The Dead Sea Scrolls: How They Changed My Life

038

In this issue four prominent scholars tell BAR readers how the scrolls changed their lives. Harvard’s Frank Cross is the doyen of Dead Sea Scroll scholars; his views come in an interview with BAR editor Hershel Shanks. In the pages that follow, Emanuel Tov, the publication team’s current editor-in-chief, who replaced the controversial John Strugnell, describes his personal challenges in this demanding assignment; Sidnie White Crawford, now a leading scroll scholar in her own right, was just a kid back then but with a view from the inside; and Martin Abegg, who was also just a young graduate student back then, tells us how he used a computer to reconstruct some of the secret unpublished scrolls to help him with his doctoral dissertation.

In subsequent issues we will continue this series with Oxford don Geza Vermes and New York University’s Lawrence Schiffman in July/August, and James Charlesworth of Princeton Theological Seminary and James VanderKam of Notre Dame University in September/October. Stay tuned.

039

Reminiscences of Scholarship, Anti-Semitism, Alcohol and Creating Texts

HERSHEL SHANKS: Where were you when you first heard of the Dead Sea Scrolls?

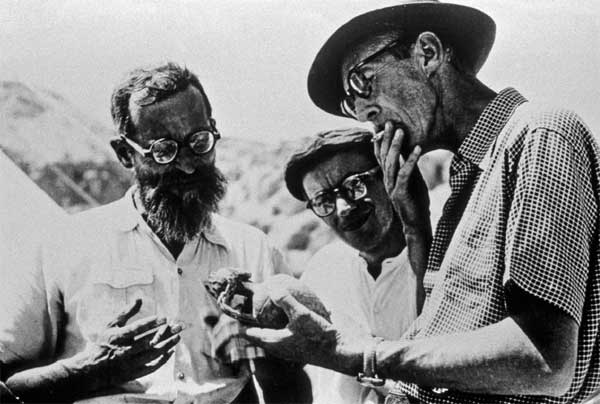

FRANK MOORE CROSS I was at Johns Hopkins doing my Ph.D. [David] Noel Freedman and I were sitting in the library. [William Foxwell] Albright came in with the first pictures that had come to this country of the Isaiah Scroll. Noel and I stayed up all night working through the text of those fragments in the photographs. We were absolutely overwhelmed. The more we studied the stuff in the brief time we had it, the more excited we became.

HS: How did you get the appointment on the scroll-publication team?

FMC: The American Schools [of Oriental Research] was asked to nominate someone. Carl Kraeling was president. I’m sure he conferred with Albright. I don’t know the details. All I know is that I got an invitation to go join the team.

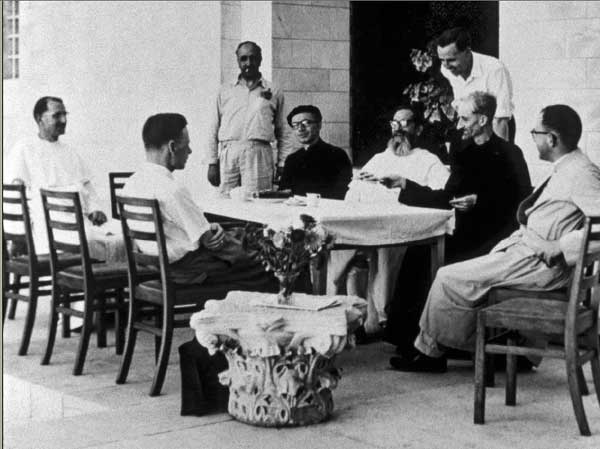

[Father Roland] de Vaux [the first editor-in-chief in Jerusalem] and [G.] Lankester Harding [director of the antiquities department in Jordan] worked out a plan to take someone from the American School and from the British School. And, of course, there was the French School. One from each and then they added additional ones. [Father Patrick] Skehan was added from the United States. Later, in some cases much later, others were added, including someone from the German School in Jerusalem.

HS: Many of the people on the team were quite young.

FMC: The youngest was John Strugnell. Just barely out of Oxford, he had a first [honors] in Greek and a second in Hebrew.

HS: How about another young man, John Marco Allegro?

FMC: That was a mistake of G.R. Driver’s [who recommended him].

040

HS: You don’t think well of him.

FMC: No, I don’t. Neither as a scholar nor as a human being.

HS: When did you go to Jerusalem?

FMC: I went out in June 1953, several years after I got my Ph.D. and published my first book (on Hebrew epigraphy). At that time all of the fragments excavated from Cave 4 [by de Vaux and Harding, as opposed to the more-than-500 different manuscripts looted from Cave 4 by the Bedouin] were in the [Palestine Archaeological] Museum and available to us. I was told to clean them. So I worked all summer on the excavated materials, something over 100 manuscripts.

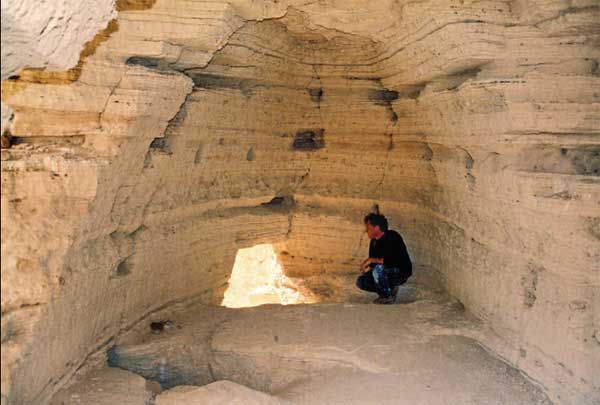

The first trip I took to Qumran was with de Vaux when he was about to begin excavation. I have a picture of [my wife] Betty Anne on that razor edge going into Cave 4 before they cut steps, and she’s screaming. [Józef] Milik and I were both on the dig for a while. We [on the publication team] wearied of cleaning manuscripts so we came down and worked for de Vaux for a while. Mostly we cleaned pottery [sherds] and tried to piece the pottery together.

HS: It was easy to go and see Cave 4 in those days.

