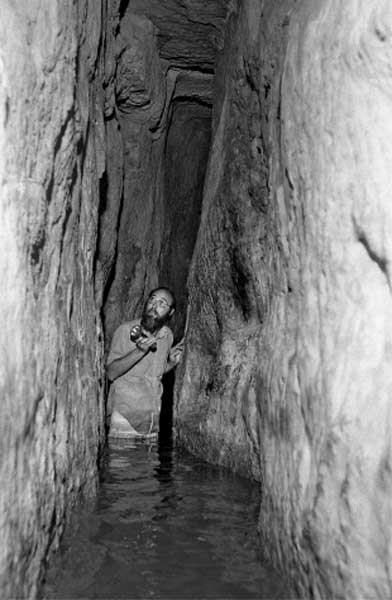

I’ve been writing about Hezekiah’s Tunnel for 35 years. (I can be seen with a long beard standing in my undershorts up to my hips in water in the picture of Hezekiah’s Tunnel in the standard archaeological encyclopedia of the Holy Land;1 the photo was taken in 1972.) A trip through the tunnel—from the first foot into the water, bending down to navigate a less-than-5-foot ceiling, finding the place where the two crews of tunnelers met, exploring the “false” tunnels, examining the place where the famous Siloam Inscription was carved, looking up at the ceiling nearly 17 feet above the floor, to coming out into the old Siloam Pool—can be one of most exciting adventures on a trip to Jerusalem. And with every scientific effort to understand this extraordinary tunnel, it becomes a more remarkable achievement.

At more than 1,700 feet (533 meters), it was the longest tunnel ever built up to that time without intermediate man-made shafts. Say what you want about the supposedly rinky-dink kingdom of Judah in the eighth century B.C.E., but King Hezekiah had pretty brainy construction engineers who knew and employed some remarkable techniques to create a tunnel going from one side of Jerusalem to the other. It starts at the Gihon Spring, Jerusalem’s only natural source of water, and curves around to the Siloam Pool on the other side of the City of David.

Hezekiah built the tunnel in anticipation of a threatened siege of the city by the Assyrian monarch Sennacherib. The Gihon Spring lay near the floor of the Kidron Valley, outside the eastern city wall. In peacetime Jerusalemites would walk a few feet outside the city to get their water, something they could not do if the city were under siege. The tunnel would make water available inside the city.

The Bible describes Sennacherib’s tactics quite dramatically. His messengers, sent to threaten Hezekiah, spoke from the walls of Jerusalem within the hearing of the people. Hezekiah’s representatives asked Sennacherib’s men to speak in Aramaic (the diplomatic language of the day) instead of Hebrew so the people would not understand: “Please, speak to your servants in Aramaic, for we understand it; do not speak to us in Judean in the hearing of the people on the wall” (2 Kings 18:26). Sennacherib’s envoys replied that it was precisely to the people on the wall that they wanted to speak. “[The people on the wall] will have to eat their dung and drink their urine” (2 Kings 18:27).

So, among other preparations, Hezekiah built a tunnel to bring water into the soon-to-be-besieged city: “When Hezekiah saw that Sennacherib had come, intent on making war against Jerusalem, he consulted with his officers and warriors about stopping the flow of the springs outside the city … [Hezekiah] stopped up the spring of water of Upper Gihon, leading it downward west of the City of David (2 Chronicles 32:2–3, 30). In summarizing the good deeds of Hezekiah, the account in Kings records “how he made the pool and the conduit and brought the water into the city” (2 Kings 20:20).

