Nine years, almost to the day, after Roman legionaries destroyed God’s house in Jerusalem, God destroyed the luxurious watering holes of the Roman elite.

Was this God’s revenge?

That’s not exactly the question I want to raise, however. Rather, did anyone at the time see it that way? Did anyone connect the eruption of Mt. Vesuvius in 79 C.E. with the Roman destruction of Jerusalem in 70?

First the dates: The Romans destroyed the Second Temple (Herod’s Temple) on the same date that the Babylonians had destroyed the First Temple (Solomon’s Temple) in 586 B.C.E. But the exact date of the Babylonian destruction is uncertain. Two different dates are given in the Hebrew Bible for the destruction of the First Temple. In 2 Kings 25:8 the date is the 7th of the Hebrew month of Av; Jeremiah 52:12 says it occurred on the 10th of Av. The rabbis compromised and chose the 9th of Av (Tisha b’Av). That is the date on which observant Jews, sitting on the floor of their synagogues, still mourn the destruction of the First Temple, Solomon’s Temple, in 586 B.C.E. and the Second Temple, Herod’s Temple, in 70 C.E.

The exact corresponding date in the Gregorian calendar is also a bit uncertain. According to the translator of the authoritative translation of Josephus, the ancient historian who gives us our most detailed (if sometimes unreliable; see sidebar) account of the Roman destruction of the Temple in 70 C.E., it occurred on August 29 or 30.1 Others place it earlier in the month.

The eruption of Mt. Vesuvius that destroyed Pompeii, Herculaneum, Stabia and other nearby sites occurred, according to most commentators, on August 24 or 25 in 79 C.E. According to Seneca, the quakes lasted for several days.

But the dates are close enough to raise the question: Were these two catastrophic events connected, at least in the mind of some observers?

The volcanic eruption of Vesuvius has been graphically described by Dio Cassius in his Roman History:

The whole plain round about [Vesuvius] seethed and the summits leaped into the air. There were frequent rumblings, some of them subterranean, that resembled thunder, and some on the surface, that sounded like bellowings; the sea also joined in the roar and the sky re-echoed it. Then suddenly a portentous crash was heard, as if the mountains were tumbling in ruins; and first huge stones were hurled aloft, rising as high as the very summits, then came a great quantity of fire and endless smoke, so that the whole atmosphere was obscured and the sun was entirely hidden, as if eclipsed. Thus day was turned into night and light into darkness … [Some] believed that the whole universe was being resolved into chaos or fire .… While this was going on, an inconceivable quantity of ashes was blown out, which covered both sea and land and filled all the air … It buried two entire cities, Herculaneum and Pompeii … Indeed, the amount of dust, taken all together was so great that some of it reached Africa and Syria and Egypt, and it also reached Rome, filling the air overhead and darkening the sun. There, too, no little fear was occasioned, that lasted for several days, since the people did not know and could not imagine what had happened, but, like those close at hand, believed that the whole world was being turned upside down, that the sun was disappearing into the earth and that the earth was being lifted to the sky.2

The tone is plainly apocalyptic. And indeed Dio seems to have had this in mind. In the next paragraph he notes that the eruption consumed the temples of Serapis and Isis and Neptune and Jupiter Capitolinus, among others. It is almost as if some supreme God was at work.

Seventeen-year-old Pliny the Younger was an eyewitness to the eruption and described it in terms similar to Dio’s. In two surviving letters to Tacitus, Pliny also gives an account of the death of his famous uncle Pliny the Elder, author of the renowned Historia Naturalis. Pliny the Elder was at Misenum in his capacity as commander of the Roman fleet when the eruption began. He set sail to save some boatloads of people nearer Vesuvius and headed toward Stabia—to no avail. All perished, including Pliny, as his nephew recounts:

Ash was falling onto the ships, darker and denser the closer they went. Now it rains bits of pumice, and rocks that were burned and shattered by the fire … Broad sheets of flame were lighting up many parts of Vesuvius; their light and brightness were the more vivid for the darkness of the night … Buildings were being rocked by a series of strong tremors and appeared to have come loose from their foundations and to be sliding this way and that. Outside, however, there was danger from the rocks that were coming down …

