The Holy Sepulchre in History, Archaeology, and Tradition

034

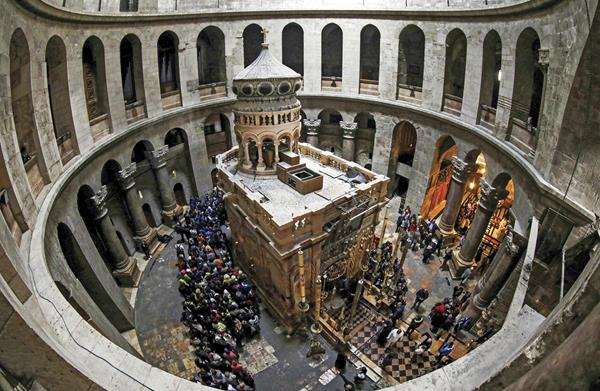

Few places on Earth excite as much imagination and religious fervor as the Church of the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem. This holiest Christian site has historically inspired both devotion and violence. Let’s briefly survey what modern archaeological investigation and ancient literary sources reveal about the architectural history of the Church of the Holy Sepulchre—from its establishment in the fourth century A.D. to its present form.1

The Church of the Holy Sepulchre sits embedded in the tightly packed streets of the northwestern section of Jerusalem’s Old City. Encased within its walls are the remains of a small piece of ancient Jerusalem, which, according to Christian tradition, was the site that witnessed the crucifixion, burial, and resurrection of Jesus Christ. For nearly 1,700 years, its doors have been thronged by Christian pilgrims seeking the Holy Tomb. Since the mid-19th century, the abundant historical data within the magnificent building has been the subject of scholarly interest. Archaeological investigation in particular has been ongoing in the church and its vicinity during the past six decades, most recently between 2016 and 2017. This research has illuminated the history of both the church and the site on which it was built.

035036

In the final centuries of Israel’s monarchy, the Northwestern Hill of Jerusalem, where the Church of the Holy Sepulchre and the present-day Christian Quarter are located, was partially taken up by a large stone quarry. The quarry descended toward the south and extended some 660 by 493 feet. Portions of it are still visible within the Church of the Holy Sepulchre and the buildings south of the church.

The old quarry probably originated in the ninth or eighth centuries B.C., which is evident from the pottery discovered in the earthen fills above the quarry bedrock within the Church of the Holy Sepulchre and its vicinity. It seems that the quarry was abandoned, at least partially, in the seventh century B.C., and the area settled with scattered suburbs. A rock-cut tomb dating to the eighth–sixth centuries B.C., found underneath one of the Holy Sepulchre’s many chapels, indicates that the quarry was also used for burials nearly a millennium before Jesus’s lifetime.

Archaeologists are not certain what became of the quarry in the years following the fall of Jerusalem to Babylon in the sixth century B.C., but it is likely that it was used in the Hellenistic period (332–66 B.C.) to furnish ashlars for the construction of buildings and defensive structures built by the Maccabeans, and also during the Early Roman period (63 B.C.–130 A.D.). Even the First and Second Walls of Jerusalem, as described by the Jewish historian Josephus in his Jewish War (5.142–146), could 037have been built with stone from this quarry.

During Jesus’s lifetime, the quarry continued to be used as a burial ground, evidenced by the presence of at least two first-century burial caves. From the Bible, we can also infer that the quarry had been turned into an execution site, locally called Golgotha, where criminals were killed in plain view of the people entering the city from the west. In keeping with Roman policy, Golgotha would have been located in an area that facilitated public visibility of those suffering capital punishment. In Jerusalem, the best place for such a site would have been the southernmost section of the old quarry nearest to the east–west road into the city.

The century following Jesus’s lifetime saw the spread of Christianity throughout the known world, as well as two major revolts by the Jewish inhabitants of Palestine against the Roman government, both of which triggered major cultural and physical changes in Jerusalem. The Second Jewish Revolt resulted in a significant reduction of the city’s Jewish population and the transformation of Jerusalem into a Roman city, in 130 A.D. Jerusalem was known for the next 200 years as Aelia Capitolina, named for the emperor in 130, Publius Aelius Hadrianus, who sponsored a number of public works to transform the city into a proper Roman civitas (city-state). This involved the construction of large paved roads in grid-like arrangements, public market places, and various shrines and temples.

At the site of the quarry on the Northwestern Hill of Jerusalem, archaeology has revealed only meager remains from the Late Roman period (130–324 A.D.). However, from the literary sources and the coinage of Aelia, we can safely conclude that Hadrian built a temple complex, probably devoted to Fortuna-Tyche, the goddess of fortune and luck, who was perhaps valued even among the city’s Christian inhabitants.2

In the fourth century A.D., the Roman Empire underwent significant cultural and political changes due in large part to the administration of Constantine I. Constantine had converted to Christianity early in his reign and, subsequently, legalized Christianity. Later, in 380 A.D., Theodosius I made it the official religion of the Roman Empire. As Christianity took on new life, 038interest in recovering sites and artifacts associated with Jesus’s life took hold among its adherents, particularly those in Jerusalem.