Whether because of the tunnel or a miracle (see 2 Kings 19:35), Sennacherib’s siege was unsuccessful. Even he admitted this: In a famous cuneiform inscription, the Assyrian monarch brags that he had Hezekiah cornered in Jerusalem “like a bird in a cage,” but Sennacherib makes no claim to capturing the bird or conquering the city.2

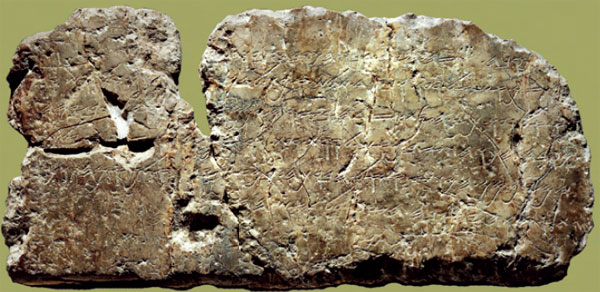

The course of the tunnel, however, has always been a mystery. We know that it was dug by two teams digging from opposite ends. We know this, first of all, from the famous Siloam Inscription found in 1880 carved in the tunnel wall, describing how the two teams of tunnelers met:

…This is the account of the breakthrough. While the laborers were still working with their picks, each toward the other, and while there were still three cubits to be broken through, the voice of each was heard [through the rock] calling to the other, because there was a zdh [split? crack? overlap? resonance?3] in the rock to the south and to the north. And at the moment of the breakthrough, the laborers struck each toward the other, pick against pick. Then the water flowed from the spring to the pool for 1,200 cubits. And the height of the rock above the heads of the laborers was 100 cubits.

Ever since Hezekiah’s Tunnel was discovered in the mid-19th century by the American explorer and Orientalist Edward Robinson, scholars have puzzled over how the two teams of tunnelers, digging from opposite ends of the city, managed to meet in the middle, especially considering the winding route the tunnel took.

And if they were so smart, why didn’t they take a more direct route? A straight line would have produced a tunnel of about 1,050 feet. The circuitous route they took was 1,748 feet, about 700 extra feet or two-thirds again as much as the tunnel would have been if they had dug in a straight line.

Between 1978 and 1982, Yigal Shiloh directed a major excavation of the City of David and its water systems. His staff included a geologist, Dan Gill, from the Geological Survey of Israel, who studied Hezekiah’s Tunnel to answer these and other questions. In the end, Gill adopted and expanded an explanation put forward as early as 1929 by an English architect named Henry Sulley,4 namely that a small natural tunnel or stream preceded and guided the tunnelers who dug Hezekiah’s Tunnel. They simply enlarged what had been there before. A prominent Israeli archaeologist named Ruth Amiran adopted the suggestion in the 1960s not long before Shiloh began his excavation.5

Gill expanded this explanation with a thorough study of the geology of the site.6 Hezekiah’s Tunnel, said Gill in a path-breaking article in BAR,a was “fashioned essentially by skillful human enlargement of natural (karstic) dissolution channels.” The natural channel was created by water in effect gouging out the porous, permeable limestone as it flowed out of the Gihon Spring.

A new study by Aryeh Shimron and Amos Frumkin, however, now proves this theory wrong and goes on to explain how the two teams of tunnelers really found each other.7

Some of the reasons they give for rejecting the karstic-dissolution-channel theory may now seem obvious:

Look at the plan of Hezekiah’s Tunnel in the area where the tunnelers met. The meeting point of the two teams of tunnelers is clear: It is at a point where the pickax marks on the tunnel wall change directions. On either side of this point are short twists and turns in direction. These twists and turns start about a hundred feet from where the two teams met. They seem to reflect the efforts of each team to find the other, just as described in the Siloam Inscription, referred to above. If the tunnelers could follow a karstic dissolution channel created by water, why did they have so much trouble finding each other when they were only a hundred feet apart?

