New testament scholars, both Jewish and Christian, have for years accepted the existence of a group of gentiles known as God-fearers. They were thought to be closely associated with the synagogue in the Book of Acts. Although they did not convert to Judaism, they were an integral part of the synagogue and provided fertile ground for early Christian missionary activity. As pious gentiles, the God-fearers stood somewhere between Greco-Roman piety and Jewish piety in the synagogue.

In his classic but now somewhat outdated study titled Judaism in the First Centuries of the Christian Era, Harvard scholar George Foot Moore argued that the existence of the God-fearers provides evidence for the synagogue’s own missionary work outside of Palestine during the first century A.D. The God-fearers were the result of this Jewish missionary movement. Although Jews may not have been actually sending out missionaries to proselytize the heathen, the influence of Jewish outreach was nevertheless felt in a world hungry for something more than mere empty religious forms.

Recent scholarship adds authority to Moore’s conclusions. The critical Greek words are phoboumenos (plural: phoboumenoi), meaning “fearing one,” and sebomenos (plural: sebomenoi), meaning “worshipping one.”

In 1962, a standard German reference work drew a distinction between God-fearers, on the one hand, and proselytes or converts, on the other. The God-fearers, we are told, were more numerous. “They frequent the services of the synagogue, they are monotheists in the biblical sense, and they participate in some of the ceremonial requirements of the Law, but they have not moved to full conversion through circumcision. They are called … sebomenoi or phoboumenoi ton theon.”1

The Encyclopaedia Judaica, published in 1971, tells us that “in the Diaspora there was an increasing number, perhaps millions by the first century, of sebomenoi, gentiles who had not gone the whole route towards conversion.”2

Other scholars describe the God-fearers with equal confidence. For the late Israeli scholar Michael Avi-Yonah, these God-fearers were a “numerous class” of gentiles under the empire; “although most of them did not feel able to shoulder the whole burden of the Law, they sympathized with Judaism … They were to be found in the provinces as well as in Italy, even at Rome … As they often belonged to the upper classes, their mere presence added in the eyes of the authorities to the weight of Jewish influence … ”3

David Flusser, another distinguished Israeli scholar, wrote in 1976 that the existence of these “many God-fearers” reveals that “Hellenistic Judaism had almost succeeded in making Judaism a world religion in the literal sense of the words.”4 Martin Hengel, a prominent German scholar, agrees with Flusser as to the number and influence of the God-fearers, although Hengel draws different conclusions: “The large number of [God-fearers] standing between Judaism and paganism in the New Testament period … shows the indissoluble dilemma of the Jewish religion in ancient times. As it could not break free from its nationalistic roots among the people, it had to stoop to constant and ultimately untenable compromises” (1975).5 This comment by Hengel is doubly unfortunate, in that it moves from what may be a misinterpretation of Acts to what is surely an anti-Jewish statement. Hengel’s conclusion may derive from the theology of the Protestant Reformation and its understanding of Judaism.6 But, as we shall see, there is theology at work in Luke himself as he composes Acts; indeed, Acts is best described as “theological history,” a term applied to it by Robert Maddox, or even as “theology in narrative form.”7 As we will spell out at the end of this essay, we see the God-fearers as theological characters, an integral part of Luke’s understanding of the Church in its relation to pagans and Jews.

It is in the New Testament that we find the principal evidence for the God-fearers.8 Indeed, the best-known God-fearer is a Roman soldier who eventually became a Christian. His name was Cornelius; he was a centurion stationed in Caesarea. Cornelius, we are told in chapter 10 of the Acts of the Apostles, was a “devout man who feared God,” as did his household (Acts 10:2, Revised Standard Version). He prayed “constantly.” In a vision Cornelius is told to send to Joppa in Judea for Simon Peter. He does so; Simon Peter comes and tells him that “God shows no partiality … Everyone who believes in [Jesus] receives forgiveness of sins through his name.” The Holy Spirit had poured out—apparently for the first time—“even on the Gentiles” (Acts 10:45).

