The Pentateuch, or the five books of Moses—Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers and Deuteronomy—how was it formed? What is the history of its composition?

The traditional view of both Judaism and Christianity has been that it was written by Moses under divine inspiration.

As early as the 12th century, however, the Jewish commentator Ibn Ezra raised questions about certain references that seemed to point unmistakably to events that occurred or circumstances that existed much later than Moses’ time. Some of the difficulties besetting the traditional dogma—for example, the circumstantial account of Moses’ death and burial at the end of Deuteronomy—are obvious to us today. This was not the case in the early modern period, however. Richard Simon, a French Oratorian priest now regarded as one of the pioneers in the critical study of the Pentateuch, discovered this the hard way when he published his Histoire critique du Vieux Testament (Critical History of the Old Testament) in 1678. Simon tentatively attributed the final form of the Pentateuch to scribes from the time of Moses to the time of Ezra. Simon’s work was placed on the Roman Catholic index, most of the 1,300 copies printed were destroyed and Simon himself was exiled to a remote parish in Normandy.

One clue modern source critics still employ to distinguish between different sources or strands in the biblical text is the use of different divine names. This technique was first employed more than 250 years ago. Some biblical passages seem consistently to refer to God by the name Yahweh; others, by Elohim. The first person to distinguish between different sources on the basis of the divine names used in them was an obscure German pastor named Witter whose work, published in 1711, went unnoticed to such an extent that it was only rediscovered about 60 years ago. The French scholar Adolphe Lods came across the book, written in Latin, while researching the early stages of Pentateuch criticism in 1924. Interestingly enough, Witter did not abandon the dogma of Mosaic authorship but simply suggested that Moses used sources recognizable by the generic divine name Elohim, as distinct from Yahweh. Yahweh was the name revealed to Moses in the wilderness (Exodus 3:13–15; 6:2–3).

This idea was developed further, but apparently independently of Witter, by a French physician, Jean Astruc. In 1753 Astruc, on the basis of his study Genesis, identified three sources in the text: the Elohistic source (using the name Elohim), the Jehovistic source (using the name Yahweh—or Jehovah in its Germanic form) and a remaining source that could not be attributed to either of these sources. These mémoires, as Astruc called the sources, were put together by Moses and resulted in the Pentateuch as we have it.

Astruc’s formulation was taken over and further refined by Johann Gottfried Eichhorn, author of the first scientific Introduction to the Old Testament (1780). Eichhorn maintained that Moses was the author of the Pentateuch, but Eichhorn did so as a child of the Enlightenment—not for dogmatic reasons but because he believed that Moses began life as an Egyptian intellectual and then became the founder of the Israelite nation.

By the beginning of the 19th century, most Bible critics outside of the conservative ecclesiastical mainstream agreed that the Pentateuch was the result of a long process of formation, and that it was made up principally of two types of material indentified in general by their respective use of the divine names Elohim and Yahweh.

Later, the Elohist source (E) was subdivided into the Elohist (E) and another strand designated as the Priestly source (P). In its first formulation the P source was regarded as the product of priestly authors writing sometime after the Babylonian Exile 586 B.C.), when the priests assumed a dominant role in the religious life of the community. Generally, the E source was thought to be earlier than the J source, largely on the ground that, according to one biblical tradition (Exodus 6:2–3), the personal divine name Yahweh was first revealed to Moses; prior to Moses’ time, God was referred to as Elohim.

One problem—and it is still a problem today—is apparent: the conclusions were drawn primarily on the basis of Genesis. Today we recognize that an explanation that seems to work well with one section of the Bible—for example, the primeval history recounted in Genesis 1–11—might not work so well with another section—for example, the Exodus story in Exodus 1–15.

Closer study of key passages, beginning with the work of German theologian Wilhelm de Wette in 1807, led to a reversal of the chronological order in which the sources were arranged, so that J was dated earlier than. E. De Wette also made a significant contribution by recognizing Deuteronomy as a separate source and identifying it with the book discovered, according to the Bible, during repair of the Temple fabric in the 22nd year of the reign of King Josiah (622 B.C.), the last great king of Judah. King Josiah’s religious reforms, as recounted in 2 Kings 22–23, included the disestablishment of the “high places” and an insistence on the exclusiveness of the single central sanctuary in Jerusalem. Since this corresponds closely with the legal viewpoint in Deuteronomy (especially 12:1–14), de Wette was able to identify the fifth book of the Pentateuch as the book the Bible tells us was discovered in the cleansed Jerusalem Temple or, as de Wette maintained, as the book that was “planted” in the temple by the priests. De Wette’s hypothesis, which won wide acceptance, was to become a pivotal point in the study of the Pentateuch, since it made possible a distinction between earlier legislation not in accord with Deuteronomy and later enactments that presupposed it.

