The Infancy Narratives in Matthew and Luke—Of History, Theology and Literature

A review article of Raymond E. Brown’s monumental The Birth of the Messiah

046

Jesus’ birth and infancy are described in the Gospels of Matthew and Luke, but are not even mentioned in Mark and John.

Moreover, the infancy narratives in Matthew and Luke are seemingly quite different from one another. Luke mentions the census of Quirinius which requires Joseph to go to Bethlehem where Jesus is born in a manger because there is no room at the inn. Matthew, however, gives no details of how Joseph and Mary came to be in Bethlehem; nor are there any details of Jesus’ birth.

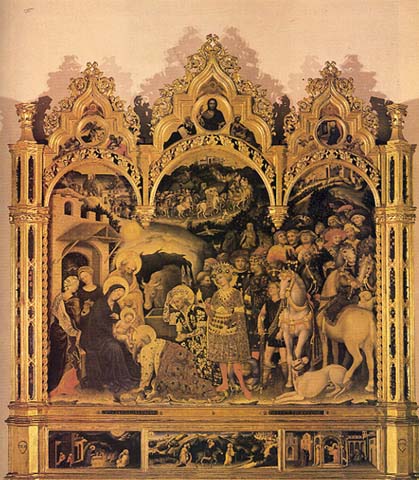

In Luke, shepherds guided by an angel find Jesus in the manger; they praise God for what they have seen but do not bring the child gifts. In Matthew, wise men from the East, guided by a star, come not to Bethlehem but to Jerusalem to worship the Infant. Herod hears of the wise men from the East and sends them to Bethlehem to learn and report to him about the Infant. The wise men unlike the shepherds in Luke bring the Infant gifts of gold, frankincense and myrrh, but, warned by an angel, return to their own country instead of reporting to Herod. Warned by an angel that Herod intends to kill the child, Joseph flees with his wife and child to Egypt where they live until Herod’s death; then they return to Nazareth instead of Bethlehem.

Luke, on the other hand, does not mention the descent into Egypt. Instead, he describes how the Infant is brought to Jerusalem for the ritual of the first-born. In Jerusalem, Joseph offers a traditional sacrifice at the Temple; then Joseph, Mary and the child return to live again in Nazareth.

These are some of the differences between the only two Canonical Gospels which describe Jesus’ birth and infancy. They are not necessarily contradictory, but they are different from one another.

Strangely enough, Paul provides no information whatever about Jesus’ birth, although he mentions it in three letters (Romans 1:3, Galatians 4:4, 7, Timothy 2:8).

The birth and infancy materials in Luke and Matthew have been approached quite differently by various 049scholars. More conservative scholars tend to regard the Infancy Narratives as largely accurate historical reports; the differences between the accounts are resolved on a variety of historical grounds. Less conservative scholars, on the other hand, tend to regard the Infancy Narratives as creative, literary products; the differences among the narratives are accounted for on literary and theological grounds.

Until now, however, there has been no major modern commentary which focuses exclusively on the Infancy Narratives. In The Birth of the Messiah, Raymond E. Brown seeks to fill this gap. Brown is probably the ideal person to undertake the job. In the world of Biblical scholarship, his name is a household word. Time magazine called him, “probably the premier Catholic scriptural scholar in the U.S.” He is highly esteemed in Protestant as well as Roman Catholic circles, and his scholarly credentials are impeccable. Brown was co-editor of the prestigious Jerome Biblical Commentary, and editor of two books of dialogue between Protestant and Roman Catholic scholars: Mary in the New Testament and Peter in the New Testament Among his many books is the epic two-volume commentary on John in the Anchor Bible series, undoubtedly the leading modern commentary on John’s Gospel. He has served as president of both the Catholic Biblical Association and the Society of Biblical Literature. He is active in ecumenical affairs, having been the only American Catholic on the Faith and Order Commission of the World Council of Churches, and having served as consultant to the Vatican Secretariat for Christian Unity.

