Sussita Awaits the Spade

The largest archaeological site on the east bank of the Sea of Galilee was once a thriving city of the Decapolis

050

051

Most stories in BAR are about sites that have been excavated. In fact, I can’t recall a single story about a place that hadn’t been extensively excavated. This story—about Sussita/Hippos, in the Galilee—may be a first.

Of course, a scholar must be very careful when writing in BAR. One little slip and someone will take him to task in a blasting letter to the editor that will be read around the world. So let me say at the outset, to qualify my opening statement, that the Israel Antiquities Authority did conduct a small salvage excavation at the site between 1951 and 1955 led by Claire Epstein.1 Much of the detailed information in this article comes from that excavation. Otherwise a spade has never touched the site, although in the latter half of the 19th century Gottlieb Schumacher made a thorough survey of the site,2 and the surface was again explored by the members of nearby Kibbutz Ein Gev in the late 1930s. The aerial photographs from the 1930s were a great help in reconstructing the plan of the city. And of course I also walked the site in connection with this article.

You might understandably ask: Why write an article about a site that has seen so little archaeological activity? The answer is manifold.

First, it will be interesting to see how much we can learn about a site even though it has not been extensively excavated.

Second, the Israel Antiquities Authority has plans to excavate the site and, in conjunction with the National Parks Authority, to restore it to some of its original splendor. Because of severe budgetary constraints, it may be some time before the excavation begins. When the excavation has been completed, however, we will have a basis of comparison to determine what we have learned from the excavation.

Third, Sussita/Hippos was one of the most important cities in the East during the Roman/Byzantine period, one of the towns of the famous Decapolis (the League of Ten Cities), and is today the most significant archaeological site on the eastern bank of the Sea of Galilee.

Fourth, Sussita/Hippos is hauntingly beautiful. No archaeological site that I know has a more impressive setting, perched on a lonely promontory a thousand feet above the diamond-reflecting lake below. Visit it in the light of the morning sun, see it by moonlight, from its ramparts watch the sun set over the Kinneret (the Hebrew name of the Sea of Galilee). See it in spring when wild flowers peek out of every crevice of the fallen 052architecture. Visit it in winter when all is bare, the wind blows off the lake, the sky threatens and the collapsed walls are most exposed. Is there anything more romantic than an unexcavated archaeological site strewn with ancient buildings, abandoned and destroyed? This alone is reason enough to write about Sussita/Hippos.

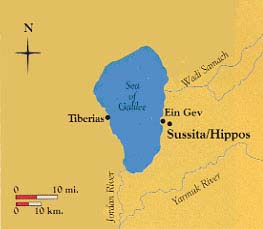

Located along the eastern shore of the lake is Kibbutz Ein Gev, founded in 1937. About a mile and a half east of Ein Gev are the remains of Sussita/Hippos, on the plateau of one of the many mountains that rise up to the Golan Heights east of the Kinneret. The site of Sussita/Hippos is surrounded on the north, south and northeast by deep, rocky gorges. On the west it falls even more steeply down to the lake. On the southeast, however, is a narrow ridge or saddle that connects the site to the Golan Heights on the east.

If you look at the site of Sussita/Hippos from an adjacent mountain, or, better yet, from the air, and follow the adjoining ridge, or saddle, to the east, the site looks like the head of a horse and the saddle, or ridge, looks like the long, outstretched neck of a horse. It is this configuration that gave the site its name for nearly a thousand years. The ancient Greeks, who apparently were the first to settle the site, must have been aware of this resemblance because they named the place Hippos (horse). When the Jews conquered the city, they translated the name to Sussita, “mare” in Aramaic. When the Arabs conquered it, they called it Qal’at el Husn, the “fortress of the horse.”

The summit of the mountain is a plateau of about 37 acres on which lie scattered the ruins of what was once a beautiful town overlooking the lake.

