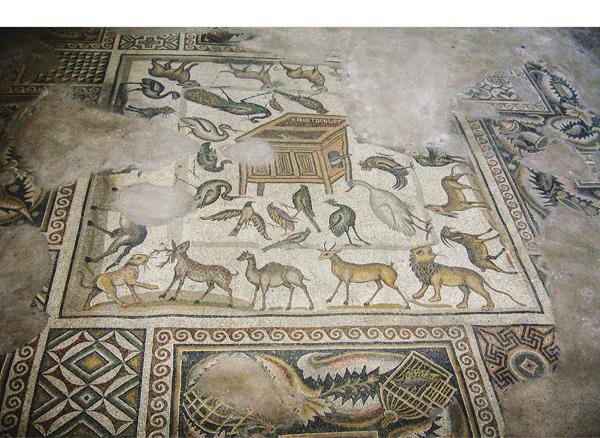

The recent discovery of a mosaic flood scene (Genesis 6:9-22; Genesis 7:1-18) in the fifth-century A.D. Huqoq synagogue in Israel highlights the unusual manner in which artists represented Noah’s ark during the early first millennium A.D.a The Huqoq scene, while fragmentary, is similar to a better-preserved scene from Mopsuestia, Turkey, found in a structure identified as either a church or a synagogue. Surprisingly, in both scenes the artists depicted Noah’s ark as a box on four legs. For someone like myself, who studies the iconography of ancient watercraft, this case is really one for the books! 1

The earliest representations of Noah’s ark—indeed the earliest-known depictions of any biblical scene—appear on a series of coins from the ancient site of Apamea Kibotos, modern Dinar, in western Turkey.2 The series spans the reigns of the Roman emperors Septimius Severus (A.D. 193–211) and Trebonianus Gallus (A.D. 251–253). On the coins’ reverse side, Noah and his wife stand inside the ark, again depicted as a box, complete with the identifier “Noah” (Greek: ΝΩΕ). Above the ark’s open lid appears a dove, bearing an olive branch, and a raven (Genesis 8:6-12).3 To the left of the ark, the couple stands with their right arms raised.

The Apameans perhaps found this scene attractive because their city’s epithet, kibotos (Greek: κɩβωτός), means “box.” Alternately, one tradition places Mt. Ararat, where Noah’s ark grounded after the flood, in the region of Apamea (Sibylline Oracles 1.240–324). This, too, might explain the curious appearance of a biblical motif on a pagan city’s coinage.

Apamea had a large Jewish population, and relations between the Jews and their Greek neighbors must have been good, as the Jewish historian Josephus counts it as one of the few Greek cities that neither attacked nor imprisoned its Jews at the outbreak of the Jewish War in A.D. 66 (War 2.479). In the late fourth century A.D., the Council of Laodicea, whose decisions speak to the circumstances in Phrygia generally, and in Apamea specifically, established restraints against the influence of Jews, which suggests that such fraternization remained a concern for the emerging Church.

The early Church Fathers, who considered Noah as representative of the Church or of Jesus, interpreted the story of Noah’s ark as one of redemption and salvation. Thus, the flood became a common theme in early Christian art. In one of the earliest Christian representations, on a sarcophagus dating to the early fourth century A.D., Noah appears alone standing in an ark, in the shape of a box, floating on water. Dating to the sixth or seventh century A.D., the Ashburnham Pentateuch depicts Noah’s ark as a box on legs. In the same way, other early Christian representations of Noah’s ark, such as within the late-second- to fourth-century A.D. Catacomb of Priscilla in Rome, depict it as a roughly cube-shaped box, sometimes on legs, typically with the cover open.

Irrespective of your view on whether Noah’s ark ever existed, I suspect that we all can agree that it would not have been a box on legs! The Hebrew Bible certainly makes no mention of legs on Noah’s ark. And yet in the early first millennium A.D., there can be no doubt that Jews, Christians, and even pagans conceived of Noah’s ark as a box with legs.

How are we to make sense of this oddity?

The Apamean coins may derive from an earlier Hellenic artistic tradition that depicted mythological pairs of characters, such as Auge and Telephus or Danaë and Perseus, on the sea in boxes.4 While this explanation is possible, these myths have nothing to do with a flood story. Rather, they both describe the attempted drowning of a mother and son by sending them out in a box to perish at sea.

Alternately, the ark may have served as an allegory for a sarcophagus bringing salvation to the dead in Christian funerary art. Nevertheless, the actual shape of the ark as it is portrayed is that of a box and not that of a sarcophagus.

