048

One morning in February, about nine o’clock, I was having breakfast. On my left Ulf and Helena were speaking German; on my far right Ami, Aaron and Tami were discussing the day’s work in Hebrew; in front of me Amanda from South Africa was listening to Michael’s Australian version of English; and at my right elbow Seong Kim was muttering in Korean as he tried to open a can of fish with my Swiss Army knife. This was not the breakfast to which I was accustomed at my boat shop in Marblehead, Massachusetts. I was now at a tell in Beth-Shean, Israel, working as a volunteer excavating a Late Bronze Age Canaanite temple.

My adventure started about a year before when I saw a listing of digs and volunteer opportunities for the coming season in BAR. The first listing was for Beth-Shean and was already in progress. However it also mentioned they would be digging again in the fall and winter. This got my attention for several reasons. First, history has always been one of my interests, and I had often wished I could work on a dig. Second, winter is the slack season in my shop, and I could spare the time. And third, I had been to Beth-Shean before when my wife, Susie, and I joined a ten-day bus tour of Israel and Egypt. One short stop included the Roman theater below the tell.

I wrote to Professor Amihai Mazar, director of the excavations, and after an exchange of letters during the summer and fall I learned the dig dates had been set for January 21 through March 1. This was great—now instead of just two weeks in January, as I had expected, I would stay for the whole six weeks and experience the start and finish of the year’s work on the site.

An additional attraction was the accommodations. We were to stay at Kibbutz Kfar Ruppin. The kibbutz is in the Jordan Valley on the Jordan River (the border between Israel and Jordan).

After a flight to Tel Aviv, a bus ride and two days in Jerusalem, I met Bob Mullins of the excavation’s staff and a van full of other staff, volunteers and equipment. It was a very early and bumpy ride in the van, but in about an hour and a half we arrived at Kfar Ruppin. There we met our host; “Czech” was to be our principal contact with the kibbutz. He was an older man, retired from the Israeli army and now a member of the kibbutz. He spoke excellent English and was full of jokes and stories about his life, the kibbutz and his experiences in the army. He was the man to see about laundry, scrip for the kibbutz store, telephone tokens and any of the other things needed to make our stay comfortable. Dana, a young woman who worked in the kitchen, was our other contact. She saw to it that we were fed properly, and as our hours were different from most of the rest of the kibbutz, we kept her busy. The food was very good, with more varieties of vegetables than I was used to, supplemented by meat, poultry or fish. The food was well prepared and there was plenty of it.

We were assigned two houses that had previously been used as children’s houses. One was for the staff to live and work in, and the other was for the volunteers. We were four in each small room, with iron cots and foam mattresses and not much provision—or space—for hanging clothes, but it was better than some of the barracks in which I had lived when I was in the navy. Most of the volunteers were in their early twenties and were happy with the accommodations.

Czech also saw to it that we all got a tour of his kibbutz, of which he was obviously very proud. We saw the fish ponds, which were harvested for fish in the spring and used as a reservoir for irrigation water in the summer. As the Jordan Valley is a natural flyway for birds migrating from Europe to Africa, these ponds attracted a large number and variety of birds. For a bird watcher this place would be paradise. We traveled on the army-built road along the Jordan River and saw the defenses against infiltrators. Many of us were surprised at how small the river was after hearing about it in story and song all our lives. We also saw the kibbutz plastics plant, where they made toys, and the farm with its cows and date palms.

We had several talks about the kibbutz, its history and its lifestyle. Czech told us about one woman who wanted to join the kibbutz. Her skills were needed, but she did not want to give up her horse. On the kibbutz, individuals were allowed to own dogs but not automobiles. The question before the membership committee was, “Is the horse more like a dog or a car?” The answer: “It’s a dog.” The woman joined the kibbutz.

Our day started at 5:15, well before sunrise, and by 5:45 we were in the dining hall for a quick cup of hot tea or coffee and bread. Mostly we prepared our breakfast, which we were to eat later on the tell. We gathered bread, vegetables, sliced meat and cheese, and fixings for sandwiches in plastic bags. 049By 6:15 we were boarding the bus for our ride to the tell, about five miles up the road in the town of Beth-Shean.

