022

It has long been a truism that the Bible is the most-published book in the history of Western culture. But for almost 250 years, from about 1275 to 1525, Books of Hours (illuminated prayer books whose heart is a series of prayers devoted to the Virgin Mary) were the medieval best sellers.

During this period the Book of Hours was the book most frequently commissioned by both the aristocracy and the middle classes. On the pages of Books of Hours the best artists created the most beautiful pictures, and the prayers on these pages offered the reader an intimate conversation with one of the most 024important people in medieval Christian religious life, the Virgin Mary.

The Book of Hours evolved from the clerical breviary. Medieval clergy were required by the Roman Catholic Church to recite daily the Divine Office, a complicated series of prayers that changed every day. Priests, monks and nuns fulfilled this obligation by singing their prayers from large choir books called antiphonaries or, most often, by reciting from prayer books, breviaries, which contained the prayers, hymns, psalms and readings of the Divine Office.

With increasing wealth and education, the late medieval laity began to covet both the clergy’s prayers and its books, particularly the breviary. Lay men and women also envied the clergy’s direct relationship with God and sought a series of prayers like the clergy’s, but less complicated. They sought a book like the breviary but easier to use and more pleasing to the eye. The Book of Hours became that book.

Another factor behind the emergence and explosive popularity of the Book of Hours was the growth of the cult of the Virgin Mary in late medieval times. It was in her honor that hundreds of Gothic cathedrals were erected in this period. The prayers in, a Book of Hours allowed an individual to establish a personal relationship with Mary, the mother of God, and with the saints, without the mediation of clergy.

In medieval piety, the Virgin was regarded as a divine intercessor—someone, who could be counted on to speak with God on behalf of a pious sinner—a powerful concept in an age ravaged by plague and obsessed with death and damnation. Similarly, saints were regarded rather like “celestial lawyers” working on behalf of their “clients” on earth.

But it is the art contained in Books of Hours—gloriously detailed paintings known as illuminations, which decorate the texts of these handwritten books—that best explains their popularity. From the late 13th century to the early 16th century, the greatest painters of the era produced their best work on the pages of Books of Hours rather than on panel or fresco. Painters were commissioned to execute the finest decorations with the costliest materials, such as gold, silver and lapis lazuli.

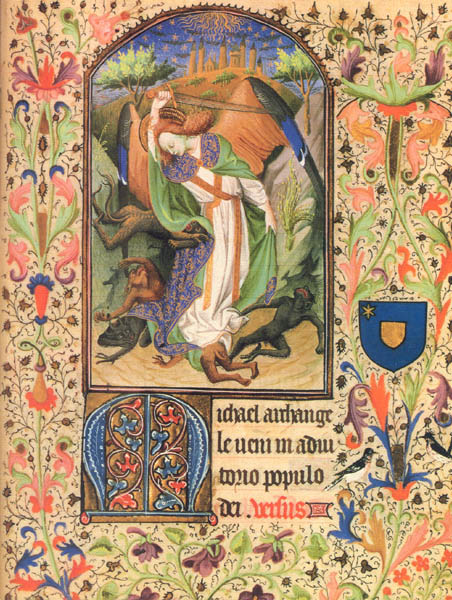

Although the content of a Book of Hours 025varies from volume to volume, most Horae (the Latin word for hours) consist of eight parts, each of which exhibits its own rich iconography: 1) a Calendar; 2) the four Gospel Lessons; 3) the Hours of the Virgin; 4) the Hours of the Cross and Hours of the Holy Spirit; 5) two prayers to the Virgin known as the “Obsecro te” (I beseech you) and “O intemerata” (O immaculate Virgin); 6) Penitential Psalms and Litany; 7) the Office of the Dead; and 8) numerous Suffrages (prayers to individual saints). (See photo of illumination depicting “St. Michael Battling Devils”)

The Book of Hours can be compared to its architectural counterpart, the Gothic cathedral. The structure of a Book of Hours is like a “Notre Dame” that can be held in the hands. Instead of portal sculpture depicting seasonal labors and zodiacal signs, stained glass windows illustrating the lives of the saints, and a cemetery, the Book of Hours had a Calendar, Suffrages and an Office of the Dead. But the “high altar” of any Book of Hours—around which all the other prayers were centered, acting as mere supporting elements—was the Hours of the Virgin.