Our story begins—perhaps it will begin much earlier after the site is thoroughly excavated—about a century after Alexander the Great conquered and Hellenized much of the then-known world. After Alexander’s death in 331 B.C., his empire split in two—the Ptolemies in Egypt and the Seleucids in Syria shared this world. Over the centuries Palestine passed from one side to the other, occasionally winning its own independence. The first evidence we now have of organized habitation at Hippos indicates that it was founded by the Seleucids in the middle of the third century B.C., very probably as a frontier fortress against the threat of the Ptolemaic kingdom to the south. The settlement was located on a most strategic point, on the western approach to Gaulanitis (today’s Golan Heights). The site’s natural fortification and defense allowed it to serve equally as a fortress stronghold and as an effective frontierpost, controlling any movement to the east, both in time of war and peace. In about 200 B.C., the boundaries of the Seleucid kingdom were pushed down to southern Palestine, so Hippos lost much of its strategic significance but it retained its importance as an urban cultural center, with a social and political organization in accord with the principles of a Greek polis.

When the town was formally recognized as an official constitutional polis, it was renamed Antiocha, in honor of the head of the Seleucid kingdom, Antiochus the Great (III), although the old name Hippos was also officially used.

During this period, in the second century B.C., the city’s boundaries were extended in all directions. To the north and south, they were expanded up to the Wadi Samach and to the Yarmuk River. To the east, they were extended nearly 12.5 miles to include the perennial springs found south of Wadi Samach. The municipal territory of Hippos thus included many villages and large amounts of agricultural acreage, making it almost self-sufficient in food production. The fertile strip on the eastern shore of the lake, which was also included in its territory, further increased its agricultural base. At the same time it gave the city access to the Sea of Galilee for fishing, navigation and perhaps for military purposes. Hippos had, in effect, become somewhat of a city-state.

It was probably at this time that port facilities were first installed on the coast of the lake to serve the commercial and navigational needs of Hippos.

The progress of the city as a Hellenistic center was interrupted for a period of about 20 years during the first half of the first century B.C. Sometime between 83 and 80 B.C., the Judean king Alexander Jannaeus, who then ruled an independent fiefdom, conquered Hippos. According to the first-century A.D. historian Flavius Josephus (Antiquities of the Jews 14.75), Jannaeus forced Hippos’ heathen inhabitants to be circumcised and to accept Judaism. In 64 B.C., however, the Roman army entered the scene. The Roman general Pompey took the city from the Jews; it was then included in the League of the Ten Cities, the Decapolis, created by Pompey in the northern Jordan Valley and adjacent Transjordan. Each city in the Decapolis had jurisdiction over an extensive area. As a member of the Decapolis, Hippos enjoyed internal autonomy and could even mint 053its own coins. The population of Hippos welcomed Pompey with open arms.

About 35 years later, Hippos again became part of a Jewish realm. In 30 B.C. the Roman emperor Augustus gave Hippos to Herod the Great, who ruled it until his death 26 years later, in 4 B.C. After Herod’s death, Hippos was assigned by the Romans to the province of Syria.

During the First Jewish Revolt against Rome (66–70 A.D.), the Jews attacked Hippos and its Greek inhabitants, who retaliated by killing or imprisoning the Jews residing there.

The second and third centuries A.D. were the most prosperous years for Hippos, as they were for almost all the Greek cities in Roman Palestine and Syria. During these two centuries new public buildings were erected and a new town plan was laid in accordance with contemporary Roman standards of town planning. It is this town plan that can still be seen at the site. It is a Greco-Roman plan adapted especially for the East. The streets run at right angles and form characteristic rectangular insulae, or blocks. The main street, the Cardo, is still easily distinguishable. It runs the entire length of the city from east to west. It was paved with large basalt flagstones and was colonnaded on both sides.

Most of the town was occupied by public buildings and various civic institutions—a city hall (the bouleuterion), a theater, the central fountain (the nymphaeum), a bathhouse, temples, etc.

The nymphaeum, at the very center of the town, is still well preserved. It consisted of a huge subterranean cistern with vaulted roof and plastered walls over which stood a magnificent semicircular construction decorated with black basalt columns, white marble capitals and ornamental fountains. A few yards to the east on the main street, at one of the important intersections, stood the bathhouse for the recreation of the city’s inhabitants. The theater was probably just opposite the nymphaeum.

Zeus, Hera and Tyche were the principal deities worshipped in Hippos, and no doubt temples to these deities occupied prominent sites. Other Eastern deities, such as the Nabatean god Dushara, were probably also worshipped in a temple in Hippos, as they were in other Greek cities in the East. There was a synagogue, as well, serving the town’s Jewish community. (The remains of at least two other synagogues have been found in the territory of Hippos—at Apheka and at Um el-Qanatir.)

