The Historical Importance of the Samaria Papyri

025

When the Ta‘âmireh bedouin penetrated the Daliyeh cave (as described in the previous article by Paul Lapp) they found within more than 300 skeletons lying on or covered by mats. The bones were mixed with fragments of manuscripts. These manuscripts were not burial documents, but everyday business records. The artifacts found in the cave were not traditional burial objects, but ordinary things for daily use. A grim conclusion seems clear. The Daliyeh cave was not a burial ground but, rather, a refuge which murder turned into a tomb.

The best hypothesis to explain the 300 skeletons or more found by the Ta‘âmireh seems to be that a large number of refugees fled to the cave and were then discovered by their pursuers, who built a large fire at the mouth of the cave and succeeded in suffocating everyone inside. The covering with matting might have been the last tender act by survivors of the catastrophe.

Can we go further and suggest a more specific historical background to this holocaust?

Since the dating evidence, which I shall discuss later, suggests that the dread event occurred during the last third of the fourth century B.C., it is there that our historical attention must be focused. A precise occasion easily suggests itself.

Although the people of the city of Samaria initially ingratiated themselves with their foreign ruler Alexander the Great, they later burned alive Andromachus, Alexander’s prefect in Syria. The act was not only a heinous crime, it was the first sign of revolt in Syria-Palestine. Alexander returned in all haste to Samaria and took vengeance on the murderers who were “delivered up to him”, according to the ancient historian Curtius Rufus.

Alexander destroyed the city of Samaria. Archaeologists have uncovered late fourth century towers at Samaria which were built in Greek design rather than Palestinian. This suggests that Samaria was resettled by Greek Macedonians after its destruction; and indeed both Eusebius and Jerome tell us that this was the case. In addition, excavations at Shechem reveal that that city was rebuilt in the late fourth century after a long abandonment. This is probably to be explained by the fact that the Samaritans who fled Samaria rebuilt Shechem as their new capital.

But not all the Samaritans went to Shechem. The leaders who were implicated in the rebellious acts that led to the prefect Andromachus’ death fled Samaria in haste on learning of Alexander’s rapid march on the city. They probably followed the main road down the Wadi Far’ah into the wilderness, and found temporary refuge in the Wadi ed-Daliyeh cave.

The number who fled was large, and included whole families fairly well supplied with food. Their origin and status is well attested by their seals and their legal documents found 2300 years later by the Ta‘âmireh.

Alexander’s men discovered the Samaritan leaders in the cave either by assiduous search or, more likely, by information received from their fellows who remained in Samaria.

Presumably, Alexander’s troops then lit a fire at the mouth of the cave and waited for its occupants to slowly suffocate. 026Examination of the papyri and sealings gives rise to mixed feelings. On the one hand, the Samaria Papyri (as they are known to scholars) are in an advanced state of decay—worm eaten, and, for the most part, in small fragments. Even the best preserved papyrus, Papyrus 1, is incomplete. Contrary to our expectations, the small fragments rarely join to the larger pieces of papyrus. We are in possession only of the last remnants of a very large corpus of documents.

On the other hand, there is no doubt that, however fragmentary, the papyri are of extraordinary importance.

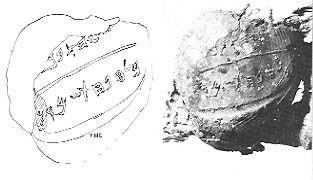

One of the first items to come to our attention was a sealing affixed to the remnants of Papyrus 5 inscribed in a clear Palaeo-Hebrew script which read: “ … yahu, son of [San] ballet, governor of Samaria.”

The governor of Samaria had affixed his seal to this papyrus.

Another papyrus fragment also mentions Sanballat. The last line on the reverse of this fragment reads, “this document was written in Samaria.” Above, on the preceding line, partly broken, appears the names of the officials before whom the document was executed: “[before Yes]ua’ son of Sanballat (and) Hanan the prefect.”

A Sanballat is mentioned frequently in the Bible. (See, for example, Nehemiah 2:10, 19; 4:1; 6:1, 2, 5, 12, 14; 13:28.)

