013

Five million Christian pilgrims travel each year to the grotto of Lourdes in southwestern France, where the Virgin Mary is said to have appeared to a peasant girl in 1858. The map of Rome is spotted with churches dedicated to the Queen of Heaven and Mother of God. The liturgical calendars of the Catholic and Orthodox churches devote more feast days to Mary than to any other saint.

Clearly, no woman has had more influence on Christian faith and practice than Mary, the mother of Jesus. Yet it would be extremely difficult to explain her tremendous role throughout history solely on the basis of what is said about her in the New Testament.

To learn how Mary came to fulfill this role, we must look outside the Bible. On the following pages, Ronald F. Hock of the University of Southern California explores the earliest Christian text to describe Mary’s life in detail—the Infancy Gospel of James. Although excluded from the Bible, this account has had enormous influence on later traditions.

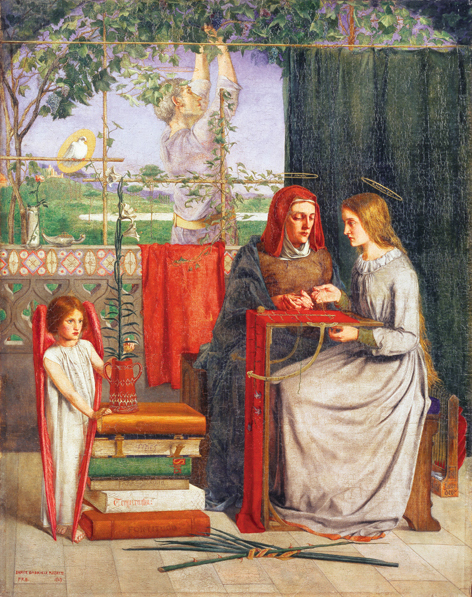

Few BR readers will have read the Infancy Gospel of James, but many of the stories and details—including the names of Mary’s parents, Anna and Joachim—will nevertheless seem strangely familiar, in part because artists from Giotto to Rossetti have been inspired by this apocryphal text. David R. Cartlidge, Beeson Professor Emeritus of Maryville College, selected the accompanying illustrations, which draw on the Infancy Gospel of James. In the photo captions, Cartlidge points out the apocryphal elements found in each. Finally, in the sidebar to this article, Vasiliki Limberis of Temple University explains how a bitter battle between a bishop and an empress led to the church’s official recognition of Mary as mother of God.—Ed.

014

Who were Mary’s parents? Where did she spend her childhood? Was it a happy one? How did she occupy herself as an adult? Why was she, above all other women, selected to be the mother of God? And what did Mary think about the extraordinary role she was called on to play?

A careful reading of the New Testament leaves us with more questions about Jesus’ mother than answers. For Mary is a relatively minor character in the Gospels—mentioned only a couple dozen times, often unnamed and usually silent. How did this unassuming figure come to be the most important woman in the Christian church?

As we shall see, it is in the early Christian texts known as the New Testament apocrypha that Mary is transformed into an important, fully developed character—one worthy of being called the mother of the Son of God.a This image of Mary would come to dominate later Christian piety.1

Although the New Testament says surprisingly little about Mary, it nevertheless reveals a subtle shift in focus on Mary from the earliest writings—the letters of Paul—until the time of Matthew and Luke. The earliest biblical reference to Mary appears in Paul’s letter to the Galatians, written in the mid-50s of the first century A.D.: “But when the fullness of time had come, God sent his Son, born of a woman, born under the law, in order to redeem those who were under the law, so that we might receive adoption as children” (Galatians 4:4).

This prosaic and passing reference to “a woman” indicates that interest in Mary had not yet taken root. Paul offers no suggestion of a miraculous birth. He is far more concerned with Jesus’ death and resurrection than his infancy.

