When visitors to Jerusalem are shown a large cave called “Gethsemane” on the lower slopes of the Mount of Olives, they usually give a perfunctory look and hurry on to the famous Garden of Gethsemane, the small garden of olive trees adjacent to the Church of All Nations. Here pilgrims can sit and reflect on the momentous events of Jesus’ arrest in what seems a more appropriate, if less authentic, environment.

Most of these pilgrims are never told that the New Testament does not mention a “Garden of Gethsemane.” The Cave of Gethsemane, on the other hand, is very probably a genuine Biblical site—the location of Jesus’ arrest—unlike so many of the “traditional” holy sites of Christianity that have little or no claim to authenticity.

The cave, within a property now owned by the Franciscan Custody of the Holy Land, certainly looks unimpressive. Enclosed in a flat-roofed, semicircular building, the cave is reached by a long corridor to the right of the courtyard leading to the traditional Tomb of the Virgin. Its placement makes it seem an afterthought, though in fact it was a Christian holy site long before anyone thought to place the Tomb of the Virgin Mary beside it. The interior of the rather spartan cave has traces of two levels of Byzantine (fourth–sixth-century) mosaics, intriguing medieval ceiling and wall decorations, and modern altars on a modern stone floor. These features, however, do not seem too inspiring to most visitors and testify only to the fact that the cave has been modified many times over the course of its long history.

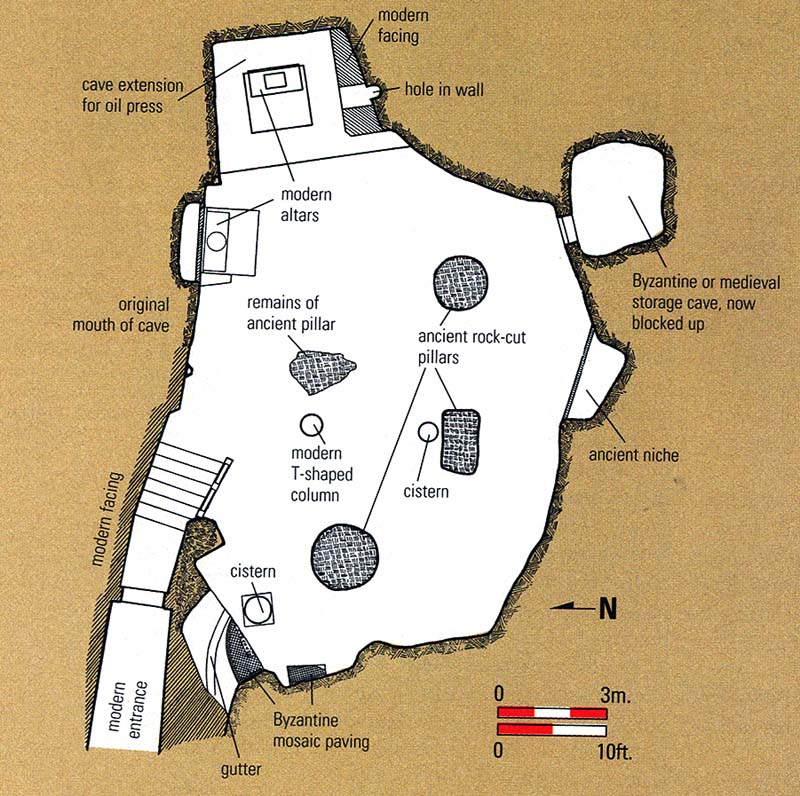

In the first century, the cave was not tucked behind a large building, as it is today. Excavations conducted by the Franciscans in 1956–1957 revealed that the natural mouth of the cave, lying to the north, was over 16 feet wide. The cave itself had been much extended long before the Byzantine period and has been used for agricultural purposes.