It was daylight now elsewhere in the world, but there the darkness was darker and thicker than any night … Then came the smell of sulfur, announcing the flames, and the flames themselves …onto the ships, darker and denser the closer they went. Now it rains bits of pumice, and rocks that were burned and shattered by the fire … Broad sheets of flame were lighting up many parts of Vesuvius; their light and brightness were the more vivid for the darkness of the night … Buildings were being rocked by a series of strong tremors and appeared to have come loose from their foundations and to be sliding this way and that. Outside, however, there was danger from the rocks that were coming down …

[Then] came the dust, though still lightly. I looked back [from his flight from Misenum] … We had scarcely sat down when a darkness came that was not like a moonless or cloudy night, but more like the black of closed and unlighted rooms. You could hear women lamenting, children crying, men shouting.3

Then comes the same apocalyptic tone that we saw in Dio:

There were some so afraid of death that they prayed for death. Many raised their hands to the gods, and even more believed that there were no gods any longer and that this was the one last unending night for the world … I believed that I was perishing with the world, and the world with me, which was a great consolation for death.4

Did anyone connect all this to the Jewish God? To the Roman destruction of the Jerusalem Temple?

In a conversation with Harvard’s Shaye Cohen about something else, I offhandedly asked him if he knew of any ancient source that made the connection between the Vesuvius eruption and the destruction of the Temple. I had already asked this of several other scholars, but none had any sources for me, although they said there must be some. Shaye, however, immediately replied, “Try Book 4 of the Sibylline Oracles.” He was right on.

Book 4 of the Sibylline Oracles is thought to be mostly Jewish oracles by a so-called sibyl (in Greek legend an aged woman who uttered ecstatic prophecies) that were composed shortly after the eruption of Vesuvius in 79. The oracles were preserved by Christians who believed they gave pagan testimony to the true religion and to Christ.5

Although composed after the event, it is written as a prediction:

An evil storm of war will also come upon Jerusalem

from Italy, and it will sack the great Temple of God …

A leader of Rome [Titus] will come … who will burn

the Temple of Jerusalem with fire [and] at the same time slaughter

many men and destroy the great land of the Jews.

…

When a firebrand, turned away from a cleft in the earth [Vesuvius]

in the land of Italy, reaches to broad heaven

it will burn many cities and destroy men.

Much smoking ashes will fill the great sky

and showers will fall from heaven like red earth.

Know then the wrath of the heavenly God.6

There is more—from Pompeii itself:

After the destruction, the site was subject to looting. And people who had managed to flee came back to see whether they could retrieve some of their possessions.

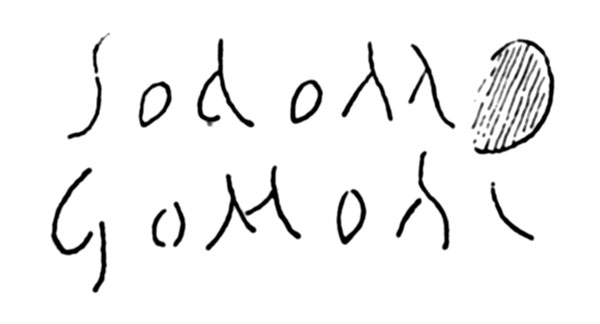

One such person came back to a house in an area of Pompeii designated today as Region 9, Insula 1, House 26. After having walked through the desolation of the city, he (unlikely to be a “she”) looked about and saw nothing but destruction where once there had been buildings and beautifully frescoed walls. Disconsolate and aghast, he picked up a piece of charcoal and scratched on the wall in large black Latin letters:

SODOM GOMOR[RAH].7

As he saw it, the divine punishment of these two cursed Biblical cities was echoed in the rain of fire on Pompeii.8

The inscription was found in a 19th-century excavation at the site. I went to Pompeii to see the place where it was discovered. (The inscription itself is in the stores of the Naples Archaeological Museum; it is nearly illegible at this time.) In the center of the insula (a kind of city block) where it was found is a beautifully preserved columned atrium. House 26 is like the others in the insula—dark, destroyed, with vestiges of paintings on the walls, but mostly nothing.

It would seem that this inscriptional reference to Sodom and Gomorrah was the work of a Jew, which leads to the question whether there were Jews living in Pompeii. An indication that the answer is yes is a painting found in excellent condition on the walls of another, more elegant house. It is a painting of the Judgment of Solomon, deciding which of two women is the mother of the baby (1 Kings 3:16–28). The painting is the earliest known depiction of a Biblical scene and was the subject of a BAR article a couple of years ago.a

But there may also be other evidence that a community of Jews lived at Pompeii.

