Stop the Charade: It’s Time to Sell Artifacts

042

043

I have been a professional archaeologist for almost 40 years, spending the better part of my career in the field or underwater, excavating and studying archaeological remains. I consider myself a devotee of the “New Archaeology”—more fascinated by data that illustrate ancient technology or ancient sea levels than by “treasure” such as gold coins, jewelry or even marble statues.

During all these years I have been burdened by one major problem shared with almost all my colleagues—the lack of financial resources to process and publish the finds properly.

For the last four years, I have directed a large-scale, year-round excavation project at Caesarea Maritima that has been lavishly financed as far as the fieldwork is concerned—the process of exposing archaeological strata. But when it comes to financing the scientific research and preparing the processed data for final publication, this, we are told, is not the government’s business: “Why should the government cover the cost of pursuing the professional career of a particular archaeologist?” I am told.

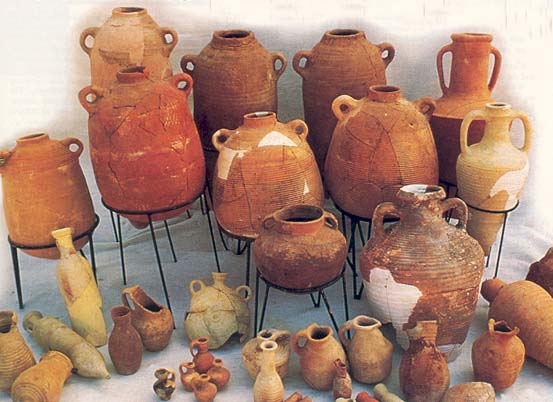

We already have over a million recorded items from the Caesarea Maritima project, most of which legally come under the designation “National Cultural Heritage.” This means that eventually these items are to be deposited with the Israel Antiquities Authority (IAA) and presumably placed in its storerooms. True, according to law, the artifacts are to be divided evenly between the IAA and the institute conducting the excavation. And unique items might be claimed for permanent display in the Israel Museum in Jerusalem. Other finds of more “local” significance might be displayed in a museum on the site or in the region, if there is such a museum. But, all in all, the number of these items will be very small. And only individual samples will be displayed, representing hundreds of other examples doomed to be endlessly and at great cost “curated” (stored), either at the IAA or the excavating institution.

The obligation to curate archaeological finds forever is well established in Israeli antiquities law. The vast majority of these items are simply potsherds with no market value whatever, but are regarded as the original materials on which the final report (rarely written) is based. The “better quality” artifacts—for example, complete and restored vessels, coins, oil lamps, juglets—number in the thousands.

What is the rationale for curating all these artifacts, saving them forever, supposedly in properly ventilated, climate-controlled storage space? The common answer is “We have an obligation to future generations; new technology might enable scholars in the future to extract additional information from these artifacts using techniques we have never dreamt of.”

By the same argument, we should keep all the excavated soil in airtight bags with every thin soil layer separately stored so that future researchers can learn more from the careful stratigraphic excavation we have conducted. Even now, we have the technology to search for DNA fingerprints in microfauna and food remains in such soil. As our methods improve, won’t we learn as much about urban life in ancient Caesarea from the ready availability of the excavated soil as from the thousands of oil lamps, already recorded, documented and published?

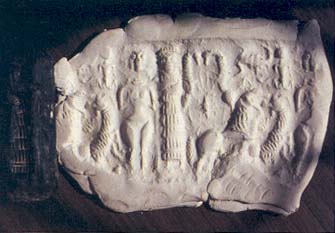

Or take a very rare cylinder seal from north Syria dating to the early second millennium B.C.E., found at Caesarea in some Byzantine fill. The seal is extremely interesting, but all it can really tell us about Byzantine Caesarea is that even then people already collected antiquities—something we already knew. Surely it should be properly published. But then what? Will it be displayed or stored in some museum? Truth to tell, it has only trivial importance for the archaeology of Caesarea.

To my mind, museums and collectors are the same, although UNESCO calls the former the “true keepers of cultural heritage” and the latter “the initiators of ‘treasure hunting.’” But both collect artifacts without regard to contextual provenance; both are scavengers of archaeological research. The only difference is that museums display some of their collections to the public. But most private collections of importance will eventually end up belonging to a museum, where the choice items will be displayed alongside artifacts from scientific excavations and even a few fakes from the antiquities market that have gone undetected.

BAR recently published an article about an unusual antiquities collector named Shlomo Moussaieff.a I agree with much of what Mr. Moussaieff says, but in one important respect I differ. “The archaeological community is stupid,” he is quoted as saying, because “they don’t dig in the right places.” He regards archaeological excavations simply as a means of finding important artifacts, either for museums or private collections. That is not the attitude of the professional archaeologist today. True, in the 19th 044century that was the attitude. Archaeologists then were contractors for museums and antiquities dealers, either funded by their own resources or sent by one of the major museums in the imperial or colonial western countries on missions to loot and strip the cradles of our civilization of their cultural heritage. If we would listen to Mr. Moussaieff, we would return to the ways of the 19th century. He would send us to the jungles of Central America and make us all Indiana Joneses.

I teach my students that our discipline studies the material remains of relevance to human activities in the past. For this purpose, a piece of charcoal might be of greater importance than a hoard of gold coins.