Brown agrees with the present consensus of less conservative Biblical scholarship that the Infancy Narratives were created by the early Christian community primarily to express its theology. According to this hypothesis, the central element in the earliest Christian Kergymaa was the Holy Spirit’s “designating” Jesus as the Son of God in association with his resurrection; (Romans 1:4). As the Christian community reflected on Jesus as the Son of God—so designated by the Holy Spirit—this designation was projected back into Jesus’ life (rather than merely at his resurrection), especially to the event which inaugurated Jesus’ public ministry, his baptism.1 Thus, according to this hypothesis, at a later stage in the development of Christian understanding, the Holy Spirit descended upon Jesus and he was designated and proclaimed as God’s Son at his baptism (See Mark 1:10–11)2

The next stage in this hypothesized theological development projected the Christological Kergyma back to Jesus’ conception and birth. This is the Christology reflected in the Infancy Narratives of Matthew and Luke, where the Holy Spirit and Jesus’ designation as “Son of God” are conjoined at Jesus’ conception and birth.

Accordingly, for Brown the Infancy Narratives in Matthew and Luke are the literary distillation of this hypothetical process by which the kergyma about Jesus as Son of God through the power of the Holy Spirit was related to Jesus’ birth.

With this hypothetical, theological foundation in place, Brown then analyzes the literary and historical aspects of each of the two Gospel accounts.

In a well-developed and strongly supported presentation, Brown concludes that the individual authors of Matthew and Luke3 were responsible for the final literary form of their respective Infancy Narratives. Each reflects its own consistent style, language, concerns, and theological perspective. To account for the similarities between the two Infancy Narratives, Brown hypothesizes that both authors made use of a pre-Gospel annunciation tradition that was circulating at the time they wrote. In agreement with an almost unanimous scholarly consensus, however, Brown concludes that the Infancy Narratives are nevertheless entirely independent of one another; that is, neither author made use of the other in writing his own account.

Brown divides Matthew into four sections which he labels “Who” (1:1–11), “How” (1:18–25), “Where” (2:1–12), and “Whence” (2:13–23).4

In the “Who” section (Matthew 1:1–11), Matthew sets forth Jesus’ genealogy as “the Son of David, the Son of Abraham.” According to Brown, Matthew utilized two genealogical lists which were available to him from early Jewish-Christian tradition. The first was a pre-monarchical genealogical list from Abraham to David with which Matthew and Luke’s genealogies are in almost complete agreement. This pre-monarchical genealogy was derived from Old Testament genealogies.b The second source was a monarchical and post-monarchical genealogical list from David to Jesus which derived both from the Old 050Testament and popular tradition about the Davidic lineage. To this list, Brown suggests, Matthew simply added the names of Joseph and Jesus. Brown theorizes that Luke may have utilized a family genealogy of Joseph instead of the post-monarchical genealogy used by Matthew.

This would account for the complete difference between Luke and Matthew on Jesus’ post-Davidic lineage. For both Matthew and Luke, however, the central issue in the genealogies, according to Brown, is not history, but an evaluation of who Jesus was.

At certain points in Matthew’s genealogy, he includes mothers was well as fathers—Tamar, Rahab, Ruth, and the wife of Uriah (Bathsheba). Brown suggests the reason is that each of these women was involved in an extraordinary or irregular marital union in which the woman played an instrumental role in God’s plans. They thus became forerunners of Mary. In addition, each of these women had a Gentile heritage or association which foreshadows the inclusion of Gentiles in God’s salvation through Jesus.

Thus, by his genealogy Matthew (1) presents Jesus the Messiah (1:1, 16, 17) as the Son of David and the Son of Abraham, the fulfillment of Jewish messianic expectations; (2) prepares for the unusual nature of Jesus’ birth by the inclusion of women in the genealogy; and (3) begins to establish the salvation of the Gentiles (a promise to Abraham—see Genesis 12:2–3; 22:17–18) through linking Jesus back to Abraham and including the Gentile elements in the genealogy.

In the “How” section (1:18–25), Brown suggests, Matthew first shows how Jesus became Son of David through Joseph the Davidid: Joseph obeys the angelic command to take Mary as his wife and, implicitly, takes responsibility for the “legal paternity” of her son by naming him (“Joseph, son of David … you shall call his name Jesus,” 1:20–21).