Mary appears briefly but silently in the earliest New Testament gospel, the Gospel of Mark, written about 70 A.D. This gospel includes no birth account; it begins with Jesus as an adult. Mary is mentioned only twice—first when she and the family visit Capernaum after hearing that Jesus has lost his mind. The crowd informs Jesus, “Your mother and your brothers and sisters are outside, asking for you.” Scanning the crowd, Jesus responds: “Who are my mother and my brothers? Here are my mother and my brothers! Whoever does the will of God is my brother and sister and mother” (Mark 3:31–35). Later, when Jesus preaches in his hometown of Nazareth, a dubious crowd asks: “Where 016did this man get all this? What is this wisdom that has been given to him?…Is not this the carpenter, the son of Mary?” (Mark 6:1–3). For Mark, Mary represents Jesus’ humble origins.

The opening verse of Mark’s Gospel offers a different take on Jesus’ parentage, however: “The beginning of the good news of Jesus Christ, the Son of God” (Mark 1:1). By placing the title “Son of God” at the start of his narrative, Mark may well have prompted Christians to begin to ask a new question: Just how did Jesus come to be the Son of God?

By extending the gospel story back in time to the birth of Jesus to Mary, the Gospels of Matthew (written c. 80 A.D.) and Luke (c. 90 A.D.) begin to provide answers to this question. Mary remains on the scene a little longer in Matthew’s Gospel than she does in Mark’s, but here, too, she remains silent, and her role in our first account of Jesus’ birth is passive.b

The Gospel of Matthew relates:

Now the birth of Jesus the Messiah took place in this way. When his mother Mary had been engaged to Joseph, but before they lived together, she was found to be with child from the Holy Spirit. Her husband Joseph, being a righteous man and unwilling to expose her to public disgrace, planned to dismiss [divorce] her quietly. But just 017when he had resolved to do this, an angel of the Lord appeared to him in a dream and said, “Joseph, son of David, do not be afraid to take Mary as your wife, for the child conceived in her is from the Holy Spirit. She will bear a son, and you are to name him Jesus, for he will save his people from their sins”…When Joseph awoke from sleep, he did as the angel of the Lord commanded him; he took her as his wife, but had no marital relations with her until she had borne a son; and he named him Jesus.

Matthew 1:18–25

Soon after, wise men from the East arrive in Jerusalem, asking: “Where is the child who has been born king of the Jews? For we have observed his star at its rising, and have come to pay him homage” (Matthew 2:2). Terrified by this apparent threat to his throne, King Herod orders the massacre of all infants two years of age and younger. The king’s plans are foiled, however, when Joseph receives a warning from an angel in a dream. “Then Joseph got up, took the child and his mother by night, and went to Egypt, and remained there until the death of Herod” (Matthew 2:14–15).

Joseph, not Mary, plays the leading parental role in this birth account. He receives the angelic visitors; he directs all the family’s moves. Ever silent, Mary is clearly his subordinate.c

In Luke’s Gospel, however, Mary begins to think and act for herself. She even speaks:

In the sixth month the angel Gabriel was sent by God to a town in Galilee called Nazareth, to a virgin engaged to a man whose name was Joseph, of the house of David. The virgin’s name was Mary. And he came to her and said, “Greetings, favored one! The Lord is with you.”

But she was much perplexed by his words and pondered what sort of greeting this might be. The angel said to her, “Do not be afraid, Mary, for you have found favor with God. And now, you will conceive in your womb and bear a son, and you will name him Jesus…”

Mary said to the angel, “How can this be, since I am a virgin?”

The angel said to her, “The Holy Spirit will come upon you, and the power of the Most High will overshadow you; therefore the child to be born will be holy; he will be called Son of God…For nothing will be impossible with God.”

Then Mary said, “Here am I, the servant of the Lord; let it be with me according to your word.” Then the angel departed from her.

