If you want to understand how archaeologists think, how they reason, how they work, how they interpret finds—and why they sometimes disagree—you will enjoy this discussion among four prominent archaeologists who know as much about Qumran and its excavation as can be known today.

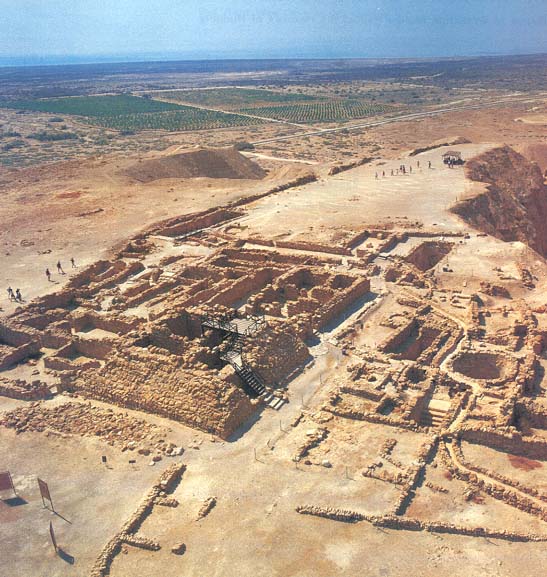

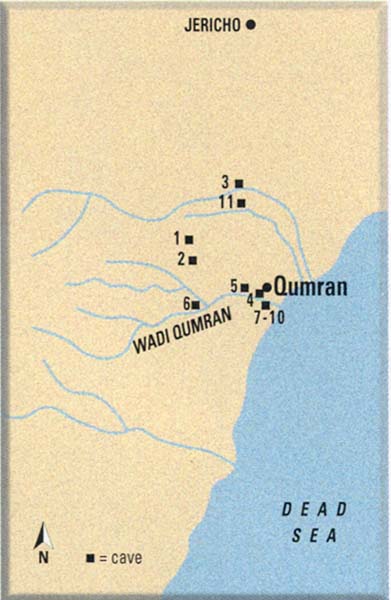

Long associated with the Dead Sea Scrolls found in nearby caves, Qumran was excavated between 1951 and 1956 by the late Father Roland de Vaux of the École Biblique et Archéologique Française in Jerusalem. De Vaux died in 1971 without publishing a final report.

For some, Qumran is the key to understanding the scrolls. But for everyone it is a fascinating site in its own right as scholars struggle to understand it—and to learn from it.

The participants in this discussion, three Israelis and an American, are all field archaeologists, or dirt archaeologists, as they are sometimes called. Joseph (Yossi) Patrich is associate professor of archaeology at the University of Haifa; Hanan Eshel is senior lecturer in archaeology at Hebrew University and Bar-Ilan University; Yizhar Hirschfeld is lecturer of classical archaeology at Hebrew University; and Jodi Magness is associate professor of classical and Near Eastern archaeology at Tufts University. BAR editor Hershel Shanks moderates the discussion, which was held in Jerusalem last summer.

Shanks: I would like to begin our discussion by putting the scrolls aside, by discussing the site of Qumran as if the scrolls didn’t exist. How would we interpret Qumran if there were no scrolls? I take it we would all agree that it’s a Jewish settlement, is that right?

All: Yes.

Shanks: How do we know it’s a Jewish settlement?

Eshel: Because of the ritual baths [in Hebrew, mikva’ot].

Patrich: And because of the Hebrew ostraca [inscribed potsherds] found at the site with Jewish names written on them.

Shanks: What about geography?

Hirschfeld: It is part of Judea in the late Second Temple period [37 B.C.E.–70 C.E.] and not far from Jerusalem.

Eshel: We also have a lot of stone vessels.

Shanks: Why is that significant?

Eshel: Stone vessels are typical of Jews who kept the purity laws. Stone vessels do not become impure.

Shanks: Why?

Eshel: Because that is what the Pharisaic law decided. Stone doesn’t have the nature of a vessel, and therefore it is always pure.

Shanks: Is that because you don’t do anything to transform the material out of which it is made, in contrast to, say, a clay pot, whose composition is changed by firing?

Eshel: Yes. Probably. Stone is natural. You don’t have to put it in an oven or anything like that. Purity was very important to Jews in the late Second Temple period.

Shanks: Hanan [Eshel], you mentioned ritual baths. How can you be sure they are ritual baths and not cisterns?

Eshel: In a cistern you have a small entrance and a very large area where the water is stored. In the mikva’ot at Qumran, we find steps leading all the way down to the bottom of the pools. They are not swimming pools. You have features typical of ritual baths: The last step is wide and also very deep. These are typical features of ritual baths in Jerusalem—[Israeli archaeologist] Ronny Reich collected them in his dissertation1—and all of these features are found in the ritual baths in Qumran. I think there is no question that what we find in Qumran are ritual baths.

Patrich: If you find a basin with steps going down, how else can you interpret it? If the main idea would have been to store water, then why lose the volume of water by constructing steps? If the idea is to construct a cistern, then you would construct it to hold as large a quantity of water as possible.

Hirschfeld: There are at least two basins at Qumran that we agree are reservoirs and not mikva’ot. The round one and the large rectangular one. The rest are probably mikva’ot. But the largest mikveh is quite unique [because of its size]. It is probably a mikveh because of the steps. But we should think about the reason for such a large mikveh.

Shanks: How did they get their water in this forlorn place?

Eshel: An aqueduct took the water from the nearby wadi. They built a dam in the wadi as it flows through the limestone cliffs, and in this way they shifted the water from the wadi into the aqueduct.

Magness: The water comes from flash floods.

Shanks: How often does it rain?

Magness: Not very frequently, but when it does rain, a lot within a short period of time, the water flows in the form of flash floods down to the Dead Sea.

Shanks: Is the limestone porous?

Magness: What you have on top of the limestone is chalk, which is not porous.

Shanks: Is it like a waterfall?

Magness: Yes, there is a waterfall right behind the site.

Eshel: There are actually four waterfalls as the water flows down the cliffs to the Dead Sea. The dam—and the beginning of the aqueduct to the site—begins at the bottom of the second waterfall.

Magness: The dam raised the level of the water to the point that it would flow into a channel that led to the site. You only need one flash flood a winter to fill up all the pools at Qumran. So it doesn’t matter if it doesn’t rain that often. It was the same principle, by the way, at Masada.

