040

A deep fissure runs through Biblical studies today. On one side are those who maintain that the Bible contains much reliable history; on the other side are those who say the Biblical texts were written much later than the events they describe and have little or no historical value. Some, like Israel Finkelstein, the co-excavator of Megiddo and the subject of an interview in our previous issue, portray themselves as centrists; Finkelstein thinks many key Biblical texts date to about the seventh century B.C. and he is dubious about texts that claim to report on earlier events.

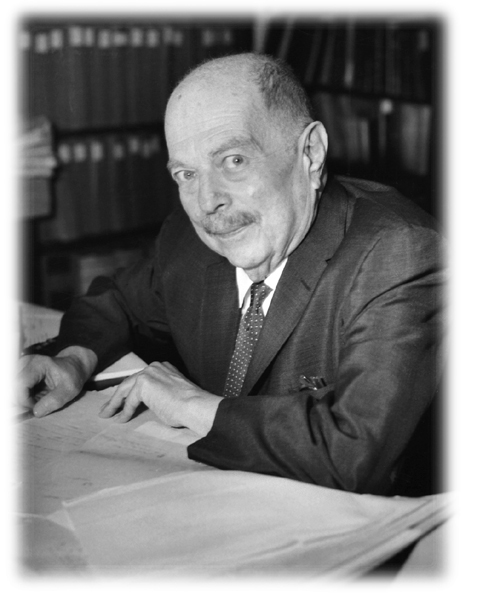

Another scholar we interviewed recently is Avraham Malamat, long associated with the Hebrew University of Jerusalem. Malamat believes we can recover much about the earliest periods of Biblical history—in its broad outlines if not in detail. Unlike those of his colleagues who never get past the minutiae of history, Malamat is interested in what Goethe called die Grossen Zuege, the grand sweep of matters. Malamat is particularly well known for his expertise on the many thousands of inscribed cuneiform tablets from ancient Mari, a second millennium B.C. kingdom on the Euphrates River in modern Syria. The tablets reveal a culture with striking similarities in language and customs to ancient Israel. For Malamat, Mari provides an important source for what he calls the “protohistory” of Israel.

BAR editor Hershel Shanks recently spoke with Malamat about Mari and ancient Israel, Malamat’s European-Jewish upbringing—born in Vienna, he was recently awarded an honorary doctorate by that city’s medieval university—and the sometimes quirky scholars he has known in his long and distinguished career.

041

Hershel Shanks: Avraham, whenever I think of you, I think that you’re almost as much a Viennese as a Jerusalemite.

Avraham Malamat: I was born in Vienna, but left at the age of 13-and-a-half.

HS: But you’ve still got that Viennese charm, you’ve got that Viennese intellectualism, Viennese detail (13-and-a-half, not just 13). You almost look Viennese. You imbibed that by the time you were 13.

AM: It remained somehow. I left in 1935, three years before Hitler came to Austria.

HS: Why?

AM: My father was a hot Zionist. He wanted to leave already in 1905. But he married and they had two children. So he left in 1935, 30 years after he really wanted to leave. My mother came with him. She was Viennese.

HS: Was he Viennese also?

AM: No, he was from Kishinev [in Moldova]. You must have heard of the famous Kishinev pogroms in 1903 and 1905. Both my father’s parents were killed on the same night in the second Kishinev pogrom. He was taken by the Alliance Israelite [a Jewish organization founded in Paris with a long history of helping Jews of persecuted communities] to Vienna. He wanted to get to Palestine. But the Alliance Israelite kept him in Vienna for schooling. He was 13 years old. Then after nine years the First World War broke out.

My mother was also Zionist. It was a Zionist family. My mother was religious [observant] but my father was not. He ate pig. When he courted my mother, he ordered pig—swine! My mother was shocked. That a Jew from Kishinev should eat that!

HS: How did you decide to become a Biblical scholar?

AM: Well, in my first year at the Hebrew University, I studied many subjects, but I was excellent in Hebrew grammar. I was so good already that in grade school, I got a 97 in Hebrew grammar and the teacher gave me the examinations of the other students to correct. In my first year at Hebrew University—I finished in three years—I started in Semitics and Bible. Then suddenly I met [Benjamin] Mazar, Dr. Meisler at that time [before he changed, as was common, to a Hebrew name]. He said it’s stupid what I study. “You come to me and study Biblical history.” I said, “I will finish the university in one to two months. How can I lose four more years because of you?” He said, “I will make a deal with you. You take the examination now; you know enough. Later, you will sit two years in my class.” So I agreed. It was Mazar who drew me in, but I would have come this way anyway, because I also went to the école Biblique [et Archéologique Française, the French Dominican school in Jerusalem]. I studied there four years. I could have been a Dominican priest, but I didn’t take the examinations. I studied with [Father Roland] de Vaux, with [Father Felix-Marie] Abel and others. I was the only Jew at the time who studied in the école Biblique. Yigael Yadin came there to read—in the best library in the world, in my opinion. They are very proud at the école Biblique that Eliezer Ben-Yehuda wrote his Hebrew dictionary [reviving Hebrew as a modern language] in their library, and Yehezkel Kaufmann wrote his seven-volume History of the Religion of Israel in their library.a

HS: After you studied with Mazar for two more years, did you get a B.A. from Hebrew University?