Luke 1:26–38

Luke offers our earliest explanation of why Mary was chosen to mother Jesus: She had “found favor with God.” Following the annunciation, Mary sets out to visit her elderly relative Elizabeth, then pregnant with John the Baptist, who immediately acknowledges that something extraordinary has happened to Mary. Elizabeth cries out, “Why has this happened to me, that the mother of my Lord comes to me?” (Luke 1:43).

After Mary returns home, the emperor Augustus calls for a worldwide census, and Joseph and Mary must travel to Bethlehem to be counted. Jesus is 018born en route: “And she gave birth to her firstborn son and wrapped him in bands of cloth, and laid him in a manger, because there was no place for them in the inn” (Luke 2:7). Following the birth, the family journeys to Jerusalem to make sacrifices.

The Gospel of John mentions Mary several times, although never by name. Instead, she is simply called “the mother of Jesus.” Although the Fourth Gospel includes no birth account, Mary appears briefly at the wedding in Cana (John 2:1–11), travels with Jesus to Capernaum (John 2:12) and is widely known as Jesus’ mother (John 6:42). Finally, she stands at the foot of the cross, where Jesus asks his beloved disciple to take care of her: “When Jesus saw his mother and the disciple whom he loved standing beside her, he said to his mother, ‘Woman, here is your son.’ Then he said to the disciple, ‘Here is your mother.’ And from that hour the disciple took her into his own home” (John 19:25–27).

Taken together, these gospel passages only begin to probe Jesus’ origins and parenthood. They suggest that Mary was favored by God, but they fail to reveal why. Only when we turn to the New Testament apocrypha do we find an explanation.

Written between the second and sixth centuries A.D., the Christian apocrypha include gospels, epistles, apocalypses and acts of various apostles that were excluded from the canon. A subgenre of apocryphal gospels known as “infancy gospels” focuses on Jesus’ earliest years. What may well be the earliest of the infancy gospels—the Infancy Gospel of James (Latin, Protevangelium Jacobi)—extends the gospel account back in time to include the birth and life of Mary up to the time Jesus is born.

Dating to the early second century A.D., the gospel claims (falsely, as we shall see) to be written by James, an apparent reference to the brother of Jesus (see Matthew 13:55; Mark 6:3; Galatians 1:19).d The gospel follows the standard format for Greek texts known as encomia, which ancient students of rhetoric (and apparently our gospel writer) once studied in their writing textbooks, called Progymnasmata. Encomia (singular encomium; from the Greek for “praise”) aim to demonstrate the praiseworthiness of their subjects. The Infancy Gospel of James attempts to prove that Mary is qualified to be the mother of God.

The first five chapters of the Infancy Gospel establish Mary’s nationality, homeland, ancestry and parentage—all typical opening topics of encomia. The story, the gospel’s opening verse relates, is based on “the records of the twelve tribes of Israel” (James 1:1).2

Mary’s tale begins with her parents, Joachim and Anna, a wealthy and prominent Jewish couple whose only plight is childlessness, for which they are scorned. When Joachim attempts to present a sacrifice at the Temple, he is rebuffed because he has not “produced an Israelite child” (James 1:5). Deeply troubled, Joachim banishes himself to the wilderness to pray. Anna is mocked by her maid Juthine, who insists that God has made the elderly woman sterile. Alone in her garden, Anna prays: “O God of my ancestors, bless me and hear my prayer, just as you blessed our mother Sarah and gave her a son” (James 2:9)—a reference to Sarah’s pregnancy with Isaac at age 90 (Genesis 17–21). Throughout these opening chapters, Anna is likened to some of the most praiseworthy of Old Testament women.

Anna and Joachim’s prayers are answered. They are informed separately by angels that Anna will bear a child. When the happy couple is reunited outside the city gate, Anna embraces Joachim, exclaiming: “Now I know that the Lord God has blessed me greatly” (James 4:9).