In the Jerusalem Bible, the critical part of Acts 10:2 states that Cornelius “and the whole of his household were devout and God-fearing.” A note tells us that “the expressions ‘fearing God’ (Acts 10:2, 22, 35; 13:16, 26) and ‘worshipping God’ (Acts 13:43, 50; 16:14; 17:4, 17; 18:7) are technical terms for admirers and followers of the Jewish nation who stop short of circumcision” (JB, 1966, NT 217).

As already mentioned, the important Greek words are phoboumenos and sebomenos. They are used several times in Acts, in chapter 10 and elsewhere. (In chapter 10, see verses 22 and 35.) In chapter 13, Paul addresses the Sabbath crowd at the synagogue in Antioch: “Men of Israel and you that fear God” (Acts 13:16). The phrase is sometimes translated as “fearers of God” or “God Fearers.” (See also verse 26.)

In chapter 17, we read that in Athens Paul “argued in the synagogue with the Jews and the devout persons” (Acts 17:17). (See also Acts 16:14; 17:4 and 18:7.)

Apart from these eleven references containing some form of phoboumenos (fearing one) and sebomenos (worshipping one), the New Testament is silent as to any alleged God-fearers.

In the traditional reconstruction, the God-fearers may be described as follows:

1. They are gentiles interested in Judaism, but not converts or proselytes; the men are not circumcised.

2. They are found in significant numbers in the synagogues of the Diaspora, from Asia Minor to Rome.

3. As a group, they are particularly significant for students of the New Testament and early Christianity because Christianity supposedly recruited from their ranks a great number of its earliest members.

While Acts provides the only New Testament support for the existence of the God-fearers, scholars have also found isolated and oblique references to them in classical literature, as well as in Greek and Latin inscriptions, although the technical terms phoboumenos and sebomenos appear only in Acts. The other scattered evidence for Diasporaa God-fearers in Greek and Latin literature and inscriptions is all held together by the references in Acts; the argument is that the various terms in the Greek and Latin literary texts and inscriptions are in fact being used in a technical sense, that is, as God-fearers. Additional evidence for the existence of God-fearers is also drawn from rabbinic discussions of sympathizers, proselytes and converts.

We strongly doubt that there ever was a large and broadly based group of gentiles known as God-fearers. The archaeological evidence first pointed us in the direction of this conclusion. This led us to reexamine the literary evidence, including Acts, and our reexamination simply confirmed our doubts. We’ve concluded that the God-fearers were never as significant among Diaspora Jews as most scholars suggest. If they existed at all, they were isolated and did not have the effect that many suppose. In a sense they were a figment of the scholarly imagination, based on a literary and theological expansion of what Luke says in Acts. We would like to share with you the evidence that has led us to this conclusion.