Eshel: All the desert fortresses of the late Second Temple period had this kind of aqueduct.

Hirschfeld: The water capacity of the cisterns and mikva’ot at Qumran is something like 1,200 cubic meters. [Günter] Garbrecht and [Yehuda] Peleg published an article listing the capacity of the water systems in other desert fortresses. And Qumran is among the lowest on the list.2

Magness: In his book on Masada, Yadin wrote that each of the big cisterns there had a capacity of about 4,000 cubic meters—much more than Qumran.

Shanks: So you’re saying that the amount of water available at Qumran was not really above average for these desert settlements?

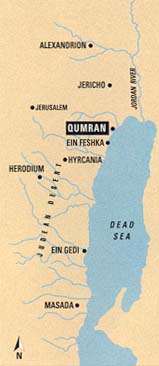

Eshel: Right. And the other desert fortresses had much better aqueducts and much larger cisterns. When you compare Qumran to the other fortresses of the Judean desert—starting with Alexandrium in the north, Duk, Hyrcania, Herodium, Masada, and Machaerus, east of the Jordan—then Qumran is not so unique. It’s not as good as the rest as far as collecting those floodwaters goes.

Shanks: You’ve all been using the term “desert fortresses.” When our readers hear the word “fortress,” they think of a military occupation of a site that is built to be defended by the military personnel inside. Is that what you mean by a fortress?

Hirschfeld: No. We use the term fortresses of the Judean desert as almost a nickname. Most of them were fortified palaces, the private complexes of the kings of Judea. Qumran, however, was not one of this family of buildings but a fortified settlement.

Eshel: In 1975 Yoram Tsafrir published an article about the desert fortresses of Judea, mentioning all of them, providing a bibliography, giving the historical sources for them.3 They are a group, a family of fortresses. But that didn’t include Qumran.

Shanks: He wrote about the royal Hasmoneana and Herodian [37 B.C.E.–70 C.E.] fortresses.

All: Yes, yes.

Eshel: All of them have special common features, such as aqueducts and cisterns.

Shanks: But all of them are different from Qumran in that they are royal fortress palaces. Qumran is not.

Magness: Yes, and all of them are on mountaintops.

Hirschfeld: They are very different from Qumran. And all of them are referred to in surviving historical sources. Qumran is not.

Magness: The only thing Qumran has in common with these other sites is the fact that it is in the Judean desert and it is a Jewish site of the same period. But it has nothing in common in terms of the architecture, the layout, the pottery, the small finds. There are no similarities at all.b

Patrich: We need to be clear about what we mean by fortresses. These Hasmonean and Herodian desert fortresses are unique. They were royal residences. But there were also many military posts all over the country. Contrary to Norman Golb’s suggestion,4 there is no similarity between Qumran and these other military fortresses.c They have completely different characteristics.

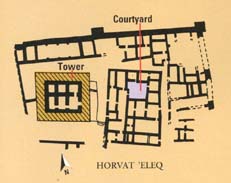

In my opinion, the original function of Qumran was more like what Yizhar [Hirschfeld] has suggested. In my opinion, the correct comparison, architecturally, is with fortified farms. They are known all over Judea from the Hasmonean and Herodian periods. This is what he has pointed out to all of us.

Shanks: What you are saying is, Qumran, architecturally, is not a military fort but a fortified farm, and it’s similar to many others that existed at this time all over the country, is that right?

Patrich: That is what Yizhar [Hirschfeld] has shown—architecturally—and he should be credited with the suggestion.

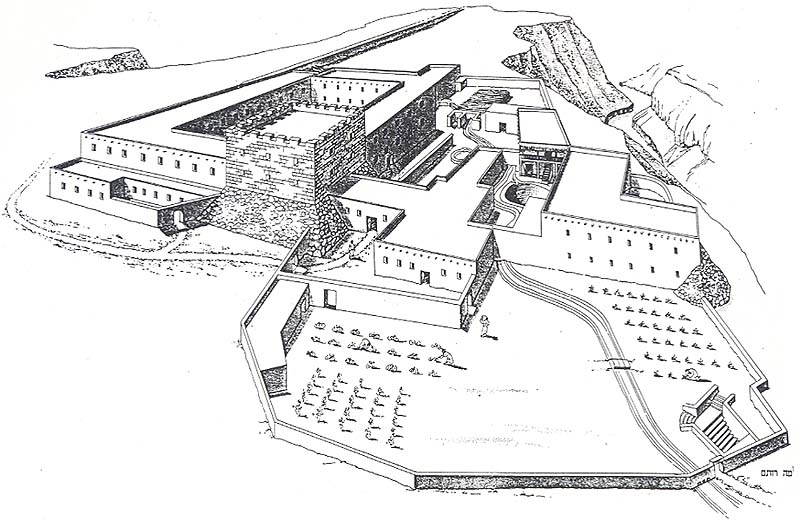

Hirschfeld: There are several points that weigh against Qumran being a military fortress. It is true the tower is well fortified, but the tower is not the only factor. Other elements must be understood as civilian aspects. For example, Qumran had many entrances. In military fortresses, there is always only one main entrance. We know many military fortresses from the late Roman period [third to fifth century C.E.]. In fortresses there is always a huge courtyard to provide space for the military unit. We don’t have this at Qumran. We have dwellings and other features, such as industrial workshops associated with agricultural functions. It is not logical to suggest that Qumran was built as a military fortress.

Magness: One of the many problems with Golb’s theory of a military fortress is that he never draws any comparisons to other fortresses. He identifies Qumran as a fort, or a fortress, but he doesn’t bring any parallels. He doesn’t say it’s like this or that site, so that you could go and check. You don’t know what he has in mind.

Secondly, he doesn’t talk about the population of the site. If it was a fortress, then who were the soldiers at the site? Were they Roman? Why? Were they Jewish? How could they be Jewish? These are among the many problems with his theory. If he could back up some of what he is saying, if he could bring forward some meaningful parallels and some solid information on who he thinks it was that occupied this site, then there might be a basis for more discussion.

