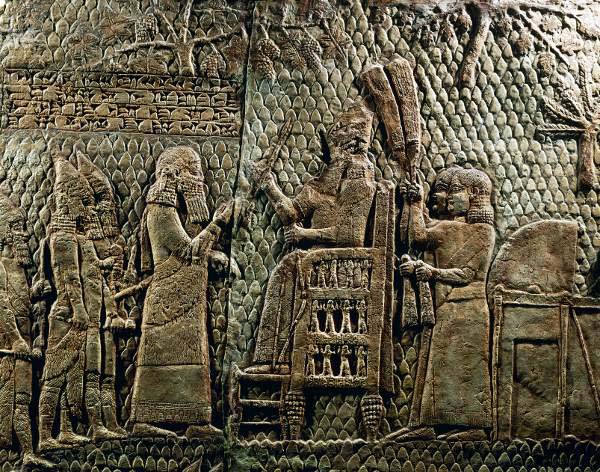

The inscription is surrounded by a typical South Arabian frieze: The top part originally contained six ibex heads, five of which have fully or partially survived (for more about the ibex in South Arabian art, see Worldwide). The two lateral friezes each depict several men in Assyrian dress.

The author of the text is a man named Sabahhumu from the South Arabian city of Nashq, an ancient and long-known site now called Al-Bayda. Sabahhumu is a messenger of the king of Sheba, “Yada’il Bayin, son of Yitha’amar.” Sabahhumu thanks the main Sabaean god Almaqah for having saved him from many dangers, especially in wars, and he dedicates all his family and properties to the god.

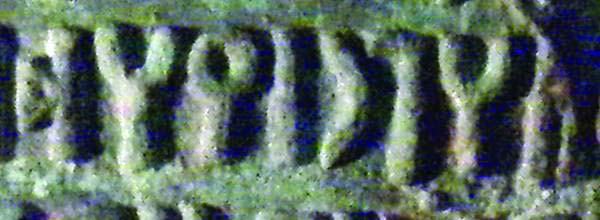

The text also describes an important trade expedition to “Dedan, [Gaz]a7 and the towns of Judah” (’HGR YHD).

This is the first time “the towns of Judah” are mentioned in a South Arabian inscription. Indeed, it is the first mention of Judah in a South Arabian inscription from the first millennium B.C.E.

The phrase “towns of Judah” is used frequently in the Bible. For example, at the end of the eighth century B.C.E., Sennacherib, ruler of Assyria, sent his troops against the fortified “towns of Judah” (2 Kings 18:13; Isaiah 36:1). Three centuries later, Nehemiah (11:3) refers to the “towns of Judah” that seem then to constitute a Persian province. The same can be seen in the numerous references to the “towns of Judah” in the book of the prophet Jeremiah (Jeremiah 1:15, 4:16, etc.) from the end of the First Temple period.

Dating the new inscription is difficult and complicated, but I have argued in a scientific paper, based on the text’s mention of a contemporary “war of Chaldea and Iawan,” that it should be dated to about 600 B.C.E.8 Both inscriptions and archaeological finds document the prosperity of “the towns of Judah” at the end of the seventh century B.C.E., shortly before the Babylonian destruction of Jerusalem and Solomon’s Temple in 587/6 B.C.E.

Lily Singer-Avitz has already argued that the archaeological excavations at Beersheba reveal traces of the South Arabian trade from at least as early as the eighth century B.C.E.,9 especially as evidenced by a probable South Arabian graffito.10 And a chiseled Sabaean letter has also been discovered in Aroer, a site located at a major crossroads in the Negev.11 In addition, excavations in Jerusalem uncovered at least one clear fragmentary South Arabian inscription and two probable ones dating to the city’s 587/6 B.C.E. destruction.a12

Ezekiel describes this international trade at some length (Ezekiel 27). In a prophecy against the Phoenician city of Tyre, he refers to merchants of “Judah and the land of Israel” (Ezekiel 27:17). The prophet then mentions Dedan, a city in northern Arabia that was known as a source of coarse woolens for saddlecloths (Ezekiel 27:20). In the new bronze inscription, “Dedan” is again identified as a destination in this international trade. This oasis was on the caravan route from South Arabia to Gaza and Judah, as explicitly mentioned in the new inscription. And Ezekiel also mentions merchants of Sheba (Ezekiel 27:22).