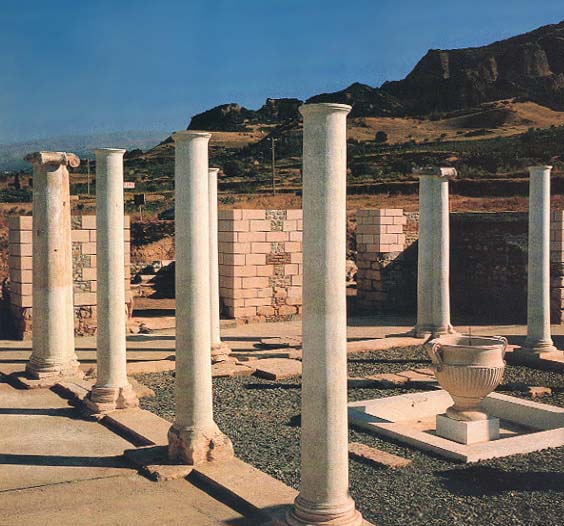

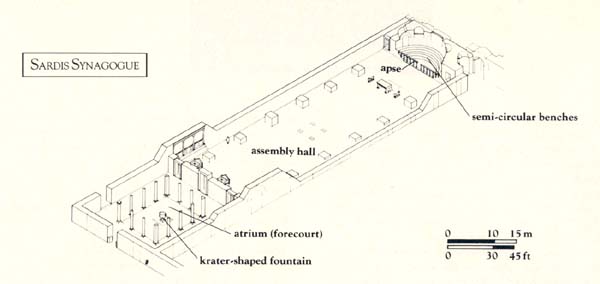

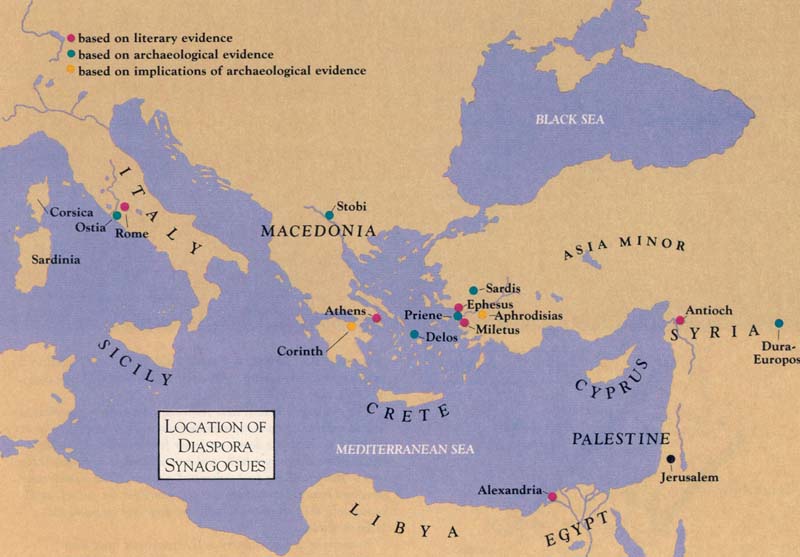

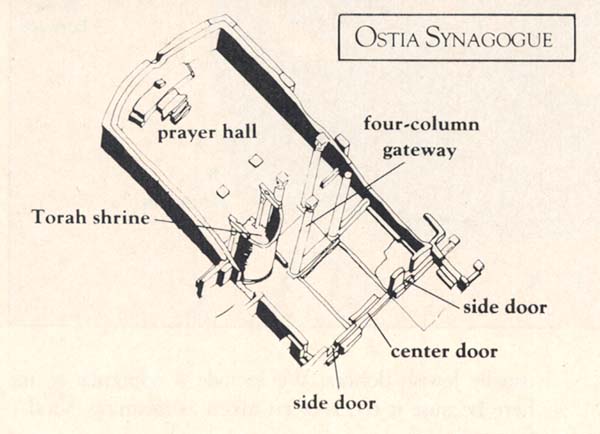

The archaeological evidence for Diaspora Judaism under the Roman empire has recently increased substantially. In the 1960s, well-preserved ancient synagogues were discovered at Ostia, the port of Rome, and at Sardis in western Turkey. Another important Diaspora synagogue is being excavated at Stobi in Yugoslavia.9 Substantial collections of Jewish inscriptions, papyri and artifacts have provided the basis for detailed studies of Jews all over the Roman empire—in the east at Dura-Europos, in North Africa, in Alexandria and in Rome itself.

We now have enough information to permit a fairly detailed reconstruction of Jewish life in the Diaspora based entirely on archaeological evidence.

The archaeological evidence is of equal antiquity with the rabbinic literature and Greek and Latin literary texts, and has the added advantage of coming directly from Diaspora sites. Moreover, the archaeological evidence comes from the Jews themselves, rather than from gentile comments about them in Greek and Latin literature. An examination of Greek and Latin texts will produce many examples of how partial and distorted that “outside” evidence can be.10 And as we shall see, Christian literature, and particularly Acts, also provides an uncertain basis for reconstructing Jewish life in the Diaspora.

The archaeological evidence on which we rely comes mainly from excavated synagogues. This is because the God-fearers are supposedly associated with synagogues, that is, with organized Diaspora Jewish communities.

These synagoguesb date from the first century B.C. to the early seventh century A.D.

A study of these excavations reveals the following:

1. Over 100 synagogue inscriptions have been uncovered. Not a single one uses the term phoboumenos (fearing one) or sebomenos (devout one). Theosebes (plural: theosebeis) (God worshipper) appears apparently ten times, but as an adjective describing Jews, usually Jewish donors. We include a reference to it here because it too is often taken as meaning “God-fearers.”

