The Genesis of Judaism

042

Judaism has long been characterized by adherence to the laws of the Torah. Comprising manifold prohibitions and positive commandments, these laws have come to regulate all aspects of Jewish life. The scope of Torah law is so broad as to give the impression that no sphere of human experience is left unregulated. It covers daily prayers and rituals, weekly Sabbaths and annual festivals, dietary laws, life-cycle events, conjugal life and family law, criminal and civil laws, agriculture, ritual purity, and (in antiquity) rites pertaining to the Jerusalem Temple.

When did the Jewish people begin to keep these regulations? At what point in time did Jewish society first come to recognize the laws of the Torah as authoritative, and when did its members first begin to put these rules into practice in their daily lives? When, how, and why did all this come about?1

The natural place to begin our inquiry is with the Hebrew Bible. It is in the Pentateuch (also known as the Torah or the Five Books of Moses), after all, that we find God instructing Moses with the litany of dos and don’ts that form the basis of the Torah. But already as Moses descends from Mt. Sinai, we see the people of Israel breaking the most fundamental of these rules by worshiping a golden calf. The situation hardly improves after that. Much of the rest of the biblical narrative is a chronicle of Israel’s disregard for divine admonitions and of the grim consequences this neglect brought to the nation and its land.

A survey of all the books of the Hebrew Bible outside the Pentateuch reveals something rather astonishing: Ancient Israelite society is never portrayed as keeping the laws of the Torah. The Israelites during the time of the First Temple are never said to refrain from eating pork or shrimp, from doing this or that on the Sabbath, or from 044wearing mixtures of linen and wool. No one is ever said to blow a shofar on Rosh Hashanah, to fast on Yom Kippur, or to refrain from eating or possessing leavened bread on Passover. Nor is anybody ever said to wear fringes on their clothing, to don tefillin on their arm and head, or to have an inscribed mezuzah on the doorposts of their homes. Whatever it is that the biblical Israelites are doing, they do not seem to be practicing Judaism!

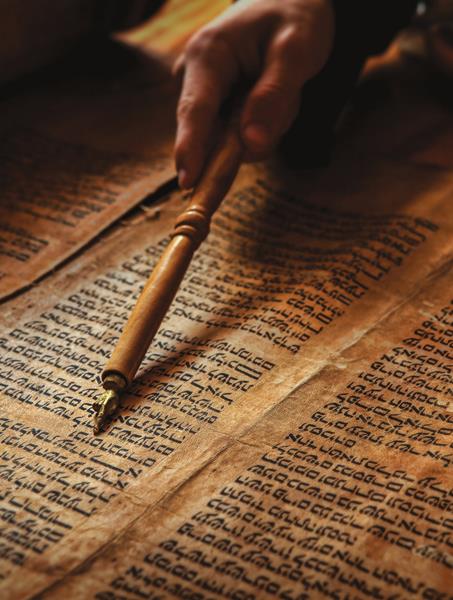

In an attempt to solve the problem of Judaism’s beginnings, modern biblical scholars look to the biblical figure of Ezra as the primary catalyst for the promulgation of the Torah among the populace of ancient Judea. According to the biblical account (Ezra 7:1-26), Ezra was a priestly scribe sent on a mission from Babylon to Jerusalem by Artaxerxes, king of Persia, with a royal injunction to enforce the Mosaic Torah upon the people of Yehud (the name of the Persian province of Judea). After his arrival, Ezra gathers a mass assembly in a central square of Jerusalem where, standing on a wooden platform, he reads aloud from a Torah scroll and teaches the divine laws in detail (Nehemiah 8).

For 19th-century scholars, these stories suggested that the Torah came to be regarded as authoritative law during the Persian period (539–332 B.C.E.), probably around the middle of the fifth century, when Ezra’s mission is thought to have taken place. This has been the reigning paradigm within which scholars of early Judaism tend to date the widespread promulgation of the Torah and the beginnings of Judaism itself.

I see two major problems with this model. First, the biblical narrative itself describes Ezra’s success as strikingly ephemeral. A short time after Ezra’s public reading from the Torah, the people of Yehud are said to be breaking the laws of the Torah by desecrating the Sabbath and marrying foreign women (Nehemiah 13:15-30). Second, we must consider what kind of historical information can be derived from the Ezra accounts. The biblical narratives provide extremely valuable historical evidence about the beliefs and ideologies of the biblical writers. These texts offer primary evidence for the history of ideas. The evidence they provide about what the masses of ordinary people were actually doing, on the other hand, is only indirect and thus very difficult to assess. These texts are clearly not the best source of information about social history. Because of both of these problems, I find little reason to surmise from the Ezra narratives that the Persian period marks the first emergence of a Judean society characterized by widespread adherence to the Torah.

When did ancient Judeans, as a society, first begin to observe the laws of the Torah in their daily lives? When did ordinary people—the farmers, craftspeople, and homemakers—first begin to regard the Torah as normatively binding and put into actual practice its detailed rules and regulations?