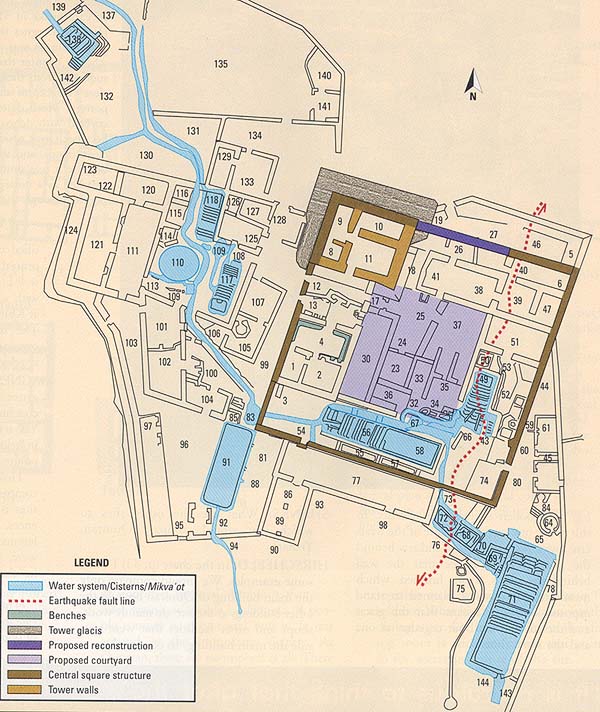

Shanks: Let’s look at a plan (“What Do You See?”) of the site from de Vaux’s excavation. [Roland de Vaux excavated Qumran from 1951 to 1956.]

Magness: There is a square structure in the center.

Eshel: In 1993, during Operation Scroll, [Israel Antiquities Authority director Amir] Drori told me that they found a wall going along [the eastern side, where de Vaux’s plan fails to show a wall], making the whole thing into a square. De Vaux didn’t record this wall. If this wall does exist, then what de Vaux called the centre bâtiment is a square. And we can find the additions that were added on the east and on the south.

Hirschfeld: I found an architectural seam, a straight seam that de Vaux did not mention, between the northeast corner of the main building and the northern wing (the proposed reconstruction on the plan). It very clearly demonstrates that there were at least two different phases of construction: the square building, which was probably the first stage of construction at Qumran, and additional wings all around it.

Shanks: Would you all agree that the square structure was the first stage of construction at Qumran?

Eshel: I’m not sure. I think that Qumran is divided into two buildings, the east building and the west building. The west building was some kind of administrative center. That is where the coin hoards and storage jars were found. The square building, on the other hand, was a kind of community center.

Shanks: Do you all agree with that?

Hirschfeld: No. I don’t agree at all. I understand it completely differently. I see a well-planned square building with a fortified tower in the northwest corner, and a small courtyard, which perhaps was larger in the beginning but over the generations became smaller.

Shanks: By the addition of the internal walls?

Hirschfeld: Right. This central building had a huge tower. I compare the tower with other towers at agricultural estates that rise up to four or five stories. Then I see additions on the west and southeast in a later phase. I don’t know exactly when. And I see an addition on the south [the so-called refectory and pantry]. In other words, I see two phases. The first one is the square building, and in the second we see the additions, including inside walls in the courtyard.

Magness: When were those additions made?

Hirschfeld: Probably during the Herodian period, which was when Qumran flourished.

Magness: But the pantry was destroyed in the earthquake of 31 B.C.E. That means this part of the structure had to exist before 31 B.C.E.

Hirschfeld: I think that the whole theory about the damage from the earthquake in 31 B.C.E. is wrong. There probably was an earthquake, although we know about it only from [the first-century C.E. historian] Josephus. I would guess the damage from this earthquake was repaired rather quickly and we don’t know what those repairs were. The famous crack that we have along the eastern part of the complex occurred after the site was destroyed by the Romans, that is, after 68 C.E. I don’t see any archaeological evidence of damage from the earthquake of 31 B.C.E.

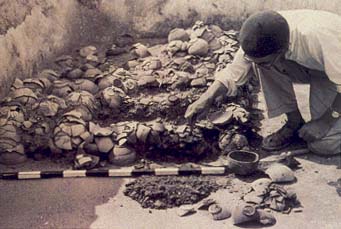

Magness: Yizhar [Hirschfeld], you can’t find clearer archaeological evidence for an earthquake than what you see at Qumran. This kind of fault line, which runs not just through the cistern but through part of the site as well, is totally consistent with an earthquake, as is the way the dishes in the pantry fell onto the floor. The dishes were stacked on shelves around the sides of the room. When the earthquake came, they all went boom—and fell. You can see later deposits on top of them. After the earthquake, they simply buried the destruction. It was left untouched after the earthquake. There is later material covering it. I don’t understand why you disassociate the earthquake when you have Josephus’s testimony. You have the dishes, which are consistent with the date at the end of the Hellenistic period. You are on the Afro-Syrian Rift, where you know there is earthquake activity all the time. It all makes perfect sense.

Hirschfeld: It seems to me ridiculous to think that after the earthquake of 31 B.C.E., the inhabitants of Qumran, who were flourishing, would live at the site with some parts of it destroyed. Especially in the main part of the central building! It simply doesn’t make sense.

Magness: I don’t know why you say that. Only the cistern [number 49 on de Vaux’s plan] that was too badly cracked went out of use. So did the pantry [number 86 on the plan] with the pottery that was simply covered over. They strengthened the tower at that point, and they cleaned up the parts that were repairable and continued to live there.

Shanks: According to de Vaux, the glacis at the base of the tower was added after the earthquake of 31 B.C.E. The earthquake supposedly destabilized the tower, and it needed a glacis or rampart to stabilize and strengthen it. Now I understand that you, Yizhar, question whether the glacis was added later or was part of the original tower structure.

Hirschfeld: Yes. After de Vaux’s excavation, someone made a probe when affixing the wooden staircase for tourists. In this probe one can see the face of the western tower wall previously hidden behind the glacis. One can see that the wall behind the glacis is not finished, which means that it was not planned to stand exposed, and that means that the glacis and the tower were built together at one and the same time.

Magness: How do you know? None of the stones at Qumran is finished, except for the stones around the doorways. All of the construction at Qumran is rubble, except for the areas around the doorways, which are ashlars [squared worked stones].

Hirschfeld: The tower wall behind the glacis looks like a foundation wall. It is very rough and not straight. All the exposed walls in Qumran are straight. This one is not.

Magness: It’s hard to discuss without seeing it.