FMC: You remember at least one person lost his life getting into Cave 4, going down that razor edge. That is when they finally banned that way of going down.

HS: I have been to Cave 4 a couple of times. One time—would you believe this?—I climbed up to Cave 4 from the wadi.

FMC: From the wadi bed? I’m very impressed!

HS: It wasn’t dangerous. The marl is so friable that I could get a grip in it with my foot.

FMC: I would not have dreamed of trying that.

HS: Tell me what life was like in the scrollery [at the museum].

FMC: Once the summer was over and I’d finished with the excavated material, all of the [Cave 4] material from the clandestine Bedouin digs came in. There was a series of these purchases. A great mass was bought out in the fall of 1953. We had bell-jar humidifiers and camel’s-hair cleaning brushes. We had plates of glass, one on top of the other, and as we tentatively identified a document by its script and leather, and sometimes by its content, we added fragment after fragment to a plate. In some cases manuscript fragments took up several plates. All of us were looking at everything and identifying them. We learned the scribes’ handwritings fairly quickly. One scholar, not adept at palaeography, indeed without an eye for form, thought he could identify a scribe by how he penned his lameds. Alas, the lamed evolved very slowly in this period, and he could not have selected a worse test.Identification of a scribe could be made first by the rough date of his script, and later by the peculiarities of his individual hand.I have remarked that we got to know individual scribes’ hands better than we knew our wives’ scripts.

HS: I think you’re the only person who can speak about life with the original Dead Sea Scroll publication team. John Strugnell is living, but in very poor health.

FMC: The others are dead.

HS: What about [Claus-Hunno] Hunzinger? He’s still living.

FMC: Yes, but he was there only for a very short time.

It was a happy scrollery. We were all using our given names. But Starcky was always known now as Monsieur Starcky.

HS: Did [Józef] Milik have a nickname?

FMC: For some reason we used to call him Milch.

HS: How did that come about?

FMC: I don’t know. Weary students making jokes, I guess.

041

HS: Was Milik a pleasant guy?

FMC: Very shy. He had a lovely giggle when something was funny. Unfortunately he was extremely sensitive to alcohol, and there were problems about that. I think one of the reasons for his alcoholism really was not being married. When we sat with him in our rooms at the American School, we’d have a glass of sherry and that would make him drunk. Later he became totally sober. He left the priesthood, married and moved to Paris.

One peculiarity of his was that he would not answer letters. Rarely he would write to you out of the blue or send a reprint of an article he had written.But to get answers from Milik you had to write to Starcky, who would give the letter to Milik, and then Starcky would reply what Milik had to say.

HS: Emanuel Tov, when he became editor-in-chief [in 1990], had the not-exactly-pleasant task of making some arrangement with Milik, who had this enormous assignment of material to publish. He wrote to Milik several times, and Milik didn’t reply

FMC: Tov should have written to Starcky. Starcky really played amanuensis to Milik. Milik was also very, very angry at having stuff taken away from him. These were [previously] unknown documents he was working on. He’d figured out what they were after years of work, when suddenly, pssh, gone. He didn’t like that. And he was a bit cranky.

Milik’s alcoholism was utterly different from [John] Strugnell’s. Strugnell just drank steadily. He had beer delivered by the case to the door of the dormitory at the École Biblique. He drank up a case and put out empties, and the case was refilled. He drank steadily most days. How his liver stood it, I don’t know. He perhaps had bipolar disease.

HS: Strugnell gave an interview to an Israeli journalist in which he exhibited very considerable anti-Semitism, to say nothing of his anti-Zionism. I printed that in English in BAR.a I then received a letter signed by 70 former Strugnell students and colleagues, yourself included, talking about Strugnell’s generosity and his brilliance and the support that he gave to these scholars, especially to younger scholars. This letter also seemed to ask forgiveness for, or understanding of, his anti-Semitism because of his mental condition and his obvious alcohol problem. Of course, I printed the letter.b

When Mel Gibson was recently arrested for drunk driving by an officer with a Jewish name, he went into a tirade of anti-Semitism, but nobody suggested that, well, this wasn’t really anti-Semitism because the poor man was drunk. Yet this seemed to be accepted with Strugnell—at least in this letter that you signed. Why did this anti-Semitism surface from John Strugnell if it wasn’t there somewhere in his psyche?

FMC: Strugnell clung to the theological view widespread among the early Church Fathers that Christianity superseded Judaism and that the covenant with Abraham ceased to be valid. He repudiates Paul’s notion that the covenant with Israel is eternal. So there’s a theological background to his anti-Semitism. Yet he had very friendly relationships with a number of Jewish scholars. I’m sure some of the signers of this letter were Israelis.

HS: It certainly included Jews. In my answer to this letter I said, “For the man, compassion; for his views, contempt.”c Several scholars who signed the letter were quoted in other media, and one of them said that when Strugnell would make derogatory remarks about Judaism, the person would call Strugnell on it and Strugnell would laugh and back down. Another signatory of the letter said Strugnell had long been known for his “slurs.” Still another affirmed that Strugnell believed in Christian supersessionism. The slurs and the jokes indicate that this was a kind of leitmotif. Would you confirm that?

FMC: He never confronted me with much of it. It was a mistake to appoint him head of the publication team. It should never have happened. 042The one good thing he did as editor is to bring more people in [to the team], including a number of Israelis.

HS: John had all of these years at Harvard before he gave his terrible interview. Did this anti-Semitism play out in any way at Harvard?

FMC: Not that I know of. We saw more of each other in Jerusalem than we did at Harvard. He was in the Divinity School, and I was in Arts and Sciences.

HS: In other words, you were as surprised as anyone else with this interview.

FMC: Yes. And angry. I was partly responsible for his coming to Harvard as a result of my association with him in Jerusalem. He controlled Greek and Hebrew from that period [the Second Temple period] to the extent of no one I knew. He was extraordinary. He read everything. But he could not give a general lecture. He ended up giving just seminars, in which he’d cover a very small unit, but thoroughly. He was not a good teacher at Harvard, but he was excellent with [doctoral] dissertations.

HS: His life as it’s played out is a real tragedy.

FMC: Yes. I don’t know to what degree this was a result of alcoholism.