AM: An M.A. I then started work on my doctorate—on the Arameans. I finished only in 1951 because there was the War of Independence [in 1948].

From 1952 to 1954 I was in America at the Oriental Institute [of the University of Chicago] for post-doctoral studies. I studied with the greatest scholars of the time. I studied under [Benno] Landsberger, who did not like Mazar. I studied under Gelb. Do you know the name Gelb?

HS: Ignace Gelb? [He started the Chicago Assyrian Dictionary and served as its editor from 1947 to 1955.]

AM: Yes. He converted to Christianity.

HS: Gelb was Jewish?

AM: Yes. He was from Galicia (Tarnow, Poland). He became Christian. I had very good relations with Gelb. He once showed me a letter in Yiddish, and I couldn’t read it, so he read it to me himself.

And there was Leo Oppenheimer who was from Vienna, but we never spoke German. With Landsberger I spoke German. He was from Leipzig, originally from Bohemia. [He was deprived of his chair at the University of Leipzig by the Nazis in 1935 and left Germany for Turkey.] He was the greatest Assyriologist in the world. 042He said, “Nobody before me was like me and nobody after me will be a Landsberger.” He had a point. He said, “In my generation, I can view the entire Assyrian material, but in 20 years, it will be impossible. Nobody will be able.” He was also not modest. He said, “I deserve the Nobel Prize for Assyriology, but it doesn’t exist.” He was very arrogant, but very good to students. He invited me almost every other evening to his home.

HS:Are you a Biblical scholar or an Assyriologist?

AM: Neither. I call myself a Biblical historian. I am a scholar on the history of the Biblical period.

HS: But you are an expert in Akkadian [the language of Assyria] and Babylonian texts.

AM: But with Landsberger I studied also Hebrew. He knew Hebrew better than anyone. So I studied Assyriology, but as a by-product, Hebrew.

HS: What is your recollection of Mazar as a man, as a scholar?

AM: I am very ambivalent. He was a very warm person and enthusiastic for his field and his students. He had wonderful ideas, but you have to check if somebody saw it before you, and this he hardly ever did. Some of his ideas were known before him. Then, I didn’t trust his flair for theories. He took theories out of his pockets and pronounced them. On the other hand, he was very devoted to the field. He was brilliant. Another Bible teacher would look for an hour at a passage and Mazar would look for five seconds and get the meaning of the passage.

HS: Did you also study archaeology?

AM: Yes. I studied one year with [E.L.] Sukenik. He was Yigael Yadin’s father. Sukenik was very lazy in preparing for class, and he made terrible mistakes. Once I was at Beth-Shean with him, and he spoke about another place as if it was Beth-Shean. Somebody had to tell him, “No. Here is Beth-Shean.”

HS: Did you have any contact with [William Foxwell] Albright [considered the dean of American Biblical archaeologists]?

AM: Yes. I edited the Albright jubilee volume of Eretz Israel in 1969 [honoring Albright]. I came to Johns Hopkins to visit him. He invited me for lunch. Then he 043took me to his home and at seven o’clock I had dinner with him. That means he was flowing with ideas. Great ideas! I could speak with him about Mari texts. He was very good, but he was somehow, how do you call it, fundamentalistic. He believed too much in the Bible. He was not critical enough. Landsberger always shouted about Albright that he was a fundamentalist and that I shouldn’t become like him. I was present when Albright visited Landsberger. Albright told him “I am not married to Assyriology, I am only betrothed to Assyriology.” Landsberger replied, “No, dear Albright, you are married to archaeology. I will tell you something more. Some of your publications are better than mine. You have intuition, great intuition.” You could really learn much from Albright.

HS: How did you become involved with Mari?

AM: At the École Biblique. I saw there the first publications of Mari.

HS: What is Mari?

AM: Mari is a city in Syria about 50 or 75 kilometers from the border between Syria and Iraq. Between 20,000 and 25,000 cuneiform tablets were discovered there by [the French archaeologist] André Parrot. He was a young man working at the Louvre in 1933. He heard that some Arabs had found a statue there. Within two months he was there with an excavation team. He made his great discoveries at Mari in 1936.

For me, Mari is a treasure house, because I view the entire protohistory of Israel through Mari. Mari has much in common with the Bible. The language there was West Semitic [similar to Hebrew]. The tablets come from the 18th century [B.C.] and Albright contended Abraham lived in the 18th century. I don’t say that. Maybe Abraham didn’t exist. In the Bible you have only three generations of patriarchs—Abraham, Isaac and Jacob. In reality, the protohistory of a people can be a thousand years, five hundred years. And this time it goes back to Mari. Mari flourished in the 18th century. I don’t say the Israelites came from Mari, or that Abraham came from Mari, but you have there the impression of the forefathers and the folkways of the protohistory of Israel. I never 044use the term “patriarchal age.” I don’t think Abraham, Isaac and Jacob have a well-defined time period. They float between the 13th century [B.C.], which is taken today to be the beginning of Israel, to the 23rd century [B.C.]—a thousand years. In the Bible it is telescoped, like an accordion. And Mari is the most important find for the early period of Biblical Israel. The city’s size is only 540 dunams [135 acres]; Hazor [in northern Israel] is bigger, but the expedition found about 20 archives [in Mari].