Thus Matthew designates Jesus as the Son of David even though Jesus’ conception was by the Holy Spirit. Jesus’ Davidic heritage was apparently part of the earliest Christian traditions. Even Paul, who carefully noted his own lineage (Romans 11:1, Philippians 3:5), accepted a pre-Pauline tradition concerning Jesus’ Davidic heritage (Romans 1:3).

Contrary to those scholars who hold Jesus’ Davidic heritage to be a theological creation of the early Jewish-Christian community, Brown suggests that Jesus’ Davidic descent is one of the few historically accurate facts in the Infancy Narratives, although it too has been theologically developed.

Matthew’s second purpose in the “How” section is to show how Jesus is the Son of God. Brown assumes that Matthew combined an early kergymatic proclamation of Jesus as the Son of God through the Holy Spirit, with a tradition involving an angelic annunciation of the birth of the Davidic Messiah. After describing and analyzing the literary form of such messianic annunciations, Brown suggests that, in a pre-Matthean development, the kergymatic proclamation of Jesus as God’s Son may have been incorporated into an annunciation of the birth of the Davidic Messiah. The final passage in the “How” section (1:22–25) contains the formulaic citation of an Old Testament passage, Isaiah 7:14:

“All this took place to fulfill what the Lord had spoken by the prophet:

‘Behold, a virgin shall conceive and bear a son, and his name shall be called Emmanuel’.”

The formulaic citation of the fulfillment of Old Testament prophecies is a characteristic feature of Matthew’s Gospel. Brown correctly notes that Matthew’s citation of Isaiah 7:14 adds Biblical testimony to the angelic revelation that Jesus is “God with us,” and has no direct bearing upon the nature of Jesus’ conception.

According to Brown, it is the subsequent verse, Matthew 1:25 (Joseph “knew her not until she had borne a son”), that relates to the nature of Jesus’ conception; this was added by Matthew to let his readers know that even though Joseph obeyed the angelic revelation and took Mary as his wife, the virgin state of Mary introduced in 1:18 was maintained until after Jesus’ birth.

Thus, according to Brown’s theory in the “How” section, Matthew utilized an existing narrative of the annunciation of the birth of the Davidic Messiah into which the Christian proclamation of Jesus as God’s Son through the Holy Spirit was incorporated. Into this, Matthew wove a portion of the narrative containing angelic dream appearances to Joseph. To this reworked 052combination of traditions, Matthew then added the citation of Isaiah 7:14, and the concluding verses (1:24–25). Brown recognizes that the Matthean reshaping of this material is so complete that any exact reconstruction of the pre-Matthean narratives is impossible.

While Brown does not argue for the historicity of 1:18–25, he maintains there was a historical catalyst behind Matthew’s (and Luke’s) portrayal of the unusual circumstances of Mary and Joseph’s relationship with respect to Jesus’ conception; that is, Matthew and Luke’s retention of the fact that Mary’s pregnancy preceded the consummation of her betrothal to Joseph. It is highly improbable, Brown suggests, that the Christian community would, without historical basis, create an account which would leave Jesus’ birth open to the charge of illegitimacy, a charge which subsequently arose among Christianity’s opponents.

Matthew 2 contains the “Where” and the “Whence” sections of the Infancy Narrative. Brown describes it as a drama in two acts.

The “Where” section (2:1–12) contains two scenes: 2:1–6 and 2:7–12. The “Whence” section (2:13–23) contains three scenes: 2:13–15, 2:16–18, and 2:19–23. Each of these five scenes concludes with a typically Matthean formulaic Old Testament citation, either explicit or implicit. According to Brown, this repeated structure clearly indicates that Matthew, a single individual, is responsible for the final literary form of this segment of the Infancy Narrative.

The two acts and five scenes may be summarized as follows:

Act I: Where

Scene 1 (2:1–6): Jesus is born in Bethlehem in the days of Herod. Wise men from the East come to Jerusalem looking for the child who is to be king of the Jews. Herod is troubled. The chief priests and scribes confirm the views of the wise men, quoting Old Testament prophecy (Micah 5:2):

“But you, O Bethlehem, in the Land of Judah, are by no means least among the rulers of Judah; for from you shall come a ruler who will govern my people Israel.”

Scene 2 (2:7–12): Herod sends the wise men to Bethlehem to search for the child. They follow the star to find the child and his mother. They bring him gifts and worship him, but, instead of reporting to Herod, they return to their own country.