2. There is nothing in these inscriptions to suggest the existence of an interested, but unconverted group of gentiles who frequented the synagogue. If our only evidence were synagogue inscriptions, there would be nothing to suggest that God-fearers had ever existed.

3. The symbolism used in the synagogue buildings is directed toward the Jewish community, with no apparent attempt to communicate with persons who come from outside this tradition. For example, in the Dura-Europos synagogue (c. 245 A.D.), the paintings display Biblical themes and characters like David, Moses and Abraham, relevant to Jewish community life.11

4. In the Diaspora, the synagogue was probably the only building owned by the Jewish community; it served as the center of the community’s social as well as religious life. It thus played a far more significant role than a synagogue in Palestine. It is not accidental that at least four of the six Diaspora synagogues listed in the footnote were dominated by a Torah shrine that marks the importance of the Diaspora synagogue as a distinctively Jewish center.

5. Diaspora synagogue contact with Christians was rare, despite the fact that the accounts in Acts assume such contact was common. To judge from the material remains, the gentile world in which these Diaspora Jews lived was considerably more pagan than Christian. In third century Dura-Europos, the synagogue was much more elaborate than the Christian building. The Stobi synagogue was rebuilt twice before it was finally displaced by a church building, and that did not occur before the fifth century. At Sardis, excavations have established the prominent position of the Jews in the life of the larger community, but there is nothing in the archaeological evidence to suggest any significant impact of Christianity or Christians on Jewish life in Sardis before the city fell to a Persian invasion in 616 A.D.

In short, none of the supposedly technical terms for God-fearers appears in any of the synagogue inscriptions. Nothing in the excavated buildings suggests the presence of a kind of gentile “penumbra” around the Diaspora synagogue communities. Nor is there any hint in the data that these Diaspora Jews were reaching out toward their gentile neighbors with some kind of religious message.

If interested gentiles—“millions by the first century,” as one source cited earlier suggested—had been accepted as part of Diaspora synagogue life, something should have shown up in the excavations of these synagogues. To date, nothing has!

There is one possible exception: In 1976, a Greek inscription was discovered at ancient Aphrodisias in Asia Minor that some scholars have argued now provides solid archaeological evidence for the existence of God-fearers. Unfortunately, the inscription is still unpublished. Its publication has been assigned by the excavator, Kenan T. Erim of New York University, to Joyce Reynolds of Cambridge University. Miss Reynolds hopes to publish the inscription soon. But until she does, we must base our discussion on a brief prepublication notice Reynolds provided to BAR.c

The inscription appears on a stone that perhaps once served as a doorjamb. Each side of the stone is inscribed. Miss Reynolds dates at least one and perhaps both inscriptions to the third century A.D. One side lists 18 names of a group devoted to learning, who contributed a memorial to the congregation. Three of the men are described as proselytes and two as theosebeis, meaning “God worshipper” or “pious” but sometimes translated “God-fearers.”

The second side of the stone contains two lists of names divided by a blank space. The heading of the upper list has not survived; 55 apparently Jewish names survive in whole or in part in the upper list. The lower list contains 52 names and is headed “And those who are theosebeis.”

The theosebeis bear non-Biblical names, according to Reynolds (with perhaps one exception). The upper list contains mostly recognizably Jewish names.

Miss Reynolds suggests that these names listed on a monument with Jewish names reflects “a solid core of men” who “set a high value upon Judaic tradition, piety and the cooperative virtues, and it appears that their interest in Judaic tradition was on the increase.”12 According to Reynolds, “Here we have theosebeis involved in what must be the study of the law, a category of theosebeis closely associated with Jewish congregations.” Dr. Reynolds concludes in her notice, “To me, it seems that there is a good case for regarding them as what are conventionally called ‘God-fearers,’ gentiles attracted to Judaism, but stopping short of becoming proselytes.”

Does this inscription now prove the existence of a group conventionally called “God-fearers.” Or, are we faced with an inscription that, despite Reynolds’s cautionary notice, other scholars will use to interpret theosebeis as it has been conventionally conceived? Reynolds is not at the point of concluding that theosebeis should carry such theological baggage. She is interested in providing basic information about the inscription, which was found in an area not associated with any building. Reynolds is not trying to prove the existence of a large group of God-fearers in the Diaspora; rather she is describing a connection between one Jewish community and some pious gentiles.