Anna vows to dedicate her child to God: “As the Lord God lives,” Anna promises, “whether I give birth to a boy or a girl, I’ll offer it as a gift to the Lord my God, and it will serve him its whole life” (James 4:2). Anna’s words echo those of yet another Old Testament mother, Hannah, who promises her son Samuel to the Temple (1 Samuel 2:11, 28). In nine months Anna gives birth to a girl, “and she offered her breast to the infant and gave her the name Mary” (James 5:9).

As is typical of encomia, the Infancy Gospel of James emphasizes the purity of Mary’s earliest years:

Day by day the infant grew stronger. When she was six months old, her mother put her on the ground to see if she could stand. She walked seven steps and went to her mother’s arms. Then her mother picked her up and said, “As the Lord my God lives, you will never walk on this ground again until I take you into the temple of the Lord.”

And so she turned her bedroom into a sanctuary and did not permit anything profane or unclean to pass the child’s lips. She sent for the undefiled daughters of the Hebrews, and they kept [Mary] amused.

James 6:1–5

When the precocious and pure little girl turns three, Joachim and Anna fulfill their vow to God by taking their daughter to the Temple in Jerusalem. The priests welcome Mary, who is loved not only by all the people but also, apparently, by heaven, for she is fed “like a dove, receiving her food from the hand of a heavenly messenger” (James 8:2).

At age twelve, about to become a woman, Mary poses a threat to the Temple’s purity. “What should we do with her so she won’t pollute the sanctuary of the Lord our God?” the priests ask God (James 8:4). An angel instructs the priests to summon all the widowers of Judea to the Temple. “[Mary] will become 021the wife of the one to whom the Lord God shows a sign” (James 8:8).

Hearing the news, Joseph—characterized here as a widower—“threw down his carpenter’s ax,” grabbed his staff and set out for the Temple. At the gathering, a dove flies out of Joseph’s staff and perches on his head. Not surprisingly, the high priest interprets this as a divine sign and gives Mary to Joseph. But the carpenter now has second thoughts: “I already have sons and I’m an old man; she’s only a young woman. I’m afraid I’ll become the butt of jokes among the people of Israel” (James 9:8). The priests warn Joseph about resisting the will of God, however, and Joseph prudently decides to accept Mary—but only as his ward, not his wife.

The Joseph of the Infancy Gospel is very different from the Joseph of the canonical accounts. There he is assumed to be of marriageable age and is in fact engaged to Mary (Matthew 1:18, 20, 24; Luke 1:27, 2:5) and eventually marries her (Matthew 1:24). Here, Joseph is an old man, embarrassed to be receiving a young woman from the Temple into his house. He never treats Mary as anything more than a person requiring his protection. When he brings her home, he immediately sets out to build houses, trusting that God will protect her. His absence, as well as his age, serves to quell any doubts about whether he might have been intimate with Mary.

Furthermore, in the canonical gospels, Jesus is simply Mary’s firstborn child; he has younger siblings born to Joseph and Mary (Matthew 13:55–56; Mark 6:3). But in the Infancy Gospel, Jesus is Mary’s only child; his brothers are Joseph’s children by an earlier marriage. Mary thus remains a virgin her whole life.

Having established the purity of Mary’s upbringing, the Infancy Gospel of James turns to the next topic typically found in encomia: adult pursuits, which, for a woman, include spinning and weaving. Thus, while Joseph is away, Mary, now age 16, keeps busy spinning purple and scarlet threads for a new Temple curtain. One day when Mary takes a break from her work and goes out to fill her water jar, she is hailed by a male voice: “Greetings, favored one! The Lord is with you. Blessed are you among women” (James 11:2). Terrified, Mary rushes home. As she resumes her spinning, an angel appears and announces that she will bear God’s son:

“Do not be afraid, Mary. You see, you have found favor in the sight of the Lord of all. You will conceive by means of his word.”

But as she listened, Mary was doubtful and said, “If I actually conceive by the Lord, the living God, will I also give birth the way women usually do?”