The reader is implicitly reminded of Psalm 72:10–11 (“The kings of Tarshish and of the islands render him tribute, the kings of Sheba and Seba bring gifts, and all kings fall down before him … ”) and Isaiah 60:6 (“ … those from Sheba … shall bring gold and frankincense, and shall proclaim the praise of the Lord”).

In the first act, Brown suggests, Matthew utilized a pre-Matthean narrative of Jesus’ birth. This narrative had been modeled upon Old Testament accounts of the infancy of Moses and Moses in Egypt as they had been developed in Jewish midrashic5 traditions and adapted by the early Jewish-Christian community to Jesus’ infancy. All this was then brought together in the narrative of the 053angelic dream appearances to Joseph. To this pre-Matthean narrative, Brown proposes that Matthew joined another pre-Matthean narrative: the account of the Magi which had been modeled upon the Balaam story in Numbers 22–24, especially 24:17 (the star from Jacob), as it had been developed in Jewish messianic expectations. Brown notes that in the account of the first century Jewish philosopher Philo, Balaam is called a magus (plural—magoi), who is accompanied by two servants (thus a party of three). This trio foils the hostile plans of King Balak against God’s people, just as the Magi in Matthew foiled King Herod’s plans.

Brown also sees here another aspect of the Moses pattern, again taken from Philo: Philo reports that advisors informed Pharaoh about the birth of Moses; they too are called magoi. Thus, according to Brown, the Moses model and the Balaam model have been conjoined at this point in the Infancy Narrative.

Brown identifies two principal themes in Act I of the Matthean narrative. The first is the Jewish rejection of Jesus in the actions of Herod in association with the chief priests and scribes.6 This will become a central theme throughout Matthew’s Gospel. The second theme in Act I is the intimation of the Gentiles’ belief in Jesus as represented by the homage and gifts of the Magi.

Other than the fact of Herod’s kingship and a dubious possibility of birth at Bethlehem, Brown finds no historical basis for this portion of the Narrative.

Act II of Matthew’s Infancy drama is the “Whence” act. It consists of these scenes:

Scene I (2:13–15): An angel tells Joseph in a dream to take the mother and child to Egypt to avoid Herod. So Joseph takes the infant Jesus to Egypt, leaving by night and staying until Herod’s death. “This was to fulfill what the Lord had spoken by the prophet, ‘Out of Egypt have I called my son”’ (See Hosea 11:1).

This, Brown tells us, is modeled on Moses’ escape as an infant from Pharaoh, as well as Moses’ adult flight to Midian, again to escape Pharaoh’s wrath. Thus Jesus was likened to Moses, the giver of the Old Covenant, and equated with Israel, the called-out people of God.

Scene 2 (2:16–18): Herod slays all male children in Bethlehem under two years of age. The scene ends with a formulaic citation to Old Testament prophecy:

“Then was fulfilled what was spoken by the prophet Jeremiah, ‘A voice was heard in Ramah, wailing and loud lamentation, Rachel weeping for her children; … because they were no more’.” (Jeremiah 31:15).

This, Brown tells us, was patterned upon Moses’ escape from the slaughter of the male infants in Egypt. In addition, Brown contends that Matthew’s citation of Jeremiah 31:15, links Jesus to another great event in the history of Israel—the Exile. Thus three of Matthew’s Old Testament citations mention Egypt (the place of the Exodus), Bethlehem (the City of David), and Ramah (the mourning place of the Exile).

Scene 3 (2:19–23): Pursuant to angelic direction revealed in a dream after Herod’s death, Joseph returns 056with his family to Israel. Still afraid, however, and warned in a dream of Herod’s successor, Joseph goes to live in Nazareth, in order that “what was spoken by the prophets might be fulfilled: ‘He shall be called a Nazarene.”’ (Isaiah 11:1 contains the Hebrew word Ne

µ zer [branch], similar to Nazareth, which is probably one of the intended references here. In this passage, Isaiah announces the coming of a new king of the Davidic line.)