To answer these critical questions about Judaism’s origins, I believe we must begin by 045exploring the first century C.E., an era for which we possess a great deal of textual and archaeological evidence for widespread observance of the laws of the Torah. From there, we will proceed backward in time, until we have reached a point when we can no longer see such evidence. This will establish the latest possible time when widespread observance of the Torah likely first emerged.

Strict observance of the dietary laws—especially abstinence from pork—is noted time and again by first-century C.E. writers such as Philo of Alexandria, the authors of the New Testament, Josephus, and even several non-Judean authors writing in Greek and Latin. Many of these writers also tell of widespread observance of the ritual purity laws outlined in Leviticus, a practice confirmed by the archaeological remains of hundreds of ritual immersion pools, along with the ubiquitous chalk vessels, which were regarded as impervious to ritual impurity.a

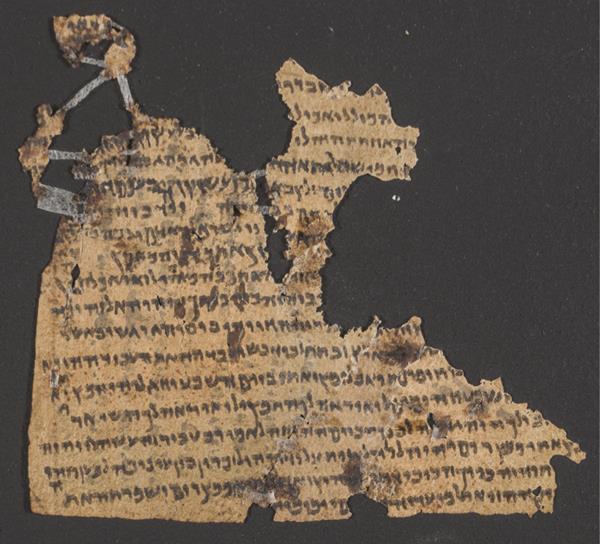

During this time, Judeans strictly eschewed depictions of humans or animals in their art and architecture, apparently in strict compliance with the second commandment (Exodus 20:4; Deuteronomy 5:8). Dozens of tefillin (phylacteries) and several possible mezuzot—all inscribed with passages from Exodus and Deuteronomy—have been found in caves near Qumran and elsewhere in the Judean Desert. First-century writers, Judean and non-Judean alike, attest to the widespread observance of the Sabbath and of such festivals as Passover, Yom Kippur, and Sukkot. The four species of Sukkot are even depicted on bronze coins minted in the fourth year of the Great Revolt (69/70 C.E.). This evidence reveals beyond any doubt that the laws of the Torah were widely regarded as binding within first-century Judean society.

Proceeding backward in time, we continue to find in the first and second centuries B.C.E. some evidence for the wide-spread observance of Torah laws. Several letters and decrees promulgated by Roman officials in the mid-first century B.C.E. directed cities around the Mediterranean to allow local Judean communities the freedom 046to observe their Sabbath laws (Josephus, Antiquities 14.226 ff; 16.163, 168). Around 70 B.C.E., a quip about Judean avoidance of pork is attributed to the Roman orator Cicero (Plutarch, Life of Cicero 7:6). Immersion pools and chalk vessels begin to appear archaeologically around the end of the second century B.C.E. The earliest surviving tefillin, found at Qumran, may also date to the late second or the first century B.C.E.

From their earliest Judean mintages around 130 B.C.E., Hasmonean coins completely avoided figural images. Most strikingly, many of these coins feature on their obverse a floral wreath framing a lengthy legend of dense text that covers almost every available space. These legends provide the name and title of the Hasmonean ruler and also cite “the assembly of the Judeans.” It seems clear that the designers of these coins were attempting to display a virtual portrait of the Hasmonean leader while avoiding any graphic image. The underlying message was clear: The highest echelons of the political leadership had endorsed the Torah’s strict ban on images.

Our trail of evidence for observance of the Torah’s laws ends around the middle of the second century B.C.E. As we proceed further back in time, we no longer find any evidence—textual or archaeological—to suggest that the laws of the Torah were widely observed within Judean society. No texts from before the mid-second century speak of Judeans avoiding pork or other 047prohibited species of meat or seafood.b No archaeological or textual evidence from before the mid-second century suggests that Judeans were adhering to the complex web of Pentateuchal ritual purity laws. The same lack of evidence applies to the avoidance of figural art and the observance of the Sabbath prohibitions, the Yom Kippur fast, and the tefillin and mezuzah rituals. Not only do we possess no evidence that these practices and prohibitions were widely observed—we lack evidence that the laws of the Torah on these matters were widely known at all!

