Dead Sea Scroll scholars have sometimes ended up badly— as drunkards or in asylums. There is no denying that Dead Sea Scroll research is a stormy and dramatic field, an uncommon mix of great scholarship and crackpot ideas, of collusion and scandal, of passion and intrigue. For six decades, this highly potent mix has proven irresistible to scholars and the public alike.

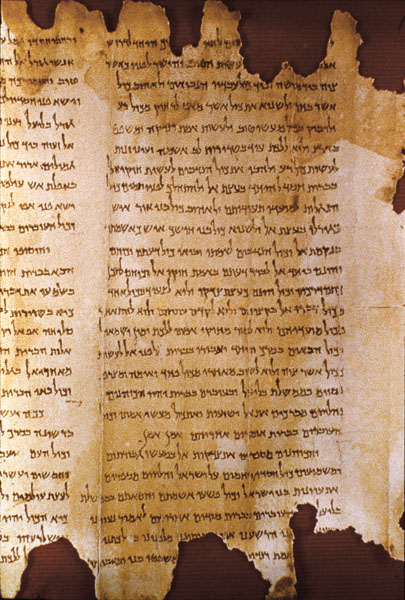

With their direct bearing on the origins of Christianity, the scrolls discovered near Qumran between 1947 and 1956 were quickly hailed as the most sensational archaeological finding of the 20th century.

The origins of Judeo-Christian civilization— the point of contact between Judaism and Christianity— is itself a fulcrum of intense interest. Ever since their discovery, the scrolls have held the potential of shedding light, in the words of the renowned Jesuit scholar Joseph A. Fitzmyer, “on the very matrix in which Christianity itself was born.”

Within the world of Judaism, too, expectations ran high: The scrolls held the promise of teaching us about the earliest stages of the development of halakhah (the body of Jewish law and ritual) and of comparing the oldest then-known Hebrew texts of the Bible with manuscripts more than a thousand years older.

To this day many puzzles surrounding the scrolls remain unsolved and fiercely contested. How are the scrolls related to Qumran, the site near the caves where the scrolls were found? Who wrote the scrolls? Who lived in Qumran? Much of the controversy is about whether or not Qumran can be described as the first monastery of the Western world. Seen one way, this question concerns a small, isolated, negligible-seeming sect of religious fanatics who believed themselves to be the Sons of Light against the rest of the world, who were the Sons of Darkness. Seen another way, the question touches on a set of ideas— purity, poverty, messianism, eschatology, predestination— that had a profound impact on the first Christians and is therefore of momentous cultural significance for the history of Western civilization.

The central theory in Dead Sea Scroll research holds that at the arid and remote site of Qumran, on the shore of the Dead Sea, lived a celibate religious community for some 150 years, within the timeframe of the two centuries spanning the beginning of the Christian era, contemporary with John the Baptist and Jesus of Nazareth. The theory further holds that this community belonged to the Jewish sect of Essenes, known to us almost exclusively from the Greek writings of the first-century Jewish historian Josephus Flavius (but also from the writings of his contemporaries Philo of Alexandria and Pliny the Elder), and that the sectarians of this community were the authors of the scrolls.

The mainstream theory thus makes a strong connection between the three key elements: the scrolls found in the caves, the nearby site of Qumran, and the sect of the Essenes. Israeli archaeologist Eleazer L. Sukenik attributed the scrolls to the Essenes very soon after the purchase of the first three scrolls from the Bedouin who discovered them in a cave near Qumran. The apocryphal account has it that he came up with this bold conjecture within the first few minutes of looking at the first scroll (The Rule of the Community) on the night of the historic United Nations vote to adopt the division plan of Palestine between Jews and Arabs (November 29, 1947). Many scholars immediately accepted this hypothesis, and it remains the consensus theory to this day.

But the theory has not remained unchallenged. Alternative theories are championed both for the origin of the scrolls and for the interpretation of Qumran. While differing widely, the alternative theories agree on one fundamental point: They sever all connection between the site and the scrolls.

The scholars offering the opposition theories are not overly impressed by the proximity of the Scroll caves to the site of Qumran (some of the caves are up to 2 km away), and they do not buy the mainstream interpretation of the site as a motherhouse of a religious sect. The principal alternative account offered by some of them for the origin of the scrolls is that they came from Jerusalem. Specifically, the claim is that the scrolls originated in a variety of Jerusalem libraries— possibly even the Temple library— and that they were rushed for safekeeping to the remote caves of the Judaean wilderness as the Roman legions were closing in on Jerusalem just before its final destruction in 70 C.E.