When Gill submitted his article to BAR, I raised this question. He agreed to discuss it in a footnote: The meandering near the meeting point “may simply be the course of the original karst conduit. That is the best answer I can think of,” he wrote. As I commented in a later publication, “It’s not a very satisfying answer.”8

There’s another problem with the karst theory: There are three “false” tunnels in Hezekiah’s Tunnel that lead off in another direction, but stop very quickly. Two of these false tunnels are beautifully finished and extend only for a few feet. The third is rudimentary. All three, however, are near the meeting point. It looks like these false tunnels were simply mistakes where the tunnelers went off in the wrong direction, perhaps misled by echoes as they attempted to reach the team on the other side. These false tunnels also seemed to me to be a problem with Gill’s hypothesis. This, too, he answered in a footnote, suggesting that the karstic tunnel may have forked at these points and the tunnelers took the wrong fork, only to quickly discover their mistake. Alternatively, Gill suggested the false tunnels may have been intentionally created to allow two-way traffic for maintenance personnel who would periodically clean the channel of debris. As I later wrote: “Both explanations seem to me forced.”

Now Shimron and Frumkin add to these considerations some formidable scientific arguments. Shimron mapped in detail the direction of hundreds of geological joints and fractures that cut the ceiling and walls of the tunnel. Karstic dissolution tunnels form by acidic waters percolating through the rock, which occurs where the water has easy access through the rock—that is, along fractures and joints. This widens the cracks, forming subterranean tunnels, chimneys and caves. What is important is that these voids form parallel along a single or group of such openings. Shimron’s structural mapping of Hezekiah’s tunnel shows that almost all the fractures and joints cut across the tunnel ceiling and walls. Therefore, the tunnel cannot originally have been a natural karstic-formed geological feature.

Shimron also studied the plasters and natural sedimentary deposits in the tunnel. There were four different kinds of plaster in the tunnel. The oldest plaster was succeeded by Byzantine plaster, next by a Mameluke-period plaster, and finally by a plaster applied in the early 20th century by the infamous Parker Mission.b Natural sedimentary deposits laid down from running water (tufa) and water seeping through tunnel walls (flowstone, a kind of stalactite attached to tunnel walls) also occur along various segments of the tunnel. Patches of the oldest plaster were preserved beneath flowstone, a critical finding, as we shall see.

Numerous drill cores that were collected from along the tunnel floor revealed that tufa and siltstone covered all the plaster layers but were never found beneath the oldest plaster. This demonstrated that there was no percolating water and thus no incipient channel here that was later widened by Hezekiah’s tunnelers. Had there been a karstic channel to guide the tunnelers, sediments deposited from the running water (such as covered the plaster) would have been found beneath the oldest plaster. The absence of these sedimentary deposits also shows that the ancient plaster was applied soon after the tunnel was dug, before the natural sedimentation process could begin.

What if the stream along the karstic tunnel was only a trickle? you may ask. What if the drill cores missed this narrow stream? The new study has an answer: Frumkin examined more than a thousand karstic cave passages in and around Jerusalem. He found that the cross-section of these passages is, on average, larger than the width of Hezekiah’s Tunnel. Based on these studies, Shimron and Frumkin conclude that “total obliteration of a karst conduit by the narrow Siloam [Hezekiah’s] Tunnel is virtually impossible.”

The researchers were also able to confirm the date of the tunnel’s construction. Perfectly preserved twigs were recovered in the oldest plaster and were subjected to carbon-14 examination. The results were well within Iron Age II, the period of Hezekiah. As the authors state, this age is also “sustained by the paleography and philology of the Siloam Inscription.”c Thus, their work confirmed the correlation between the archaeology and the Biblical account.

But we are still left with the question: How in the world did the two teams of tunnelers manage to meet after wandering over such a wildly circuitous route? Shimron and Frumkin think they know: The tunnelers were guided by communications from the surface, that is, by hammering on the bedrock above. Experiments conducted by Shimron and Frumkin demonstrated that communication by means of a hammer tapping on the bedrock above the tunnel could be an effective means of communication to a tunnel up to 50 feet below the surface and could be detected up to 80 feet. In short, “Acoustic messages between tunnel and surface must have been the dominant technique which controlled the complex proceeding underneath.” (Acoustic communication has been for centuries the method used for locating people trapped in mine catastrophes and earthquake collapses.)