The earliest gospel, Mark, describes Jesus and his disciples going out to the Mount of Olives after the Last Supper (Mark 14:26) and specifically identifies their stopping place: “They went to a place called Gethsemane” (Mark 14:32). Mark does not call it a garden but simply a “place” or “property,” in Greek ch

Mark implies that, at the moment of betrayal, Jesus is not simply with Peter, James and John but with all the disciples who came with him across the Kidron Valley to Gethsemane. The armed crowd, carrying swords and clubs, seizes Jesus. One of the disciples standing near Jesus draws his sword and cuts off the ear of a servant of the high priest. A young man in the gathering, who seems to have been asleep in nothing more than a linen cloth or undergarment, a sind

Luke and Matthew, basing their accounts of the arrest on Mark, have similar stories. Luke mentions that Jesus spent his nights “on the Mount of Olives” (Luke 21:37) during the time he was in Jerusalem, but at first does not say exactly where. Matthew also refers to him sitting and teaching his disciples somewhere at a place on the Mount of Olives (Matthew 24:3). As in Mark, both Luke and Matthew refer to Jesus and his disciples going to the Mount of Olives after the Last Supper (Matthew 26:30; Luke 22:39). According to Matthew, Jesus goes with them to “a place named Gethsemane” (Matthew 26:36), but there is no mention of a garden. Luke never bothers to record the name of the place, but simply indicates it was where Jesus regularly slept: “He came out and went, as was his custom, to the Mount of Olives; and the disciples followed him. When he reached the place, he said to them, ‘Pray that you may not come into the time of trial’” (Luke 22:39–40). Luke’s account does not single out Peter, James and John. Jesus goes away from all his disciples “about a stone’s throw” and prays. He returns only once, to find them all fast asleep, and asks them to get up and pray. Judas arrives, and the scene is the same as in Mark, apart from a few details: for example, Jesus heals the ear of the high priest’s servant, the poor young man who lost his clothes is not mentioned and there is no direct reference to Jesus’ disciples all running away. Matthew’s story (Matthew 26:36–56) is very close to that of Mark, almost word for word, apart from a few minor changes and the subtraction of the tale of the naked man. Clearly both Luke and Matthew thought this detail anecdotal and irrelevant.1

Neither Mark, Matthew nor Luke speak of a garden. Gethsemane is simply a “place” or “property” on the Mount of Olives.

The Gospel of John, however, mentions something called a k

John’s account goes like this: “After Jesus had spoken these words, he went out [from Jerusalem] with his disciples across the Kidron Valley to where there was a garden/cultivated area (k

In John, Jesus and his disciples enter “into” (eis) the cultivated area, which implies that some kind of wall surrounded it. There was at least a clearly demarcated outside and inside. No details are given about the nature of the cultivation. That was not crucial to the story. Perhaps it was a small market garden. There is nothing said in any of the gospel accounts about the existence of a cave. Again, this was not necessary for the story.

Some very good reasons lead us to believe, however, that a cave was located in this walled, cultivated area, and that Jesus and his disciples slept in this cave rather than out in the open.

Looking closely at the text of John’s gospel, we see that Jesus “went out” (ex

The Greek word Gethsemane comes from an Aramaic or Hebrew term that most likely means “oil-press.” The word gat on its own in Aramaic and Hebrew frequently means “wine-press.” But its meaning is actually broader. In rabbinic literature, gat refers to a place for the preparation of oil.3 The broadest meaning of the word would encompass any pit or cave used for a particular purpose.4 The Hebrew word shemanim, a plural form, is used for different kinds of oil,5 gifts of oil6 and oil stores.7 So we can assume the Hebrew name of the place was Gat-shemanim, literally “press of oils.” Since different grades of olive oil were made, the plural form may reflect the various distinctions or types.

The possible name of the cave in Aramaic, Gat-shemanin, presumably sounded very much like Greek Geths

Archaeological evidence tends to support this cave as the site of Gethsemane. Excavations indicate that the present Gethsemane cave was indeed once used for olive-oil pressing.8