The move to recover the holy sites on the Northwestern Hill of Jerusalem likely began with a dialogue between Macarius, the bishop of Jerusalem, and Constantine during the Council of Nicaea (325 A.D.). The fourth-century church historian Eusebius wrote in his Life of Constantine that the emperor desired to unearth the tomb of Jesus and build a monument to the Savior’s resurrection (3.25), which would suggest that some background knowledge of the location of the tomb was provided to him by someone, probably Macarius. In Life of Constantine (3.29–32), Eusebius includes a letter written to Macarius by the emperor following the excavation of the tomb, which suggests an ongoing correspondence between the two. Still, the lack of any hard evidence—archaeological, literary, or otherwise—tying the emperor’s request to this particular site is speculative and is always the crux of the problem with any historical claim to the tomb of Jesus.

Interestingly, the circumstances indicate that Jerusalemite Christians had at least a general idea of where Jesus’s tomb was located. Eusebius’s Onomasticon (74.19–21), a study of toponyms in Palestine, shows that the location of Golgotha was well known in the fourth century. By extension, the location of Jesus’s tomb may very well have been known, and, because accessing the tomb meant tearing down the Hadrianic temple complex, Constantine’s involvement was necessary. Further, without the emperor’s financial backing and workforce, the project would not have been possible.

Constantine authorized the demolition of the old Roman temple, and excavation began. To everyone’s amazement, so says Eusebius, a rock-cut tomb was revealed (Life of Constantine 3.28). Constantine’s engineers disengaged the burial cave from the surrounding bedrock to single out the tomb for display in the church. The cave was adorned with columns and masonry, forming the first Edicule, the structure housing the tomb, which has stood in the Church of the Holy Sepulchre in various forms ever since.

Following the discovery of the tomb, construction began immediately on the church itself—a monument to the resurrection of Christ of such magnificence that it would rival the grandest structures of the empire. Thanks to the writings of Eusebius and other ancient authors, as well as the structure’s depiction on the highly stylized, sixth-century mosaic Madaba Map, we can reconstruct the original form of Constantine’s church (see sidebar).

The edifice proper, then called the Church of the Resurrection (Greek: ekklesia tou anastaseos), was oriented on an east–west axis with its entry on the eastern side, past the monumental gateway. Upon entering from the street, visitors 039would pass through a small courtyard and into the nave of the church, the basilica, from which they would descend into another, larger courtyard. Here they would find the Rock of Golgotha, a monolith from the old quarry, preserved due to its proximity to the tomb. This venerated limestone monolith is still visible within the church today. It is unlikely, however, that this monolith was used for the crucifixion due to its small size and surface area. It also has a large, natural fissure running through it (probably why it was left in the quarry) that would have made it unstable for human activity on its surface.

To the west of the Rock of Golgotha, stood the great cylindrical rotunda, called the Anastasis, or “Resurrection.” Upon entry into the rotunda, pilgrims would face the Edicule of the Tomb.

Byzantine Palestine in general, and Jerusalem in particular, withstood various incursions from the neighboring powers to the East, which resulted in damage to some of its prominent structures, including the Church of the Holy Sepulchre. With the advent of Islam in the seventh century A.D., Jerusalem surrendered to Muslim forces, who generally dealt peacefully with the Christian and Jewish inhabitants for several hundred years. Unfortunately, peaceful cohabitation did not last, as tension, particularly between Muslims and Christians, increased over time.

In 1009, Fatimid Caliph al-Hakim mandated the demolition of Jewish and Christian places of worship, marking one of the first dramatic expressions of hostility toward non-Muslims on the part of the Islamic authorities of Palestine. The Church of the Resurrection was almost completely destroyed—the basilica demolished, the upper and eastern portions of the rotunda torn down, and the Edicule nearly wiped out, except for portions of the north and south walls of the rock-cut tomb itself.

About a decade after ordering the destruction of Jerusalem’s churches and synagogues, Caliph al-Hakim’s policy toward Jews and Christians changed, and he allowed them to rebuild their houses of worship. The Church of the Holy Sepulchre was restored between 1020 and 1047 through the combined effort of three emperors. The restored church was much smaller than Constantine’s grand edifice, due to the fact that the basilica was not rebuilt. A new entrance to the church was added to the southern wall of the large courtyard housing the Rock of Golgotha, turning this space into the church’s nave. A subterranean chapel was established under where the basilica once stood in a section of the old quarry, where legend has it that Jesus’s cross was discovered. In the late fourth century, it was reported that the wood of the “true cross” was in the Church of the Holy Sepulchre (Socrates of Constantinople, Church History 1.17). This gave rise to the notion that the cross was discovered along with the tomb, but this is not supported in the historical sources.

Also in the 11th century, the Edicule was repaired, and the interior of the tomb chamber was covered in marble cladding to conceal the damage done by the agents of al-Hakim. In essence, these changes gave us the form of the church that we have today.

In the decades that followed the restoration, secular and ecclesiastical calls rang out for military assistance to liberate Palestine from Islamic 041rule. This resulted in a series of wars known collectively as the First Crusade. Armed Christian pilgrims and Frankish knights seized Jerusalem and captured the city in mid-July of 1099. They established a Christian kingdom with Jerusalem as its capital and the Church of the Holy Sepulchre at its heart.