The ground was thus prepared for the classic statement of the documentary hypothesis developed by the Strasbourg professor Eduard Reuss (1804–1891), together with his student and friend Karl Heinrich Graf (1815–1869), and formulated with unsurpassed brilliance and clarity in Julius Wellhausen’s Prolegomena to the History of Israel in 1883. This so-called higher criticism was carried on for the most part in Germany, which has always been the heartland of biblical and theological study in the modern period. In the English-speaking world, where conservative ecclesiastical influences were more in evidence, the documentary hypothesis took root much later. As late as 1880, the vast majority of biblical scholars in Britain and America supported the Mosaic authorship of the Pentateuch.

The literary analysis embodied in the higher criticism not only attempted to explain the compositional history of the Pentateuch, it also served as the basis for reconstructing the evolution of religious ideas in Israel and early Judaism. The earliest sources, J and E (which Wellhausen wisely did not try to distinguish too systematically), were thought to reflect a more primitive stage of nature religion based on the kinship group. Deuteronomy (D), on he other hand, recapitulated prophetic religion; at same time, Deuteronomy brought the age of prophecy to an end by the issuance of a written law. For most scholars in the 19th century, the prophets, with their elevation of ethics over cult and their unmediated approach to God, represented the apex of religious development. Accordingly, after the age of prophecy came to an end, there was nowhere to go but down. The last stage Israel’s religious development, reflecting a theocratic world view, found expression in the, Priestly source (P) from the Exilic or early post-Exilic period (sixth-fifth century B.C.).

This kind of evolutionism, which drew heavily on German Romanticism and the philosophy of Hegel, is fortunately no longer in favor. What remains as a task for scholarship today is a more careful evaluation of the arguments on which the documentary hypothesis is based.

Since the publication of Wellhausen’s Prolegomena it has become apparent that all four strands of the Pentateuch—J, E, P and D—are themselves composites. But the attempt to break them down into their components (J1, J2, for example) has led increasingly to frustration and has contributed to the current widespread disillusionment with the docmentary hypothesis.

There have always been those who either questioned one or another aspect of the documentary hypothesis or, like the Jewish scholars Yehezkel Kaufmann and Umberto Cassuto, have rejected it outright. In the last decade, however, doubts have begun to be raised by biblical scholars standing in the critical mainstream. A more detached investigation of key passages, especially in Genesis, has suggested that the criteria for distinguishing between the “classical” sources (J, E, P, D and their subdivisions) can no longer be taken for granted. The distinction between J and E (J’s ghostly Doppelgänger) has always been problematic, and there has never been complete consensus on the existence of E as a separate and coherent narrative. In the years shortly after World War II, the Yahwist(J) achieved a high degree of individuality as the great theologian the early monarchy (tenth or ninth century B.C.), largely due to the influential work of the Heidelberg Old Testament scholar Gerhard von Rad. During the last decade, however, growing doubts have emerged about the date, the extent and even the existence of J as a separate and cohesive source spanning the first five or six books of the Bible. Similar if less insistent doubts have been voiced about the date of the Priestly source (P) and its relation to earlier traditions in the Pentateuch

The net result is that the earlier consensus, which was never absolute, has suffered erosion, while no paradigm capable of replacing the classical documentary hypothesis of J, E, P and D has yet emerged. Some continue to pay it lip service but do not use it, a few—for example, the prominent German Old Testament scholar Rolf Rendtorff—have abandoned it altogether.

In short, the critical study of the sources of the Pentateuch, which has been at the forefront of Old Testament studies since the late 18th century, seems to have lost its sense of direction in recent years. Many Old Testament scholars, especially in the English-speaking world, excited by their discovery of the New Criticism (no longer new after about half a century), have lost interest in investigating sources and original settings of biblical texts. The same goes for those who are applying structuralist theory to biblical narrative, since the essence of structuralist literary theory is to read a text as a closed system. A more traditional approach to the biblical text, which goes under the name of canonical criticism (represented preeminently by Professor Brevard S. Childs of Yale Divinity School), insists on the final canonical form of the Pentateuch, rather than its hypothetical sources, as the proper object of theological exposition. These influences have resulted in a great diminution of interest in the kind of literary archaeology that produced the documentary hypothesis in the 19th century.