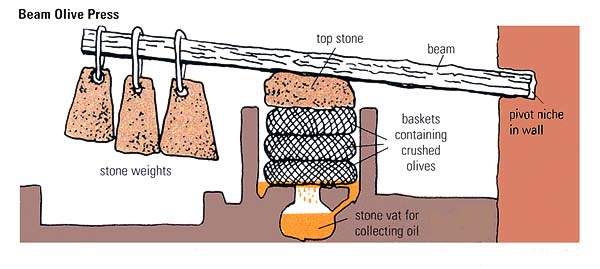

The interior of the Gethsemane cave has greatly changed over the centuries, and only vestiges of its original use remain (see the sidebar “A Welcome Refuge: Inside the Cave of Gethsemane”). The present floor is about 40 inches above the level of the original floor. The cave is extremely large, measuring approximately 36 by 60 feet (11 by 18 meters). The cave roof was supported by four rock-cut pillars, three of which still exist. As noted above, the remains of the wide original entrance can be seen on the north side. An oil-press probably stood in a roughly square artificial cave extension in the eastern wall. The evidence for this is a hole cut into the south wall of this recess. A hole may not seem much proof, but it was most likely cut to hold the wooden horizontal bar of the press.9 This beam held weights that would ensure heavy pressure on the olives, so that the oil would be squeezed out. It is hard to imagine any other reason why someone would cut a hole in the wall here. We can be sure that the press was for olives and not for grapes, because wine-presses are never found underground. Caves were often used for oil-presses, however, because their warmth helped the process.10

The recent discovery of a number of olive-oil installations at ancient Maresha (Tell Sandahanna) provides useful information about olive-presses in the centuries just before the time of Jesus. So does an olive-pressing installation in Jerusalem, not yet published.11

The presses were located in caves. A beam was secured at one end between two rock-cut ledges in a deep recess in the cave wall, as was, no doubt, the beam of the Gethsemane press. Three stone weights were usually hung by a rope on the wooden beam. At Maresha, these stones weighed between 300 and 1,100 pounds.12 A pit, into which the weights slowly descended, was cut in the floor. The mashed olives, stacked in baskets, were piled in a deep circular shaft between the rock ledges; the oil was collected in a vat below.

In eleven of the underground olive-pressing installations at Maresha, the presses were accompanied by circular crushing basins, almost 6.5 feet wide, with lens-shaped crushing stones. There are no remains of a crushing basin or stone in the Gethsemane cave today. In the ninth century, a monk named Bernard recorded that he saw four “round” or “curved” tables where Jesus and the apostles had supper.13 This would fit well with the remnants of a circular crushing basin.

There is some reason to believe that the Gethsemane cave held not one, but two olive-presses. The evidence for this appears in pilgrim accounts, dating from the sixth century to the Middle Ages, which testify to the existence of four rock ledges in the cave. Each recess for an olive-press requires two rock ledges to support the press’s beam. If the pilgrims saw four, then there may have been two presses. None of the pilgrims, however, suggests that the ledges have anything to do with olive pressing. Early in the sixth century, a pilgrim named Theodosius wrote that he saw four “couches” for the 12 apostles; he notes that “each couch holds three people.”14 The two ledges cut into recesses for the olive baskets and collecting vat in the presses at Maresha measure about 40 inches wide by 40 inches high and are therefore wide enough for three (slim) people to sit on, side by side. It seems quite possible that what Theodosius really saw were the remains of two recesses for olive-presses, with two ledges per recess.15

One of these ledges appears to have disintegrated by the end of the sixth century; an anonymous pilgrim from Piacenza, in about 570, mentions only three “couches.”16 Pilgrims wishing to take home mementos may have chipped the ledge away, or the rock may have simply fallen apart.17 The pressure of the heavy beam on the oil baskets created lateral pressure on the rock into which the ledges were cut. Also, pilgrims would climb on these ledges to gain a spiritual reward. The Piacenza Pilgrim writes that he and his party reclined on the “couches” to gain their blessing. In time, if the rock was not strong, these ledges would have cracked.

The curved tables noted by Bernard in the ninth century also may have been the remnants of the ledges, which had a concave arc cut out of them to fit around the baskets of olive pulp. With wear and tear and the edges chipped away, the ledges would have come to look much like facing semicircles. That only three ledges remained seems clear from a 12th-century pilgrimage account by Saewulf, who describes the three “beds” where the disciples Peter, James and John fell asleep.18 Some time between the Middle Ages and today, these rocky ledges and the remains of the crushing basin were completely chipped away.

A pilgrim named Arculf reported to the abbot Adomnan of Iona (c. 680) that he saw a cistern “in the floor of the cave … [and] it has a huge shaft sunk deep, which goes down straight.” The remains of this cistern have been discovered below an ancient hole in the cave ceiling, which was to let in air, light and (periodically) rainwater. Adomnan tells us in fact that there were two cisterns, one cut into the floor, and another that “goes down to an untold depth below the mountain.”19

That there were two cisterns in the ancient olive-pressing works is not surprising. Water was useful for cleaning the olives and the equipment, as well as for washing hands.