Shanks: What are the other sites to which you would compare Qumran, Yizhar?

Hirschfeld: In the chart (“Home Sweet Home?”) I show some examples. We should compare only the main building of Qumran because the other buildings at the site are mainly workshops and other facilities that were outside the main building. In country houses throughout the Roman Empire, there is usually a clear separation between the dwelling unit and the workshops or industrial area for agricultural production.

We should compare the part in brown on the plan of Qumran (“What Do You See?”), which is the central square structure, with the plans of the other sites. None is exactly like the other. This is not like in churches, where one can put one church above the other and get an identical pattern. What we have are early Roman structures in Judea which have the same components, including a fortified tower and living quarters around a central courtyard. It’s a combination of a well-built courtyard house, sometimes with a [columned] peristyle courtyard [as at Khirbet el-Muraq] and a fortified tower. The tower provides protection for the owner of the estate. I believe that this model is relevant for Qumran.

Magness: I don’t think that any of us disagrees that there is a similarity between the core building at Qumran and the estates that Yizhar has pointed to. Yossi [Patrich] is right in acknowledging that Yizhar has correctly pointed out these similarities. They are valid.

However, what is important in the comparison between Qumran and these other sites is not the similarities but the differences. And there are very significant differences. Whoever the people of Qumran were, they naturally expressed themselves in the architectural vocabulary of their time, regardless of their religious beliefs.

There are significant differences that indicate that Qumran didn’t have the same kind of population as these other estates. Some of the differences have already been mentioned. The mikva’ot, for example. The interior decoration also differs. Many of the other sites have frescos, stucco, mosaic floors—features that are absent at Qumran. Some also have a Roman-style bathhouse with a hypocaust,d and you cannot ignore the pottery and the small finds. Qumran is significantly different from the other sites in this regard as well.

Eshel: At Qumran, we have only local pottery. In all the rest of those sites we have fine ware, like terra sigillata.e

Shanks: The publication of the Qumran final report has been assigned to Robert Donceel, who has enlisted his wife, Pauline Donceel-Voûte. The Donceels claim that there is fine ware at Qumran.

Magness: I saw the pottery from Qumran. I went through it all. Incidentally, in a discussion after a lecture I gave in 1992, at a New York conference, Pauline Donceel-Voûte admitted that there was very little fine ware at Qumran.5 She also did something that was very misleading. In her lecture at that same conference, she showed a slide that looked like a pile of sherds of fine ware. She simply took every single fragment of fine ware from Qumran and piled it up, and that was the slide. But if you compare the percentage of fine ware from Qumran with the percentage of fine ware from these other sites, there is a striking difference. There is virtually no fine ware at Qumran, and there are no imports at all. Even at Khirbet Mazin, the Dead Sea port just a little south of Qumran, imported amphorae were found there. Qumran doesn’t have a single one. At Jericho, just to the north, there is lots of imported material. It wasn’t that fine ware wasn’t accessible in the area. If people wanted it, they could buy it. It was around in the immediate vicinity. At Qumran, there are no imports at all. There is very little in the way of local fine ware—no terra sigillata, no Jerusalem painted bowls, no painted Nabatean pottery. I believe all the Qumran pottery was made at the site, but that has to be tested with neutron activation analysis.

Patrich: We are not balanced, because three of us claim that Qumran is a sectarian [religious] site, and Yizhar [Hirschfeld] believes it served another function.

I want to add another peculiarity at Qumran—the large halls. There are several large halls [numbers 77, 111, and 121 on de Vaux’s plan]. These halls are not warehouses. What were they for?

Another factor is the large hall that served as a dining room [number 77], especially with such a quantity of tableware located nearby. It is larger than for a family. Was it for workers? Did workers usually eat together at a common meal? Was it for soldiers? What kind of population was this dining room for? In my opinion, this dining room is another feature that points to the sectarian nature of the site.

Eshel: Another feature is the large cemetery at Qumran, which is not found in the rest of the sites.

Showing the similarities between Qumran and the other sites, which Yizhar has done, is important. We know where these people got their architectural ideas. There is no question that there are similarities—the tower, the square building. And I am glad that Yizhar has pointed this out, but I don’t think that these similarities prove what Qumran was used for.

Hirschfeld: Qumran is unique because de Vaux excavated the whole site, not just part of it. He was able to do this probably because of the availability of cheap Bedouin labor nearby. It is also unique because of its excellent state of preservation. Most of the other sites are not in the desert, so much less is preserved. And none of them was excavated to the extent that Qumran was. Also, Jodi [Magness] exaggerated a bit; I myself saw stucco at Qumran. There are remains of stucco in the tower as well as at other places. The Donceels mention it, and also some of the fine wares, including oil lamps, ceramic vessels and glass ware.6

Magness: I never said no fine wares at all.f

Hirschfeld: Also, there are remains of fine stone wares—a huge stone goblet about 80 centimeters [over 2 feet] tall. Also the column drums, capitals and bases found in the site by de Vaux. You can see them today at the site. They lend a kind of richness of decoration.

As far as the halls are concerned, there are halls in other sites too, for example, at Horvat Salit, at Khirbet el-Muraq, at Ramat Handiv, etc.

I agree that the so-called refectory hall of de Vaux was probably for dining because of the tableware. But why not think of it as a dining room for the workers? [Michael] Rostovtzeff refers to a Hellenistic estate at Fayum, in Egypt, where the manager of the estate and his assistants, servants and slaves all ate together in a dining room like the one in Qumran.7 It was quite common. Why not think about this possibility?

In a discussion, [Israeli archaeologist] David Amit mentioned the possibility that the large mikveh was for Jewish pilgrims on their way up to the Jerusalem Temple.8 That is how he interprets some other large mikva’ot he found in the Hebron hills. We may interpret the large mikveh at Qumran in the same way.

The cemetery at Qumran was preserved because of the desert climate. Presumably, similar cemeteries may have existed at other sites and were not preserved or have not yet been found. All in all, Qumran is not exceptional. All the discoveries at Qumran, including the ratio between the fine ware and the ordinary local ceramic vessels, are similar in all the other sites I mentioned.

Patrich: But you ignore many other features. Admittedly, the kernel for your speculation is there. But you cannot look just at the kernel and ignore all the other factors.

Shanks: What is he ignoring?

