Spy Tales

012

013

Daily news reports from the Middle East are filled with tales of espionage, terrorism and counterintelligence operations. So is the Bible.

Indeed, some of the most dynamic biblical figures—Moses, Joshua, David, Delilah and Judith—either act as spies or command others to spy. It’s not surprising, when we recognize the Bible as the history of a people leaving, reentering, conquering, losing and returning to the land of Israel.

An understanding of military operations not only sheds light on how these 014shifts in Israel’s settlement history occurred, it also offers insight into some of the more unusual maneuvers of the Bible’s most cunning spies.

Although advances in technology have changed the methods, the underlying motivations for clandestine activity have remained the same since biblical times. Established rulers, whether ancient or modern, develop intelligence services for the defense of their countries, for political expansion, for the internal security of the state and their dynasties, and for the maintenance of control over their subjects. Leaders of occupied peoples have different intelligence needs: They run secret networks to foment rebellions, take back land and plan terrorist activities in the hope of liberating themselves. The Holy Land has witnessed both kinds of intelligence.

Our story begins with the latter sort. Moses and the Hebrews are stationed outside the land of Canaan. Before they can cross the Jordan en masse, they need intelligence about the unknown territory they are about to enter.

In Numbers 13, Moses briefs his reconnaissance team:

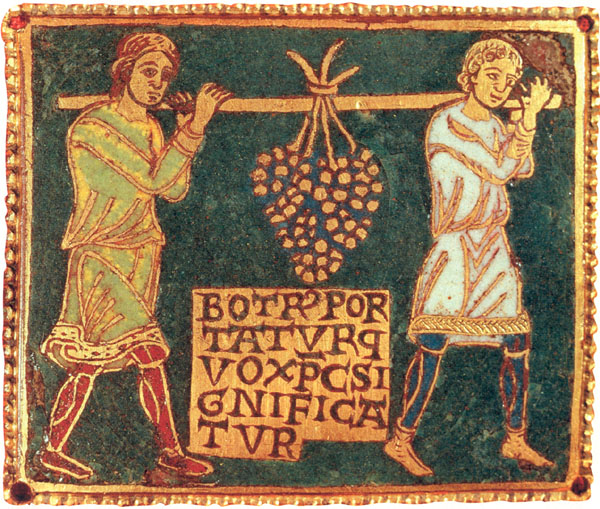

He said, “Go up through the Negev and on into the hill country. See what the land is like and whether the people who live there are strong or weak, few or many. What kind of land do they live in? Is it good or bad? What kind of towns do they live in? Are they unwalled or fortified? How is the soil? Is it fertile or poor? Are there trees on it or not? Do your best to bring back some of the fruit of the land.” It was the season for the first ripe grapes.

(Numbers 13:17–20)

The kind of intelligence Moses asks his men to gather—economic intelligence about the population and their agricultural capabilities, military intelligence about troop strength and fortifications—is fairly standard, even in today’s world of high-tech espionage and spy satellites.

And like any modern spymaster, Moses does not simply take his agents’ word for it; he wants hard evidence to back up their report—in this case, actual samples of the region’s fruit.

The spies heed Moses. After forty days, Moses’ 12 spies—they are in fact leaders of each of the 12 tribes—return with their produce samples and a detailed report on the land:

We went into the land to which you sent us, and it does flow with milk and honey! Here is its fruit. But the people who live there are powerful, and the cities are fortified and very large. We even saw descendants of Anak [the giant race of Nephilim] there. The Amalekites live in the Negev; the Hittites, Jebusites and Amorites live in the hill country; and the Canaanites live near the sea and along the Jordan.

(Numbers 13:27–29)

There is one aspect of this intelligence mission that at first glance seems counterproductive. Moses sends out 12 spies. And they aren’t just any 12 men, but the head of each tribe of Israel. If Moses had really wanted an impartial view of the nature of the land and the people of Canaan, he never would have sent out a bevy of political leaders; he would have sent out two or three skilled technicians.

Moses had good reason, however: He was not just spying out the land, he was also spying on his own men, trying to determine what sort of leaders the 12 would make. Were they strong and trustworthy? And, most importantly, did they trust God’s promise to deliver the Israelites into the Promised Land?

