Synagogue Excavation Reveals Stunning Mosaic of Zodiac and Torah Ark

032

For two seasons in 1961 and 1962 (the second season lasted eight days into 1963) Moshe Dothan, then Deputy Director of the Israeli Department of Antiquities and Museums, directed the excavation of an ancient synagogue at a site known as Hammath Tiberias. Located on the shore of the Sea of Galilee, just 100 yards from the water and adjacent to some ancient hot springs, the site revealed one of the most beautiful, impressive and important synagogues in ancient Palestine.a The jewel in the crown was a magnificent mosaic of unusually high artistic quality with extraordinarily varied themes and motifs; the mosaic also contained inscriptions in Hebrew, Aramaic and Greek.

Dothan returned to the site for two short seasons in 1964 and 1965 to clarify some stratigraphic problems. Now, more than 20 years after the main excavation, the first volume of the final report on the Hammath Tiberias synagogue has appeared.b The report covers all the finds with the exception of the uppermost stratum.

This is too long to wait. But having said that, it must be 034quickly added that this is a magnificent volume, worthy of the site.

The range of Dothan’s learning is sometimes mind-boggling. Here is a mature scholar at the height of his powers. We expect him to be able to control the architecture, the pottery, the field methods, the ancient literary sources that give a historical context to the excavation, and the materials (archaeological and literary) relating to the development of the synagogue as a building and as an institution. In addition, however, Dothan can write authoritatively on the general history of the period, on the artistic aspects of the mosaics, on the epigraphy and linguistic characteristics of inscriptions in three ancient languages (Greek, Aramaic and Hebrew), and on the symbolism of artistic motifs, both Jewish and pagan—in short, a scholarly tour de force.

Dothan uncovered four strata at the site, numbered from I to IV from top to bottom. Stratum IV, the lowest, was reached in only a few places because the excavator did not want to endanger or undermine the strata above, especially Stratum II, which contained the superb mosaic. Few structural remains were found in Stratum IV.

What was found in Stratum IV, however, was in clear stratigraphic context and dated to the Early Hellenistic period (175 B.C.–75 B.C.). Historically, this covered the Seleucid and Hasmonean periods. The function of the structures from this stratum could not be identified, however.

In Stratum III (20 A.D.–135 A.D.), a large public building of some sort existed on the site. It was in fact much larger than the synagogue subsequently built above it. Although no architectural fragments were found in situ, two limestone column bases apparently came from this large public building. The building may have been a gymnasium or palaestra associated with the baths near the hot springs.

After the Second Jewish Revolt against Rome (132 A.D.–135 A.D.), Jews were excluded from Jerusalem and Judea. Many of them migrated north to the Galilee. Before then, Hammath had been home to a prominent Greek and alien population as well as a strongly Hellenized Jewish population. All three groups no doubt frequented the gymnasium. After 135 A.D., however, a new wave of Jews settled here.

In Stratum II, after the influx of Jews from the south, a synagogue was built on the site. Stratum II had two phases. In Stratum IIb, the first synagogue was built. Its plan was retained in the second synagogue in Stratum IIa. In Stratum IIa the walls were simply rebuilt and the entrances changed.

035

In addition, the first synagogue (Stratum IIb) had a mosaic that was replaced in Stratum IIa. Only small fragments of the earlier mosaic floor survived. Major segments of the Stratum IIa mosaic are intact, however, and these are in many ways extraordinary.