HS: I was responsible for some of the difficulties of his later life [by publishing the interview in English], and after he was removed as editor-in-chief, despite what you might think was his justifiable dislike of me, we would regularly have a meal together in Cambridge when I came up. He was what I called a Christian gentleman.

FMC: I remember, too, Hershel, when this lawsuit was going on in Israel, he gave a perfectly balanced account of it.

HS: Yes. That is true. I think he was clearly sympathetic to the plaintiff, Elisha Qimron, but John also knew that Qimron contributed very little to the reconstruction of MMT. [Qimron successfully sued BAR for publishing a reconstruction of this document.]

FMC: Yes. It’s absolutely a scandal that Qimron’s name is put first [as author] on Volume 10 of DJD [Discoveries in the Judaean Desert, the series in which Qimron and Strugnell published MMT].

HS: Back in the 1950s you were a bunch of mostly young guys in Jerusalem called together to work on this material of extraordinary significance. But there were no Jews …

FMC: Couldn’t be, of course.

HS: Because the material was under Jordanian control. Was there any discussion about this? After all, they were Jewish documents. Everybody knew that they were Jewish documents, didn’t they?

FMC: No doubt. And all of us on the team were Hebraists, with the exception of Hunzinger.

HS: Was there any awareness of this?

FMC: Certainly. We were in continuing communication with Israel, with Moshe Goshen-Gottstein, during this whole period. We were aware that we were isolated. It was something that bothered your conscience. As you know, I was a very determined Zionist. My sympathies were overwhelmingly with Israel, probably the most of anyone on the team.

HS: As you sit here today, how do you look on the fact that these young guys were given assignments in perpetuity, as it were [to publish the scrolls], to the exclusion of many senior scholars, who bitterly complained.

FMC: As you know, my Biblical material was always available to anyone who had a scholarly reason for seeing it. I do have sympathy with the scholars [on the team] who put together these [previously] unknown documents and who took years to get this done; I thought they had the right to publish it.

HS: Suppose this arises again. Suppose there’s an enormous manuscript discovery. Should the publication assignments and rights be handled the same or differently?

FMC: I think there should be some kind of carefully planned-out 043arrangement. You want to have it so that good scholars will do the work, not drudges.

HS: The documents must be published pretty promptly?

FMC: Quite.

HS: What happens in a case like Milik’s? You have great respect for him. He worked for years putting these fragments together and making some sense of them, but he never completed his task. George Nickelsburg [a specialist in the book of Enoch] had to wait 30 years to see Milik’s fragments of Enoch.d From Nickelsburg’s point of view, Milik hoarded and kept them secret.

FMC: That was wrong. Enoch is a [previously] known book.

HS: Would it have been different if it had been [a previously] unknown book?

FMC: I think so.

HS: You mean, wait 30 years to show it to the public?

FMC: Well, it should be done faster than that, but I have enormous sympathy with Milik on this score. Papyri from Egypt go years and years and years and years—over a century [without being published]—the Oxyrhynchus Papyri.

HS: But that doesn’t justify it, does it?

FMC: The Cairo Geniza material is still unpublished. [Most of it was brought to England in 1897.]

HS: But you can go to Cambridge [University] and see it. Anybody can see it. They are now digitizing it.

FMC: But I told you my stuff was available. It’s a tough question because you’re talking about someone’s life. Milik was at it for 30 years, and he worked hard. And then you have someone else publish the document. In effect, you’ve stolen those years from Milik.

HS: Isn’t it adequate to give him credit for the work he’s done?

FMC: No. Not if you just say in a footnote, “Thanks to Milik, we have this document.”

HS: What about giving him co-authorship?

FMC: That’s a different matter. That might very well be the solution.

HS: Can you tell me b’regel echad [on one foote] what you think the effect of the scrolls has been on the public, not on scholars?

FMC: I think it’s the awareness of what can most easily be labeled as “apocalyptic Judaism.” This is new. We had some hints of it, but the degree to which there is a thriving bunch of apocalypticists and their followers at precisely the time when Christianity and Rabbinic Judaism crystalize, I think is of great interest.

HS: But if I were to take a reasonably educated Jew or Christian and say, “Sir or Madam, did you know there was an apocalyptic Judaism at the turn of the era?” they’d say, “Well I’m not sure what that is, but so what?”

FMC: [Laughs.] It indicates the close kinship of early Christianity and the rich Judaism of that period. Those who say that Rabbinic Judaism had no apocalyptic elements are repudiated.

HS: What do you mean by apocalyptic?

FMC: The end is near. And when the end comes, the victory of God and his armies will overcome the forces of evil. The apocalyptic texts from Qumran interpreted the sacred texts as applying to their own time.

The Daniel material [in the Hebrew Bible] is apocalyptic, probably the best example.

HS: But we’ve always had that, haven’t we?

FMC: We have it, yes.

HS: So why do you say that it’s new?

FMC: Because we have more Daniel material and Enoch material and much more apocalyptic material. Enoch has been considered by many scholars to be Christian. Now it’s clear: It’s Jewish, except for some glosses that are apparently from Christian hands—interpolations.

I don’t know what the public sees. I’m too much involved in this to be able to see it. The [recently discovered] Gospel of Judas [from the third–fourth century] has had a strong attraction to the public. The documents from Qumran, however, are far more important.

HS: But they don’t have a marketing machine like National Geographic has.f

FMC: That’s right. I think there’s been a revolution in our knowledge of the history of this period [the turn of the era, the period covered by the Dead Sea Scrolls]. I think there’s been a revolution in our knowledge of the development of the Hebrew Bible. These are stunning things that we still have not completely assimilated—the scholars, much less laymen. It will be at least two more generations before this stuff is really assimilated. There’s so much richness, and there’s so much drag of scholarly positions on seeing the new and seeing the synthesis of what we have now.

044

Taking the Helm; Media Pressure Delays Publication

According to one press report, I actually discovered the Dead Sea Scrolls! Shortly after I was appointed editor-in-chief of the Dead Sea Scroll publication team in 1990, I was interviewed by U.S. News and World Report, which accurately reported that when the scrolls were discovered, I was six years old. This was then picked up by a newspaper for the Korean Christian community in the United States, whose headline read: “When Emanuel Tov was six years old, he discovered the Dead Sea Scrolls.”