Here too, Moses meets with success. He finds that only Joshua and Caleb, representatives of the tribes of Ephraim and Judah, want to proceed with the campaign; the others are too fearful to invade. Clearly, they don’t believe God’s promise. As a result, God promises that all those who lack faith will die in the wilderness. Only their children, led by Joshua and Caleb, will settle in the Promised Land (Numbers 14:30).

Years later, after Moses dies and the Israelites are on the verge of crossing the Jordan River, another spy operation becomes necessary—this time to gather intelligence on Jericho, the first occupied location the Israelites will encounter as they cross into the Promised Land. The Israelites’ situation is different from what it was under Moses, and the kind of intelligence Joshua seeks is also different: He’s not so interested in food production and economics; he needs to know when and how to attack.

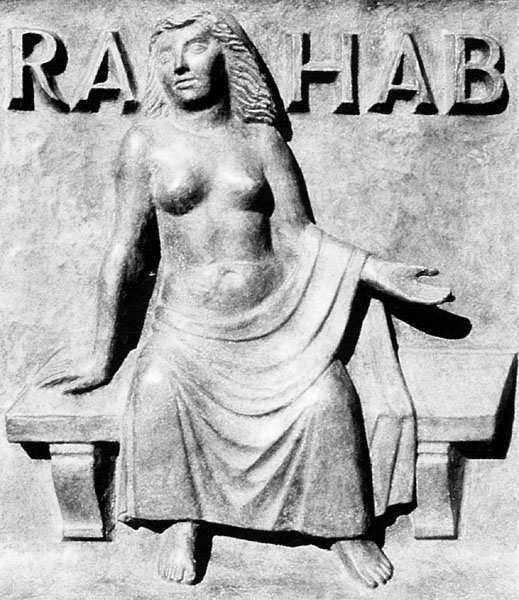

Joshua wastes no time in dispatching two spies to Jericho, who find lodging with a woman named Rahab who runs either an inn or a bordello in the city walls (Joshua 2:1).a Her location and occupation make her an excellent source for the kind of information Joshua wants: She has a good view of the city and a lively 015trade that involves intimate conversations with a great number of local men.

Rahab tells the spies that her town has already heard how the Israelites had passed safely through the Red Sea and had destroyed their enemies, the Amorites, east of the Jordan. Morale is low in Jericho, Rahab tells them. “Dread of you has fallen on us … All the inhabitants of the land melt in fear before you” (Joshua 2:8–9). After hiding out on Rahab’s roof, the spies return to Joshua with this report. This is just the kind of intelligence Joshua needed. Convinced that the proper psychological moment for the attack upon Jericho has come, Joshua sends the Israelites across the Jordan toward Jericho. For six days, they circle the city. On the seventh, the priests blow their trumpets, and the walls come a-tumblin’ down.

Joshua rewards Rahab for the intelligence and aid she gives the spies. When he captures Jericho, he spares her life and that of her family.

Joshua’s second spy mission in the Holy Land is not so successful, perhaps because this time he doesn’t have a good source like Rahab.

Having taken Jericho, Joshua sends agents to spy on Ai. The biblical account is brief:

Joshua sent men from Jericho to Ai, which is near Beth-aven, east of Bethel, and said to them, “Go up and spy out the land.” And the men went up and spied out Ai. Then they returned to Joshua and said to him, “Not all the people will have to go up against Ai. Send two or three thousand men to take it and do not weary all the people, for only a few men are there.”

(Joshua 7:3)

The spies’ recommendation proves disastrous. The 3,000-man force sent to take the city is routed and slaughtered.

016

We might fault the spies: Unlike the previous episodes, here the spies don’t bring back any material evidence to back up their conclusions; they don’t find a good informant like Rahab; they don’t provide any data confirming what they saw. They just tell Joshua what to do.

But, according to the Book of Joshua, it’s not just the spies’ fault: When Joshua prostrates himself in anguish, God informs him that the Israelites have sinned: One among them has hoarded some treasure from Jericho that was to have been reserved for the Lord. Once the offender, Achor, is called out and stoned to death, a new mission is launched against Ai; this time, purified, the Israelites succeed.b

This episode highlights an important aspect of biblical spy stories: God is the ultimate intelligence source. The best way for the Israelites to succeed militarily is not just through careful spying, but also 017through trusting in God and obeying his Law.

Obedience to God is not the only challenge facing the Israelites, however. They also have to watch out for double agents.