As for alternative interpretations of the site of Qumran, at least a dozen different ones have been tossed about. Among them: military fortress, aristocratic country villa, industrial plant, customs post, agricultural manor house, roadside inn and pottery factory. Common to these alternative interpretations is a picture of the site as fulfilling a mundane function, depriving it of any spiritual or religious character. All of them challenge the idea that the site served as a center for an ancient Jewish community and that a monastic, proto-Christian form of life was exercised in it. The controversy over the real nature and function of the site therefore has far-reaching implications for understanding a period that has had a profound impact on Western civilization.

All citizens in the republic of letters of Western civilization are justified in feeling that they have a stake in the unfolding story of research on the Dead Sea Scrolls and its findings— especially a person like me, my native tongue being the Hebrew language of the scrolls and my home being little more than a stone’s throw from the Shrine of the Book in Jerusalem, where the scrolls are on permanent display, and a mere 30-minute drive from the site of Qumran. Like so many others, I have found myself irresistibly drawn to the story of the scrolls and their mysteries. The more immersed I became, the more fascinating I found its details and the deeper my respect grew for the immense scholarship manifested in the research. At the same time, I became convinced of the need to resist the view that the story of the scrolls ultimately belongs to Qumranologists alone.

Over the years many crackpots, religious or scientific, have offered theories and solutions to the riddles of the scrolls, their provenance and their message. In response, defensive walls of suspicion have been gradually raised surrounding the discipline in general and the mainstream view in particular, separating “insiders” from “outsiders.” And these walls of suspicion, in turn, are responsible for the eerie yet pervasive feeling that in dealing with the Dead Sea Scrolls one is facing a sectarian phenomenon not only as regards the authors of the scrolls, but as regards their researchers as well.

Since I am not a Dead Sea Scroll scholar, I, too, may be suspect. My own credentials are that I come to this research as a professional philosopher trained, inter alia, in logic and the philosophy of science. My subject matter is not the scrolls themselves but rather the study of the scrolls— research about Scroll research. It is the inner logic of this research that interests me: Evaluating the competing theories, assessing the relationship between them and the evidence adduced in their support, asking questions relating to the confirmation and refutation of rival hypotheses, judging the validity of arguments.

From the perspective of the philosophy of science, the mainstream Qumran-Essene theory has, I believe, attained and maintained a peculiar status ever since its inception. The point is not that it dominates the field in the crude numerical sense that most of the researchers seem to subscribe to it, or at least to acquiesce in it; rather, it is that this theory functions as a default theory. This means that the Qumran-Essene theory is everyone’s “theory of choice”; it is one’s theory in the absence of good or conclusive reasons to switch to an alternative theory. In other words, unless and until an alternative theory wins you over, you stick with the Qumran-Essene theory, regardless of whether you might consider it less than compelling and regardless of how many faults you may actually find with it.

The subtle message being transmitted is that the threshold for switching to an alternative theory is more or less proof beyond reasonable doubt. Thus, in order for you to believe, for example, that Qumran was an agricultural manor house rather than a monastery, it is as if you have to ask yourself whether the evidence in favor of the manor-house theory is well-nigh compelling. If it is not, and as long as you are honest enough to acknowledge that it is not, you stay with the monastery theory by default.

This is certainly not the standard picture regarding scientific theories. At least on the level of principle it is not. Very roughly, the standard picture, in any particular scientific field, is of a marketplace of competing theories, each with its own set of evidence going for it and each corroborated to a certain degree by the evidence. The standard picture also has formulae and caveats about the way one’s degree of belief in a scientific theory should be updated when new pieces of evidence emerge, whether confirming or refuting. But a theory reigning over a scientific field qua “default option” is surely not— and cannot ever be— part of the normative view.

How did the Qumran-Essene theory attain that peculiar status?

I do not think the explanation lies in the speed with which this theory was initially proposed, promulgated and adopted. What might possibly account for its special status, as well as for its speedy spread, is a powerful combination of factors that helped bolster it— a combination not often encountered in the history of science. These comprise at least the following four factors: (1) a rich, previously unknown corpus of texts (the scrolls) that seem to suggest the Essene identification, (2) an enigmatic and unique archaeological site (Qumran) that seems to support it, (3) unusually charismatic scholars who propagated the theory in its early phase, and (4) a widespread eagerness on the part of the public at large to believe it. I briefly address these factors:

There is no question that the springboard for positing the Qumran-Essene connection are the striking points of resemblance between, on the one hand, what Josephus tells us about the Essenes and, on the other hand, the descriptions of the forms of life of the Scroll community in the very first scrolls to have been examined (most notably The Rule of the Community). Here is the voice of Sukenik’s son, the scholar-archaeologist Yigael Yadin: “We therefore have before us two alternative conclusions: either the sect of the Scrolls is none other than the Essenes themselves; or it was a sect which resembled the Essenes in almost every respect, its dwelling place, its organization, its customs.”1

Regarding the interpretation of the site of Qumran, we turn to the words of archaeologist Roland de Vaux, the great French excavator of Qumran, who conducted five seasons of excavations at the site between 1951 and 1956. Officially, he acknowledges that “lack of certitude hangs over all the archaeological evidence which we might be tempted to invoke in order to establish that the Qumran community was Essene in character,” and advances a rather modest claim of compatibility: “There is nothing in the [archaeological] evidence to contradict such an hypothesis.”2 That is to say, all the material finds in the ruins of Qumran are compatible with what the scrolls tell us about the Scroll community and its way of life.