We are of course intrigued by the fact that the governor of Samaria mentioned in the Daliyeh finds had the familiar name of the governor of Samaria about 50 years earlier, in the days of Nehemiah.

Nehemiah’s Sanballat is also mentioned in a papyrus from Elephantine in upper Egypt. He is well known as the devious and malicious enemy of Nehemiah. He was governor of the province of Samaria in 445 B.C., when Nehemiah arrived in Zion; by 410 B.C. Sanballat was an aged man, whose son Delaiah acted in his name. Sanballat gained notoriety in the Bible for his opposition to the restoration of the walls of Jerusalem, and for conspiring against the life of Nehemiah, in league with Tobiah, the Jewish governor of Amman, and Gashmu (Geshem), king of the Qedarite league.

Nehemiah, prevailed, of course, proving as wily as he was pious. He fortified Jerusalem, increased its population, and completed his first tour of duty as governor in 433 B.C.

Upon returning to Jerusalem after an absence of some length, Nehemiah discovered that the son of the Zadokite high priest and the daughter of the hated Governor of Samaria, Sanballat, had been joined in a diplomatic marriage uniting the two great families of Judah and Samaria (Nehemiah 13:28). Nehemiah in righteous indignation chased the bridegroom out of Jerusalem, according to Josephus.

The Zadokite high priest was succeeded by his son Johanan. Apparently Johanan’s brother—a man named Jesus—was also laying claim to the high priesthood. So Johanan killed his brother in the Temple. So dreadful was the event that the Persian governor of Judah who succeeded Nehemiah entered the Temple by force, defiled it, and imposed a heavy tribute on the Jews for seven years.

In the Antiquities of the Jews, Josephus tells a somewhat similar story with some but not all of the same names; the plot is, however, played out in the era of Darius III and Alexander the Great (about 100 years after Nehemiah’s time). Sanballat, appointed governor of Samaria by Darius III, arranged a marriage between his daughter and the brother of Johanan the high priest in Jerusalem. The bridegroom again was expelled and retired to Samaria. This was the occasion, according to Josephus, for the building of the Samaritan temple on Mount Gerizim. Sanballat set up his son-in-law in business, so to speak, providing him with his own temple.

In the past, scholars viewing these two similar accounts were incredulous. Professor Cowley’s sentiment was typical: “The view that there were two Sanballats, each governor of Samaria, and each with a daughter who married a brother of a High Priest at Jerusalem is a solution too desperate to be entertained.” Many historical constructions were attempted to provide a solution. Most saw the account of Josephus as a secondary reflex of Biblical Sanballat.

The probable solution to the crux is that Sanballat (I) was governor of Samaria in Nehemiah’s time (c. 445 B.C.) and another Sanballat (III) was governor of Samaria in the time of Darius III and Alexander the Great (c. 335–300 B.C.). In between (early in the fourth century) Sanballat (II), of the Samaria papyri, served as governor of Samaria.

In short, with the appearance of Sanballat II 027in the Samaria papyri, most if not all objections to a Sanballat III melt away.

We know that it was a regular practice in the Achaemenid empire for high offices such as satrap or governor to become hereditary. It is evident that the descendants of Sanballat held the governorship of Samaria for several generations. Moreover, we know that the practice of paponymy (naming a child for its grandfather) was much in vogue among the Jews and surrounding nations precisely in this era.

We can reconstruct with some plausibility, therefore, the sequence of governors of Samaria in the fifth and fourth centuries. The Biblical Sanballat was evidently the founder of the line. He was a Yahwist, giving good Yahwistic names to his sons Delaiah and Shelemiah. This Sanballat must have been a mature man to have gained the governorship, and in 445 B.C., when Nehemiah arrived, no doubt Sanballat was already in his middle years. His son Delaiah acted for his aged father as early as 410 B.C. The grandson of Sanballat, Sanballat II, evidently inherited the governorship early in the fourth century. Sanballat III succeeded to the governorship in the time of Darius III and Alexander the Great.