Those who are still concerned with the problem are desperately seeking for new answers. For example, many now question the earlier view that J (or Yahwist, as he is often called) was an author with distinctive theology. In reaction against this view, many scholars are now questioning the unitary and cohesive nature of this source and no longer see it as the foundation of the story line in the Pentateuch. As suggested earlier, doubts continue to be entertained both about the existence of the Elohist(E) as a distinct strand, once thought to be a source parallel to J, but originating in the northern kingdom of Israel sometime after the death of Solomon. P has survived recent attacks on the documentary hypothesis best of all, due to its highly distinctive language, and its fondness for genealogies and exact chronological indications. But now scholars recognize that P too is a composite document. It too has gone through a number of compositional stages involving editing (reaction) and expansion of the text. There is even debate as to whether P should be considered an, independent narrative source or a reworking of earlier traditional material.

Moreover, other lines of inquiry have been found to be more promising than refined efforts at source criticism: for example, the study of the literary character and structure of the text and the social origin of small textual units (form criticism), the identification and tracing of the growth of traditions embodied in the texts (tradition history), the identification of editorial procedures in the development of the text and their ideological or theological presuppositions (redaction history).

To obviate any possible misunderstanding, let me emphasize that there is no question of a return to a pre-critical reading of the biblical text. If the documentary hypothesis is in crisis, the question for those still interested in the formation of the Pentateuch, is whether the hypothesis is salvageable and, if not, what might take its place. But it remains clear that we cannot simply jettison a historical-critical approach to the biblical text.

Perhaps we can best illustrate the problems and possibilities that may emerge by examining one section of the Pentateuch, the Flood story (Genesis 6–9). Any conclusions we reach will have to be tentative and will not necessarily apply to other biblical texts. However, we would expect to pick up some things worth pursuing throughout the Pentateuch.

With few exceptions, documentary hypothesis scholars are agreed that the Flood story, like the rest the primeval history in Genesis 1–11, is a combination of two strands: the Yahwist, or J, source from the early Israelite monarchy, (tenth or even ninth century B.C.) and the Priestly, or P, source from the Exilic or early post-Exilic period, some four centuries later. Again, with few exceptions, they regard the earlier strand, J, as a source for the later strand, P. That is, P incorporated J and, at the same time, gave the narrative its final form, which it still retains.

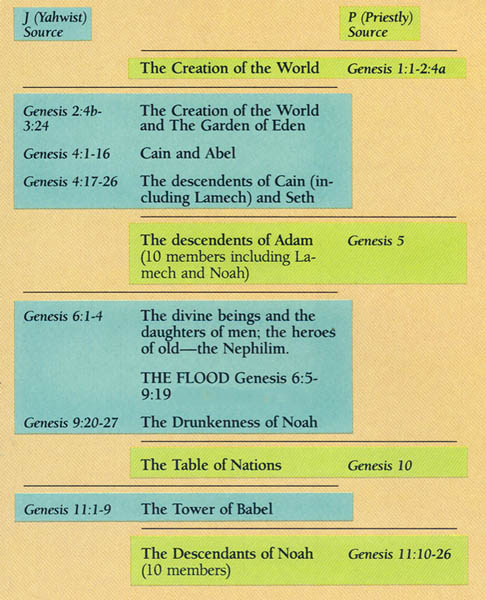

In the final sidebar to this article, we show the way the primeval history (Genesis 1–11) is generally divided by documentary hypothesis scholars. Although the Flood story is there listed as a composite of the two sources, there are enough repetition in the story to allow us to draw up two roughly parallel versions characterized by distinctive and recurring linguistic and stylistic differences. We shall focus here on one short passage in the Flood story to illustrate how the two strands of the Flood story can be separated. It is the account of Noah’s entry into the ark. The lines in the following chart have been divided so that parallel aspects of each version are opposite one another. Italics are used to identify language that is identical almost identical in both sources.

|

J (Yahwist) Source |

P (Priestly) Source

|

|

(Genesis 7:7–10) |

(Genesis 7:13–16)

|

|

Noah, his sons, his wife and his daughters-in-law with him went into the ark to escape the waters of the Flood. |