Brown finds almost no historical basis for the events described in Act II, other than the fact that Herod was the ruler of Judea and was succeeded by his son Archelaus. However, he does note that the massacre of the infants of Bethlehem is consistent with Herodian practices. The flight to Egypt, the massacre of the infants, the return to Israel are, for Brown, simply literary fictions designed to present Matthew’s theological understanding of Jesus.

As Brown perceives it, Matthew’s Infancy Narrative is a thoroughly Matthean literary construction which he created by reworking and merging pre-Gospel narratives and genealogies and adding formulaic citations from the Old Testament. Matthew’s purpose was to present the Gospel in miniature, thus making the Infancy Narrative a literary vehicle for Christology. Whatever historical elements might be present in the Infancy Narrative are of a completely secondary nature and inconsequential in the literary development of theological themes.

Turning to Luke’s Infancy Narrative, Brown acknowledges that the Lukan redaction7 is so skilled and complete that the delineation of pre-Lukan material is more difficult than in Matthew. For Brown, the present Lukan Narrative is the result of a two-stage literary development. In the first stage Luke created two diptychs or parallel accounts: one containing the annunciation accounts for John and Jesus (1:5–25 and 1:26–45, 56); the other, the birth-circumcision-naming accounts for John and Jesus (1:57–66, 80 and 2:1–12, 15–27, 34–40). To this nicely balanced, finished literary creation Luke later inserted four pre-Lukan canticles: the Magnificat (1:46–55), the Benedictus (1:67–79), the Gloria (2:13–14), and the Nunc Dimittis (2:28–33). Brown suggests these were hymnic compositions of the Jewish-Christian Anawim8 of Jerusalem. Also at this second stage Luke added the pre-Lukan account of the boy Jesus in the Temple, astounding the elders with his understanding (2:41–52). Brown suggests that the Temple scene had its origin in the popular tradition of preministry marvels, attested in John 2:1–11, and in the apocryphal Gospels.9

The Annunciation Diptych (1:5–56). Brown proposes that Luke created the annunciation of John’s birth (1:5–25) on the pattern of the annunciation of Jesus’ birth (1:26–56). The only possible historical elements, according to Brown, are the dating of the event in the reign of Herod the Great and perhaps the names and priestly lineage of John’s parents. Luke modeled Elizabeth and Zechariah on two famous Old Testament accounts of births to barren couples: Elkanah-Hannah in Samuel’s birth (1 Samuel 1–2), and Abraham-Sarah in Isaac’s birth (Genesis 17–18). Brown’s thesis is that Luke utilized the theme of barrenness and the Old Testament annunciation pattern as a bridge of continuity between the history of Israel and the history of Jesus’ life and ministry.

According to Brown, in the Jesus half of the Annunciation Diptych (1:26–56), Luke reworked the same pre-Gospel annunciation of Jesus’ birth as the Davidic Messiah used by Matthew (“He will be great, and will be called Son of the Most High; and the Lord God will give to him the throne of his father David, and he will reign over the house of Jacob forever; and there will be no end to his kingdom” [1:32–33]). Like Matthew, Luke also added the kergymatic proclamation of Jesus’ divine sonship through the Holy Spirit (“The Holy Spirit will come upon you, and the power of the Most High will overshadow you; therefore the child to be born will be called Holy, the Son of God” [1:35]).

As we have seen, Brown maintains the need for a historical catalyst behind the tradition of a virginal conception. But Luke’s account of the virginal 057conception, according to Brown, is a literary device to join together these two pre-Gospel traditions about the birth and nature of Jesus.

At a later stage, Brown hypothesizes, Luke added to this half of the diptych the Magnificat (1:46–55) which he puts in the mouth of Mary, but which he received from the Jewish-Christian Anawim of Jerusalem. Luke inserted in the Magnificat its future orientation (Henceforth all generations will call me blessed” [1:48]) because as originally written the canticle praised God for an accomplished, not a future, salvation.

The Birth-Circumcision-Naming Diptych (1:57–2:40). The first half of the second diptych describes the birth, circumcision, and naming of John and originally closed with a summary statement of his growth (1:80), which included two elements taken from the synoptic ministry of John: “strong in Spirit” and “in the desert.”