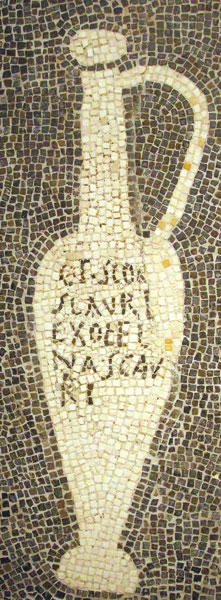

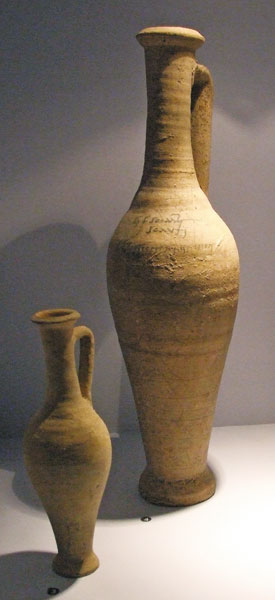

Garum was a very popular Roman delicacy, a fish sauce variously composed of different kinds of often-decomposed or fermented marine life and herbs and spices. Indeed, Pompeii was famous for its garum. According to Pliny the Elder, Pompeii “has a good reputation for its garum.”9 As if in confirmation of this observation, at least one store selling garum has been excavated in Pompeii. On the floor of the owner’s house (one Aulus Umbricius Scaurus) is a mosaic featuring labeled jars containing different kinds of garum.

Garum presented a problem for Jews, however—at least for those who kept the laws of kashrut (kosher laws). These Jews could not use garum that was made from fish without scales or from shellfish (see Deuteronomy 14:10 and Leviticus 11:10). Garum made from these products would not be kosher. Was there special kosher garum—garum made only from fish with scales?

The answer is yes, according to Pliny the Elder, who tells us that “another kind [of garum] is devoted to … Jewish rites, and is made from fish without scales.” Pliny obviously made a slip of the tongue here; he meant to say “fish with scales.” But it is clear that special garum, kosher garum, was indeed available to Jews.

And jars of kosher garum appear to have been found at Pompeii, although the matter is not without controversy. Among the garum amphorae from Pompeii several bear a label said to be kosher garum. The painted inscription on these jars consists of two Latin words, both incomplete:

GAR [or MUR]

CAST.

The first word could be completed as GAR[um] or MUR[ia]. Muria is also a kind of fish sauce, so it really doesn’t matter which it is.

The second word could be completed CAST[um] or CAST[imoniale]. Castum means “pure” or “chaste” or “innocent” or “spotless.” It could well refer to the purity of garum prepared for observant Jews. Castimoniale refers to bodily purity.10 But the inscription is on a jar of garum, so even if this is the correct reconstruction, it would seem to refer to a kind of special or pure garum.

In a recent, highly praised book on Pompeii, Cambridge University scholar Mary Beard concludes without qualification that this inscription was a designation for kosher garum. Beard refers to “a painted label advertising its contents as ‘Kosher Garum.’”11 There are some doubters, however.

The chief doubter is Hannah Cotton, a prominent scholar at the Hebrew University. In her publication of a garum jar excavated at Masada in Israel, she cites supposedly “grave arguments” against the notion that garum castum was intended for Jews.12 Pure garum, which is all that garum castum means, could be intended for other religious groups with food restrictions as well—the worshipers of Apis, Isis and Magna Mater, for instance. In this connection she cites an article by another distinguished scholar, Robert I. Curtis, professor of classics, now retired, at the University of Georgia and an authority both on Pompeii and garum.

I wondered about this. Did these pagan groups really have food laws similar to the Jews’? I contacted Professor Curtis, who wrote me: “[Professor Cotton] apparently misinterpreted what I had written. Perhaps I wasn’t very clear.” Curtis continued: “The ancient sources on the cult practices of these pagan mystery cults are not very forthcoming, and the information that we do have is primarily from authors hostile to them. So, 100% certainty on matters regarding fasting and abstinence is impossible … I am not aware that followers of Isis, Magna Mater, etc. exercised restrictions of this kind [i.e., similar to the Jews]. They did, however, have abstinences of particular foods for limited periods of time, usually during recurring festivals … Recognizing a sauce as castum, therefore takes on more importance for [Jews]. Fish sauce producers, if they cared at all about catering to a specific clientele, even a small one, could, I think, have directed a specific product to them …”

Ever the careful scholar, however, Curtis nevertheless concludes that “I am still not able to state unequivocally that the expression garum castum was meant exclusively for Jews.”13 So the matter is not free from all doubt,14 but the presence of kosher garum at Pompeii is highly likely.