Although this was a slight exaggeration, I was, in fact, interested in the scrolls at an early age. When I was 13, growing up in Amsterdam, I bought a little booklet about the scrolls in Dutch written by the great scholar Adam van der Woude, with whom I would work nearly 50 years later. At 14, while in England on my first trip abroad, I bought a Penguin book on the scrolls by John Allegro, using what little money I had to buy books instead of food. The result of that strange priority was that I fell ill.

After immigrating to Israel in 1961, I consulted the scrolls that had been published at that time in connection with my Biblical studies at The Hebrew University. There I was greatly influenced in my study of the scrolls by a series of great teachers—Shemaryahu Talmon, Moshe Goshen-Gottstein, Isaac Leo Seeligmann, David Flusser and Yehezkel Kutscher. I focused on the history of the text of the Hebrew Scriptures, especially the Septuagint (LXX), a Greek translation of the Hebrew scriptures made for the Jews of Alexandria, Egypt, beginning in the third century B.C.E.

Not until my two years at Harvard in 1967–1969, however, did my studies begin to focus on the scrolls. At Harvard I had the privilege of reading several unpublished fragments of the Book of Samuel in a private tutorial with Frank Moore Cross, who had published part of his scroll assignment 14 years earlier and was to complete the job in 2005 under my supervision.1 The reading of the Samuel a and b scrolls from Cave 4 (4QSama,b) under Frank’s guidance opened up a new world to me. I also received first-hand experience in deciphering scroll photographs of non-Biblical scroll fragments from one of the most insightful scholars in this field, John Strugnell, who was later to be appointed and then removed as editor-in-chief of the scroll team. Studying with Professors Cross and Strugnell paved the way for my later work on the scrolls. My fellow students and I realized that we were the first, or almost the first, to tackle the thorny problems of these fragments. We learned a lot, and we also helped our teachers to develop further their own ideas. It was all very exhilarating.

Back in Israel as a young teacher at The Hebrew University, I continued to develop my interest in the scrolls while pursuing my research on the Septuagint, on which I published most of my research until 1990. What the Qumran scrolls and the Septuagint have in common is that both give us insights into the text of the Bible in the last centuries before the turn of the era. It is especially intriguing when both the texts from Qumran and those from the Septuagint differ from other ancient 045Hebrew texts that developed into the traditional Jewish text of the Bible known since the early Middle Ages as the Masoretic Text, or MT for short. The Masoretic Text is the best-known text of the Hebrew Bible. The general public, along with many scholars, often think of MT as the only text of the Bible. It is the text printed in all editions of the Hebrew Bible, and it forms the base for all modern Bible translations. But the fact is that in ancient Israel, Biblical texts circulated in several different forms. We now describe some texts from Qumran as precursors of the medieval MT and others as the Hebrew base text of the Greek Septuagint. In short, scholars study the Septuagint and the Qumran Biblical scrolls to gather maximum information on the early text of the Bible. Scholars use these new insights not only when focusing on small details in the text, but also when analyzing some major issues. For example, modern scholarship on the book of Jeremiah is impossible without reference to the Septuagint and the Dead Sea Scroll texts of that book in Hebrew. In them, Jeremiah is much shorter than the traditional Masoretic Text and is arranged quite differently.

My interest in text criticism of the Hebrew Bible kept me in close contact with the scrolls, but that interest was soon to take a more tangible form. In 1985, at a party at the École Biblique et Archéologique Française in Jerusalem, the then-editor-in-chief of the publication team, Père Pierre Benoit, took me aside and asked me if I would like to edit (i.e., publish) the Greek Minor Prophets Scroll for the Discoveries in the Judaean Desert (DJD) series, the official publication series of the scrolls put out by Oxford University Press. The Greek Minor Prophets Scroll had been found not at Qumran but at Nahal Hever, a wadi near Quman, and dated to the middle of the first century B.C.E. I was highly honored by the offer, for I would be the first Israeli to publish in DJD. The burden of this responsibility was a pleasant one.

I asked Robert A. Kraft, a specialist in papyrological matters and my host during a 1985–1986 sabbatical at the University of Pennsylvania, to collaborate with me. From Bob I learned techniques for studying the text with a computer and reconstructing its original physical shape. The publication of the Greek Minor Prophets scroll had originally been assigned to Dominique Barthélemy, who kindly provided me with his personal notes on the scroll beyond his published studies.

I delivered the manuscript of the volume to Oxford University Press on rather primitive computer files, later changed to a more sophisticated computer format. Published in 1990 as DJD VIII, it appears to have been the first computer-assisted publication in our field. Later, we made vast and very sophisticated use of the computer in delivering actual printed pages to the publisher.

A pre-publication flier for the Greek Minor Prophets scroll, now in my collection of Qumran memorabilia, is the only evidence of a political faux pas in connection with DJD VIII that was avoided only at the last minute. During a short interlude between 1962 and 1968, DJD volumes III, IV and V were published as Discoveries in the Judaean Desert of Jordan. Otherwise, the series was, and is, known simply as Discoveries in the Judaean Desert. Since 1968, the words “of Jordan” have been omitted. By a curious mishap, however, these 046words almost returned in 1990—in my DJD volume. To my great surprise the pre-publication flier prepared by Oxford University Press announced that my volume (the first by an Israeli author) would be in the series Discoveries in the Judaean Desert of Jordan. The gaffe was quickly corrected and the flier withdrawn. I may have the only original copy of the flier still existing.