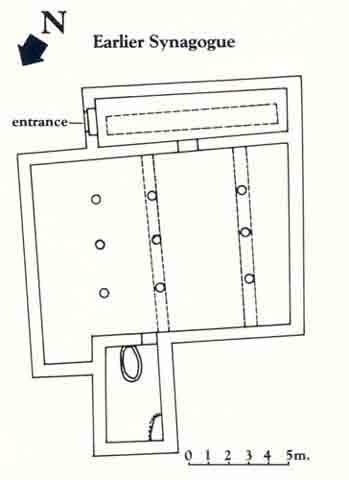

In Stratum IIb, the building consisted of three rooms: the main hall of the synagogue, divided into four parallel sections by three rows of parallel columns; a long narrow room south of the main hall, running along the length of the main hall to about 12 feet before its southeast corner; and a small rectangular room on the north of the main hall. The entrance to the building was through the narrow end of the long narrow room. There were probably three entrances from this long narrow room into the main hall. The small room to the north contained an oblong cistern, resembling a bathtub, which was probably used for storing liquids. The room may have been used for other storage as well and could have housed a stairwell leading to a second story of the main hall or to the roof.

During this phase of the synagogue, there was no permanent niche in the main hall for storing the Torah (or Scroll of the Law). It was apparently brought in for reading during the service in a portable container stored outside the main hall.

Worshippers would enter the main hall through one of the entrances in the southern wall and then turn around to face Jerusalem, as was customary in early Galilean synagogues without any permanent Torah shrine.

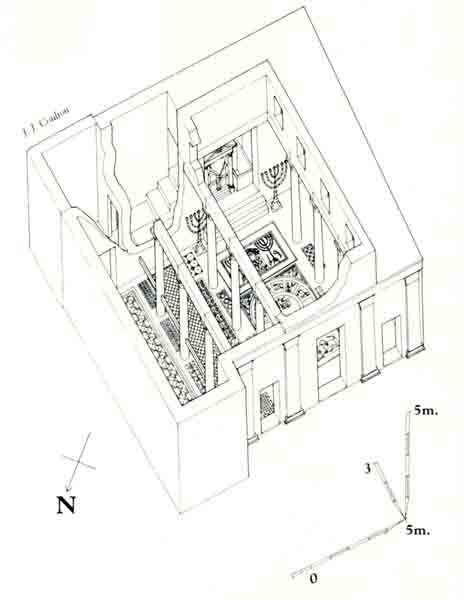

Later, after the introduction of a permanent Torah shrine, this shrine was oriented toward Jerusalem. In such synagogues, worshippers would enter through an entrance in the wall opposite the Torah shrine and, without turning around, would then be facing the Torah shrine and Jerusalem. That is what happened at Hammath Tiberias 036in the Stratum IIa synagogue.

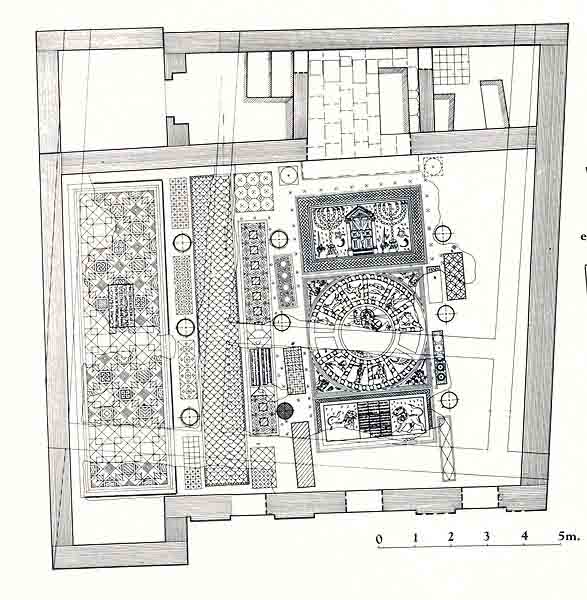

While large parts of the Stratum IIb synagogue were reused in Stratum IIa, the floor was raised about 15 cm (6 inches), and the building was reoriented. The long narrow room was extended to the full length of the southern wall of the main hall, but this extension effectively closed up the old entrance to the synagogue. Apparently three doorways were then cut in the opposite (northern) wall of the main hall. The room on the northern end of the main hall was removed.