Magness: I can answer you on the pottery. I am going to repeat, there is very little fine ware compared to other sites in the immediate vicinity. Yizhar, I think you will agree that even at Ein Gedi, where you are excavating, you have a lot more fine ware.

Hirschfeld: No, no. Ninety-five percent of the material from Byzantine Ein Gedi is local.

Magness: Not the Byzantine period [324–638 C.E.]. The Byzantine period presents a totally different picture.

Shanks: I’d like to hear your analysis of locus 30 [on de Vaux’s plan], the so-called scriptorium, where scrolls were supposedly written. It is a hall. Did it have two stories?

Eshel: There were stairs leading to a second floor.

Magness: Clearly there were the remains of two floors.

Shanks: What was the function of that hall? Hanan?

Eshel: Well, everybody knows inkwells were found there.g

Hirschfeld: As far as I remember, de Vaux found two ceramic inkwells in the hall and one more made of bronze outside.

Eshel: [Solomon] Steckoll found a fourth in his small excavation in 1966 to 1967.9 Three or four inkwells at one site is unique, especially at a site the size of Qumran.

Magness: I have worked for many years on pottery reading at various archaeological sites, and I have never yet found an inkwell in any of the zillions of baskets of pottery that I have sorted.

Hirschfeld: A 1980 article on ancient inkwells reports on 15 of them from different places.10 It’s true that in the parallels I have cited, no inkwells were found, but these sites were only partially excavated. Inkwells were found in Jerusalem and also in the Galilee—in Meiron and en-Nabratein.11

Eshel: But we don’t have a room with more than one inkwell anywhere else right now. Even in the upper city of Jerusalem, in the rich buildings that [Nahman] Avigad excavated, he didn’t find such a room.h I don’t want to give the impression that I’m sure that room 30, or the second floor, was used as a scriptorium because I’m not sure.

The tables from that room are also unique. Once it was thought that those tables were used to write the scrolls. Then they decided that that was not convincing. Perhaps the tables were used to make the dry lines on the scrolls. They cannot be used as something that people lay on [as argued by the Donceels]; they’re too narrow.

Shanks: What about the possibility that the upper story was a fancy dining room, a triclinium, as the Donceels have argued?

Magness: You’d have to be a midget in order to be able to recline and dine on those benches because otherwise you’d fall off. They’re only 40 centimeters [about a foot] wide.

I’m not wedded to the scriptorium idea either. If somebody comes up with a better interpretation and says, “Look we have a nice parallel here that nobody ever looked at, and it’s not a scriptorium, it’s a ‘fill in the blank,’” that’s fine.

Shanks: But the so-called desk theory doesn’t hold up either.

Magness: You’re right! We just don’t know what they are.

Patrich: To reconstruct it exactly is difficult. There are things you cannot do. One of them is, you can’t recline. Perhaps you can lean against it or stretch a scroll along it.

Hirschfeld: To me it seems that the so-called tables are benches that were built along the wall, probably for sitting rather than reclining.

Eshel: Jodi [Magness] and I have just excavated a room in Yattir with a lot of benches. Benches are made of stone and then plastered. The tables from Qumran don’t have stone in the middle; they are built with plaster over reeds tied together. You can’t sit on this. Someone of my weight would break it.

Shanks: There’s only one fancy room at Qumran, or set of rooms. Room 4 [on de Vaux’s plan] has benches around it, and it has a pass-through to another room (room 2), and there’s a large stone installation like a stand on the other side of the pass-through. What is your interpretation of that? These rooms, it has been suggested, made up the Qumran library where the scrolls were studied.

Hirschfeld: I see locus 4 not as a place for sitting, but for storing. The benches are not for sitting—they are too narrow—but for storing jars, as in traditional Arab houses. The upper story, incidentally, was where the inhabitants lived. We often see this division of the lower and upper story in Roman and Byzantine country houses.

Shanks: Jodi, you shrugged your shoulders, as if to say “I don’t know what it’s for.”

Magness: Yes. Unless you have a room that has a really distinctive layout or very distinctive installations, the only way to determine what its use was, at least in its last phase of occupation, is on the basis of the artifacts found inside it. Until the material from Qumran is finally fully published, we won’t be able to answer a lot of the questions you’re asking. They’re up in the air. We can’t really know until we have the full publication of the material.

Eshel: We know Hartmut Stegemann’s suggestion that it [room 4] was a study room and that you had to show some kind of ID in order to enter this room and that the librarian was on the other side of the wall, and the scroll was ordered from him.12 I don’t want to play this game. Maybe he is correct; maybe he is not correct. I’m not sure that even if all the material found in Qumran is someday published, we’ll have an answer to this question.

Patrich: I agree with Yizhar [Hirschfeld] that we need to take into account the existence of a second story where people stayed and lived. The lower floor was for storage and light manufacturing.

Shanks: You’ve referred to the lack of a final report of de Vaux’s excavation. Do you think it will ever be published?

Eshel: After he died, I think the École Biblique made every possible mistake—they didn’t miss a single one.

They should have brought in someone who knows the local pottery, who is familiar with the archaeology of the area, who knows what’s happening in other sites. It was a mistake to bring in people [the Donceels] who were foreign to this. I once spoke with the Donceels about mikva’ot; they didn’t even know what the term meant. I had to explain it; and I had to explain who Ronny Reich is and the significance of his work. What happened is a pity. Then the Donceels published their interpretation, which is completely different from de Vaux’s.13 Then Jean-Baptiste Humbert published an article in Revue biblique that again creates new problems.14 I think it’s time that this material is published. We’re here debating, and we feel handicapped because we don’t have the material. We especially need the [pottery] sherds in order to determine when the site was established.

Shanks: Until now, de Vaux’s date of about 150 B.C.E. has been accepted as to when the site was established. More recently, I get the feeling from you archaeologists that you’re lowering the date so that it may be closer to 100 B.C.E.

Eshel: If all the material from Qumran is published, we will be able to answer this question. Right now it’s very hard. De Vaux published only complete vessels. This gives us only the three destruction layers. We need the sherds, especially rims.

Shanks: What were the three dates when the site was destroyed?

Eshel: In 31 B.C.E., around 9 to 8 B.C.E. and in 68 C.E. The earliest stratum we can confidently date is the stratum of the earthquake of 31 B.C.E. The question is, how far can we push back the establishment of the site? We’re handicapped because we don’t have the sherds.