HS: There are also some beautiful frescoes in Mari.

AM: Yes! Wonderful.

You know who this lady is [showing me a picture of a clay mold from Mari]? She is depicted on a mold, for cakes. You bake and then you eat the cake—and you get the lady. I have an idea about this lady. This lady is naked and might be [the goddess] Ishtar. Jeremiah condemns the holy cakes made for Ishtar, the Queen of Heaven [Jeremiah 7:16–20 and particularly Jeremiah 44:19]. In Mari you have the same thing 1,200 years earlier!

HS: Of the 25,000 tablets, how many have been translated?

AM: I would say 8,500. There are 20 Mari tablets about Hazor [a major city in the 18th century B.C., and the only city in Israel that is mentioned in the Mari texts]. There might be 60 or so, since 8,500 is one-third of the total. The language of the tablets is Akkadian.

HS: What is Akkadian?

AM: Akkadian is the language of the Assyrians in the third and second millennium B.C. West Semitic Akkadian is close to a kind of Hebrew.

But Mari is a special dialect. The dialect is 90 percent Akkadian but 10 percent Hebrew. For example, “goy” does not exist in Akkadian, but it does in Hebrew.

HS: Meaning [in the plural] “the nations.”

AM: Yes. Whenever [modern] translators don’t understand a word [at Mari], they open the Hebrew dictionary.

In what language did the king of Mari speak to his wife? Hebrew or Akkadian? I think in Hebrew. But when he went into the courts, he spoke Akkadian with the dignitaries.

HS: Why do you think he spoke to his wife in Hebrew?

AM: Because that was his national, his mother tongue. His mother tongue was a kind of Hebrew.

HS: So far east?

AM: Yes, not exactly today’s Hebrew, but a Hebrew dialect. Some people call it a Canaanite dialect or Amorite dialect.

The laws of Exodus and Deuteronomy are closest to those of Eshnunna, which is beyond the Tigris River. Why so far away? Nobody knows. Why are so many of the laws the same? Nobody knows.

HS: Give me an example of such a law.

AM: An ox that gores: You must kill him [Exodus 21:28–32]. In the Bible there are several passages about this. If the owner knew that it was a goring ox and the ox killed someone, then the owner, too, is to be killed. Why is this law in Eshnunna and not in the Code of Hammurabi [also from Mesopotamia and roughly contemporaneous]? Nobody knows. My idea is that Eshnunna was a Canaanite enclave.

But the Hammurabi Code also has a connection with Hebrew law. Landsberger used a German word for this—wandergut. It means that the law wandered. But there are many theories about the connections and the similarities.

HS: How does Mari fit into that?

046

AM: We have no laws from Mari. Just the language, with its similarity to Hebrew. I can list for you many words. For example, naveh. It is found only at Mari and in the Bible. It means “pasturage,” where nomads move around.

Many customs at Mari are the same as those in the Bible. For example, to solemnize a covenant at Mari you take the foal of an ass, and you cut it in two. You sacrifice it. And in the Bible, Abraham kills animals five different times when he makes a covenant. [for example, Genesis 15:7–11 and Genesis 22:13].

In Jeremiah, it is even closer. Jeremiah makes a covenant with the priests and cuts a young calf [to solemnize it; Jeremiah 34:13–16].

HS: What do you conclude from this kind of similarity?

AM: Mari is the best source for the protohistory of Israel. In its protohistory, Israel was a non-sedentary society, semi-nomadic like Mari. It is also a good source for the period of the Israelite Monarchy.

The name Abraham doesn’t appear at Mari, but the name Jacob is very often mentioned—at least 50 times, in all kinds of forms, like Jacob-el.

HS: Have you ever been to Mari?

AM: No, never. The former American ambassador to Israel, Thomas Pickering, asked me the same question. He was very interested in archaeology. He told me he was going to Mari. When I told him I had not been there, he said he would bring back photos and he did. The only thing you can see now is the throne room of the palace. At the end of his life Parrot campaigned for money to reconstruct Mari. But nothing happened.

HS: Thank you very much, Avraham.

A deep fissure runs through Biblical studies today. On one side are those who maintain that the Bible contains much reliable history; on the other side are those who say the Biblical texts were written much later than the events they describe and have little or no historical value. Some, like Israel Finkelstein, the co-excavator of Megiddo and the subject of an interview in our previous issue, portray themselves as centrists; Finkelstein thinks many key Biblical texts date to about the seventh century B.C. and he is dubious about texts that claim to report on earlier events. Another scholar […]

You have already read your free article for this month. Please join the BAS Library or become an All Access member of BAS to gain full access to this article and so much more.

Already a library member? Log in here.

Institution user? Log in with your IP address or Username