The only area of the town itself that seems to have been devoted to domestic use is a small quarter in the southwestern corner of the city. It is so small that it could have housed only a few hundred people. The principal living area was undoubtedly outside the city wall, in villages, some of which, such as Chasfyia and Caspein, Nab and Apheka, are mentioned in literary sources.

The buildings on the summit of the mountain were surrounded by a defense wall with towers set at strategic points. Both the wall and its towers are still well preserved. The wall follows the contours of the mountain, making use of the natural cliff wherever possible.

The city’s main street, the Cardo, bisected the town, 054as we have noted, in an east-west direction. The Cardo terminated in city gates at each end. The eastern gate leading to the saddle or ridge, is much larger and more magnificent. This gate was strengthened by a well-built circular tower nearly 30 feet in diameter erected on the rocky slope of the hillside. This well-fortified gate overlooked the narrow ridge and commanded the approaches of the main road leading into the city from the east. The western gate was much smaller and less impressive; it served the needs of inhabitants who cultivated the western terraces of the mountain.

Water was a major concern of the city. The rain that fell on the city itself was insufficient to meet the needs of Hippos’ expanding population. The problem was eventually solved by the construction of an aqueduct that brought water from springs almost 20 miles to the east from an elevation higher than that of the town. Passing over the eastern ridge, or saddle, the aqueduct carried the water by means of gravitation into the city, where it fell into huge subterranean cisterns, like the one built under the nymphaeum. This architectural and hydraulic achievement could convey about 1,500 cubic meters of water into the city each day.

Sections of the aqueduct can still be seen in situ at various points within the city as well as on the ridge. Each of the stone sections is square on the outside and 055round on the tubular inside. The sections were joined by sockets reinforced with plaster. Some of the sections have a vent hole on top to allow the escape of air bubbles and foam caused by the uprush of the water.

Agriculture, especially grain production, provided the most important economic base for the city. According to the Talmud,a the Jewish town of Tiberias was almost entirely dependent on grain imported from Hippos.3 Fishing, trade and transportation were next in importance.

Recently, some large port installations were discovered on the shore of the Sea of Galilee, south of Ein Gev.4 They consist of two jetties—a long one of nearly 600 feet and a short one of 130 feet. These two jetties, together with the sandy soil of the shoreline, formed a closed pool protected from the wind regardless of the direction from which it came. This port on the lake probably functioned as a marine suburb of Hippos, serving fishermen and traders and providing transportation to all. This maritime facility was no doubt a convenient communication artery as well, connecting Hippos with important land and marine routes. The income from this port added to the considerable wealth of Hippos and the port itself added to the town’s noteworthy prestige. With this income, Hippos could afford the grandiose buildings that adorned it and the complicated aqueduct project that brought it water. In this period Hippos became not only prosperous, but also a center of culture and learning. The first-century A.D. Roman writer Pliny praised Hippos by calling it “a pleasant town.”

Although Hippos was near centers of early Christianity, Christianity did not come to Hippos until the fourth century, at the earliest. By the fifth century, however, Hippos had become a bishopric. It was one of the sees of Palestina Secunda, under the ecclesiastical jurisdiction of the metropolis of Scythopolis (Beth-Shean).

By the sixth century the city had become entirely Christian. It was then that all of its temples were replaced by magnificent Christian basilicas, monasteries and other Christian institutions.

Within the walled city we can still see the remains of five churches, three on the northern side of the main street and two on the southern side. They occupied the most prominent sites within the city.

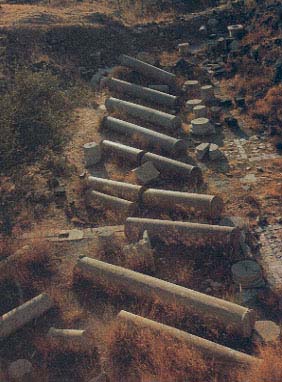

One of the churches, probably the cathedral, was partly excavated between 1951 and 1955. Located south of the Cardo and close to the nymphaeum, it consisted of a large complex that included a monumental basilica and a baptistry. The basilica contained a spacious atrium, surrounded on all four sides by a peristyle, or colonnade. The atrium was paved with large black basalt flagstones that contrasted with the white marble 056column bases and Corinthian capitals of the peristyle. The prayer hall was divided by two rows of monolithic granite columns into a central nave and two side aisles. The monolithic columns of differently colored marble and granite were as much as 16 feet high. They lie on the ground now, strewn like toothpicks. Close by are Corinthian capitals of pink and white marble which the columns once supported.