Shanks: Jodi, I have the feeling that you were ready to come out and say that it wasn’t until 100 B.C.E. that Qumran was settled.

Magness: I think it may be even later. We’re not talking about the earlier, Iron Age [eighth to sixth century B.C.E.] settlement at Qumran. De Vaux dated the beginning of the sectarian settlement to 130 B.C.E. He was certainly influenced by the Dead Sea Scrolls and by his belief that Qumran was a sectarian settlement. In his Period 1a [the earliest sectarian settlement], he says he found only a few pieces of pottery, no coins and very little architecture. It looked to him like a very shortlived phase.

Period 1b ended with the earthquake of 31 B.C.E. On the basis of the presence of a large number of coins of Alexander Jannaeus [103–76 B.C.E.], he said Period 1b must have started no later than the time of Alexander Jannaeus.

If you place the beginning of Period 1b no later than the reign of Alexander Jannaeus and you think that Period 1a lasted a very short time, then you come out somehow around 130 for the beginning of Period 1a. That’s how he got his date.

The pottery of Period 1a is identical with the pottery of Period 1b, de Vaux himself admits. And he had a hard time identifying anything at all associated with Period 1a. I tend to think that his Period 1a doesn’t actually exist. I think we have no proof that the settlement at Qumran was established before 100 B.C.E. Exactly how much after 100 B.C.E. it was established is impossible to determine until we get some sherds that are associated with the establishment of the site.

The coins of Alexander Jannaeus remained in circulation for decades after the time of Alexander Jannaeus. [So Period 1b might have started later than de Vaux dated it.] Based on the large amount of material destroyed in the earthquake of 31 B.C.E., I think you have to say that the settlement existed for at least 20 years before the earthquake destruction, so you can say that it had to have existed by 50 B.C.E. How much earlier is an open question. I can’t say on the basis of what’s been published.

Shanks: Is de Vaux’s material going to be published, or is it lost?i

Magness: Rumors about de Vaux’s material fly all over the place; It’s here, it’s there, it’s lost. I don’t know where the material is. According to Jean-Baptiste Humbert [now in charge of the publication], the Donceels took some of it back to Belgium. I’ve seen a lot of Qumran pottery in the basement of the Rockefeller Museum. I saw some material in the École Biblique. We know that some of the coins got lost. Undoubtedly, some of the other material also got lost. But I’m sure that the records from de Vaux’s excavations still exist. There is a lot of unpublished pottery that still exists. I can tell you from having worked on the material from Yadin’s excavations at Masada, a lot of which got lost, that that did not hamper me from working on the publication because there were records of it. It needs to be gathered together and published.

Eshel: What is being planned at Qumran is also a mistake, that is, if the rumors are correct and Dr. Yitzchak Magen [district archaeologist for the area including Qumran] is going to dig the whole site.

Hirschfeld: But there is nothing left to dig.

Eshel: Yes, there is. Yitzchak Magen already started. Room 4, which we discussed, he excavated and found an Iron Age wall. I think this will happen more and more. If you go down below de Vaux’s excavation, you will find more and more Iron Age features. I think that Qumran deserves better. Qumran is an important site. Yitzchak Magen is a very good archaeologist, but he is working at a lot of sites. We need somebody who has spent a lot of time at Qumran, who appreciates its uniqueness and will study it in a way that will lead to a final publication.

Magness: I don’t think the site should be excavated any further until what has already been excavated is published.

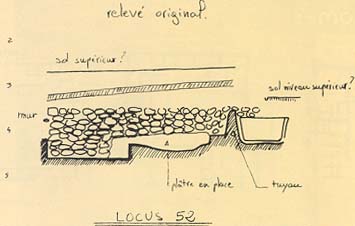

Hirschfeld: The material from Qumran must be published. What the Donceels have written is very sad. The situation is awful. It’s a disaster in every respect. Also because de Vaux dug in an unstratified way. He didn’t change locus numbers even when he dug through several floors—which means that there is no stratification at Qumran. He changed the locus number only when the debris layer was huge. And he did not publish section drawings. The only section drawing [of de Vaux’s] that we have was published by the Donceels [of locus 52, (see photo of section drawing)].15 In this section you can see that there are several floor levels, all with the same locus number. So the scientific value of the material from Qumran will relate only to the last period of occupation. I doubt that it will be very useful for earlier phases.

Magness: The fact that de Vaux didn’t change locus numbers doesn’t mean that there is no stratigraphy. There is stratigraphy at the site. You can read it in his notes. He describes the levels he is going through. There are photographs, and there are section drawings. They’re just not published yet. They are among the records that need to be published. The Donceels published one section drawing, but there are undoubtedly others. I’m not saying de Vaux’s records were perfect, but I think that we’ll be able to get a lot of information from them—if they’re ever published.

Shanks: Where did the people live at Qumran? I’ve heard a lot about there being no domestic quarters. How do you know that they didn’t live in this site? Or did they live in the site?

Patrich: In addition to the site, there are two types of caves nearby. In my opinion, some people did live at the site. And some of the caves also show signs of habitation. They are well cut. They are spacious enough. The finds in the caves—cooking pots, tableware, jars—indicate that they were occupied. Caves 7, 8 and 9, in my opinion, served one or two persons. Caves 4 and 10 served only one, in any case not more than two. In my opinion, that’s it for the marl terrace—at least on the basis of what has been published and what I could examine. As for the caves in the limestone cliffs, everyone who has studied them agrees that they are not habitable. If they show some traces of occupation, this is an occupation of a very ephemeral nature, perhaps of shepherds or refugees.

Shanks: What do you estimate the population at the site, apart from the caves?

Patrich: Not more than 50. If not 50, even less, much less. Perhaps 30 or 35. But this doesn’t exclude the possibility that this is a sectarian site.

Shanks: How do you account for 1,200 graves in cemeteries adjacent to the site?

Patrich: This does not contradict my estimate of the population that resided at the site. You know the famous [holy] site of Nabi Musaj—there are thousands of burials around there. It was a burial ground for Muslims. I doubt that more than 20 people permanently lived at the central building at Nabi Musa.