Underlying de Vaux’s cautious, “official” text, however, there runs a subtext throughout his book. The theme of the subtext is that the archaeological evidence in and of itself “suggests to us that this group was a religious community [which] was organized, disciplined, and observed special rites”3— namely, an ambitious interpretation of Qumran as the motherhouse of a religious sect. It is surely in light of this ambitious interpretation that we must view de Vaux’s designation of one of the loci in the site as a “scriptorium” (i.e., a scribes’ copying room in a monastery) and of another as a “refectory” (a dining hall of a religious order)— both terms carrying distinct medieval Christian connotations of monastic life.

De Vaux, Yadin and Sukenik, all active in the very first years after the initial discovery of the scrolls, were scholars of immense personality and of distinct scholarly charisma. For the public, however, the eminent American writer and literary critic Edmund Wilson was equally important: The influence of his early series of articles about the scrolls in The New Yorker, as well as his best-selling 1955 book based on this series, cannot be overestimated.4

It was through Wilson that a large reading public in the English-speaking world was first introduced to the story of the Dead Sea Scrolls. Totally captivated by, not to say enamored of, de Vaux and Yadin, Wilson eagerly bought their Qumran-Essene version of the story of the scrolls, and helped entrench it in people’s minds for years to come. This surely accounts in large measure for the unique status of the Qumran-Essene theory as the grand “default theory” about the origins of the Dead Sea Scrolls.

The very connection of the scrolls with the Essenes has had an irresistible allure. By attributing the scrolls to the Essenes, one gets as close as one can to identifying and delineating the connecting link between Judaism and Christianity. This must have had a significant drawing power for many, just as it must also have held anxiety-producing potential for others, especially amongst the more conservatively orthodox Christians concerned to preserve the originality of the message of Jesus.

The Essene connection has thus proved capable of casting a powerful spell— religious, romantic and utopian. None of the alternatives to the Qumran-Essene theory could hope to rival it in attractiveness.

Attractive or not, alternative theories do exist, however, and they cannot be brushed aside on the strength of the attractiveness of the mainstream theory or of the charisma of its early proponents. Before addressing the alternatives, let me point out some weaknesses that inhere in the Qumran-Essene hypothesis. For example, regarding the Scroll-Essene connection, what are we to make of the fact that the term “Essenes” occurs not even once in the entire corpus of the scrolls?

Also, although striking points of resemblance exist between what Josephus tells us about the Essenes and what some of the scrolls tell us about the Scroll community, there are also striking discrepancies between the Scroll community and their beliefs, on the one hand, and Josephus’s descriptions of the Essenes, on the other.5 Thus, what are we to make of Josephus’s not mentioning the Essene settlement at the Dead Sea shore, if indeed the site functioned as an Essene center for more than a century? And what are we to make of the fact that, in describing the Essenes, he does not discuss predestination, a central tenet of the Scroll community?

And perhaps the most glaring omission: the Scroll community followed a solar calendar that set it apart from the majority of mainstream Jews, who followed a lunar calendar in the celebration of Jewish holidays, including Yom Kippur, the Day of Atonement. The Scroll community would thus be eating on what would be a day of fasting for other Jews (and vice versa). In his description of the Essenes, however, Josephus fails to mention this critical distinguishing feature of the religious and social organization of the Scroll community.

As for the archaeological side of the argument, Père de Vaux’s greatness as an archaeologist notwithstanding, there can be no question of his eagerness to interpret his archaeological finds in light of the texts of the scrolls, nor of his determination to establish Qumran as a center of a religious sect leading a communal life. To this putative “wishful archaeology” of de Vaux’s one might attribute quite a number of gaps, or of instances of rounding corners, in the overall archaeological argument.