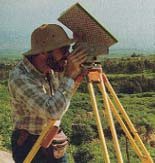

The first chore was to carry tools and buckets up the 81 steps to the top of the tell and to catch our breath. Luckily, there was plenty of help, and we only had to make one trip each. We were divided into teams with a supervisor for each team. My team leader, Tami, was very patient with us; she explained what she wanted done and how to do it. She also looked carefully at each find we made and told us what it was. Most of the work consisted of digging a small area about 10 square feet, working down an inch or two at a time until we discovered something of interest or until we found a floor. A floor could be a harder packed layer of dirt, an area of flat flagstones or a layer of plaster. I became very good at cleaning off plaster floors. We also found many pieces of pottery and bones, which we were instructed to save. We each had a bucket with a tag identifying the location of the finds within it into which we put pottery sherds, bones and other finds. These were later washed and sorted by Ami, the director, and the staff. The important pieces were saved and most of the unusable sherds discarded. Some of the better discards were kept by the staff and volunteers for private study collections. Sometimes there were enough sherds of a pottery item to make it worth reconstructing. In that case, all the sherds in that bucket would be labeled for restoration and set aside. The bones were put into paper bags, labeled and sent back to the university for further study.

At 9:00 a.m. we stopped for half an hour for breakfast. By this time the sun was up, and it was getting warm; the jackets that had seemed so cozy a couple of hours earlier were off, and all kinds of sun hats were on. Ami sometimes extended this break with a tour and lecture on our dig, or had Bob Mullins take us around the Roman ruins being excavated at the base of the tell. Then it was back to work again until a 15-minute rest break at noon and more work until 1:15, when we packed up our tools, covered work areas with plastic sheets against the rain and went down the tell to get our ride back to Kfar Ruppin.

Our dig consisted of three Late Bronze Age temples built on top of each other. One aspect of our work was to find the relationship between them. The director and the staff spent most of their time drawing what we were uncovering and measuring the areas and relationships between them. When it was decided we had dug enough, Ami would tell us to “clean up the area,” and then he would take a series of pictures. My most exciting find was the Cucumber Goddess, a 6-by-1-inch cylindrical stone, naturally rounded at each end, with what appeared to be two eyes, a hairline and an inscribed belt. Other interesting finds included two bronze arrowheads, a bronze kettle handle, pieces of alabaster containers, cooking and storage pots, a small stone dove and many other items.

We had lunch at 2:00 p.m. and then were free to shower, change clothes, help sort pottery with the staff or just relax until supper. The staff spent the afternoons and some of the evenings sorting, identifying and dating pottery sherds, and working on the notes and drawings that they had started during the day. The day ended with the evening meal at the dining hall at 7:00. With a 5:15 wake-up call we usually went to sleep early.

The weekends (from Thursday afternoon until Sunday morning at 6:30) also were free. I spent some of the time resting at the kibbutz and two weekends in Jerusalem with others from the dig, going to museums and exploring the Old City. Twice I rented a car and went to Haifa, Akko and other places in the Upper Galilee. Because it is my trade, I was especially interested in seeing the 2,000-year-old boat at Kibbutz Ginosara and the Maritime Museum at Haifa.

Volunteering on the dig has been one of the most interesting times of my life. While I may never do it again, I would highly recommend the experience to anyone interested in history and in meeting people from other parts of the world who have the same interests.

One morning in February, about nine o’clock, I was having breakfast. On my left Ulf and Helena were speaking German; on my far right Ami, Aaron and Tami were discussing the day’s work in Hebrew; in front of me Amanda from South Africa was listening to Michael’s Australian version of English; and at my right elbow Seong Kim was muttering in Korean as he tried to open a can of fish with my Swiss Army knife. This was not the breakfast to which I was accustomed at my boat shop in Marblehead, Massachusetts. I was now at a tell […]

You have already read your free article for this month. Please join the BAS Library or become an All Access member of BAS to gain full access to this article and so much more.

Already a library member? Log in here.

Institution user? Log in with your IP address or Username

Footnotes

See Shelley Wachsmann, “The Galilee Boat—2,000-Year-Old Hull Recovered Intact,” BAR 14:05).