Nevertheless, I agree with Mr. Moussaieff that we are stupid—because the logic of our discipline does not include curating, storing and collecting artifacts after they have been properly processed, studied and published.

True, Mr. Moussaieff’s attitude has caused the authorities of the Mediterranean countries to react in a paranoid and emotional manner toward antiquities collecting. I can understand their paranoia: The contents of every Egyptian, classical, Near Eastern and Meso-American section of every major museum in Europe and North America is filled with loot that justifies such paranoia. But, still, the reaction of the authorities toward antiquities collecting makes little sense today.

There is a sensible resolution, however.

Unlike some (or most) of my colleagues, I do not consider all archaeological artifacts “sacred.” The public should have a right to see and collect the extraordinary artistic products of our ancestors and the special artifacts that reflect the history of civilization, especially written documents. Rock crystals and fossils are no less relevant components of the heritage of our planet; they are of the same nonrenewable character as every other ancient artifact. Yet, such items are sold freely at any souvenir stand and are exported by tourists with no restrictions or customs duties.

I believe it is imperative that Israel and other Mediterranean countries should now allow the sale of artifacts from legal archaeological excavations after proper scientific publication.

The following rules should govern these sales:

1. Every item must have a fully documented “Artifact Card,” in triplicate. (This is already demanded by the IAA regulations.) One copy should go to the government archives, a second to the archives of the excavating institution and the third to the purchaser.

2. Priority of distribution should be as follows:

(a) Unique items should go to the national museum.

(b) Other requested items should go to a museum on the site or to a public regional museum.

(c) Other requested items should go to study collections and/or the museum of the excavating institution.

(d) Other selected items should be stored for further research or future display (the latter for a planned museum).

(e) The rest should be sold on the antiquities market, through authorized antiquities dealers.

045

3. Every item sold should bear the excavation’s permit number, the registry number of the item, the year of excavation, basket number and locus number. The artifact card should also include reference to any publication of the item.

The revenue from these sales can be used by the excavating institutions and the government to sponsor further research—and for paying baksheesh to workers for turning over special objects found by them on the dig, such as gems, jewelry, coins and seals.

Of course the items sold in this way will be rather common types. The unique and special ones will be kept by the government (in Israel, the IAA), public museums and archaeological institutions. But as any antiquity dealer will verify, customers such as pilgrims to the Holy Land will pay ten times more for a certified genuine item with a real Biblical context, accompanied by scientific documentation, than for just another piece of antiquity.

My proposal will not change much for the large, prominent collectors like Mr. Moussaieff. They will probably continue their obsessive pursuit of unique items. However, the general atmosphere will change—from the present emotional and negative view of people who buy and collect antiquities as instigators of treasure hunts into the perception of them as potential benefactors and financial supporters of scientific research.

I am convinced that the implementation of this proposal will increase the public’s interest in archaeology. Eventually, the less hostile atmosphere toward collectors resulting from this proposal may induce other collectors to follow Mr. Moussaieff’s example in opening their collections for proper study and professional publication. Indeed, this used to be true when giants like Nahman Avigad and Yigael Yadin were among us. They often arranged for publication of, and sometimes themselves published, items in private collections. Perhaps because of their immense stature, they were unburdened by the “purist” attitude of some present-day scholars and members of editorial advisory boards of professional journals.

Having properly excavated and fully documented artifacts on the antiquities market will also present a new challenge to the forgery workshops. A few years ago, I saw a stone anchor offered by an antiquities dealer to the Maritime Museum in Haifa that bore a nicely inscribed Philistine (or other Sea Peoples) ship and some “Cypro-Minoan” signs. The anchor resembled the three-holed stone anchors of the 13th to 11th centuries B.C.E. and was probably genuine; but the decoration was not—yet marine encrustation covered both!

A sophisticated workshop in Gaza probably produced this specimen. There the authentic anchor had been “decorated” before being redeposited in the sea for a year or two to give it an authentic marine encrustation. This workshop (and others) does the same for fake oil lamps, juglets, glass vessels and clay figures, dumping them in lime for a period of time so that the authentic patina will indicate old age. An even more sophisticated workshop in Zurich is said to have produced several decorated pieces of red-figure Greek vessels using crushed ancient potsherds mixed with plaster. The paintings were executed by first-class artists using materials as close to those used by their ancient colleagues as current research can tell us.

None of this is surprising. Every collection, both private and public (museums), has its share of fake artifacts (including famous paintings and masterpieces purportedly of the 16 to 18th centuries). But selling genuine artifacts from legal excavations should decrease the market for fakes. At least we would know that the pieces purchased from these excavations—complete with archaeological context and provenance properly documented and verified—are genuine.

I have been a professional archaeologist for almost 40 years, spending the better part of my career in the field or underwater, excavating and studying archaeological remains. I consider myself a devotee of the “New Archaeology”—more fascinated by data that illustrate ancient technology or ancient sea levels than by “treasure” such as gold coins, jewelry or even marble statues. During all these years I have been burdened by one major problem shared with almost all my colleagues—the lack of financial resources to process and publish the finds properly. For the last four years, I have directed a large-scale, […]

You have already read your free article for this month. Please join the BAS Library or become an All Access member of BAS to gain full access to this article and so much more.

Already a library member? Log in here.

Institution user? Log in with your IP address or Username

Footnotes

“Magnificent Obsession,” BAR 22:03.