After publication of DJD VIII, I continued to work on several Qumran scrolls from the famous Qumran Cave 4. I would have continued my quiet life as a Biblical scholar and Qumran specialist had I not been asked in the summer of 1990 to replace John Strugnell as editor-in-chief. That was a turbulent year for the scrolls. Pressure had been mounting on the Israel Antiquities Authority (IAA) to advance the stalled publication of the scrolls, and the IAA was in bitter conflict with Strugnell, my former teacher and the editor of my DJD VIII. A brilliant scholar, John also had major problems. At the height of the tension, John was fired, and I was asked to replace him. The IAA, under the leadership of Amir Drori, wanted an Israeli with experience editing the scrolls to reorganize the editorial team and bring to speedy completion publication of the scrolls. At first I resisted, but after long discussions and much pressure, I agreed. My main condition was that the IAA would ask The Hebrew University to release me from half of my duties. This indeed happened for a period of eleven years, and even during the IAA’s most difficult financial years, they paid half of my university salary.

I sometimes regretted that moment of weakness in 1990 when I agreed to accept the assignment. I doubt whether I ever would have agreed had I realized the enormity of the enterprise, the struggles I would have with several institutions, and the daily pressures involved in convincing scholarly colleagues to complete their work on the texts.

In some ways, I started off on the wrong foot. I could not begin work immediately because I had already made my plans for 1990–1991. I was about to leave for a sabbatical doing research in the Netherlands. Then when I was about to tackle the lagging publication process in the fall of 1991, a major storm broke out in our little world: Pictures of the unpublished scrolls were released by the Huntington Library in Pasadena, California, where security copies had been deposited. The only practical result of this political and media storm was that the work of publication was delayed by 6 to 12 months since we needed to spend so much energy on self-defense.

The good news is that from the fall of 1991 onwards, I could work toward the goal that I had set myself and for which I had been appointed: the reorganization and enlargement of the international team and the speedy publication of the scrolls.

Although the fragments had been cleaned, sorted, photographed, as well as identified and partially inventoried, in the 1950s, much remained to be done. When a group of fragments that was once considered to represent a single Qumran composition was later identified as representing two separate compositions, a new Qumran scroll was born, so to speak. In this way, the number of Qumran scrolls has grown from 600 to 930.

We also gave names to the compositions. Once included in the official edition, however, a name cannot be changed. Some of these names are utterly subjective. We are still haunted by the so-called Wiles of the Wicked Woman (4Q184), so named by John Allegro. Even the famous Temple Scroll is a misnomer, according to many scholars, because the Temple is not the central topic in all sections of this longest of the Dead Sea Scrolls.

The reorganization of the publication team and reassignment of the texts from scholars who had failed to publish their assignments created some delicate problems. Texts had to be taken from scholars to whom so many items had been assigned that, in order to complete their work, their life spans would have to compete with Methuselah. It was a very unpleasant task and resulted, for example, in Józef Milik, one of the most brilliant of the editors, ceasing to cooperate with us, because he was opposed to working on a limited number of texts.

With the involvement of the Israel Antiquities Authority, the publication enterprise was reorganized and the number of scholars on the team was enlarged. In the end, 53 additional scholars were added to the team, bringing the total number of editors who had worked on the project to 98. The only criterion for choosing editors was proven competence. The percentage of Israeli scholars, who had been barred from this work during earlier decades, naturally increased, but we also added scholars from North America and Europe.

Dead Sea Scroll scholars, who deal with thousands of minute details, are bound to change their minds very often. I know. I am one of them. And every time we change our minds, we think our careers depend on it. It can be a problem.

Some scholars do indeed work very speedily. One editor, for example, finished 80 pages of text in a year (that’s very fast). Natural procrastinators, on the other hand, are the weak point in any publication project. Intuitively, I have tried to adapt myself to each person’s 047modus operandi by being sweeter to some, harsher to others and occasionally trying both approaches. I have also tried to convince my colleagues that there’s life after DJD (but I have not always succeeded). As well as making many new friends, I also created a few non-friends. But as a rule it was a pleasure working with the editors, among whom I count four Jims, three Johns, two Joes, four Mikes, two Sarahs, and even Peter, Paul and Mary. There was a sprinkling of Misters and Misses and a majority of Doctors or Professors or Professor Doctors, and in one case a Professor Doctor Doctor, representing 11 countries, several religions, all age groups and both sexes.

What has the publication project achieved? All the Qumran fragments have been made available in critical editions and photographic form, mainly in the official DJD series. In 1955, the British director of the Jordanian Department of Antiquities, G. Lankester Harding, envisaged that publication of the Dead Sea Scrolls could be accomplished in five volumes!2 In 1990, we thought in terms of 30 volumes. The current total is 37 large-sized volumes, comprising 11,984 pages and 1,339 plates.

It has not always been easy for scholars to focus on DJD with the world burning around us. Whether or not to leave a space between two words in the transcription of a text may seem irrelevant, but that decision has to be made. It is probably not a bad idea to be an ostrich from time to time.

Did the Dead Sea Scrolls change my life? Yes, very greatly! I learned much about many things: scrolls, people, fund-raising and setting up a large international project. Now I have also learned that there is life after DJD.

Sidnie White Crawford

Present at the Breakdown; Learning from the Greats

I am one of “the kids,” the younger generation of Dead Sea Scroll scholars privileged to work on the first editions of the manuscripts. Perhaps it was being in the right place at the right time. I was there—at Harvard University in the 1980s.

My interest in the scrolls actually began as an undergraduate at Trinity College in Hartford, Connecticut. I took a course in apocalyptic literature taught by Professor John Gettier. One of the texts we read was the so-called War Scroll, The War of the Sons of Light Against the Sons of Darkness. I remember it was in the earliest Penguin edition of Geza Vermes’s The Dead Sea Scrolls in English. What a thin volume that was, compared to today’s hefty tome! I found the text fascinating and resolved to learn more.

After completing a master’s degree in theology at Harvard Divinity School, I entered the doctoral program in the adjacent department of Near Eastern Languages and Civilizations. The faculty included two members of the original editorial team assigned to publish the Cave 4 fragments from Qumran: Frank Moore Cross and John Strugnell. My first 049encounter with Cross was as his advisee. With great trepidation I trekked from the Divinity School to the Harvard Semitic Museum at 6 Divinity Avenue to meet the great man in his office. He was extremely kind, as he always is to young scholars, and so began the most important relationship of my scholarly career.