And the messenger of the Lord replied, “No, Mary, because the power of God will overshadow you. Therefore the child to be born will be called holy, a son of the Most High. And you will name him Jesus—the name means ‘he will save his people from their sins.’”

And Mary said, “Here I am, the Lord’s slave before him. I pray that all you have told me comes true.”

James 11:5–9

022

After this annunciation scene, the narrative follows rather closely, if more briefly, the Lukan version of Mary’s visit with Elizabeth (Luke 1:39–56). Unlike in the gospel, however, in the Infancy Gospel of James, Elizabeth is just the first of many characters who will acknowledge that something miraculous has happened to Mary.

The next ten chapters, the largest section of the Infancy Gospel, enumerate Mary’s virtuous deeds. Virtue—which is typically the most important topic of an encomium—is understood to refer to the four cardinal virtues: justice, self-control, wisdom and courage. Thus, when Mary is six months pregnant, Joseph returns home, angry at Mary for getting pregnant and angry at himself for not protecting her. He accuses her of having been seduced, but she courageously asserts that she has maintained self-control: “I am innocent. I haven’t had sex with any man” (James 13:8). Joseph decides to “divorce her quietly” (James 14:4),e until an angel appears to him in a dream: “Do not be afraid of this girl,” the angel soothes Joseph, “because the child in her is the Holy Spirit’s doing” (James 14:5). Henceforth, Joseph will protect Mary.

Mary is soon put on trial again. A visitor to their home notices that she is pregnant and informs the high priest. Summoned before the priest, Mary once again asserts her self-control: “As the Lord God lives, I stand innocent before him. Believe me, I’ve not had sex with any man” (James 15:13).

Incredulous, the high priest orders Joseph to return Mary to the Temple, but when Joseph bursts into tears, he allows them to prove their innocence by undergoing a “drink test,” in which Joseph and Mary are given water to drink and then sent out to the wilderness. If they return unharmed, this will be accepted as proof of their virtue.f Both pass the test, and the high priest publicly exonerates them: “If the Lord God has not exposed your sin, then neither do I condemn you” (James 16:7). Mary and Joseph return home “celebrating and praising the God of Israel” (James 16:8).

023

At this point, the Infancy Gospel of James begins to parallel the birth accounts in Matthew and Luke, but with many additions, omissions and changes from the canonical stories. According to the Infancy Gospel, Caesar Augustus has ordered that everyone in Judea (not the whole world, as Luke 2:1 has it) be enrolled in a census. As in the Gospel of Luke, Joseph heads for Bethlehem with Mary. But unlike in the canonical account, he is also accompanied by his sons from an earlier marriage and he is not sure how to register Mary: “I’ll enroll my sons, but what am I going to do with this girl? How will I enroll her? As my wife? I’m ashamed to do that. As my daughter? The people of Israel know she’s not my daughter” (James 17:2–3). But before Joseph can decide, Mary cries out for assistance: “Joseph, help me down from the donkey—the child inside me is about to be born” (James 17:10). Joseph guides Mary into a nearby cave for privacy, stations his sons outside to guard her and heads out in search of a midwife.

While Joseph is away, Jesus is born. At that moment, Joseph has a vision of time stopping: Rolling clouds pause, birds are suspended in midair, Joseph himself stops mid-stride; all of nature takes notice of the birth. The vision equates Jesus’ birth to his death, which is marked by darkness and earthquake.

The suspension is only temporary. Joseph soonfinds a midwife and they return to Mary. As they approach, a dark cloud withdraws from the cave; from inside emanates a light so intense “that their eyes could not bear to look” (James 19:15). “And a little later, that light receded until an infant became visible; he took the breast of his mother Mary” (James 19:16). The midwife, who would typically aid in the birth and nurse the child, has nothing to do. Her uselessness simply emphasizes Mary’s exceptional qualifications as a mother.