The long narrow room on the south was subdivided into four small squarish rooms. In the new room on the eastern end of the long room, a new staircase may have led to the roof. The small room in the western end may have been used for ablutions—excavators found what may be a section of a water conduit. These small rooms may also have been used for storage. But the most interesting of these small rooms was the one leading to the widest aisle of the main hall—for this small room was probably turned into a housing for a permanent Torah shrine facing into the main hall of the synagogue.

The floor of this small room was about 70 cm (28 inches) higher than the floor of the main hall, so probably two wooden steps led up to the Torah shrine, with the threshold of the room serving as a third step. Dothan suggests that this Torah shrine was depicted in the mosaic carpet directly in front of it.

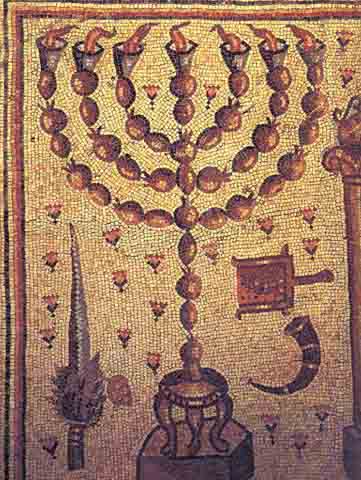

There in the mosaic we see the three steps leading up to the wooden Ark of the Law with its two paneled doors, which contains the Scroll of the Law. On either side of the steps are slender columns with schematic ionic capitals. Connecting the columns is a dentilated architrave that supports a triangular pediment containing a shell. A curtain in front of the Ark is rolled inward and tied in a knot to reveal the Ark.

The mosaic shows ritual objects on either side of the Ark—a palm frond (lulav) and citron (etrog) used during the Feast of Tabernacles (Succot), a ram’s horn (shofar) associated with Passover, and an incense shovel of the kind used in the destroyed Temple. Any doubt as to what this object is is allayed by the sprinkling of black, red and gray tessarae representing burning charcoal.

The principal ritual objects, however, are a pair of large seven-branched candelabra (menorot), each on its own pedestal. The stems and branches are composed of alternating pomegranates and oval knobs. The flames of the lighted wicks blow toward central stems, each supported by three visible feet of lion’s paws.

At the point in the floor of the synagogue where one of the menorot would actually have stood if it in fact stood next to the Torah shrine (as it does in the mosaic), the excavators found in the mosaic floor a simple small square in a circle. A similar square in a circle was almost certainly located on the other side of the Torah shrine, although this part of the mosaic floor has been destroyed. These squares-in-circles on the mosaic floor probably indicated the spots where the menorot were to be placed in the real synagogue, further suggesting that the mosaic in front of the Torah shrine depicted the actual Torah shrine in the synagogue.

Dothan associates the plan of the synagogue with the so-called “Galilean” (Dothan’s own quotes) or “early” synagogues. First collected in H. Kohl and C. Watzinger’s classic 1916 survey entitled Antike Synagogen in Galilaea, the Galilean synagogues are built as basilicas, each having three entrances in the southern facade and three rows of interior columns. Two rows of columns create a central nave and two side aisles. The third row of columns creates a back aisle.

At Hammath Tiberias there was no back aisle. The prayer hall contained a nave and two side aisles created by two rows of columns. But where we would expect to find the eastern wall of the basilica, we find a third row of columns, in effect adding another aisle on the eastern side of the basilica and giving the room a squarish shape. Dothan speculates that this additional aisle may have been for women, since the excavators found no evidence for a gallery or second story to which women may have been consigned. Dothan recognizes that the question of whether women were segregated in ancient synagogues or not is still an open one. A recent study by Bernadette Brooten entitled Women Leaders in the Ancient Synagogue, which perhaps appeared too recently for Dothan to cite, powerfully argues that men and women were not separated in ancient synagogues (see review in Books in Brief, in this issue).