The old Church of the Resurrection was the central focus of the Crusaders’ efforts, and they quickly set about turning the church back into a grand edifice. They undertook the task of bringing all the major components of the complex under one roof, creating a unified church focused on the holy tomb itself, and they called it the Church of the Holy Sepulchre (Latin: Ecclesia Sancti Sepulchri).

The Crusaders followed the general plan established during the repairs of the 11th century but made a few modifications. They beautified the façade of the church’s entryway, and they added the bell tower that abuts the building on the northwest corner of the entry pavilion to this day. (The present bell tower is much smaller than its original height of five stories.) Inside the church, the Rock of Golgotha was incorporated into the church proper with the establishment of a two-story chapel, made up of the Chapel of Adam on the ground level and Calvary above. They also established the semicircular ambulatory to the east of the central choir area, from which visitors could access three small, semicircular chapels.

The Church of the Holy Sepulchre, as it stands today, has changed very little since the 1160s, when the Crusaders completed their work. With the exception of a few modifications added largely to meet modern safety standards, the only major changes in the church since the 12th century have focused on the Edicule of the Tomb. Fortunately, because of the importance of the structure, the work done on it has largely been documented, which has provided valuable archaeological data.

The Edicule, as we have seen, has stood within the Church of the Holy Sepulchre in one 042form or another since the church was established in the fourth century. The original Edicule consisted mainly of the rock-cut tomb and various embellishments, and in the 11th century it was supplemented with marble cladding. The decaying Edicule was rebuilt in 1555, this time as a small building that completely enclosed the burial cave.

Due to damage sustained during a fire within the church in 1808, the Edicule was rebuilt again between 1809 and 1810, giving the monument its present form. This magnificent Edicule was damaged during an earthquake in 1927 and was strapped together with steel girders by the Public Works Department of the British Mandate of Palestine to keep it from falling apart. It sat in this state for nearly a century, until its restoration in 2016.

Before discussing the most recent restoration of the Edicule, it is important to say a few words about the appearance of the sacred burial cave itself during the earlier restorative efforts. The limestone bedrock of the tomb chamber was probably visible to the public in Constantine’s church, but it was covered by marble in the 11th century. The burial bench was covered in marble earlier, likely in the fourth century, perhaps to keep people from chipping away at the stone to procure relics. During the 2016 restoration, workers discovered a marble covering with an incised cross under the current marble cladding of the burial bench. The mortar between the limestone bedrock of the burial bench and the marble dated to the fourth century A.D., thereby showing that the burial bench had been covered soon after the church’s initial construction.3

We know from extant documentation that those involved in the restoration of the Edicule in 1555 were thrilled to see the actual tomb when they removed the marble cladding. During the second rebuilding of the Edicule in 1809, when the medieval structure was dismantled, a local monk named Maximos Simaios described the tomb’s remains as consisting of two sections, one on the north and one to the south, with the northern section retaining a portion of the burial bench.

In 2016, a conservation team from the National Technical University of Athens (NTUA) undertook the task of restoring the Edicule in cooperation with the National Geographic Society. Under the leadership of Antonia 043Moropoulou, the team dismantled and then rebuilt the Edicule using the existing marble cladding—but securing its pieces with titanium rods. The rock-cut tomb, as revealed by NTUA, was generally consistent with the account from 1809: a northern wall, standing about 4 feet tall, with a portion of what appears to be the burial bench extending a little more than 3 feet from the lower half of the upright portion, giving the wall an L-shape when viewed in section; and a southern wall standing about 5 feet tall and located a little more than 3 feet from the burial bench of the northern wall. Archaeological investigation of the remains within the Edicule revealed masonry and marble layers consistent with fourth- and 11th-century construction.

The conservators from NTUA reported that the Church of the Holy Sepulchre still needs significant work not only to preserve the structure as a whole, but also to make it safe for the thousands of visitors who traverse its halls every day. As is often the case, future repair work and conservation will continue to shed light on the archaeology of this immensely complicated and fascinating structure. Like the city of Jerusalem, in which it is situated, the Church of the Holy Sepulchre continually offers something new and interesting to inspire the meditation of countless pilgrims and fill volumes of academic texts.

For those who love the Church of the Holy Sepulchre, regardless of their persuasion on the matters of Jesus’s death and resurrection, there awaits an intriguing study of history, text, tradition, architecture, archaeology, and, not least of all, faith.

The Church of the Holy Sepulchre is revered as the site of Jesus’s death, burial, and resurrection. BAR readers get a look at the church’s history and tradition in light of new archaeological research.

You have already read your free article for this month. Please join the BAS Library or become an All Access member of BAS to gain full access to this article and so much more.

Already a library member? Log in here.

Institution user? Log in with your IP address or Username

Endnotes

1.

This article is based on the fourth chapter of Justin L. Kelley, The Church of the Holy Sepulchre in Text and Archaeology: A Survey and Analysis of Past Excavations and Recent Archaeological Research with a Collection of Principal Historical Sources (Oxford: Archaeopress, 2019), pp. 65–126.