My first encounter with the scrolls, however, came with John Strugnell. Strugnell taught Second Temple Judaism (then called Intertestamental Literature). To many readers, Strugnell’s name is infamous; he has been roundly condemned in both scholarly circles and in the popular press for certain extremely unfortunate actions taken and anti-Semitic remarks made toward the end of his career. All of that is regrettably true; Strugnell suffered from severe bi-polar disorder coupled with alcoholism, and the regrettable events in the early 1990s stemmed directly from those conditions. I was a witness to his mental breakdown. It was one of the saddest and most frightening things I have ever seen.

However, John Strugnell was a brilliant scholar, an accomplished linguist and a tireless mentor to his students. He spent endless hours working with me (and many others), training me carefully in the developing field of scroll scholarship. After Frank Cross, Strugnell was my most influential teacher, and I will always be grateful to him.

As I pursued my interest in the scrolls, the famous (or infamous) Harvard 200 seminar (the seminar for Bible Ph.D. candidates) loomed on the horizon. I decided to work on the Damascus Document, one of the rule books belonging to the community at Qumran. I wanted to try to understand the relation of the two manuscripts (designated A and B) of the Damascus Document by means of textual criticism. When I presented a preliminary paper on the subject to the seminar, my faculty critic, James Kugel, ripped it to shreds, leaving me a quivering puddle at the end of the table. As I was trying to formulate some kind of panicky response, Frank Cross stood up and said, “Well, I think it is a very fine paper!” He then proceeded to defend me, step by step. I was one very thankful doctoral student. That paper was later published, at Jim Kugel’s suggestion, in Revue de Qumran.

When it came time to choose my dissertation topic, I made an appointment with Cross to discuss the possibilities. He said, “I think, Miss White, that you have two choices. You can continue your work on the Damascus Document, or you can help me by editing some of the Deuteronomy manuscripts in my Scrolls lot.” Deep breath. “I think, Professor, that I would like to work on the manuscripts with you.” And so a Scroll editor was born.

Cross assigned me six manuscript fragments: 4QDeuta,c,d,f,g,n (Deuteronomy fragments from Qumran Cave 4). He gave me all the photographs of those manuscripts that had been taken in the 1950s, and he also wrote a letter of introduction for me to Eugene Ulrich, professor at Notre Dame, who was overseeing the publication of the Biblical manuscripts in the official series Discoveries in the Judaean Desert. I received a gracious welcoming letter from Ulrich, the start of a warm personal relationship with an important mentor.

My first task was to go to Jerusalem and learn to work with the original manuscripts themselves. My guide would be Strugnell, who by this time was spending half of each year in Jerusalem. I flew to Israel in late November 1986. Strugnell had suggested that I stay at the École Biblique, a short walk from the Rockefeller Museum where the Cave 4 fragments were (and are) housed. The École is a French Dominican convent built in the 19th century. At the time, it had no central heating. My overwhelming impression was cold! I wore my coat all the time. I remember one day Émile Puech, now a leading scroll scholar who at the time was the assistant librarian, found me shivering pitifully in the subterranean basement library. With true French gallantry, he found three portable heaters to set around me so I could work in relative comfort.

Each morning I would walk to the Rockefeller Museum, descend to the basement on a British Mandate-era freight elevator and proceed to the tiny room where the scroll fragments were kept in locked cabinets. I would transcribe each manuscript, fragment by fragment, noting every detail of the leather, measuring every column, line and margin, and comparing this with the photographs taken in the 1950s.

It was during these morning sessions that I met the fourth important figure in my scroll career, Emanuel Tov of The Hebrew University. Tov later became editor-in-chief of the entire scroll project, as well as my collaborator on the manuscripts known as 4QReworked Pentateuch.

In the afternoons I would work in the library, beginning the text-critical work central to any edition of a Biblical manuscript. About two hours before dinner, I would report to Strugnell’s study, where he would review, in sometimes painful detail, everything I had done that day. Thanks to him, I completed a transcription of all six Deuteronomy manuscripts on that first trip.

050

December 1986 also marked my first trip to the ruins of Qumran, led by Strugnell himself. We rented a car in Jerusalem, and with Leong Seow (now of Princeton Theological Seminary) and his wife, Lai King, we set out. I drove, a braver act than I realized at the time. Strugnell navigated, needing no map with his superb knowledge of the roads in the Judean Desert. We went first to Masada, then to Ein Gedi and the Dead Sea, and finally to Qumran. Strugnell led us around the site, peppering his remarks with reminiscences about the near-legendary scroll heroes: de Vaux, Milik, Starcky, Cross and the Bedouin excavators.

Finally he asked, “Is there anything else you would like to see?” “Yes,” I said, “I would like to go into one of the caves!” He looked at me with scorn. “My dear Sidnie, young ladies do not go into caves!” That was the end of my spelunking ambitions for that day.

On the trip back to Jerusalem, Strugnell asked us if we would like to drive on an old Roman road. “Sure!” we replied, having no idea what we were getting ourselves into. Suddenly I was driving up the switchbacks of the old Roman road in the Wadi Qelt, with dusk coming on fast. Without warning a truck appeared, coming down the road we were attempting to climb. I had no choice but to back down the one lane, with a sheer drop-off on the left, to a spot where the truck could safely ease by me. Several scholarly careers were in jeopardy that day.

After I finished my dissertation, Strugnell invited me to take his place in editing the four manuscripts that eventually became known as 4QReworked Pentateuch (4Q364-367). Strugnell had already asked Emanuel Tov to collaborate with him on this project, and Tov graciously accepted a very young, “wet-behind-the-ears” post-doc as his junior partner. I began work in earnest on these manuscripts in 1989 while I was a National Endowment for the Humanities fellow at the W.F. Albright Institute for Archaeological Research in Jerusalem, the beginning of a long and happy association with the Albright. [Sidnie White Crawford later became president of that institution.—Ed.] This was the period when dissatisfaction with the delay in publication of the scrolls moved out of scholarly circles and into the public eye, and I had my first brush with the popular media. I appeared on Good Morning America with Strugnell and Gene Ulrich, much to my mother’s delight. I also gave countless interviews to newspapers and magazines, learning to speak in “sound bites,” a skill that has served me well since.