Qumran was a burial ground. What does it mean when ties with the Jerusalem Temple are severed by a whole religious community [as the scrolls seem to indicate]? Where would they be interred? What happens to sectarians whose festivals are observed on a different date from Jews in Jerusalem? [The sectarians described in the scrolls used a different calendar from Temple Jews.] Where will the sectarians go to celebrate? Such considerations enable us to understand how all kinds of installations, such as so many mikva’ot and such a large cemetery, can occur at the site whose permanent residents are not more than 30 or 50.

Shanks: You’re suggesting that the cemetery indicates that Qumran was a sectarian cemetery?

Patrich: Of course. It is an orderly cemetery with burial plots in rows. This is not something that occurred after a disaster or a war that killed more than a thousand people. The same for the mikva’ot. Qumran was a sectarian center in a remote place where people could have a contemplative experience.

Shanks: Hanan [Eshel], do you agree with what Yossi [Patrich] said?

Eshel: No. Yossi and Yizhar [Hirschfeld] have both worked on monasteries from the Byzantine period in the Judean desert. Those monasteries are different from Qumran. They are built on cliffs; monks affiliated with them lived in caves. I really think we have to disconnect Qumran from the Byzantine monasteries. They are different populations and different periods. I don’t see any reason to interpret Qumran by comparing them to monasteries. That is part of the reason why Yossi and I differ in our interpretation at some points.

I agree with Yossi that the caves in the marl terrace were inhabited. In Cave 8, they even found a mezuzahk at the entrance to the cave. These caves are man-made for the purpose of habitation. As someone who spends a lot of time at Qumran, even in the summer, I can testify that the only place where you feel relaxed is in Cave 4. When you take people down to Cave 4—even in the summer—the minute that you go there you feel that you can breathe.

I think that the important thing is the number of caves in the marl terrace. I think there were between 20 and 30 artificial caves at Qumran, and in every cave there were at least two people, in some, like Cave 4, as many as six. So I think between 100 and 200 people lived in Qumran.

Shanks: Are you assuming some caves have completely eroded away?

Eshel: Yes, I’m sure they did. The marl is very soft. De Vaux found a staircase leading from Cave 9 to the west, suggesting that it led to a “phantom cave.” I’m sure that in a decade Cave 4 will be destroyed. One rain in Qumran and Cave 4 will collapse. In addition, Magen Broshi and I excavated four additional caves that were inhabited.16

Shanks: How do you account for the 1,200 graves in the cemetery?

Eshel: One problem with the cemetery is that very few graves were excavated. De Vaux excavated only 36, Steckoll excavated another 9, 17 so the sample out of 1,100 graves is very small. Some of the excavated graves contained coffin nails, indicating that some of the people were brought to Qumran in coffins, probably brought from outside.

Shanks: What happened to the wood?

Eshel: The wood disappeared, even in Qumran.

Magness: It disintegrated.

Eshel: In addition, de Vaux found in one grave two people who were buried in a secondary burial. The bones were not arranged as in a skeleton. They were buried there after the flesh had decayed. This is clear proof that some people were brought from outside to the cemetery.

Shanks: There were very, very few secondary burials.

Eshel: Yes, but the total number of graves excavated is very small. I wish the cemetery could be excavated. I teach in a religious institution; I’m a religious Jew. I would never do it, but I would be very glad if somebody else did it—respectfully, burying the bones after they are studied.

Shanks: Yizhar [Hirschfeld] says that Qumran is not a sectarian site. The other three say it is. But there were many Jewish sects or groups at the time. Is there anything in the archaeology of the site that says that it’s the Essene sect?

Magness: No. People always ask me, “What do you think? Were they Essenes, or were they not Essenes?” I always avoid using the word “Essene.” My personal opinion is that they probably were some Essene group. I don’t know exactly how you define “Essene”; it’s very complex. But professionally I never use the word “Essene” because it’s not an archaeological problem and I am an archaeologist. I work with archaeological evidence. I don’t consider myself to be a Dead Sea Scroll expert or a text scholar or a Biblical scholar. The only way to determine whether they were Essenes is on the basis of the textual evidence—the scrolls and the historical sources—and that’s not my field of expertise.

Shanks: Do you connect the scrolls with the site?

Magness: Yes, absolutely. The pottery types from the [scroll] caves and the pottery types at the site prove the connection. Certain forms—the so-called scroll jars or a particular kind of oil lamp—are either unique to or characteristic of Qumran. These same forms were also found in the scroll caves.

Shanks: Yossi, you too have said Qumran is a sectarian site. Do you avoid identifying the sect as Essene?

Patrich: This is a difficult issue. The question has to do partially with archaeology but mainly with comparing what we know from literary sources about the Essenes—Josephus, Philo, Pliny—and what we know about the sect reflected in the scrolls. Altogether, there are many similarities, and I would say that the Dead Sea sect residing in Qumran was a kind of Essene group.

Shanks: Hanan, do you think that the sect was Essene?

Eshel: I always use the term “Qumran sect.” If you ask me if I believe that the Essenes were connected with the Qumran sect, I think they were. If you compare what Josephus wrote about Essenes with what appears in the scrolls, especially the Damascus Document and the Community Rule [also known as the Manual of Discipline],18 you will see that most of the things Josephus mentions appear in the scrolls. The problem is that some things seem to be different. Do you want to speak about 75 percent of the glass being full or 25 percent being empty? I will give only one example: Josephus tells us that joining the Essenes was a three-year process.19 The Community Rule says it’s a two-year process.20 But Josephus himself says there are two kinds of Essenes.21 In teaching my students, I try to show them that Qumran was probably one group within a broader movement of Essenes. So it’s not one to one; it’s not that the Qumran sect is the Essenes. The Qumran sect is one group of the Essenes. That’s the most I can do.

Shanks: Was Qumran an isolated site?

Eshel: It was. At that time the Dead Sea reached the cliffs. If you wanted to travel south along the Dead Sea, you had to take a boat. Qumran was on a dead-end route. Only people who wanted to reach Qumran would go that route.

Shanks: Do you agree with that, Jodi?

Magness: At the time that Qumran was inhabited, in the first century B.C.E. through the first century C.E., it was a very isolated settlement.

Shanks: Do you agree with that, Yizhar?

Hirschfeld: Not at all. It was a busy place on a main thoroughfare from Jerusalem and Jericho to Ein Gedi and to other settlements of Jews around the Dead Sea. Qumran was a crossroad. It’s easy to prove that Hanan and Jodi are wrong because there are several sites from the late Second Temple period showing that the water level was only a little bit higher than it is today. These settlements are along the patrol road of the army today. This road, right down to Ein Gedi, was open and not covered by the sea. Qumran was a busy place.