The Hours of the Virgin originally formed part of the clerical breviary and were lifted from it to form the centerpiece of the Book of Hours. The Hours of the Virgin are made up of eight canonical “Hours.” Each Hour contains psalms and other prayers to the Virgin that were to be recited at different times of the day: Matins and Lauds (day-break), Prime (6 a.m.), Terce (9 a.m.), Sext (noon), None (3 p.m.), Vespers (sunset) and Compline (evening). These prayers sanctified the entire day, dedicating it to the Virgin Mary.

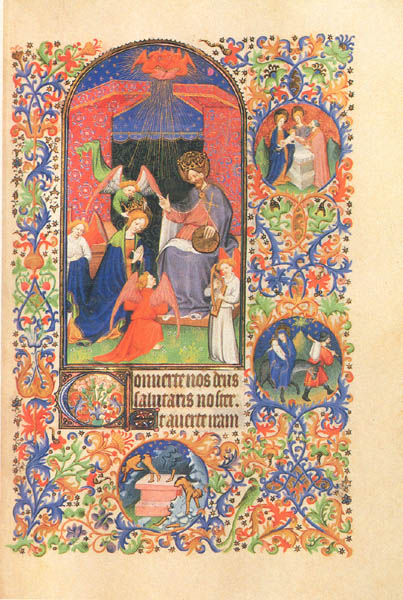

At each Hour the devotee, assisted by the illustrations, meditated on one of eight episodes from the early life of Christ. The cycle of miniatures, forming the pictorial core of the Book of Hours, included the Annunciation, Visitation, Nativity, Annunciation to the Shepherds, Adoration of the Magi, Presentation in the Temple, Flight into Egypt and, as a grand conclusion, the Coronation of the Virgin. (See photo of “Coronation of the Virgin”)

By praying from a Book of Hours a lay person enjoyed privileges usually reserved for the clergy. Saying the Hours of the Virgin with complete absorption could be like entering a cloister where priests, monks and nuns, charged with reciting the Divine Office, “prayed without ceasing” (Luke 18:1).

Among the supporting texts that accompany the Hours of the Virgin, several are particularly interesting.

The Calendar, the first section of a Book of Hours, is a list divided into 12 months of 365 saint’s or feast days. In the Middle Ages, each day of the year commemorated an event in the life of Christ or of a saint— usually the day he or she died—and it was this religious significance that gave each day its real meaning. The illustrations for and Calendars, though, are not of a religious nature. Instead, they usually contain scenes of peasant labors and aristocratic leisures of the year, picturing medieval daily life according to the season.

The four Gospel Lessons, readings from 027the Mass of the feasts of the Annunciation, Christmas, Epiphany and the Ascension, are usually illustrated with portraits of the four evangelists—Saints Matthew, Mark, Luke and John—placed at the beginning of each reading. The evangelists are often pictured in the company of their traditional symbols: the eagle for John, the ox for Luke, an angel for Matthew and the lion for Mark.

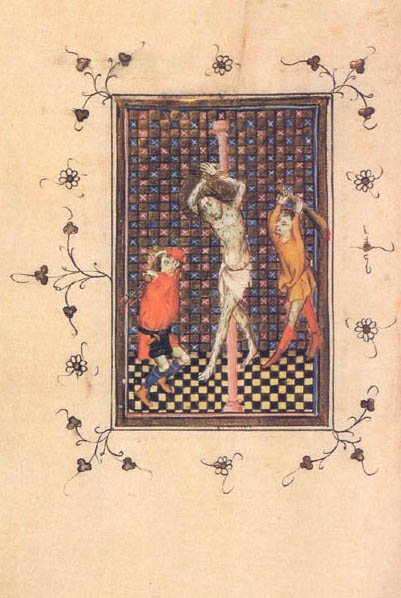

The Hours of the Cross and the Hours of the Holy Spirit are shorter prayers that often appear in Books of Hours, Pictures of the Crucifixion (or sometimes a cycle of the Passion of Christ—his sufferings between the night of the Last Supper and his death; see photo of “Flagellation of Christ”) and the Pentecost, when the Holy Spirit descended upon the Apostles, accompany these auxiliary prayers.

The “Obsecro te” (I beseech you) and “O intemerata” (O immaculate Virgin) are prayers addressed to the Virgin Mary and seek her aid as a divine intercessor to God on behalf of a repentant sinner. The majority of illuminations for these two prayers feature a Madonna, while others show the Pietà—a representation of Mary mourning over the dead body of Christ.