Recognizing that she has witnessed a miracle, the midwife pronounces the central confession of the gospel: “A virgin has given birth” (James 19:18). Outside the cave, the midwife relates this marvel to a woman named Salome, who remains dubious. “Unless I insert my finger and examine her,” Salome swears, “I will never believe that a virgin has given birth” (James 19:19). But Salome’s bold gynecological exam only causes her hand to burst into flame. She screams: “I’ll be damned because of my transgression and my disbelief; I have put the living God on trial. Look! My hand is disappearing! It’s being consumed by flames” 024(James 20:3–4). She is healed, however, when she reaches out to touch the infant Jesus. Salome, like Joseph and the high priest before her, is converted from doubt to belief.

After the birth of Jesus, Joseph plans to continue his journey to Bethlehem, but his trip (and the narrative) is interrupted by the arrival of the magi from the East. As in the Gospel of Matthew, the magi, after meeting with Herod, follow a star to Bethlehem, although here the star stops above the cave rather than the home of Matthew’s Gospel. At this point, however, the Matthean account is left behind. When Herod orders the massacre of the innocents, it is not Joseph who leads the family to safety. Indeed, Joseph is not mentioned again in the Infancy Gospel. Mary must save Jesus herself: “When Mary heard that the infants were being killed, she was frightened and took her child, wrapped him in strips of cloth, and put him in a feeding trough used by cattle” (James 22:3–4). Mary’s actions are borrowed from Luke 2:7, but here they appear in a completely different context, one that emphasizes Mary’s courage.

At this point, Mary and Jesus also disappear from the narrative, even though the gospel continues for more than two chapters. Many readers have been perplexed at their absence, but the encomium structure provides an explanation. In encomia, the narration of the subject’s virtuous deeds is followed by a comparison of the subject’s actions with the virtuous actions of others. Here, the text turns to Elizabeth and her husband, Zechariah, the parents of John the Baptist, who also respond with courage to the threat to their son posed by Herod. The Infancy Gospel underlines Mary’s bravery by placing the equally brave acts of Elizabeth and Zechariah immediately after hers.

The final chapter of the Infancy Gospel does not continue the narrative but provides information about the author, date and place of writing:

Now I, James, am the one who wrote this account at the time when an uproar arose in Jerusalem at the death of Herod. I took myself to the wilderness until the uproar in Jerusalem died down. There I praised the Lord God, who gave me the wisdom to write this account. Grace will be with all those who fear the Lord. Amen.

James 25:1–4

Since Herod died in 4 B.C., the Infancy Gospel of James purports to be a nearly contemporaneous account of the events it narrates—perhaps written by Jesus’ own brother. If true, this gospel would be the earliest Christian writing we have. Unfortunately, these claims do not stand up to scrutiny. For this Infancy Gospel is clearly dependent on Matthew and Luke, which were not written until 80 to 90 A.D.3 Since Jesus’ brother James died in 62 A.D.,4 he could not have been the author.

025

In the end, we are left with an anonymous narrative written sometime after the Gospels of Matthew and Luke. It would have taken some time for the canonical accounts to become known and authoritative—perhaps 25 or 30 years. It is possible that the gospel was written by the mid-second century and that the Christian apologist Justin Martyr borrowed from it the detail of Jesus’ birth in a cave (Dialogue 78.5). This suggests a date between 125 and 140 A.D.