The typical Galilean synagogue was heavily decorated on the outside, especially on the front facade. In later synagogues, the main focus of decoration was the mosaic floor. At Hammath Tiberias, clearly the main decorative focus was the mosaic floor, even in the first synagogue. And not a single decorated exterior stone with a 039structural function could be attributed to the first or second synagogue. To account for this so-called Galilean-plan synagogue with a mosaic floor, Dothan guardedly tells us that it is “one of the earliest [mosaics] so far discovered” in any synagogue. Thus, although the basic plan of the first synagogue (which had no permanent Torah shrine) can be associated with the early Galilean synagogues, the lack of exterior decoration and the presence of a mosaic floor suggest a date for the first Hammath Tiberias synagogue somewhat later than the “early” “Galilean” synagogues.

Later synagogues, although retaining an essentially basilical plan, eliminated the back row of columns (thus also eliminating the back aisle) and placed an apse in the back wall to house a permanent Torah shrine. In the early, Galilean types, the entrance facade faced Jerusalem so that upon entering, the worshippers turned around to face Jerusalem and watched a portable Torah shrine brought into the synagogue, perhaps through the middle of the three doorways in the entrance facade. In the later synagogues—with mosaic floors—the apse, housing a permanent Torah shrine, pointed toward Jerusalem so that worshippers no longer needed to turn around to face the Holy City.

Dothan postulates a “transitional” synagogue—the second synagogue (Stratum IIa) at Hammath Tiberias—with an additional open room at one end of the prayer hall to house an ark containing the Scrolls of the Law. This room eventually developed into an apse, which became a standard feature of later synagogues.

Dothan suggests that the “transitional” synagogue with the open room to house a Torah shrine first appeared about 300 A.D.—that is, during the late third or early fourth century. The second synagogue at Hammath Tiberias, with its open room to house the Torah shrine, is, according to Dothan, “one of the earliest” of the “transitional type” synagogues. (Interestingly enough, Dothan does not identify any other “transitional type” synagogues.)

Accordingly, Dothan dates the second synagogue at Hammath Tiberias—the “transitional” type—to the end of the third or beginning of the fourth century, a date he finds consistent with other evidence, including certain comparable geometric mosaics. The first synagogue at Hammath Tiberias, he says, was built in the early third century, probably during the reign of Alexander Severus (222–235 A.D.). Dothan finds support for this date in the pottery, in the coins, in what we know about the history of the period, as well as in the development of synagogue architecture. According to this typology, the “early” or Galilean synagogues would have been built in the late second and early third centuries.

The problem is that the most famous Galilean synagogue and the prototype—the jewel of Capernaum—is dated by the Franciscans who recently reexcavated this synagogue, not to the late second or early third century, but to sometime from the end of the fourth to the middle of the fifth century. (See my Judaism in Stone [Harper and Row, 1979], Chapter 5, and more recently, Strange and Shanks, “Synagogue Where Jesus Preached Found at Capernaum,” BAR 09:06.) If the Franciscan dating of the Capernaum synagogue is correct, this throws a monkey wrench into Dothan’s whole typology.

Dothan makes no mention of the controversy concerning the dating of the Capernaum synagogue. In a footnote, he tells us that the Galilean synagogues “are generally of the third century, disregarding the present controversy over the date of the Capernaum synagogue in particular and the dispute over the date of the other Galilean synagogues which this Capernaum controversy has generated.”

It is a difficult controversy to disregard, especially because several American scholars now agree with the Franciscans’ dating of the Capernaum synagogue, in light of recent highly controlled American excavations of Galilean synagogues. There is extraordinary scholarly disarray concerning the dating of ancient synagogues. Moreover, even the typology, especially the existence of the transitional type leading to the apse-plan synagogues, is controversial and open to doubt.

040

Clearly the dating of the Hammath Tiberias synagogue will be the subject of scholarly debate for years to come. And the pottery that is needed to establish the dates more securely is not abundant. Perhaps the dating will be clarified in the next volume.