In any event, if there were Jews at Pompeii—and it seems there were—they may well have made the connection between the events of 70 and 79: God was indeed taking revenge against the Romans for destroying his Temple.

MLA Citation

Footnotes

1.

Theodore H. Feder, “Solomon, Socrates and Aristotle,” BAR 34:05.

Endnotes

1.

Jewish War, 6.244, 250, notes, tr. H. St. J. Thackeray.

2.

Dio Cassius, Roman History, 66.22.3–23.5.

3.

Pliny the Younger, Letters, 6.16, 6.20.

4.

Pliny the Younger, Letters, 6.20.

5.

See John J. Collins, “Sibylline Oracles,” Anchor Bible Dictionary (New York: Doubleday, 1992).

6.

[vv. 115–116, 125–127, 130–135] John J. Collins, “Sibylline Oracles—A New Translation and Introduction,” in James H. Charlesworth, ed., The Old Testament Pseudepigrapha (New York: Doubleday, 1983), p. 387. Collins makes explicit in a footnote the clearly implied connection between the two events.

7.

See Carlo Giordano and Isidoro Kahn, The Jews in Pompeii Heculaneum, Stabiae and in the Cities of Campania Felix 3rd ed., Wilhelmina F. Jashemski, trans. (Rome: Bardi Editore, 2003), pp. 75–76.

8.

Another more ambiguous inscription was also found in the destruction of Pompeii, in Region 9, Insula 11, House 14, reading in Latin letters “Poinium Cherem.” Cherem could mean “excommunication” or “destruction” if the first letter is a het in Hebrew. But even cherem with a het could also mean consecrated to God, or holy. If the first meaning of cherem with a het was intended, this inscription, too, could refer to the destruction of Pompeii as God’s absolute condemnation of Pompeii for the prior Roman destruction of his Temple. The preceding Poinium presents a problem, however. Poinium could be the Latin form of a Greek noun ending in –nion, that is, poimnion, meaning “flock.” And the ch in cherem could also be a Latin transcription of Hebrew chaf as well as het, in which case cherem would mean “vineyard.” The writer of the inscription may have been using the imagery of the prophet Isaiah: Israel is “the flock of the Lord” (Isaiah 40:11); similarly, “the vineyard (cherem) of the Lord of Hosts is the House of Israel” (Isaiah 5:7). “In this sense the cherem of the inscription could be understood as the name of the Jewish community at Pompeii …” (Giordano and Kahn, The Jews in Pompeii, Herculaneum, Stabiae and in the Cities of Campania Felix, p. 99). On the other hand, poinium could also be understood as Greek poine, similar in meaning to the Latin poena; that is, punishment, which would fit nicely with the meaning of cherem as “destruction” or “excommunication.” See Giordano and Kahn, pp. 89–103, for an extended discussion of these issues.

9.

Natural History, Book XXXI, pp. 931ff.

10.

I am indebted to Philip King for these translations from the Latin.

11.

Mary Beard, The Fires of Vesuvius (Cambridge, MA: Harvard Univ. Press, 2008), p. 24. See also p. 302.

12.

Masada II, The Latin and Greek Documents, (Jerusalem: Israel Exploration Society, 1989), p. 166.

13.

We have posted the full text of Professor Curtis’s response to me online at www.biblicalarchaeology.org/e-features.

14.

Professor Cotton also cites in support of her contention J.B. Frey, “Les Juifs a Pompei,” Revue Biblique 32 (1933), p. 365. Frey makes similar arguments to that of Curtis. Moreover, he is unwilling even to admit that there were Jews in Pompeii or even that the quotation from Pliny demonstrates that the Jews had a special kosher garum. His argument decisif is that “aucune garantie donee par des paiens n’aurait suffi a des Juifs, car en pareille matiere la parole des Gentils ne pouvait faire foi” (at p. 373).