On that very day Noah, the sons of Noah, Shem, Ham and Japhet, the wife of Noah, and his three daughters-in-law went into the ark,

|

|

Of clean animals and of animals that are not clean, of fowl and everything which creeps on the ground |

together with every living thing according to its kind, and every animal according to its kind, and every crawling thing which creeps on the earth according to its kind; and every fowl according to its kind;a

|

|

two by two they went to Noah into the ark, male and female as God had commanded Noah |

they went to Noah into the ark, two by two, from all flesh which has in it the breath of life those who entered, male and female from all flesh, went in as God had commanded him

|

|

After seven days the waters of the Flood came upon the earth. |

(Noah was 600 years old when the Flood of waters came upon the earth, vs. 6)

|

Note that the P text is about a third longer than J and yet about half of P is verbally identical with J. Repetition does not, of course, in itself prove plurality of authorship. But when the repetitions amount to parallel versions, each with distinctive and recurring linguistic, stylistic and thematic features, and when this phenomenon is found repeatedly throughout the Pentateuch, the likelihood of plurality of authorship is no longer a mere possibility, but a strong probability. Note that the only significant thematic difference between the versions quoted above is that one (J) distinguishes between clean and unclean animals and the other (P) does not. Similarly, after the Flood, J records Noah’s sacrifice on the purified earth (Genesis 8:20–21), but P does not. Assuming the existence of a Priestly source, this is what we would expect, since in Leviticus 1–7 and 11 attributed to P), P is careful to note that the laws governing sacrifice and ritual purity were transmitted only much later, to Moses at Sinai. Therefore they were not incorporated into P’s Flood story in Genesis

It is on the basis of this kind of testing—and demonstration of internal consistency—carried out over the entire Pentateuch, that the existence of parallel versions has been established with a fair degree of probability

At this point, however, problems begin to arise with the classic formulation of the documentary hypothesis, especially with the way it attempts to explain the relationship between different sources and the process by which they were combined to give us the final text. I will illustrate some of these problems in connection with the Flood. (The chart in the sidebar “Disentangling the Sources of the Flood Story” lists the traditional divisions between J and P for the entire Flood story.)

1. P’s Flood story is a complete and logically coherent narrative, beginning with the chapter heading “These are the generations of Noah” (6:9) and concluding with Noah’s death (9:29). This is not true of the J version: The ark is introduced suddenly and without explanation (7:1); the story goes directly from Noah looking out of the ark, to the sacrifice on dry land (8:13b, 20).

Consider the interesting little detail that after Noah entered the ark, “Yahweh shut him in [the ark]” (7:16b). The documentary critics have assigned this statement to J, but it does not fit there in J’s version; according to J’s version, this statement comes too late because the Flood is already underway (7:7–10, 12), so Noah must have been shut in earlier in the P version. The statement that Yahweh shut Naoh in the ark follows after his entry into the ark; and the statement is intelligible only as a footnote explaining how the ark could have remained watertight (6:14) after Noah and his family had gone aboard. In its generally accepted form, the documentary hypothesis encounters similar difficulties throughout Genesis 1–11.

2. A much stronger case can be made for P as internally consistent and well organized narrative source than for the balance of the narrative in Flood story. The same is true throughout the primeval history. The non-P material in Genesis 1–11 has nothing like the same consistency.

3. Arguments for a very early date for the non-P material are far from conclusive. In his standard Old Testament, An Introduction (1965), German Bible scholar Otto Eissfeldt, who expounds the documentary hypothesis with his own variations, provides only one argument for putting J in the period the early monarchy. That is its “enthusiastic acceptance of agricultural life and of national-political power and status” (p. 200). Whatever validity this criterion might have for other parts of the Pentateuch, however, it surely does not apply to Genesis 1–11; in the passages of the primeval history generally attributed to J, the author emphasizes not the acceptance of agricultural life, but the curse on the soil (Genesis 3:17), banishment from the Garden of, Eden and the divine repudiation of human pretensions (for example, the Tower of Babel story).“National-political power and status” is hardly endorsed.

4. In addition, scholars have begun to notice that some key passages attributed to J—the Garden of Eden story (Genesis 2:4–3:24) and the preface to the Flood story (Genesis 6:5–8)—have a strong sapiential flavor; that is, a flavor characteristic of late post-Exilic wisdom literature that reached its flowering in biblical books like Job and certain sections of Proverbs. Moreover, the supposedly J portion of Genesis 1–11 even makes use of the terminology found in late wisdom writings. For example, “the tree of life” (Genesis 3:22, 24) is mentioned in Proverbs (3:18, etc.) and nowhere else, and the word for the mist or spring that watered the ground (Genesis 2:6, ’ed in Hebrew) occurs in Job 37:27 and nowhere else.