Josephus is not wholly vindicated. It is clear that he identified Biblical Sanballat and Sanballat III, jumping from the fifth to the late fourth century. But we can no longer look at the Judean-Samaritan intermarriage Josephus describes with the same historical skepticism. The names and relationships are not all identical in the two stories, but it appears that the noble houses of Samaria and Jerusalem were willing to intermarry despite the ire of certain strict Jews. This intermarriage is evidence that the final and irreversible schism between the Jews and the Samaritans did not come, as an earlier generation of scholars supposed, in the time of Ezra and Nehemiah. This is consistent with further evidence that the schism was as late as the fourth century B.C. The religion of Samaria is clearly derived from late Judaism Its feasts and law, conservatism toward Torah, and theological development show no real evidence of archaism or religious syncretism. Even late Jewish apocalyptic left its firm imprint on Samaritanism. For these and other reasons, scholars have increasingly been inclined to lower the Samaritan schism into the fourth century B.C.

We learn much from the mention of Sanballat, Governor of Samaria, in the Daliyeh papyri. But these papyri will eventually tell us much more. They will provide important new material for the description of social institutions in Persian Palestine, for studies in the history of law, and for description of the linguistic and orthographic evolution of Aramaic in the West.

Although the amount of epigraphic material is small—the largest papyrus contains only 12 short lines of script—the mere description of it whets the scholar’s appetite.

For example, one papyrus records the sale of a slave (Yehohanan son of Se’ilah) to a certain Yehonur (a man who figures several times in the papyri); the seller is Hananiah; the price is thirty-five pieces of silver (shekels). It is of note that all three principals bear Yahwistic names.

The papyri also include several date formulas. Indeed the most important fact in the largest and best preserved papyrus (Papyrus 1) is its date formula: “on the twentieth day of Adar, year 2 (the same being) the accession year of Darius the king, in the province of Samaria … ” Only one Achaemenid king died in the second year of his reign, Arses, who was slain by the infamous eunuch Bagoas, and was succeeded by Darius III. Thus the papyrus was written on March 19, 335 B.C.

Other papyri date from the early reign of Artaxerxes III, including Papyrus 8 written on March 4, 354 B.C., “before [Ha] naiah governor of Samaria.”

The earliest dated piece belongs between the thirtieth and fortieth year of Artaxerxes II, that is, between 375 and 365 B.C.

Thus the range of dates extends from about 375 B.C. down to 335 B.C. or slightly later, some forty years. This covers one of the most impenetrable eras in the history of Palestine.

These absolutely (not relatively) dated writing samples are of extraordinary importance in the typological study of scripts, and have already helped date other ancient writings.

Perhaps twenty pieces of the finds are worthy of being numbered as “papyri.” There remain literally hundreds of small fragments, few of which can be joined to each other or the larger papyri. The original deposit may have been in excess of a hundred documents. In addition, two of the seals, one the governor’s seal, are inscribed, both in Palaeo-Hebrew script.

The primary destructive agent seems to have been worms rather than rot. Many of the rolled documents, unfortunately, were devoured through, leaving patterns like paper dolls when the papyri were opened. One is forced to the grisly speculation that the worms which multiplied in the heaped corpses of the dead also attacked the papyri.

(For further details see Discoveries in the Wâdi El-Dâliyeh, edited by Paul W. Lapp and Nancy L. Lapp (Cambridge, American Schools of Oriental Research 1974), Chapter 3, from which this article has been adapted.)

When the Ta‘âmireh bedouin penetrated the Daliyeh cave (as described in the previous article by Paul Lapp) they found within more than 300 skeletons lying on or covered by mats. The bones were mixed with fragments of manuscripts. These manuscripts were not burial documents, but everyday business records. The artifacts found in the cave were not traditional burial objects, but ordinary things for daily use. A grim conclusion seems clear. The Daliyeh cave was not a burial ground but, rather, a refuge which murder turned into a tomb. The best hypothesis to explain the 300 skeletons or more found […]

You have already read your free article for this month. Please join the BAS Library or become an All Access member of BAS to gain full access to this article and so much more.

Already a library member? Log in here.

Institution user? Log in with your IP address or Username