Dating problems aside, the mosaic from the Stratum IIa synagogue is magnificent. Unfortunately, part of it was destroyed by a wall from a still later synagogue. We have already described the panel depicting the Torah shrine. We turn now to the subject of the central panel, which is puzzling, to say the least: It consists of the Greek god Helios surrounded by a zodiac.

Helios is depicted as a young man driving his solar chariot. The chariot itself, drawn by four horses, has been destroyed by the later wall. All that remains is Helios’s whip, the top of the mane of one of the horses (beneath the whip), and two horse hooves (on the other side of the wall). The horses soar over the clouds above the ocean, represented by streaks of blue and black at the bottom of the inner circle of the mosaic. In his hand Helios holds a celestial globe.

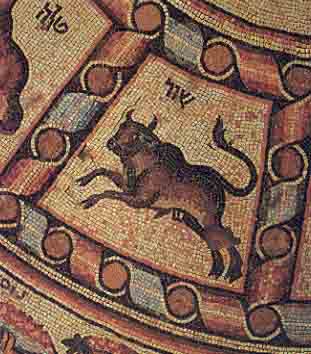

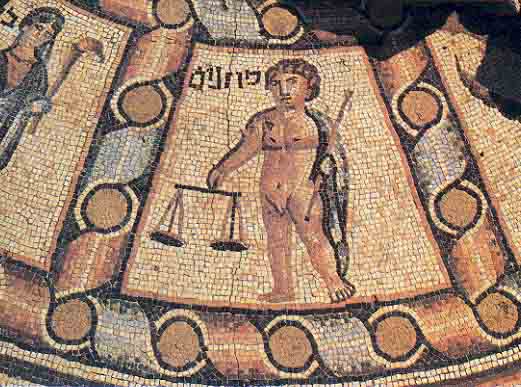

The signs of the 12 months are depicted in a band around the circle of Helios. The zodiac circle is enclosed in a square, the four corners of which are filled with delicate and subtle portraits of women representing the 043four seasons. Both the months and the seasons are arranged counterclockwise. Each of the zodiac signs and the season signs is identified in Hebrew.

In the upper left-hand corner of the zodiac, the humped bull (Taurus) gallops with its tail curled up toward its head. A powerful and dynamic representation, it is identified by the Hebrew word shor. Next to Taurus are the twins (Gemini), but only one is preserved. He is naked and apparently uncircumcised. At the bottom of the zodiac is Virgo holding a flaming torch. She wears a delicate white veil that falls behind her head and is draped around her torso, covering part of her striped tunic. Among the figures of the zodiac, only Virgo wears shoes. Next to Virgo is Libra, nude and holding scales. He too is uncircumcised. Perhaps this indicates that the mosaic was executed by a non-Jewish artist. The Hebrew word deli, identifying the sign for Aquarius (represented by a young naked male pouring water from an upside down jug over his left shoulder), has been flopped; that is, the word has been executed as in mirror writing. This further supports the suggestion that the mosaic was executed by a non-Jew who was unfamiliar with Hebrew.

The larger problem, however, is, What are a zodiac and a Greek god doing in a synagogue—in the central panel of the nave yet? The problem is compounded by the fact that the zodiac and Helios comprise a theme repeated in several ancient synagogues, of which Hammath Tiberias is only the earliest.

Dothan accepts the interpretation of the late Michael Avi-Yonah of Hebrew University—that these synagogue zodiacs, together with the signs for the seasons, were used in the synagogue to reckon time. Dothan reminds us that the final fixed calendar was not introduced publicly until about 325 A.D., presumably after the Hammath Tiberias zodiac was laid (but, alas for this theory, before all later synagogue zodiacs were laid). Dothan also stresses that the zodiac signs in this mosaic are identified in Hebrew even though Aramaic and Greek were the languages of common discourse. Thus, he argues, the zodiac calendar “was a kind of metaphor for the schedule of holy days and festivals … Moreover, the continued use of Hebrew strengthened the ties with the past and evoked a longing for the return to Jerusalem and the Temple.”