Other texts just as clearly designate gentiles who have never been in contact with Jews at all as theosebes. In literature and inscriptions theosebes does not have a single meaning. In the late second century, Melito, bishop of Sardis, uses theosebes to refer to Christians in general.13 Sometimes theosebes is used to describe persons who are clearly Jews. In other texts, it just as clearly designates gentiles who were never in contact with Jews. For example, in the first book of his History (1.86.2) Herodotus calls Croesus (the sixth century B.C. king of Lydia, who had all the gold) theosebes.14

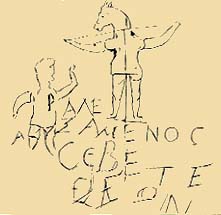

Another example, much closer to the language and date of Acts, is the famous anti-Christian graffito from Rome—from the paedagogium under the Palatine Hill. It shows a boy kneeling before a crucified figure with the body of a man and the head of a donkey. The legend beneath reads: “Alexamenos worships God [sebete theon].” Sebete theon—“worships God”—is precisely the vocabulary found in Acts, but Alexamenos is neither Jewish nor pagan but clearly Christian.15 We are not dealing with an accepted “technical term of one and only one meaning.”

Behind these discussions of technical or quasi-technical terminology in Judaism is often the erroneous assumption that Judaism in the Roman empire was monolithic and everywhere the same,16 and thus that wherever a term appears its meaning will be the same.

The exceedingly important Aphrodisias inscription, offers an opportunity for a full exploration of the term, perhaps the first in which all the affected disciplines might participate.

What is behind this reading of this ancient evidence? We see at least two broad misconceptions, one about the Jews of antiquity and their friends and associates, the other about the New Testament.

Many scholars seem to assume that in Diaspora Judaism whenever someone is sympathetic to Jews or is pro-Jewish, that means he or she is interested in the Jewish religion. But that is not necessarily true. It is quite possible that gentiles were friendly toward Jews simply as neighbors or fellow-townspeople. This was no doubt the case at Sardis, where excavations have uncovered a synagogue in the heart of the city and inscriptions that reflect Jewish involvement in the gentile life of the city (but not gentile involvement in the religious life of the synagogue).17 The synagogue at Sardis suggests that gentiles acknowledged that Jews had a proper place in the city; they belonged there as an ethnic minority.

If we persist in seeing Judaism in antiquity first of all as a religion, it will be difficult to understand the openness of many non-Jews toward Jews in anything other than religious terms. But to have Jewish friends or to take a positive stand toward Jews need not mean—either today or in antiquity—an interest in converting.

The other misconception has to do with the nature of the evidence that the New Testament provides.

Now that we have placed the archaeological evidence in context, we can come back to Acts to determine whether it should be used as a foundation to argue for the widespread existence of God-fearers.

In order to understand this literary evidence, we must understand the purpose of the text, in which the supposed references to God-fearers are found.

New Testament writers were not trying to tell their readers what they already knew, namely, the facts surrounding the events of the early Church. These writers were not trying to describe the events that had occurred. They were interested rather in interpreting the meaning of those events. They wanted to tell why the church existed, what the Cross meant, why Jesus was the Messiah, why there was a split between the Jewish Christian movement and the Jews. Their concern was not simply to give an account of what happened, but rather to provide an interpretive portrait in words of the events surrounding the origin of the Church. The New Testament is not so much a history book, in a modern sense, as a collection of early Christian sermons and letters.

Modern preachers and commentaries often give Luke credit for describing in Acts how Christianity moved from the Jews to the gentiles. But this is a historical question that was never really at the center of Luke’s concerns. Recent studies of Acts have shown the extent to which it is a literary composition—or, perhaps, more accurately, theology in narrative form—rather than a historical record. In Acts, Luke wants to provide an edifying story of the way Christianity began.