Looking back on those days of editing manuscripts, it is striking to me how much we were changing our views even as the manuscript editions took shape. For me, the greatest change as a result of my work on the scrolls concerns the textual history of the Hebrew Bible and the formation of the Jewish canon. Before the discovery of the scrolls, it was understood that the text of the Hebrew Bible was not completely fixed until the 10th century of our era. Until then, variants in the text existed (mostly the result of scribal error). The task of the text critic was to weigh and choose between the variants. The goal was to determine the “original” text. The Dead Sea Scrolls have changed all that. Now we realize that the textual tradition of what became the Biblical books was far more fluid than we ever imagined. We can isolate different textual families (for example, the pre-Masoretic family of texts, the Septuagint family of texts and the pre-Samaritan family of texts of the Pentateuch). For some books, such as Jeremiah, we now recognize two editions of the same text.

The remarkable thing is that all these variant manuscripts were stored together in the caves at Qumran, indicating that in the late Second Temple period, devout Jews were not concerned at having a fixed, unchanging text of Scripture. Cross, Ulrich and Tov, my teachers and mentors, have been at the forefront of this research.

We have also realized that the very terms “Bible” and “Biblical” are anachronisms in the Second Temple period. In this period, there was no Bible as such—no list of canonical (authoritative) books. A core group of authoritative books was accepted by all Jews as Scripture: the Torah (Pentateuch), the Prophets and the Psalms (although the text of the Psalter was not fixed). Beyond this core, however, the edges begin to blur. At Qumran the books of Enoch and Jubilees had scriptural authority, but they did not make the final cut of the Hebrew Bible. On the other hand, at Qumran the books of Chronicles probably had not attained scriptural authority. The book of Esther, which was not found at Qumran, certainly did not have scriptural authority, since the Qumranites did not celebrate the festival of Purim, the Jewish festival that is still celebrated today by reading the Book of Esther in the synagogue. Thanks to the scrolls, we now realize that our familiar Jewish canon of 24 books did not exist until at least the late first century C.E.

Did the Dead Sea Scrolls change my life? Indeed, they did. I have been fortunate to work on these priceless ancient manuscripts and to work with some of the giants in the field. For that privilege I have to thank those unknown Qumranites who hid their precious treasures in the caves in 68 C.E., as the Roman Legions marched from Jericho toward Qumran.

051

“Rabbi Computer” Recreates Unpublished Texts

It began in fourth grade. I was living in upstate New York (where my father was studying for his Ph.D.). My class met in the school library due to a bit of overcrowding. It was there that I discovered the joy of reading. My desk was within an arm’s reach of books about Mickey Mantle, Babe Ruth, Lou Gehrig and other of my baseball heroes. But it was another book that first came to my notice that year and that continues to be the center of my attention to this day: the Hebrew Bible. It was read backwards and was full of mysterious characters. Each Wednesday a group of students from School 18 were allowed to leave classes mid-afternoon to learn to read this mysterious book. The rest of us—about half of the class—were escorted to the neighboring Methodist church, where we mindlessly colored (between the lines). I can still feel my disappointment.

My first real opportunity to do something about this keen frustration was when I enrolled at Northwest Baptist Seminary in Tacoma, Washington, in 1979. There I dug into Hebrew, Aramaic, Syriac and Ugaritic—subjects the learned professors were as eager to teach as I was to learn.

After graduation, I became a part-time pastor and a part-time teacher, but soon decided to pursue a graduate degree in Semitic languages. A good friend of my father’s, Sam Rothberg, pointed the way to The Hebrew University, and I moved my young family (a one-year-old daughter and a pregnant wife) to Jerusalem. In retrospect, this all seems a bit crazy, but as it turned out, it was one of the best decisions I ever made (even my wife agrees … now).

One of the classes I signed up for was a two-term seminar on the Septuagint of Jeremiah, led by Professor Emanuel Tov. But as the fall semester approached, I began to hear rumors that Professor Tov had decided to change the subject of the seminar to the Dead Sea Scrolls. Disappointed at the switch, I decided to drop the seminar and look for something else. I still hear ringing in my ears the advice of an older graduate student warning me not to get involved with the notorious Dead Sea Scrolls: “A dead end,” he told me. (Incidentally, he has also ended up devoting his scholarly life to Dead Sea Scroll research.) As luck would have it, I could find no other class to fit my schedule. I finally gave in and took Tov’s seminar. I was soon captivated by the adventure that is Dead Sea Scroll study.

After three years at The Hebrew University, I decided to finish my studies at Hebrew Union College–Jewish Institute of Religion in Cincinnati, Ohio. Although HUC-JIR is the academic and professional development center of Reform Judaism, the institution has had a longstanding interest in interfaith dialogue. Over the years, the graduate school has hosted numerous non-Jewish graduate students who have access to a brilliant 052faculty and one of the finest research libraries in the world. I fully intended to continue with my study of comparative Semitics, but I learned that Professor Ben Zion Wacholder (who had just published his controversial Dawn of Qumran) was looking for a research assistant. I applied and became one of a privileged string of graduate students who served as “eyes” for the nearly blind Professor Wacholder. It was not long before I once again turned my attention to the Dead Sea Scrolls. This time, however, the hook was set.

In the midst of writing my dissertation on the scroll known as The War of the Sons of Light Against the Sons of Darkness, Professor Wacholder began chasing down rumors that a concordance of unpublished Dead Sea Scroll manuscripts had been produced under a strict ban of secrecy. No shrinking violet, Ben Zion went right to the top, to the then-editor-in-chief John Strugnell. From him he learned that the rumors were true. A concordance, a kind of index of each word together with a few words of surrounding context, indeed existed. Strugnell had even promised a copy to Hebrew Union College. In short, a copy of this very private (intended only for the members of the scroll-publication team) and otherwise-secret concordance was made available to Professor Wacholder.

Upon seeing the nature of the concordance—key word in context rather than a simple word list—I decided to explore the possibilities of “unconcording” some of these closely held, unpublished documents that related to my research on the War Scroll. With the help of a computer, this proved eminently doable. Once I had reconstructed the texts that I needed for my dissertation, the next obvious question was: Why not continue reconstructing other unpublished texts by this method? So I began reconstructing manuscripts that I knew would prove useful to Professor Wacholder’s research.