In the Book of Judges, Samson, the twelfth and last judge of Israel, falls in love with a woman named Delilah. Little does he know that she holds no real affection for him.

During the period of the Judges, the Israelites are finally and completely entrenched in the Holy Land. From a military point of view, it is an especially interesting period because it witnesses the struggle of a simple tribal society against a sophisticated foe that was often able to put up a fierce fight. Double agent Delilah—the paradigm for the myth of “woman as spy and seducer”—was just one weapon in the Philistines’ arsenal.

The Philistines have already had a few run-ins with Samson and lost when they contact Delilah and offer her 1,100 pieces of silver to find out the secret of Samson’s superhuman strength. Her methods are bold—perhaps even foolhardy. She asks Samson flat out, “Tell me the secret of your great strength and how you can be tied up and subdued” (Judges 16:6). One might think this would send Samson running, but he just lies to her: “If they bind me with seven fresh bowstrings not yet dry, then I shall become as weak as any other man” (Judges 16:7). The Philistines immediately supply Delilah with seven fresh bowstrings, and she ties him up while several Philistines hide in an adjacent room. Once he is tied up, she cries out, “Samson, the Philistines are upon you” (Judges 16:9). But of course, he snaps through the bowstrings and drives off his would-be killers.

Instead of exercising more caution with his double-crossing lover now that he knows her true colors, Samson continues with the game. When Delilah asks him a second time how he can be captured, he lies again: “If you bind me tightly with new ropes that have never been used, then I shall become as weak as any other man” (Judges 16:11). So Delilah finds new ropes and binds Samson with them—again with the Philistines hiding in the next room. When Delilah yells, “the Philistines are upon you Samson,” he snaps the ropes off his arms “as if they were threads” (Judges 16:12) and defends himself.

Delilah whines that Samson is making a fool of her with his lies (!), and asks for a third time: “How can you be bound?” Still into the game, Samson replies: “Take the seven loose locks of my hair and weave them into the warp [of fabric on a loom], and then drive them tight with the pin, and I shall become as weak as any other man” (Judges 16:13). So she lulls him to sleep, follows his recipe once again and then announces the arrival of his enemies. But once again, Samson has no trouble freeing himself from her trap.

Delilah’s nagging approach—asking Samson the same question day after day after day—might seem weak, but it works. He finally breaks down and confesses the truth. “No razor has touched my head because I am a Nazirite, consecrated to God from the day of my birth. If my head were shaved, then my strength would leave me, and I should become as weak as any other man” (Judges 16:17). Delilah senses that this time her lover has divulged his true weakness, so she contacts her Philistine handlers and tells them to come at once—and this time, to bring the money. She then lulls Samson to sleep on her knees. When, at her direction, a man sneaks in to cut the seven locks of his hair, she cries out, for the last time: “The Philistines are upon you Samson” (Judges 16:20). He wakes up confident and says, “I will go out as usual and shake myself free” (Judges 16:20), not knowing his strength has left him. The Philistines seize him and gouge his eyes out and then bring him down to Gaza. There they bind him with fetters of bronze and set him to grind corn in the prison.

It’s not the end of the story, of course. When the Philistines assemble together to offer a great sacrifice to their god Dagon, they bring out their Israelite prisoner Samson to “fight and make sport” for the Philistines. They fail to notice that Samson’s hair has been slowly growing back. With one last burst of strength, Samson pulls down the central pillars of the temple, killing himself along with several thousand Philistines. Perhaps he is releasing his pent-up frustration from being conned by a superb Philistine double agent!

018

The rise of the Israelite monarchy, following the death of Samson, witnessed a shift in military tactics and espionage methods. The Israelites were no longer outsiders trying to take control. Now their greatest worry was maintaining control.

Of all the kings, it is David who most vigorously pursued intelligence activities. David attained proficiency as a fighter and as a commander of regular forces while still serving in Saul’s army. Later, as leader of an outlaw band on the run from the jealous king Saul, David acquired firsthand knowledge, both as hunter and as prey, of guerrilla tactics. As king, David established a strong strategic base by creating a new mobile army, with mercenaries and an expanded chariotry, led by Joab. But he never gave up spying.