A Greek inscription on the open cover of the box in the Mopsuestia scene may supply a clue to this enigma. It reads, “ΚΙΒΩΤΟΣ ΝΩΕ Ρ,” which could be rendered as either “the ark of Noah the R[edeemer]” or “the r[edeeming] ark of Noah.”5

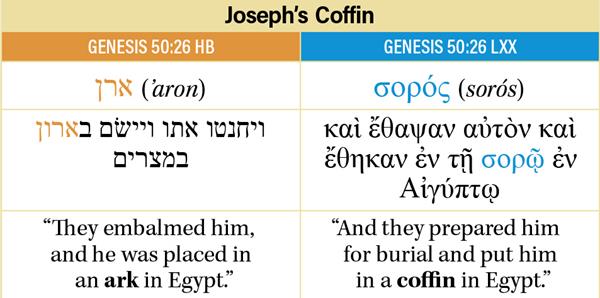

The Hebrew Bible uses the same term, tievah (Hebrew: תיבה), for both Noah’s ark and for the container in which the baby Moses was set adrift on the Nile River (Exodus 2:3, Exodus 2:5-6). This term itself perhaps derives from ṭubbû, a Babylonian type of watercraft. The Bible, however, employs an entirely different Hebrew term—aron (Hebrew: ארון)—for the “Ark” of the Covenant,b the same Hebrew term used for Joseph’s coffin (Genesis 50:26).

An interesting change in terminology takes place in the Septuagint, the Greek translation of the Hebrew Bible from the third century B.C., which employs the same term, kibotos (Greek:κɩβωτός)—meaning an enclosed wooden container used to store valuable objects—for both Noah’s ark and the Ark of the Covenant, while the Septuagint terms baby Moses’s floating receptacle a thibis (Greek: θῖβɩς) or “basket.” The reason for this change of wording in the Septuagint is unclear.

In rabbinic literature, the two terms—tievah and aron—appear virtually synonymously. The Mishnah, codified by Rabbi Judah ha-Nasi (the Prince) around A.D. 200, uses tievah to denote something of religious significance that is clearly not a watercraft (Ta’anit 2:1; Megillah 3:1). Perhaps it refers to a movable structure for storing Torah scrolls in a synagogue. The Jerusalem Talmud, which was compiled in the late fourth century A.D., describes the Ark of the Covenant (aron) as consisting of three tievahs, that is “boxes,” nestled one inside the other (Shekalim 6.1).c

It seems, thus, that the odd manner that artists represented Noah’s ark as a box, sometimes on legs, in its earliest appearances may have resulted from an overly literal interpretation of the Septuagint’s change in terminology: This would have caused the misunderstanding that Noah’s ark and the Ark of the Covenant were similar in shape. This imagery also eloquently expresses the remarkable influence the Septuagint had for its readers’ understanding of the Bible in antiquity.

MLA Citation

Footnotes

1. Jodi Magness et al., “Inside the Huqoq Synagogue,” BAR, May/June 2019; Karen Britt and Ra‘anan Boustan, “Artistic Influences in Synagogue Mosaics: Putting the Huqoq Synagogue in Context,” BAR, May/June 2019.

2. See David Falk’s article about the Ark of the Covenant’s imagery on Bible History Daily (www.biblicalarchaeology.org/ark).

3. I thank biblical scholar William Schniedewind for bringing to my attention the similarity in shape and manner in which Noah’s ark appears in some of these representations to items depicted in ancient synagogues, and particularly the table, with four legs, found in a structure identified by its excavators as a synagogue, at Magdala. See Marcela Zapata-Meza and Rosaura Sanz-Rincón, “Excavating Mary Magdalene’s Hometown,” BAR, May/June 2017.

Endnotes

1. See Shelley Wachsmann, “On the Interpretation of Watercraft in Ancient Art,” Arts 8.165 (2019), pp. 1–67. (doi:10.3390/arts8040165). Accessible free online at www.mdpi.com/2076-0752/8/4/165.

2.

Jeffrey Spier, “The Earliest Christian Art: From Personal Salvation to Imperial Power,” in Jeffrey Spier, ed., Picturing the Bible: The Earliest Christian Art (New Haven, CT: Yale Univ. Press, 2007), p. 1.

3.

While not obvious in the image in this article, better preserved coins from this series show the bird with a raven’s beak. See Spier, Picturing the Bible, p. 171, fig. 1: B.