Early in 1991 I brought him 50 pages of reconstructed text. After a few minutes of examination and discussion he announced the fateful words: “We must publish!” Which evoked my unvoiced reaction, “And I’ll never find work!” Eventually, however, after numerous conversations with friends, family, colleagues (several of whom shared fears of my eventual unemployment) and finally even Hershel Shanks at the Biblical Archaeology Society, I decided that Ben Zion’s reaction was an accurate assessment given the languishing rate of scrolls publications.

Initially we continued work on the reconstructions as I had begun, a cut-and-paste job in a word processor following the context manually and verifying the order with the numbers on the 3″x5″ cards that were occasionally visible in the concordance. But as the tedious and repetitive nature of this approach became apparent, I began to experiment with programming solutions to “teach” the computer to do the repetitive tasks. I eventually typed in the entire concordance and fed it through a Hypercard script that I had named “Glue” (not “Rabbi Computer,” as the press called it!). Then Professor Wacholder and I carefully edited the reconstructions making corrections and suggesting alternate readings. And publish we did, in September 1991.

Our fascicle of unpublished fragments published by the Biblical Archaeology Society proved to be the first of three key events regarding the Dead Sea Scrolls that fall. On the heels of our publication, the Biblical Archaeology Society also published an edition of photographic plates prepared by Robert Eisenman and James Robinson. (The source of these photographs has not been revealed to this day!) Then the Huntington Library in San Marino, California, revealed that it possessed a duplicate cache of photographs that had been deposited there for safekeeping against the possible loss of the originals in Jerusalem. The Huntington Library announced that it would make these available to all scholars.

In the months that followed, the scrolls were front-page news. Those of us who had dared take on the official “cartel” became the darlings of the popular press. As a result, the Israel Antiquities Authority was faced with a monumental decision. To its credit, rather than going on the offensive, it chose to lift the barriers to access. After more than 40 years of secrecy, the scrolls were finally available to all.

Our initial edition of reconstructions— we eventually published three fascicles, plus a concordance—has served two additional and important purposes. First, the publication of the scrolls moved into high gear under the able oversight of the new editor-in-chief, Emanuel Tov. Although we may never know just how large a part our reconstructions played in the increased speed of subsequent publication, the facts are suggestive. By the fall of 1991, only seven volumes of text editions had appeared in the official Oxford University Press series. In the 15 years that have followed, 29 additional volumes have appeared, with four more nearing completion. Second, the official editors now have ready access to the transcriptions of the first generation of scholars. A review of the notes in the official editions published since 1991 and the numerous references to “Wacholder and Abegg” attests to just how useful our publications have been to newer scroll scholars.

Thankfully, my initial fears of joining the unemployment line were unfounded. Indeed, it is hard to imagine that my career would have been so successful had I opposed Professor Wacholder’s 053determination to publish. After a three-year term at Grace Theological Seminary in Winona Lake, Indiana, I headed to Langley, British Columbia, to found—with my friend and colleague Peter Flint—the Dead Sea Scrolls Institute on the campus of Trinity Western University. We are now in the 12th year of our partnership, with, I trust, the best years yet to come.

Perhaps the sweetest irony was my official appointment to prepare a three-volume concordance to the official scroll publications. The one-time pirate has in essence been handed the keys to the treasure house.

One aspect of Dead Sea Scroll research sets it apart from the endeavors of my other religious studies colleagues: public interest. The Dead Sea Scroll exhibit currently making its rounds in the United States illustrates the breadth of this interest. It makes no difference whether the museum is in the “Bible Belt,” as is Discovery Place in Charlotte, North Carolina, or many philosophical miles away, as is the Pacific Science Center in Seattle, Washington: The Dead Sea Scrolls have struck a responsive chord with the public and set attendance records in every venue. The interest is as broad as the Bible, on the one hand, or The Da Vinci Code, on the other. Taking advantage of this keen interest—“on tour with the Dead Sea Scrolls,” as my colleague Peter Flint and I have come to call it—gives us a rare opportunity to “smuggle in” a whole host of important Biblical studies topics to engage the public’s interest.

A recent trip south across the U.S.-Canadian border to speak about the scrolls in Seattle brought the usual question from the young U.S. Customs officer: “Purpose of your visit?” My stock response: “To see the Dead Sea Scrolls in Seattle.” “Oh,” she said, “and what kind of band is that?” Indeed, I am a Dead Sea Scroll groupie. So be it. It’s a pretty good gig.

In this issue four prominent scholars tell BAR readers how the scrolls changed their lives. Harvard’s Frank Cross is the doyen of Dead Sea Scroll scholars; his views come in an interview with BAR editor Hershel Shanks. In the pages that follow, Emanuel Tov, the publication team’s current editor-in-chief, who replaced the controversial John Strugnell, describes his personal challenges in this demanding assignment; Sidnie White Crawford, now a leading scroll scholar in her own right, was just a kid back then but with a view from the inside; and Martin Abegg, who was also just a young graduate student […]

You have already read your free article for this month. Please join the BAS Library or become an All Access member of BAS to gain full access to this article and so much more.

Already a library member? Log in here.

Institution user? Log in with your IP address or Username

Footnotes

Avi Katzman, “Chief Dead Sea Scroll Editor Denounces Judaism, Israel; Claims He’s Seen Four More Scrolls Found by Bedouin,” BAR 17:01.

Queries & Comments, BAR 17:02.

Hershel Shanks, “John Strugnell: For the Man, Compassion; For His Views, Contempt,” BAR 17:01.

Hershel Shanks, “Debate on Enoch Stifled for 30 years while Scholar Studied Dead Sea Scroll Fragments,” Bible Review 03:02.

“Sensationalizing Gnostic Christianity,” First Person, BAR 32:04.

Endnotes

F. M. Cross, D. W. Parry, R. Saley, E. Ulrich, Qumran Cave 4.XII: 1-2 Samuel (DJD XVII; Oxford: Clarendon, 2005).