As examples we may consider his treatment of the fortified tower (in a site of a supposedly pacifist community), of the finding of female skeletons in the Qumran cemetery (of a supposedly celibate community), as well as of so-called “gendered objects” (namely objects— such as a spindle whorl or beads— used or owned exclusively by women and hence attesting to their presence at the site).6 Other problems relate to de Vaux’s treatment of the precious-glass fragments found in the compound (of a supposedly ascetic community) and of the baffling case of the Copper Scroll.7

In recent years, especially since the 1990s, scholars such as Norman Golb, Robert Donceel and Pauline Donceel-Voute, Yizhar Hirschfeld, Alan Crown and Lena Cansdale, Michael Wise, Yizhak Magen and Yuval Peleg have vocally criticized the archaeological argument of the Qumran-Essene theory and offered alternative theories of their own. However, they have generally done a better job of poking holes at the mainstream theory and of pointing out its flaws and failings than at proposing coherent alternative theories with comparable explanatory power.

Does the fact that a large number of alternative theories have been offered constitute more of a threat to the mainstream theory than would be the case if there had been just one main rival theory? In my view, none of the alternative theories comes close to the theory of the consensus in its comprehensiveness and in its ability to account for the majority of the findings, and hence none succeeds in posing a serious threat to it. The trouble, however, is that precisely because they realize this, scholars of the mainstream believe they can get away with simply dismissing the rival theories. What they do not seem sufficiently cognizant of is that the motivation for each of the rival theories is a particular weakness or flaw in the mainstream theory— and that it is their task to come up with a plausible account for these weaknesses and flaws. The fortified tower at Qumran, the glass assemblage among the finds, the ambiguous nature of the pieces of plastered furniture in the alleged scriptorium (it was originally proposed that they were desks on which the scrolls were written, an interpretation increasingly challenged), the animal bone deposits found throughout the site, the industrial workshops and the Copper Scroll can all serve as examples here.

Because of the battering it has taken from the alternative theories, the Qumran-Essene theory has surely lost some of the headiness and the air of obviousness it had in the early years— but it has not crumbled.

I am inclined to believe that, while in principle it is possible, it is highly unlikely that “the true theory” has so far entirely eluded the mainstream Scroll scholars. I am also inclined to believe that their tendency to dismiss as illegitimate any alternative theory blinds them to the fact that their own theory has itself undergone changes over the years. The rival theories have not failed to leave their marks on the dominant Qumran-Essene theory, however much some of the mainstream scholars may deny this.

For example, mainstream scholars nowadays quite openly acknowledge that the scrolls reflect a variety of sectarian views (what we might call sectarian heterogeneity) and they are willing to concede that only some of the scrolls were written or copied at Qumran, and that many of the scrolls were brought to Qumran from elsewhere, possibly Jerusalem. Their understanding of what the epithet “Essenes” stands for, in terms of the Priestly origins, social class and religious doctrine of the sect, has also undergone evolution, as has the received view regarding orthodoxy vis-à-vis heterodoxy and sectarianism in the time of the Second Jewish Commonwealth. Views have changed, too, regarding the understanding of the number and nature of the mikva’ot (ritual baths) at Qumran and their significance. These and other modifications reflect considerable strides in research, including research by the “opposition.”

All in all, the Qumran-Essene theory has found ingenious ways to co-opt some of its challengers. Subtly adapted and re-described, it endures as the reigning consensus in Qumran studies. Barring dramatic new evidence that might yet come to light and cause a sea-change, this status of the Qumran-Essene theory, as far as I can judge, is just about right.

MLA Citation

Endnotes

Edmund Wilson, The Dead Sea Scrolls 1947–1969 (London: Collins Fontana Library, 1969); this is a revised and expanded version of W.A. Allen, The Scrolls from the Dead Sea (1955).

See, for example, Louis Feldman’s essay on Josephus in Lawrence H. Schiffman and James C. VanderKam, eds., Encyclopedia of the Dead Sea Scrolls (Oxford: Oxford Univ. Press, 2000).

For a discussion of gendered objects from Qumran, see Jodi Magness, The Archaeology of Qumran and the Dead Sea Scrolls (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2002), pp. 175–179.

Found in 1952 in cave 3, the Copper Scroll is an enigmatic anomaly. It differs from all the other scrolls in significant respects. It is chiseled into sheets of copper rather than written on parchment or papyrus; it is not a literary work like the others but comprises a listing of 64 locations at which vast amounts of gold and silver are supposedly hidden; its Hebrew style is late (Mishnaic); and it contains words of Greek origin. If the scroll belongs with the rest of the Dead Sea corpus— de Vaux ultimately came to believe that it does not— it seems difficult to reconcile the legendary treasures it lists with the ascetic nature of the Qumran community. Some scholars conjecture that it lists the hidden treasures of the Second Temple; others, however, believe that the Copper Scroll is a work of fiction or even a hoax. See Hershel Shanks, The Copper Scroll and the Search for the Temple Treasure (Washington, DC: Biblical Archaeology Society, 2007).