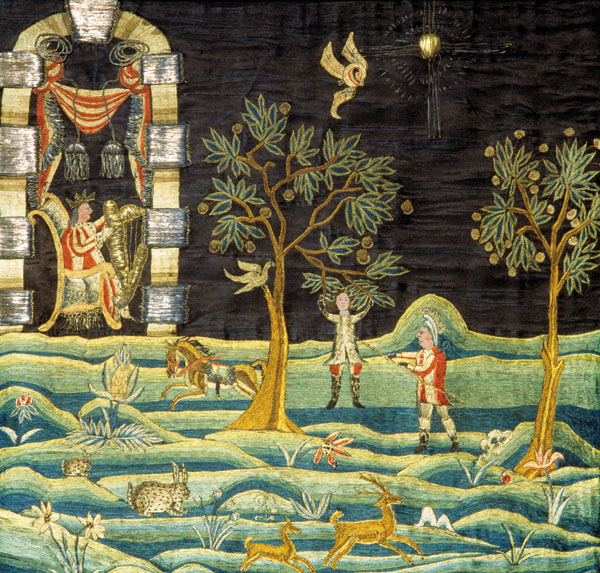

In his desperate attempt to hold on to the throne, David spied on his enemies, his subjects, even his family. In 2 Samuel 15, for example, David’s son Absalom is conspiring to take the throne from his father. David’s own counselor, Ahithophel, has fled the court and joined Absalom in Hebron, where he helps plan the coup. Absalom and Ahithophel are so successful, David is forced to flee Jerusalem. David’s friend and advisor Hushai wants to leave town with him, but David instructs him to wait in Jerusalem for Absalom. He asks Hushai to pose as a counselor to Absalom, and then to report back to David’s priests on all that is happening in Absalom’s court: “So whatever you hear from the king’s house, tell it to the priests Zadok and Abiathar. Their two sons are with them there, Zadok’s son Ahimaaz and Abiathar’s son Jonathan; and by them you shall report to me everything you hear” (2 Samuel 15:36).

What Hushai learns is that Absalom is planning to pursue David with 12,000 men and strike him 019down at night in the forest. Hushai not only sends the message to David, he also buys the king time by convincing Absalom to put off the attack until the morning. With this advantage, David is able to regroup and attack Absalom.

As David’s men chase Absalom through the woods, his splendid hair is caught in a tree, “and he was left hanging between heaven and earth.” David has begged his men to “deal gently with Absalom,” but Joab thrusts three spears into “the heart of Absalom.” Joab’s ten armor-bearers then surrounded Absalom “and struck him, and killed him” (2 Samuel 18:14–15).

All monarchs need an internal security apparatus to protect their throne from pretenders. All too often those pretenders are members of their own family. David’s spying saves his throne, but breaks his heart. On hearing of his son’s death, he cries: “Would I had died instead of you, O Absalom, my son, my son!”

The rise of the Israelite monarchy required accurate and timely intelligence. Unfortunately, intelligence was not enough to allow the monarchy to survive. In the late eighth century B.C., the Israelite kingdom fell under Assyrian rule, and then in the early sixth century B.C. the Judahites were sent into Exile by the Babylonians. When they returned to their lands under the Persians, they were forced to accept the leadership of foreign rulers for several more centuries.

It is in this setting that we find our last great spy: Judith, whose book is part of the Roman Catholic and Eastern Orthodox canon but is considered apocryphal by Jews and Protestants, perhaps partly because it is full of historical inaccuracies. The story begins with the Assyrian king Nebuchadnezzar sending his general Holofernes to punish various vassal peoples, including the Jews of Judea, who had failed to aid him in a recent war. Now, Nebuchadnezzar was actually the name of a Babylonian king who conquered the Assyrians as well as the Israelites. The author of Judith, by making Nebuchadnezzar an Assyrian, has created a composite bad guy out of Israel’s enemies. From a military point 041of view, this is the tale of a spy (Judith) from an occupied people. Her greatest weapon: disinformation.

Nebuchadnezzar’s general Holofernes ravages nations from Nineveh to Damascus and then sweeps down the Mediterranean coast toward Jerusalem, backed by an army of 170,000 infantry and 12,000 calvary. The Jews of Jerusalem resolve to resist. They tell the residents of the small mountain town of Bethulia to block the passes to the city. In retaliation, Holofernes seizes Bethulia’s water supply, with hopes this will force the city to surrender without a battle. After 34 days, the stores of water within the city are exhausted. The Bethulians tell the town leaders to surrender in five days.