If the past is any guide, we can expect more inscriptions documenting trade between South Arabia and Judah. Perhaps this new inscription is only the beginning. But even at this point, it seems clear that the Bible’s reference to trade between southern Arabia, the kingdom of Judah and the southern Levant is no myth.

MLA Citation

Footnotes

1.

See “

Endnotes

1.

Mario Liverani, “Early Caravan Trade between South Arabia and Mesopotamia,” Yemen 1 (1992), pp. 111–115.

2.

Israel Finkelstein, “Arabian Trade and Socio-Political Conditions in the Negev in the Twelfth-Eleventh Centuries B.C.E.,” Journal of Near Eastern Studies 47 (1988), pp. 241–252; I. Finkelstein, Living on the Fringe: The Archaeology and History of the Negev, Sinai and Neighbouring Regions in the Bronze and Iron Age, Monographs in Mediterranean Archaeology 6 (Sheffield, England: Sheffield Academic Press, 1995), pp. 120–126; Michael Jasmin, “Les Conditions d’émergence de la Route de l’encens à la Fin du IIe Millénaire avant notre Ère,” Syria 82 (2005), pp. 49–62.

3.

See André Lemaire, “La Reine de Saba à Jérusalem: la Tradition Ancienne Reconsidérée,” in Ulrich Hübner and Ernst Axel Knauf, eds., Kein Land für sich allein: Studien zum Kulturkontakt in Kanaan, Israel/Palästina und Ebirnâri für Manfred Weippert, Orbis Biblicus et Orientalis 186 (Freiburg/Göttingen: Universitätsverlag/Vandenhoeck und Ruprecht, 2002), pp. 43–55.

4.

André Lemaire, “Wisdom in Solomonic Historiography,” in John Day, Robert Gordon, H.G.M. Williamson, eds., Wisdom in Ancient Israel: Essays in Honour of J.A. Emerton (Cambridge: Cambridge Univ. Press, 1995), pp. 106–118.

5.

See François Bron and André Lemaire, “Nouvelle inscription Sabéenne et le Commerce en Transeuphratène,” Transeuphratène 38 (2009).

6.

In my view, there is no question that the inscription is authentic. This view is shared by two South Arabian epigraphers who have been working in the field for more than 40 years each: François Bron, who has published the inscription with me, and Christian Robin, who recently cited the inscription in a communication to the Académie des Inscriptions et Belles-Lettres (Paris).

7.

Gaza is also mentioned later in Minaean inscriptions, in similar contexts, thereby making the reconstruction here quite certain.

8.

“New Perspectives on the Trade between Judah and South Arabia,” in Meir Lubetski, ed., New Inscriptions and Seals Relating to the Biblical World (forthcoming).

9.

“A Gateway Community in Southern Arabian Long-Distance Trade in the Eighth Century B.C.E.,” Tel Aviv 26 (1999), pp. 3–74, esp. 40–61.

10.

Bron and Lemaire, “Nouvelle inscription Sabéenne et le Commerce en Transeuphratène,” Transeuphratène 38 (2009), p. 51.

11.

Yifat Thareani-Sussely, “Desert Outsiders: Extramural Neighbourhoods in the Iron Age Negev,” in Alexander Fantalkin and Assaf Yasur-Landau, eds., Bene Israel: Studies in the Archaeology of Israel and the Levant During the Bronze and Iron Ages in Honour of Israel Finkelstein (Leiden/Boston: Brill, 2008), pp. 198–212 and 288–303, esp. 208 and 302.

12.

Maria Höfner, “Remarks on Potsherds with Incised South Arabian Letters,” in Donald T. Ariel, ed., Excavations at the City of David 1978–1985 Directed by Yigal Shiloh. Vol. 6, Qedem 41 (Jerusalem: Institute of Archaeology, The Hebrew Univ., 2000), pp. 26–28.