According to Shimron and Frumkin, the final course of the tunnel was not that initially planned by Hezekiah’s engineers. Even they, however, find the shift in direction taken by the two teams of tunnelers somewhat puzzling. The northern segment shifts from a general west direction to south. The southern section shifts from an eastward direction to north. Shimron and Frumkin speculate that when the initial excavation of the tunnel brought the tunnelers to the middle of the hill beneath an overburden of some 160 feet, well beyond the feasibility of sound communication, it became clear to the engineers that a meeting of the two teams would become difficult, if not impossible. A decision must have been made to change the course of each of the segments and shift the direction to the east where the overburden is shallow and where surface-to-underground communication by hitting the rock surfaces would be feasible.

According to Shimron and Frumkin, Hezekiah’s Tunnel is thus “the oldest accurately-dated long tunnel constructed without using intermediate shafts for the excavation work proper.” (One shaft-to-surface chimney does exist near the southern end of Hezekiah’s Tunnel, but the researchers have determined from marks on the wall that this shaft was not used for descending down from the surface and excavating in either direction.)

That Hezekiah’s engineers depended on acoustic sounding to guide the tunnelers is supported by the explicit use of this technique as described in the Siloam Inscription. The frequently ignored final sentence of this inscription provides further evidence: “And the height of the rock above the heads of the laborers was 100 cubits.”d This indicates that the engineers were well aware of the distance to the surface above the tunnel at various points in its progression.

The now-discarded karstic-dissolution-channel theory to explain the route of Hezekiah’s tunnel has deprived us of a “rather elegant adaptation of a natural feature.” But it has been replaced by an explanation that Shimron and Frumkin call “a major advance in tunneling technique.”

MLA Citation

Footnotes

Dan Gill, “How They Met: Geology Solves Long-Standing Mystery of Hezekiah’s Tunnelers,” BAR 20:04.

See Neil Asher Silberman, “In Search of Solomon’s Lost Treasures,” BAR 06:04.

Jo Ann Hackett, Frank Moore Cross, P. Kyle McCarter, Jr., Ada Yardeni, André Lemaire, Esther Eshel and Avi Hurwitz, “Defusing Pseudo-Scholarship: The Siloam Inscription Ain’t Hasmonean,” BAR 23:02.

Endnotes

S.V. “Jerusalem,” The New Encyclopedia of Archaeological Excavations in the Holy Land (Jerusalem: Israel Exploration Society, 1993), vol. 2, p. 710.

James B. Pritchard, Ancient Near Eastern Texts Relating to the Old Testament, third edition, with supplement (Princeton, NJ: Princeton Univ. Press, 1969) p. 88.

The most recent suggestion, by Amos Frumkin and Aryeh Shimron, is that zdh refers to a false echo as the two teams were trying to find each other. This accounts, in their view, for the hewing deviations.

Ruth Amiran, Qadmoniot 1 (1968), p. 13 (Hebrew). See also, Arie Issar, “The Evolution of the Ancient Water System in the Region of Jerusalem,” Israel Exploration Journal 26 (1976), p. 130.

Dan Gill, “Subterranean Water Works of Biblical Jerusalem: Adaptation of a Karst System,” Science 254 (1991), p. 1467.

Amos Frumkin and Aryeh Shimron, “Tunnel Engineering in the Iron Age: Geoarchaeology of the Siloam Tunnel, Jerusalem,” Journal of Archaeological Science 33 (1976), p. 227. See also Amos Frumkin, Aryeh Shimron and Jeff Rosenbaum, “Radiometric Dating of the Siloam Tunnel, Jerusalem,” Nature 425 (2003), pp. 169–171.

Hershel Shanks, Jerusalem—An Archaeological Biography,” (New York: Random House, 1995), p. 91. See also Ronny Reich and Eli Shimron, “Reconsidering the Karstic Theory as an Explanation of the Cutting of Hezekiah’s Tunnel in Jerusalem,” Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research 325 (2002), p. 75.