To appreciate how non-historical Luke can be in Acts, we need only compare an event described by him with the same event described by Paul—for example, the Jerusalem Council, which considered whether one must be a Jew to be a Christian. Compare Paul’s account of the Jerusalem Council in Galatians 2 with Luke’s account of it in Acts 15. An objective reader must conclude that either Luke and Paul are talking about two different events or they are describing the same event from entirely different viewpoints for different audiences. Paul was probably more nearly correct historically, but both writers had a story to tell, each from his own point of view in order to make his own case. It is doubtful that we can fully reconstruct what actually happened from either text. Neither account was concerned with providing data for such a reconstruction. Both were far more interested in defending their view of the need for, and the results of, the Jerusalem Council.

Acts is essentially an argument for the early Church’s mission to the gentiles, not a description of that mission. Searching the text for historical details is a frustrating endeavor because Luke is constantly interpreting events instead of merely describing them.

Similarly with Paul: His letters are proclamation rather than description. Neither Paul nor Luke was concerned with recounting history. Each had a passion for his message. As a result, it is impossible to reconcile Paul’s theology or the chronology of his career, as found in Acts, with the description of those same elements in the Pauline epistles.

At first glance, the God-fearers referred to in Acts may appear to be a group of real people who “sympathized with Judaism and enjoyed a recognized status upon the fringes,” as Salo Baron has described them.18 We must question the use of these references as historical data. New Testament scholars have provided many examples of Luke’s alteration and amplification of his sources in the service of the story he wishes to tell. His way of presenting Christianity is narrative. For too long he has been taken as a historian in the modern sense; the result has been a distorted picture of the religious situation of the first century.

Luke’s literary creativity served the best of purposes; but at the same time it requires us to be cautious in attempts to use Acts as a historical source, especially when conclusions from Acts are not independently supported by other evidence.

Here there is no independent evidence. The other evidence, such as it is—inscriptions and classical and rabbinic texts—is almost always “explained” with reference to Acts. Indeed, if it were not for the references in Acts, we would not have the term “God-fearer” at all.

The point Luke is making is clear: Christianity’s path to the gentiles was—had been—through the Jews, in contrast to Paul, who wished to appeal directly to the gentiles.

Luke’s narrative serves his viewpoint. He is telling us good news and bad news. The bad news is that Christianity has been rejected by most Jews in Palestine and the Diaspora. The new religion must move beyond them. Luke has therefore concluded that the time has passed when Jews in considerable numbers might be expected to become Christians.

The good news is symbolized by the God-fearers, the gentiles whom the Jews had begun to attract before Christianity came onto the scene. In Luke’s view in Acts, these gentiles, thanks to Peter and especially to Paul, inherited the Christian message. Christianity is becoming more and more a gentile religion; Christianity’s outreach to the gentiles is legitimized by the broad based “existence” of the God-fearers surrounding the synagogues of the Diaspora Jews, representing an earlier outreach to gentiles by the Jews. This Jewish outreach to these gentiles justifies Christianity’s outreach to them, in Luke’s view.

Luke uses the God-fearers as a device to show how Christianity had legitimately become a gentile religion, without losing its roots in the traditions of Israel. The Jewish mission to the gentiles represented by the God-fearers was intended to be ample precedent for Christianity’s far more extensive mission to the gentiles, a mission that had in fact enjoyed considerable success.

It is significant that the word synagogue is not used at all in Paul’s letters. In Acts, on the other hand, the term is used frequently, almost always as the place where Diaspora Christian missionary preaching begins. Paul’s first act as the “Apostle to the gentiles” is to preach in a synagogue (Acts 9:20). Luke’s point is clear: only when the Jews rejected the Christian message did the Diaspora mission turn to gentiles.

When Paul in Acts withdraws from the synagogue, angered by Jewish rejection of his message, we might expect to hear more about the God-fearers as the focus of Paul’s mission. But the fact is that they then disappear from the story. We never hear of them again. It is no accident that we have no more God-fearers after Acts 18:7 and no more “going into the synagogues” after Acts 19:8. These two themes go together, and after Acts 19:9 neither God-fearers nor synagogues have any further function.