At the front of the nave were a large semicircular apse and two smaller side apses. The prayer hall, in contrast to the black paving in the atrium, was paved with different-sized colored marble slabs in an opus sectile pattern that formed various geometric designs. The apse was similarly paved.

The chancel, which encompassed the three apses, and the eastern section of the nave were separated from the rest of the prayer hall by a white marble screen, fragments of which have been found. One of the fragments contains a Greek inscription with the name of a certain priest, Procopius, who probably donated the screen to the church.

The abundance of glass tesserae found on the pavement of the church testify to the fact that at least some of the walls, if not all of them, were originally covered with colored mosaics. The lower part of the walls was lined with marble, as was customary in opulent Byzantine churches.

The baptistry, along the northern wall of the basilica, is also a triapsidal structure divided by two rows of columns into a nave and two aisles. This plan is more 057often associated with a mother church than with a baptistry annex. At the center of the baptistry’s main apse, a cruciform baptismal font was sunk into the floor and coated on the inside with pink plaster. The entire baptistry was paved with colored mosaics consisting of geometric patterns and floral designs.

In the center of each of the three apses was a cross of equal-length arms formed by two three-letter Greek words, both of which (in Greek) share the same middle letter: “light” (

In the floor of the nave and in the two aisles of the baptistry are Greek dedicatory inscriptions commemorating donors and including a date that corresponds to 591 A.D.

One especially interesting inscription refers not to the donor but to the church’s patron saints, Cosmas and Damianus, two Syrian brothers who were physicians. They provided their services to the poor without charge and were martyred in the last Christian persecution, during the reign of the emperor Diocletian, in the early fourth century.

The Arabs conquered Hippos without resistance in 637 A.D. The inhabitants simply surrendered to the Arab army after receiving a promise that they would not be harmed; and so it was. Life went on in Hippos for many years, though the days of radiance and glory were gone. As with all the Greek cities conquered by the Arabs in the East, Hippos lost its political and economic independence. Nor was it any longer a cultural center. Naturally the Arabs also discouraged Christianity. Almost immediately life in Hippos began to decay. Municipal institutions ceased to function, the 058economy was in shambles and the inhabitants began to look for alternative homes. In the early eighth century, Hippos still existed as a town and is listed in the newly founded administrative region of Jordan, but very soon thereafter it fell into obscurity.

In 747 A.D. an earthquake gave the already dying city the coup de grace. Its magnificent buildings, including the Christian basilicas, collapsed. The graceful columns still lie in ruins where they fell. Most of the domestic houses were demolished, never to be rebuilt. At this point the city was simply abandoned.

Over a thousand years later, in the early 19th century, the site was covered with weeds and dirt. The first modern visitors could barely see the town, much less identify it. Someday the archaeologist’s spade will bring Hippos back to life.

Most stories in BAR are about sites that have been excavated. In fact, I can’t recall a single story about a place that hadn’t been extensively excavated. This story—about Sussita/Hippos, in the Galilee—may be a first. Of course, a scholar must be very careful when writing in BAR. One little slip and someone will take him to task in a blasting letter to the editor that will be read around the world. So let me say at the outset, to qualify my opening statement, that the Israel Antiquities Authority did conduct a small salvage excavation at the site […]

You have already read your free article for this month. Please join the BAS Library or become an All Access member of BAS to gain full access to this article and so much more.

Already a library member? Log in here.

Institution user? Log in with your IP address or Username

Footnotes

Endnotes

See Claire Epstein, “Hippos,” in Encyclopedia of Archaeological Excavations in the Holy Land, vol. 2, ed. Michael Avi-Yonah (Jerusalem: Israel Exploration Society and Masada Press, 1976), pp. 521–523.