Consequently, the Infancy Gospel can be placed on a trajectory whose starting point is the opening verse of Mark, which described Jesus as the Son of God and turned Christians’ attention to the beginning of Jesus’ life. By the third century, Christian writers were making more frequent references to the Infancy Gospel. Origen (c. 185–254), for example, refers to the brothers of Jesus as sons of Joseph by a previous marriage. Clement of Alexandria (c. 150–212) speaks of the midwife who attended Mary and proclaimed her to be a virgin.5

It was not until 431 A.D., when Mary was officially recognized as the mother of God (in Greek, the Theotokos) at the Council of Ephesus, that the Infancy Gospel of James began to exert tremendous influence on Christian art and piety (see the sidebar to this article).6 As Christians throughout the empire began to honor Mary, the account of Mary’s life in the Infancy Gospel became the basis of festivals in her honor, such as those celebrating her birth on September 8 and her presentation in the Temple on November 21. During both festivals portions of the Infancy Gospel were read liturgically. In addition, many churches were dedicated to Mary, and the painters and mosaicists hired to decorate them turned to the Infancy Gospel of James for appropriate subjects. The Infancy Gospel of James came to shape the dominant image of Mary.

At the beginning of the Infancy Gospel, an angel promises Mary’s mother Anna: “Your child will be talked about all over the world” (James 4:1). The promise is fulfilled. The detailed and praiseworthy biography in the Infancy Gospel of James has prepared Mary for her central role in Christian faith and piety.

Five million Christian pilgrims travel each year to the grotto of Lourdes in southwestern France, where the Virgin Mary is said to have appeared to a peasant girl in 1858. The map of Rome is spotted with churches dedicated to the Queen of Heaven and Mother of God. The liturgical calendars of the Catholic and Orthodox churches devote more feast days to Mary than to any other saint. Clearly, no woman has had more influence on Christian faith and practice than Mary, the mother of Jesus. Yet it would be extremely difficult to explain her tremendous role throughout history […]

You have already read your free article for this month. Please join the BAS Library or become an All Access member of BAS to gain full access to this article and so much more.

Already a library member? Log in here.

Institution user? Log in with your IP address or Username

Footnotes

On these early Christian texts, see David R. Cartlidge, “The Christian Apocrypha: Preserved in Art,” BR 13:03.

For more on the conflicting gospel accounts of Jesus’ birth, see “Where Was Jesus Born?”—a debate between Steve Mason and Jerome Murphy-O’Connor in BR 16:01.

To be sure, Mary’s designation as a virgin, parthenos (Matthew 1:23, citing Isaiah 7:14; Luke 1:27), contributed to her characterization. But see J. Edward Barrett, “Can Scholars Take the Virgin Birth Seriously?” BR 04:05; and James E. Crouch, “How Early Christians Viewed the Birth of Jesus,” BR 07:05.

For more on Jesus’ family, see Richard J. Bauckham, “All in the Family,” BR 16:02.

Joseph’s decision is inappropriate in the context of the Infancy Gospel, where Mary is Joseph’s ward and not his wife. Apparently, the author borrowed the phrase from Matthew 1:19 without taking into consideration the changed circumstances of his own narrative.

Endnotes

For further reading on Mary, see Beverly Roberts Gaventa, Mary: Glimpses of the Mother of Jesus (Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 1999); and Jaroslav Pelikan, Mary Through the Centuries (New Haven: Yale Univ. Press, 1996).

Citations follow Ronald F. Hock, The Infancy Gospels of James and Thomas, The Scholars Bible 2 (Sonoma, CA: Polebridge Press, 1995).

That the Gospel of James depends on Matthew and Luke, and not the other way around, is easily demonstrated. For example, Joseph’s decision to dismiss or divorce Mary quietly (James 14:4) recalls a nearly identical remark in Matthew’s account (Matthew 1:19), but in James it makes little sense since marriage is never contemplated. It does fit the situation in Matthew, however, suggesting that Matthew is the source.

Furthermore, this gospel answers a question that only arises when both the Matthean and Lukan birth accounts are known. Matthew contains Herod’s murder of the infants (Matthew 2:16–18), but does not mention the birth of John. Luke mentions both the births of Jesus and John (Luke 1:57, 2:7), but does not include the murder of the infants. But reading both canonical gospels, a question arises: How did John escape Herod’s soldiers? The Infancy Gospel of James answers this question, revealing that the author knew of the two canonical birth stories.