It is possible that positive evidence for all these practices prior to the mid-second century B.C.E. simply may not have survived. However, certain evidence that has survived from earlier periods suggests that Judeans were not observant of the Torah laws. Remains of catfish found in several Persian-period archaeological contexts in Jerusalem indicate that Judeans ate this species of scaleless fish that was prohibited by the Torah.2 Images of humans and animals appear on every coin minted in Judea in the fourth and early third centuries, some of which also display the names of Judean leaders, such as “Yehizqiyah the 048governor” and “Yohanan the priest.” Fifth-century papyri and ostraca from a Judean community on Elephantine, Egypt, together with clay tablets from contemporary communities of Judeans in Babylonia, suggest that Judeans sometimes paid reverence to deities other than the Judean God YHWH and that they did not even know of a seven-day week, not to mention any prohibitions against conducting transactions on the Sabbath.3

Given the available evidence, I believe that the Hellenistic period (332–63 B.C.E.) was the epoch that most likely witnessed the earliest emergence of Judaism. Specifically, I believe that the Torah was probably made the “law of the land” during either the third or second century B.C.E.

Throughout the third century, Judea was under the control of the Ptolemies, a Macedonian dynasty founded by Ptolemy I, who had served under Alexander the Great and seized Egypt following the death of the famed Hellenistic conqueror in 323 B.C.E. Ptolemy’s son and successor, Ptolemy II Philadelphus (r. 284–246 B.C.E.), 049is known to have instituted significant legal reforms around the year 275 B.C.E. Separate courts were established for different ethnic groups, with certain courts set up to hear cases of Greek-speaking parties and others for native Egyptians—each according to their own laws. The Judeans living under Ptolemaic rule would also have required a set of laws under which they were to be governed. It may have been precisely these reforms that played a significant role in re-characterizing the Pentateuch as the normatively binding, prescriptive law of the Judeans.4 If this is correct, we may speculate that Judaism itself might have been born out of the Ptolemaic court reforms of the early third century.

Another intriguing possibility is that the Torah was adopted as law more than a century later, when Judeans enjoyed a brief period of self-governance following the Judean revolt that broke out under the leadership of the priestly family of the Hasmoneans, probably around 167 B.C.E. Over the course of the next 25 years, the Hasmonean brothers Judas Maccabeus, Jonathan Apphus, and Simon Thassi slowly consolidated their control over Judea, until a fully independent Judean polity was established under the rule of Simon Thassi in 142 B.C.E.

Recently, some scholars have suggested that it was the Hasmonean family that sponsored the Torah as an instrument for the unification of their newly autonomous state.5 I would also offer that the early Hasmonean leaders may have decided to solidify their position vis-à-vis both their subjects and their enemies by officially ratifying a document that might serve to codify the core narratives of the nation’s origins together with the officially sanctioned Judean laws. This single, composite work would have served the Hasmoneans in a way roughly akin to an amalgamated American Declaration of Independence and the Constitution of the United States. The Pentateuch—with both its stories about Israel’s origins and its laws—would have served such a role magnificently. In adopting the Pentateuch as the formal conceptual and legal foundation of the newly emergent Judean state, the Hasmonean rulers would have provided a rallying point around which the people of Judea might unite. With this, Judaism itself would have been born.

From its earliest origins, Judaism emerged and developed in manifold directions. Rabbinic Judaism was one pathway by which Judaism continued to thrive and expand, but other, parallel and no-less-influential byways emerged. In fact, both Christianity and Islam are well rooted in the Judaism whose origins we have explored here. Viewed in this way, the emergence of Judaism was the catalyst for setting the course of much of world history over the past 2,000 years.

Throughout much of history, Jewish life and culture have been characterized by strict adherence to the practices and prohibitions given in the Torah. The origins of that observance, however, have remained a mystery. Consider the archaeological discoveries and ancient texts that reveal when and why ordinary Judeans first adopted the Torah as their authoritative law.

You have already read your free article for this month. Please join the BAS Library or become an All Access member of BAS to gain full access to this article and so much more.

Already a library member? Log in here.

Institution user? Log in with your IP address or Username

Footnotes

1. See Yonatan Adler, “Watertight and Rock Solid,” BAR, Spring 2021.

2. For the problem of linking the material absence of pigs with a Torah prohibition, see Lidar Sapir-Hen, “Pigs as an Ethnic Marker? You Are What You Eat,” BAR, November/December 2016.

Endnotes

1.

These are the central questions addressed in my recent book, The Origins of Judaism: An Archaeological-Historical Reappraisal (New Haven: Yale Univ. Press, 2022).

2.

Yonatan Adler and Omri Lernau, “The Pentateuchal Dietary Proscription against Finless and Scaleless Aquatic Species in Light of Ancient Fish Remains,” Tel Aviv 48 (2021), pp. 5–26.

3.

Ilaria Bultrighini and Sacha Stern, “The Seven-Day Week in the Roman Empire,” in Sacha Stern, ed., Calendars in the Making (Leiden: Brill, 2021), pp. 10–79, esp. 11–17.

4.

Michael LeFebvre, Collections, Codes, and Torah: The Re-characterization of Israel’s Written Law (New York: T&T Clark, 2006), pp. 146–182.

5.

Reinhard G. Kratz, Historical and Biblical Israel: The History, Tradition, and Archives of Israel and Judah, translated by Paul M. Kurtz (Oxford: Oxford Univ. Press, 2015), pp. 185–186; John J. Collins, The Invention of Judaism: Torah and Jewish Identity from Deuteronomy to Paul (Oakland: University of California Press, 2017), pp. 184–185.