5. This brings us to our final question, one not often asked by documentary critics: How did the narrative reach its final form? The general assumption has been that the Priestly author or authors took over, edited and expanded the early material, resulting in the Pentateuch as we have it. But all of this other evidence, including the late reworking of what is supposedly J, seems to point in a different direction. Moreover, if P had been responsible for the final version of the text, it is inconceivable, for example, that P would have left in the distinction between clean and unclean animals in the Flood story because the distinction, as noted earlier, was not introduced until Moses’ time (see Leviticus 11). For the same reason, P only uses the divine name Yahweh after it had been revealed to Moses (Exodus 6:2–3). In the Bible as finally transmitted, non-P materials, presumably from an earlier tradition, have Yahweh being venerated under that name from the very beginning (Genesis 4:26). Why would P leave such a reference in the text if he was its final editor? Similar problems can be found throughout the Pentateuch. For example, it is hard to believe that the Priestly source, which understandably venerates Aaron as the ancestor of the priesthood, would have left in the Golden Calf incident (Exodus 32) in which Aaron plays at best a dubious role. We are therefore led to think that there must have been a still later editorial stage in the development of the text that built up the history of early humanity around a basically Priestly work, but supplemented it with other available narrative material. The precise details of the process are obviously obscure. But the point is that the documentary hypothesis in its traditional formulation does not fully explain the development of the biblical text.

On the other hand, you may ask, what difference does it make? Why does it matter? It is obviously possible to read and appreciate the Flood story without all this critical reconstruction of its literary history. People have been doing this for centuries. What is the point of a historical-critical reading of biblical texts? What are its advantages over other methods, e.g., literary, allegorical, midrashic, formalist, structuralist, etc.? People are increasingly asking this question, not only because the academic study of the Bible has had relatively little impact outside the academy (biblical scholars generally write for each other), but also because critical scholarship has tended to assume that this is the only way to read a biblical text.

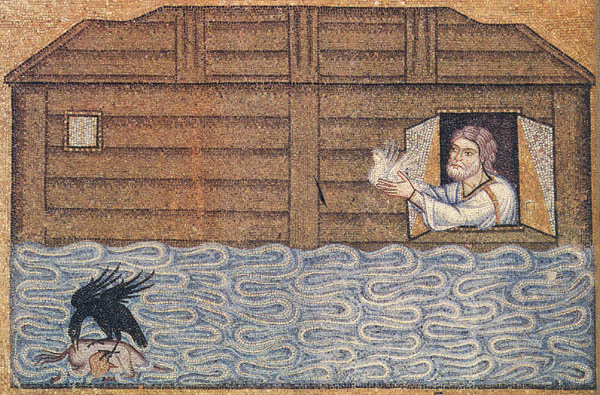

One answer is that the realization that the Flood story has a literary history will at least eliminate a simplistic approach to the historicity of the text—of a kind that has recently led to yet another expedition to scale Mt. Ararat in search of the ark. To put it differently, we will have to face the literary problem before we can even raise the issue of the story’s possible accuracy as a historical document. Moreover, the literary history of the Flood story is not confined to the Bible. The biblical Flood story is itself rather late version of a narrative theme often copied and much developed in the Near East over an enormous period of time. We know it, for example, in a pre-biblical form from the 11th tablet of the Gilgamesh epic. In 1914 a substantial fragment of a much earlier Sumerian version of the Flood story was published. Essentially the same version appears in a shorter form in a history of Babylon written by Berosus, a Babylonian priest, in the third century B.C. All of this material must be taken into account in interpreting and reconstructing the literary history of the biblical text. As the philosopher R. G. Collingwood pointed out a long time ago, the first question to ask is not “Did it really happen?” but “What does it mean?”

Admittedly, the object of historical-critical analysis has never been the esthetics of the text. The aim of historical-critical analysis has rather been to get at the historical, social and religious realities that generated the text. In this sense, the text is a point of access to the religious experience of Israel at the time of writing. If, for example, the Priestly core narrative of the Flood comes from the time of the Exile or shortly after, it can be expected to reflect aspects of religious thought in Israel at that time. Only in the P source of the Flood story, for example, does God make a covenant with all humankind in the person of Noah (Genesis 9:8–17). This is a quite remarkable breakthrough in religious thinking, prompted by the entirely new situation created by loss of Israel’s national independence in 586 B.C., followed by the Babylonian Exile. We could not understand this breakthrough in the same way if we could not attribute the passage to an Exilic or post-Exilic source.

The point, then, is that there are aspects of religious experience and levels of meaning in biblical texts that cannot easily be understood without a historical-critical approach of some kind. It is not the only way to read the Bible, but it has an important part to play. It is true that the documentary hypothesis has increasingly been shown to have serious flaws, but it is perhaps too early to jettison it entirely. Our task is to find better ways of understanding how the biblical narrative was generated without writing off the real advances of our predecessors.