The God-fearers are onstage as needed, offstage after they have served their purpose in the plot. Once his point has been made, Luke can let the God-fearers disappear from the story. The abruptness with which they vanish would surely be difficult to account for, if, as Martin Hengel suggests, Luke was himself a God-fearer.19 But they simply disappear; there is no further reference to them in the New Testament and no clear independent record of them in the material evidence from the Classical world. Thus, Acts cannot be used as evidence that there ever were such groups in the synagogues of the Roman empire.

It is a tribute to Luke’s dramatic ability that the God-fearers have become so alive for the later church. But the evidence from Paul’s own letters and now the negative evidence from archaeology makes their historicity, as conventionally defined, questionable in the extreme.

If we are right that “the evidence presently available is far from convincing proof for the existence of such a class of gentiles as traditionally defined by the assumptions of the secondary literature,”20 this has some important implications for both Christian and Jewish history.

The straight-line picture of the expansion of Christianity given in Acts runs from the Jews to the God-fearers, to the gentiles. That, however, is a simplified version for the purpose of Luke’s story; rather, Christianity expanded over a broad front, and in doing so, used several religious “languages” at the same time—with inevitable internal conflicts, attested as early as Paul’s letters.

This means that Christianity must be seen as much more varied in the first two centuries after its birth. The New Testament itself is a record of the diversity of Christianity in the first century. The seeds of a multifarious church were sown in the early years of the Christian mission.

The God-fearers have often been used to demonstrate the inadequacy of Judaism in the Greco-Roman period—what Martin Hengel has termed the Jewish religion’s “stoop[ing] to constant and ultimately untenable compromises” in order to make a place for itself in an alien world. But the New Testament provides no evidence for such a failure, if the God-fearer texts are properly understood. In fact, quite the opposite is the case. The vitality of first-century Judaism, especially after the Roman destruction of the Jerusalem Temple in 10 A.D., is reflected in Judaism’s powerful impact on the Greco-Roman world. The vehemence of the church’s polemic against the Jews almost certainly suggests that the synagogues of the Diaspora made no compromises with the Christian mission.

A proper understanding of Acts, coupled with the new evidence from excavations, indicates that many Diaspora Jews did not feel like aliens. This is perhaps most clearly shown from the excavations at Sardis. The Jewish community there was a very old one. Generations of Sardis Jews were natives of Anatolia (modern Turkey); they were not refugees, immigrants or slaves from troubled lands farther east. By the time the synagogue and the city were sacked by the Persians in the seventh century A.D., Jews had lived there for nearly a millennium, perhaps more; and almost from the beginning, they apparently enjoyed considerable standing with the various gentile authorities.21 It would not be unreasonable to assume that an established and respected Jewish community had a profound religious, philosophical and social effect on the city in which it lived. The values expressed in the synagogue would certainly have influenced the values of the community, just as they do today.

Finally, Jewish missionary activity conducted from these synagogues may have been much less extensive than was once thought to be the case. The only reference to a proselyte in the New Testament outside Acts 2:11, 6:5 and 13:43, is Matthew 23:15, where Matthew rebukes the scribes and Pharisees saying “you traverse sea and land to make a single proselyte, and when he becomes one you make him twice as much a child of hell as yourselves.” The polemic of the verse is obvious. (Nothing similar appears in the parallel texts of the other two Synoptic Gospels, Mark and Luke.) In the absence of other evidence of Jewish missionary activity from the Roman Diaspora we can base no sound historical conclusions on the New Testament references.

Understanding “the disappearance of the God-fearers” enables us to reconstruct more accurately several aspects of Christian and Jewish history.

Obviously there will be a continuing discussion of the fascinating issues raised in this and the following two articles. Scholars, including our co-author, A. Thomas Kraabel, will next be pursuing the subject in late November in Atlanta at the Hellenistic Judaism section of the annual meeting of the Society of Biblical Literature. In addition, one or more of the scholars here may make a response in a forthcoming issue of BAR; it should be noted that MacLennan and Kraabel did not see the Tannenbaum or Feldman articles that appear in this issue until shortly before publication when it was not possible to revise their article to make direct reference to the other two articles.—Ed.

MLA Citation

Footnotes

Diaspora is the term used for Jews dispersed outside the land of Israel. The word is used for both the people and their communities.