All this evidence leads to the conclusion that this cave was clearly used for olive pressing and had a crushing basin near its mouth, as well as two cisterns.

Even for an olive-oil-press, the cave would have been unusually large and impressive. As possibly the largest olive-oil processing site on the Mount of Olives, it would have been well known.

The spacious cave would have been a useful storage area as well. Oil-presses were only used in the autumn and winter,20 after the olive harvest; by spring, when the festival of Passover took place, caves that held olive-presses were used only for storage. Therefore, when Jesus and his disciples were in Jerusalem for Passover, the cave would not have been used for oil pressing. However, it would have been an excellent place to spend the night: warm, dry and roomy, with a cistern inside for water. The owner of the property may have been sensible enough to rent it out as accommodation. At festival times, thousands of people came to Jerusalem,21 and every lodging in the city and surrounding villages was taken. Any kind of shelter would have been considered as a lodging place. This cave was close to Jerusalem and probably securely located in a pleasant, cultivated enclosure.

It is extremely improbable that Jesus and his disciples would have spent the night out in the open sleeping amid olive trees. As anyone knows who has camped in the Judean hills in spring, the nights are cold and the dew is heavy. One simply cannot camp out without shelter at this time of year without becoming extremely cold and damp. The Gospel of John explicitly states that Jesus was arrested on a chilly night: Peter stands warming himself by the fire in the courtyard of the high priest “because it was cold” (John 18:18). The story of the young man who was dressed only in a sind

That Jesus was arrested in or just outside a cave also fits well with what we read in the gospel stories. We cannot know exactly what took place in every detail because the Gospels differ, but the basic story remains constant. It seems fairly clear that Jesus crossed over the Kidron Valley (in this part known as the Valley of Jehoshaphat) with a group of disciples and went a little way up the Mount of Olives to a cultivated enclosure. The group went inside, as they often did. They had been camping there for several days prior to the Passover festival. They either rented the property, or else the owner had offered it to them out of respect for Jesus. We can imagine them entering the warm cave, lighting little lamps and taking off their coats to sleep on as they prepared for bed. Perhaps Jesus was restless, and called Peter, James and John over to him, asking them to stay alert. He went forward from the cave entrance, still within the cultivated enclosure but alone, praying in the darkness. In the close coziness of the cave, and with heads befuddled with wine, Peter, James and John fell asleep with everyone else. Jesus returned to find them all blissfully unaware of what was about to happen. Then Judas arrived with a group sent by the Roman and chief priestly authorities of Jerusalem to arrest Jesus. Jesus came out of the cave entrance and was greeted by Judas. The disciples awoke and realized what was happening. A scuffle broke out. Some disciples tried to defend Jesus; then, realizing it was hopeless, and perhaps admonished by Jesus, they rapidly escaped. One young man lost his clothes in a struggle with a guard and then fled. Everyone ran away, and they were allowed to do so, for the authorities wanted only Jesus. They tied him up and marched him out to Jerusalem, leaving the cave of Gat-shemanin, and the enclosed garden around it, empty.

Three hundred years later, Christians began to visit this cave to recall the arrest of Jesus, which they believed had taken place there. It was one of the earliest sites to be venerated by Christian pilgrims. Because the name of the place probably remained the same over the centuries, people had little difficulty in identifying it. The people of Jerusalem still spoke a dialect of Aramaic, now known as Syriac. The Jerusalem church may have kept alive the memory of the site of Jesus’ betrayal. But, like the gospel writers before them, none of the earliest pilgrims mentions that Gethsemane was a cave, even though they are quite specific about its location.

The nun Egeria, for example, who made a famous tour of the Holy Land in about 382, describes the path followed by pilgrims on Good Friday. They go “into Gethsemane,” where they are provided with candles “so that they can all see.”22 Clearly, they are going into some place that is darker than outside; but Egeria does not bother to note that it was a cave.

Only in the early sixth-century account by Theodosius do we find explicit mention of Gethsemane as a large cave.23 He writes: “This place is in a cave, and now two hundred monks go down there.” But even after this date writers failed to note this feature.24 Gethsemane was Gethsemane; somehow everyone knew it was a cave.