I confess I find this a bit far-fetched and overdrawn. Dothan himself records some difficulties with the theory. For example, of all the synagogue zodiacs, only at Hammath Tiberias are the signs for the months correlated with the seasons. To meet this objection, Dothan suggests that by the time the later zodiacs were executed, the calendar had been fixed for so long that these zodiacs were no longer needed and were simply ornamental and traditional. To me, this is not convincing. Moreover, as Dothan recognizes, the zodiac cannot be used as a calendar in the modern sense of the word. Another difficulty is that the Roman solar calendar cannot be reconciled with the Hebrew lunar calendar because the two are intercalated differently. The Hebrew calendar is intercalated with additional months in its leap years.

On the other hand, I don’t have any satisfactory alternative explanation for these pagan symbols that appear so frequently in ancient synagogues.

In Judaism in Stone, I offered the following:

“A belief in magic and superstition has often existed side by side with more elevated religious beliefs, including those of Judaism … A belief in the influence of the planets on the affairs of the world was part of the intellectual baggage of the time … Some third-, fourth-, and fifth-century Jews … did not see a necessary conflict between traditional Judaism and a belief that by paying attention to the zodiac they might improve their chances of having sufficient rain at the right time … For these Jews … there was no reason why their God could not work through the zodiac … For centuries, the calendar had been regarded as a reflection of godly regularity, and the zodiac may well have been a living symbol which many Jews adopted to represent this divine order” (p. 160–161).

More recently, Dr. Lee Levine of Hebrew University (in Ancient Synagogues Revealed, Israel Exploration Society, 1981, p. 9) observed:

“[There is] no room for doubt that certain Jewish circles of Byzantine Palestine did not regard Helios as merely a decorative element, or even as representing the power of God as creator of the universe. Rather, he functioned as a kind of super-angel capable of affecting one’s life.”

044

Obviously, we’re all still struggling for a satisfactory explanation of the zodiac-Hellos phenomenon in ancient synagogues.

The final mosaic panel in the nave of the Hammath Tiberias synagogue contains two lions flanking nine Greek inscriptions. The lions are symbols of Judah and Israel, watching over the names of the donors or founders mentioned in the inscriptions. The inscriptions, all written in Greek, contain names that are translated from Hebrew, Latin or Aramaic. Thus, for example, Gedaliah has become Maximos. Dothan reminds us that in the third and fourth centuries, after Caracalla’s introduction of the citizenship law, Jews were required to have Roman names.

A typical inscription is “Maximus vowing fulfilled [it]”—the functional equivalent of “Maximus fulfilled his pledge for a contribution to the reconstruction of the synagogue.” This is followed by a Greek word

A still later synagogue (from Stratum I) was built over the Stratum IIa synagogue containing this mosaic, but this later synagogue will be described by Dothan in a subsequent volume on the excavations.

In the third and fourth centuries, Tiberias was the spiritual capital of Judaism. The Sanhedrin convened here, and the official residence of the Patriarchs (presidents of the Sanhedrin) was established here. The Palestinian Talmud was compiled here. For these reasons, the Hammath Tiberias synagogue mosaic is all the more puzzling. This book beautifully presents a wealth of new information—some of it quite astonishing and perplexing—to illuminate this fascinating period. We are all grateful to Professor Dothan.

For two seasons in 1961 and 1962 (the second season lasted eight days into 1963) Moshe Dothan, then Deputy Director of the Israeli Department of Antiquities and Museums, directed the excavation of an ancient synagogue at a site known as Hammath Tiberias. Located on the shore of the Sea of Galilee, just 100 yards from the water and adjacent to some ancient hot springs, the site revealed one of the most beautiful, impressive and important synagogues in ancient Palestine.a The jewel in the crown was a magnificent mosaic of unusually high artistic quality with extraordinarily varied themes and motifs; […]

You have already read your free article for this month. Please join the BAS Library or become an All Access member of BAS to gain full access to this article and so much more.

Already a library member? Log in here.

Institution user? Log in with your IP address or Username