The seven Penitential Psalms usually have only one miniature that marks the beginning of the text: a picture of King David, the traditional author of the psalms, kneeling in prayer. Some Horae show the origin of David’s need for penance: Bathsheba, with whom he committed adultery, or David with Uriah, Bathsheba’s husband, whom David sent into battle to be killed so that David could possess his wife.

The Office of the Dead—prayers recited by both the clergy and lay people as part of the medieval funeral service—generally contains one miniature: usually a group of monks gathered around a coffin, chanting the text of the Office of the Dead. Alternatively, some of the most interesting and grisly illuminations show death personified as the Grim Reaper or as an animate, partially decomposed corpse come to claim one of the living.

Books of Hours speak volumes to the religious historian. The evolution of medieval piety, whose effects are still with us today, can be traced on the pages of Books of Hours: from the austere and pious early Horae with illuminations restricted to large inital letters framed by foliage, which were intended to praise God and the Virgin, to later Horae commissioned by the nobility and royalty that contained scores of elaborate miniatures painted by the greatest artists of the era and that seemed to be created to praise the individual owners of the Books of Hours.

Late medieval piety, in other words, incorporated a substantial element of public display. Aristocratic patrons, for example, often had portraits of themselves painted into the illuminations in their Books of Hours. They even had themselves painted in as principals in religious scenes. For instance, some 15th-century gentry are portrayed in their Books of Hours as present during the Nativity or the Adoration of the Magi, peering down devotedly at the Christ Child.

Perhaps the most outstanding example of this trend toward personal aggrandizement—and the most outstanding example of the illuminator’s art, as well—is the famous Savoy Hours, now housed at Yale University. Commissioned by Blanche of Burgundy, granddaughter of St. Louis, in the second quarter of the 14th century, the Savoy Hours originally contained 167 elaborately executed miniatures, many containing portraits of Blanche herself. By 1370, the Savoy Hours had passed into the hands of King Charles V of France. Charles, not content with a mere 167 illuminations, commissioned an extra 68 miniatures, most incorporating portraits of himself. Ultimately, the Savoy Hours passed into the hands of Charles’s brother Jean, Duke of Berry, who had long coveted it.

So taken was Jean with the Savoy Hours, he commissioned a “look-alike” Book of Hours that survives today as the Petites Heures du Duc de Berry. An avid book collector, Jean bought, commissioned and received as gifts manuscripts of the highest quality of the day. His masterpiece, a Book of Hours, he commissioned about 1413 called the Très Riches Heures, consists of 206 richly illuminated pages. One subject from this Book of Hours, the Garden of Eden, appears on the

How do we know so much about Books of Hours? The answer is simply that many have survived from the Middle Ages. Their popularity assured their survival. In fact, so popular were Horae that the most common place Books of Hours were virtually mass produced in the late Middle Ages from standard exemplars, both in manuscript and printed form. Yet even at this level, Books of Hours were luxuriously illustrated and treated as family heirlooms, to be passed on from generation to generation, much like family Bibles are today.

Throughout their long history, Books of hours were mainly produced in France. The second largest producer was what is now modern Belgium, the third, the Netherlands. Sadly, few English Books of Hours survive the Reformation of the 16th century. Most Horae were in Latin though some were written in vernacular languages, especially French and Flemish.

Little is known about most of the artists whose work features so prominently in Books of Hours. They are anonymous, known to scholars only by convenient sobriquets such as the Master of the Geneva Latini or the Master of the Harvard Hannibal. Only very late in the history of Books of Hours does the work of individual artists become identifiable by repetition of style and technique. The works of Jean Colombe, Jean Bourdichon and Jean Poyet are distinctive and distinguishable.

Books of Hours continue to yield new insights on the nature of medieval religious thought and art. Several great collections attract scholars from around the world, notably the Pierpont Morgan Library in New York City, the Bibliothèque Nationale in Paris, the J. Paul Getty Museum in Malibu, California, and The Walters Art Gallery in Baltimore, Maryland.

It has long been a truism that the Bible is the most-published book in the history of Western culture. But for almost 250 years, from about 1275 to 1525, Books of Hours (illuminated prayer books whose heart is a series of prayers devoted to the Virgin Mary) were the medieval best sellers. During this period the Book of Hours was the book most frequently commissioned by both the aristocracy and the middle classes. On the pages of Books of Hours the best artists created the most beautiful pictures, and the prayers on these pages offered the reader an intimate […]

You have already read your free article for this month. Please join the BAS Library or become an All Access member of BAS to gain full access to this article and so much more.

Already a library member? Log in here.

Institution user? Log in with your IP address or Username