News of the surrender plans reaches Judith, a widow who lives in austere retirement. She sends for the leaders of Bethulia and criticizes them for failing to trust in God. She promises them that she herself will achieve their deliverance within five days. Without hearing the details of her scheme, they agree to it and depart. Judith then prepares by praying and putting on the adornments she had laid aside after her husband’s death. She takes a single maidservant and a bag of clean (kosher) food and heads off to the Assyrian camp.

When she arrives at the Assyrian lines all decked out, the guards are impressed with her beauty. Nevertheless, they interrogate her: Where did she come from? 042Where is she going? She gives them a good cover story: She is a daughter of the Hebrews who is fleeing because they are about to be given up to the Assyrians. She wants to be conducted into the presence of General Holofernes to tell him how to win all of the hill country without suffering any casualties. Her plan of disinformation has begun. They buy it. The soldiers give Judith a contingent of 100 men who accompany her to the tent of Holofernes.

Judith causes quite a stir in the Assyrian camp when she arrives with her military escort. The crowd is so stunned by her beauty, they fail to realize just how effective such women can be as spies, decoys and disinformation agents.

Holofernes greets Judith and reassures her that no harm will come to her. And she reassures him that she can bring the Assyrians victory because the Jews have sinned by using first fruits and tithes intended for God alone; God will therefore deliver them up to their enemies. Once again, she is lying, but Holofernes, attracted as much by Judith’s appearance as by her simple plan, invites her to his table. He offers her his own wine and meats and shows her his silver vessels, but she rebuffs his overtures. She stays in the camp three days, leaving only to pray and bathe.

On the fourth day, Holofernes can wait no longer to see her, so he arranges a feast at which only his servants will be present. Judith agrees to come on the condition that she is allowed to eat her own food that she has brought in her now-familiar bag. She dresses up again and sits herself beside Holofernes on a sheepskin.

The critical moment arrives when the servants depart, leaving the spy and the general alone together. His excitement has caused him to drink more than he is used to, and he now lies helpless on his couch. Judith, calling on God for strength, makes her move: She takes his sword from above the bed and with two blows cuts off his head, which she puts in the bag carried by her maidservant waiting outside. The two leave the camp as though to pray, as usual—and escape to Bethulia.

Early the next morning, the people of Bethulia make a sortie, completely surprising the Assyrians, who try to rouse their general, but find him dead. They flee in panic and are pursued north toward Damascus while their deserted camp is sacked. The high priest Joakim comes in person from Jerusalem to bless Judith. The book ends by relating how Judith, the most pious of agents, dedicated her share of the spoils to God and remained a widow until her death at the age of 105. The land remained at peace throughout her life and thereafter.

Judith is not a military figure. She is not armed, nor does she fight with anything but disinformation. Unlike Delilah, her deception is for a good cause. She works alone, but the survival of the Jews is uppermost in her thoughts. She is as righteous as a secret agent can be.

From the entry of the Israelites into the land of Canaan to the return from Exile, one constant in their story is a superb use of intelligence. A small country with its back to the sea, often surrounded by hostile forces and more frequently than not occupied by huge military forces, the people of the Bible survived by their ability to keep an eye on their neighbors and their enemies and their sons. Expert intelligence and subtle disinformation earned them their independence more than once. We don’t know the names or deeds of most of the agents who camped out in the Judean hills in the dark, no doubt cold, watching and waiting and reporting back to their commanders about enemy movements. But we are reminded of them through the heroic tales of Moses, Joshua, David and Judith.

013Daily news reports from the Middle East are filled with tales of espionage, terrorism and counterintelligence operations. So is the Bible.

You have already read your free article for this month. Please join the BAS Library or become an All Access member of BAS to gain full access to this article and so much more.

Already a library member? Log in here.

Institution user? Log in with your IP address or Username

Footnotes

On Rahab, see Gary A. Rendsburg, “Unlikely Heroes: Women as Israel,” BR 19:01; and Frank Anthony Spina, “Reversal of Fortune,” BR 17:04.

On the taking of Ai, see Avraham Malamat, “How Inferior Israelite Forces Conquered Fortified Canaanite Cities,” BAR 08:02.