It was not until the 12th century that anyone thought of a Garden of Gethsemane, located adjacent to the cave. But the cave was never entirely abandoned even when Christian imagination, aided by the depictions of European art, sited the arrest in an olive grove. Western pilgrims began to associate the site with the place of Jesus’ anxious prayer, called “the Agony.” Eventually, even this identification became little known, but the cave remained a peculiar stop on the pilgrim trail—and remains so to this day—one that people often go into and out of without a second thought, presuming it to be nothing much, a mere invention. However, of all the traditional Christian holy sites in and around Jerusalem, the Cave of Gethsemane is one of the most likely to be authentic.

Since archaeology shows that the cave held an olive-oil-press, and the Gospels refer to a place known as Gethsemane, which most likely meant “oil-press,” we are justified in considering the cave and Gethsemane to be one and the same. The cave is located just across the Kidron Valley, precisely where the Gospels suggest that Gethsemane was located. There is no other competing cave in the vicinity. Furthermore, Jesus and his disciples most likely did not lie down under the stars, but took shelter here during the cool spring nights. The evidence suggests that the cave of Gethsemane was the place they used as sleeping quarters, and here—or just outside—Judas caught them unawares.

MLA Citation

Endnotes

For the authenticity of the story of the naked man, see J. M. Ross, “The Young Man Who Fled Naked, Mark 14:51–2, ” Irish Biblical Studies 13/3 (1991), pp. 170–174. The beginning of the story differs slightly in Matthew and Mark. Matthew adds that Jesus stated directly that he wanted to “go away” to pray. Therefore, when it is written that he “took to himself” (paralab

For this observation, see Albert Storme, Gethsemane (Jerusalem: Franciscan Printing Press, 1972), p. 24.

See Virgilio Corbo, Ricerche archeologiche al Monte degli Ulivi, Gerusalemme (Jerusalem: Franciscan Printing Press, 1965), pp. 1–57; Louis-Hugues Vincent and Felix-M. Abel, Jérusalem: recherches de topographie, d’archéologie et d’histoire. ii. Jérusalem nouvelle (Paris: Gabalda, 1914), p. 335, fig. 147. See also, John Wilkinson, Jerusalem as Jesus Knew It (London: Thames and Hudson, 1978), pp. 127–131.

For olive-presses in general, see Gustaf Dalman, Arbeit und Sitte in Palästina, vol. 4 (Gütersloh, 1935), pp. 153–290. M. Heltzer and D. Eitam, eds., Olive Oil in Antiquity: Papers of the Conference Held in Haifa (Haifa: Univ. of Haifa, 1987).

Dalman, Arbeit und Sitte, p. 322. There are many examples of underground oil-presses from the region of Beth Guvrin. See Y. Teper, “The Oil Presses at Maresha Region,” in Olive Oil in Antiquity, pp. 25–46, and Amos Kloner and Nahum Sagiv, “The Technology of Oil Production in the Hellenistic Period: Studies in the Crushing Process at Maresha,” in Olive Oil in Antiquity, pp. 133–138.

I am indebted to Dr. Amos Kloner for this observation. I am also grateful to Dr. Kloner for taking me to visit some of these caves when I was annual scholar at the British School of Archaeology in 1986.

For further details, see Amos Kloner and Nahum Sagiv, “The Olive Presses of Hellenistic Maresha, Israel,” in Bulletin de Correspondence Hellénique Supplement XXVI, pp. 119–135.

In my book, Christians and the Holy Places: The Myth of Jewish-Christian Origins (Oxford: Clarendon, 1993), p. 200, I suggested that these “ledges” may have been the remaining uprights of screw operated presses. I am indebted to Dr. Kloner for pointing out that such screw presses only appeared at the end of the Roman period and were not in use at the time of Jesus.

In the Maresha cave, stone slabs, cut with concave arcs to fit snugly, were placed over the tops of ledges that had been cracked by extensive use. See Kloner and Sagiv, “Olive Presses,” pp. 127–128.

Saewulf, Relatio de peregrinatione 17; compare Theoderic, Liber de Locis Sanctis 24, Second Guide 124.