Shanks: Yossi?

Patrich: I would say that Qumran was remote, but not isolated.

Shanks: That’s an appropriate note to end on. Thank you all very much.

MLA Citation

Footnotes

The Hasmonean dynasty was created in the second century B.C.E., when the house of Mattathias the Maccabee began a struggle, ultimately successful, to establish a Jewish state in Palestine.

See Jodi Magness, “What Was Qumran? Not a Country Villa,” BAR 22:06.

See Hershel Shanks, “The Qumran Settlement—Monastary, Villa or Fortress?” BAR 19:03.

A hypocaust is an ancient central heating system consisting of a space under the floor supported by small columns for the circulation of warm air.

A high-quality pottery of the Roman period, terra sigillata is distinctive for its shiny red slip.

In the first century C.E., locally produced fine ware is very common at sites around Judea, such as Jerusalem, Jericho and Masada. Imported fine ware from the western Mediterranean, however, is relatively rare. There was no imported and very little local fine ware found at Qumran.

See Stephen Goranson, “Qumran: A Hub of Scribal Activity?” BAR 20:05.

See Nahman Avigad, “Jerusalem Flourishing—A Craft Center for Stone, Pottery and Glass,” BAR 09:06.

De Vaux did publish preliminary reports of his excavations in Revue biblique and in a volume that expanded on his lectures on the subject, Archaeology and the Dead Sea Scrolls (Oxford: Oxford Univ. Press, 1973). One volume containing photographs and a summary of his notes has been published recently by the École Biblique. See Jean-Baptiste Humbert and Alain Chambon, Fouilles de Khirbet Qumrân et de Aïn Feshkha, Novum Testamentum et Orbis Antiquus, Series Archaeologica 1 (Göttingen: Vandenhoeck and Ruprecht; Fribourg: Éditions Universitaires, 1994).

Nabi Musa is located south of the Jerusalem-Jericho road at the edge of the Jordan Valley. Muslim pilgrims stopped here to venerate Moses, whose tomb was traditionally thought to be visible across the Jordan Valley, on Mt. Nebo. Later, Nabi Musa itself came to be known as the site of Moses’ tomb.

Endnotes

Ronny Reich, “Mikva’ot (Jewish Immersion Baths) in Eretz-Israel in the Second Temple Period and the Mishnah and Talmud Periods” (Ph.D. diss., Hebrew University, 1990) (in Hebrew).

Günter Garbrecht and Yehuda Peleg, “The Water Supply of the Desert Fortresses in the Jordan Valley,” Biblical Archaeologist 57:3 (1994), pp. 161–170.

For an English translation, see Yoram Tsafrir, “The Desert Fortresses of Judea in the Second Temple Period,” The Jerusalem Cathedra 2 (1982), pp. 120–145.

For the published version of Pauline Donceel-Voûte’s report at the New York conference, see Robert Donceel and Pauline Donceel-Voûte, “Archaeology of Qumran,” in Michael O. Wise et al., eds., Methods of Investigation of the Dead Sea Scrolls and the Khirbet Qumran Site: Present Realities and Future Prospects, Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 722 (New York: New York Academy of Sciences, 1994), pp. 1–38; see also Jodi Magness, “The Community at Qumran in Light of Its Pottery,” in Wise et al., Methods; and Hershel Shanks, “Blood on the Floor at New York Dead Sea Scroll Conference,” BAR 19:02.

See Donceel and Donceel-Voûte, “Archaeology of Qumran,” pp. 5–14; see also Donceel, “Qumran,” in The Oxford Encyclopedia of Archaeology in the Near East, ed. Eric M. Meyers (New York and Oxford: Oxford Univ. Press, 1997), vol. 4, p. 395.

Michael Rostovtzeff, A Large Estate in Egypt in the Third Century B.C. (New York: Arno Press, 1979), p. 103.

David Amit, “Ritual Baths (Miqva’ot) From the Second Temple Period in the Hebron Mountains,” Judea and Samaria Research Studies 3 (1993), pp. 157–189 (in Hebrew).

A picture of this inkwell appears in Solomon H. Steckoll, “An Inkwell From Qumran,” Mada’ 13 (1969), pp. 260–261. See also Steckoll, “Investigations of the Inks Used in Writing the Dead Sea Scrolls,” Nature 220 (1968), pp. 91–98; and Y. Olenik, “Early Roman-Period Pottery Inkwells from Eretz-Yisrael,” Israel-People and Land 1 (1983–1984), pp. 55–66 (in Hebrew, with an English translation on pp. 10–11).

Eric M. Meyers, James F. Strange and Carol L. Meyers, “Preliminary Report on the 1980 Excavations at en-Nabratein, Israel,” Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research 244 (1981), p. 21.

See Hartmut Stegemann, Die Essener, Qumran, Johannes der taüfer und Jesus (Freiburg: Herder, 1993), pp. 53–85.

See Donceel and Donceel-Voûte, “Archaeology of Qumran”; Donceel-Voûte, “Les ruines de Qumrân réinterprétées,” Archaeologia 298 (1994), pp. 24–35, and “‘Coenaculum’—La salle á l’étage du locus 30 à Khirbet Qumran sur la mer Morte,” Banquets d’Orient, Res Orientales 4 (1992), pp. 61–84; and Donceel, “Repris des travaux de publication des fouilles au Khirbet Qumrân,” Revue biblique (1992), pp. 557–573.

Jean-Baptiste Humbert, “L’Espace Sacré à Qumrân: Propositions pour l’archéologie,” Revue biblique 101–102 (1994), p. 161.

Magen Broshi and Hanan Eshel, “How and Where Did the Qumranites Live?” in The Provo International Conference on the Dead Sea Scrolls: New Texts, Re-Formulated Issues, and Technological Innovations, ed. D.W. Parry and Eugene C. Ulrich (Leiden: Brill, 1997).

See Steckoll, “Preliminary Excavation Report in the Qumran Cemetery,” Revue de Qumran 6 (1968), pp. 323–344.

For a translation and an explanation of the role of the Manual of Discipline, see Geza Vermes, The Complete Dead Sea Scrolls in English (New York: Allen Lane/Penguin, 1997), pp. 26–48.