Delos, on that island in the Aegean Sea (first century B.C. to second century A.D.); Ostia, in Italy (fourth century A.D.; the earliest synagogue may be as early as the first century A.D.); Dura-Europos, in Syria (the building is second century A.D. to 256 A.D.); Sardis, in Asia Minor (second or third century A.D. to 616 A.D.); Stobi, in Macedonia (fourth century A.D.; earlier synagogues at the site date to the third century A.D. or earlier); Priene, in Asia Minor (third or fourth century A.D.).

For more on the Aphrodisias inscription, see “Jews and God-Fearers in the Holy City of Aphrodite” by Robert F. Tannenbaum, in this issue.

Endnotes

K. G. Kuhn and H. Stegemann, “Proselytes,” in Pauly-Wissowa, Realenzyklopädie der klassischen Altertumswissenschaft (Stuttgart, 1893– ), suppl. ix (1962), p. 1260, cf. pp. 1248–1283.

David Flusser, “Paganism in Palestine,” in Compendia Rerum Judaicarum ad Novum Testamentum I.2, ed. S. Safrai and M. Stern (Arsen, 1976), p. 1097.

A. Thomas Kraabel, “Greeks, Jews and Lutherans in the Middle Half of Acts,” in Christians Among Jews and Gentiles: Essays in Honor of Krister Stendahl, ed. G. W. E. Nickelsburg (Philadelphia, Fortress, 1986).

Robert Maddox, The Purpose of Luke-Acts (Edinburgh: T. & T. Clark, 1982), p. 16; Kraabel, “The Disappearance of the ‘God-Fearers,’” Numen 28 (1981).

In the past half-century some of the most influential treatments of this issue have been K. Lake’s “Proselytes and God Fearers” in F. Foakes Jackson and Lake, The Beginnings of Christianity I. The Acts of the Apostles, vol. 5 (London, 1933), pp. 74–96 and the extended note to Acts 13:16 in H. L. Strack and P. Billerbeck, Kommentar zum neuen Testament aus Talmud und Midrasch, vol. 2 (Munich, 1924), pp. 715–723. More recent studies include: Louis H. Feldman, “Jewish ‘Sympathizers’ in Classical Literature and Inscriptions,” Transactions of the American Philological Association 81 (1950), pp. 200–208. P. Markus, “The Sebomenoi in Josephus,” Journal of Semitic Studies 14 (1952), pp. 247–250; M. Wilcox, “The God-fearers in Acts: A Reconsideration,” Journal for the Study of the N.T. 13 (1981), pp. 102–122; Kraabel, “The Disappearance of the ‘God-Fearers,’” pp. 113–126; Thomas M. Finn, “The God Fearers Reconsidered,” Catholic Biblical Quarterly 47.1 (1985) pp. 75–84.

Kraabel, “The Diaspora Synagogue: Archaeological and Epigraphic Evidence Since Sukenik,” Aufstieg und Niedergang der romischen Welt II. 19 (1979), pp. 477–510; and “Social Systems of Six Diaspora Synagogues,” in J. Gutmann, ed., Ancient Synagogues: The Current State of Research (Chico, CA, 1981), pp. 79–91. Kraabel and Eric M. Meyers, “Archaeology, Iconography and Non-Literary Written Remains,” Chapter 9 of Early Judaism and Its Modern Interpreters, edd. R. A. Kraft and A. W. E. Nickelsburg, vol. II, The Bible and Its Modern Interpreters, ed. D. A. Knight, forthcoming.

Texts are assembled in M. Stern, Greek and Latin Authors on Jews and Judaism I–III (Jerusalem, 1974–1984).

For an introduction and further bibliography, see N. Peterson, Literary Criticism for New Testament Critics (Philadelphia, 1978), pp. 81–92.

Kraabel, “The Roman Diaspora: Six Questionable Assumptions,” Journal of Jewish Studies 33 (1982), particularly pp. 453–454.

Kraabel, “Impact of the Discovery of the Sardis Synagogue,” in Sardis from Prehistoric to Roman Times, ed. G. M. A. Hanfmann, (Cambridge, MA, 1983), pp. 178–190.