Again, to this completed portion of the diptych, Luke later added the Benedictus (1:67–79): “Blessed be the Lord God of Israel … ”) which he puts in the mouth of Zechariah but which he received from the Jewish-Christian Anawim of Jerusalem. Luke amended this canticle of praise, however, by adding 1:76–77 (“And you, child, will be called the Prophet of the Most High; for you will go before the Lord to prepare his ways … ”) to give a future reference to what was originally praise of God’s accomplished salvation. This addition also related John to the Old Testament forerunner of the Lord (= Messiah), referred to in Isaiah 40:3 and Malachi 3:1.

As we shall see, the Jesus section of the Birth-Circumcision-Naming diptych (2:1–21) is more complex than the John portion. To it, Luke has added a Temple scene (2:22–39) built around two Jewish practices: the consecration of the first-born, and the purification after birth.

Brown proposes that the census described in Luke 2:1–5 is a Lukan device without historic basis. Brown suggests that Luke, having a tradition that the birth of Jesus was associated with the end of a Herodian rule, confused Herod the Great (who died in 4 B.C.) with his son Archelaus (who was deposed in 6 A.D.). There was a census taken in 6 A.D., and Luke utilized an idealized form of this census as a means of bringing Mary and Joseph to Bethlehem.

Brown interprets the angel appearing to the shepherds to announce Jesus’ birth as a typical annunciation form in which Luke utilized (1) Isaiah 9:6 (describing a newborn child who is to be heir to the throne of David), and (2) Isaiah 52:7 (describing the messengers who bring the good news of salvation). Thus the angels, in fulfillment of Old Testament prophesy, announce the Christian Kergyma of a Savior, Messiah, and Lord. Luke also employs the shepherds as forerunners of future Christian believers who will come to Jesus, see, and rejoice and praise God. At a later stage, Luke added a brief Jewish-Christian canticle, the Gloria (2:13–14). This he puts in the mouth of an angel of the Lord.

Brown turns next to the Temple scene shortly after Jesus’ birth (2:22–39). Brown believes that Luke constructed this scene, using as a model Malachi 3:1 (“The Lord whom you seek will suddenly come to his Temple”) and Daniel 9:24 (which speaks of anointing a most Holy One, understood, by Luke, to be Jesus). According to Brown, at a later stage in the development of this narrative, Luke added the Nunc Dimittis (2:29–32), utilizing another Jewish-Christian canticle. While the angelic annunciation to the shepherds would meet the expectations of Israel, the Nunc Dimittis reaches out to the Gentiles: “Lord … mine eyes have seen thy salvation … a light for revelation to the Gentiles.”

The second diptych in Luke originally closed with a description of Jesus’ youth in Nazareth (2:39–40) as a transition to his later ministry (3:21).

Brown tells us Luke added the account of the boy Jesus in the Jerusalem Temple (2:41–52) to his diptychs at the 058same time he added the Magnificat, Benedictus, Gloria, and Nunc Dimittis. Jesus at age 12 in the Temple for Passover, astounds the Jewish elders with his understanding; but his parents don’t understand when Jesus tells them he must be in his Father’s house. Brown theorizes that Jesus’ parents don’t understand because they do not yet have the post-resurrection faith in Jesus as God’s Son which enabled Luke to insert this account to show the continuity from the infant Jesus through the boy Jesus in the Temple to the resurrected Lord.

Thus, according to Brown, Luke’s Infancy Narrative involves two stages of literary creation: (1) the development of two diptychs; one containing parallel annunciations of the births of John and Jesus, the other presenting parallel accounts of the Birth-Circumcision-Naming of John and Jesus; (2) the later addition, by Luke, of two different sets of materials he received from tradition: four canticles from the Jewish-Christian Anawim of Jerusalem, and a popular tradition of pre-ministry marvels of Jesus which was the basis of the twelve-year-old boy astounding the Temple elders. This was Luke’s method of creating a literary vehicle for presenting the Christology of the Christian movement. Luke takes the Kergyma about Jesus (in which Jesus is “designated Son of God in power according to the Spirit of holiness” [Romans 1:4]), which was originally applied to the resurrection, and applies it to the birth of Jesus.

Despite frequent assertions which seem to suggest that much of the Matthean and Lukan Infancy Narratives contain historically accurate facts, Brown is nevertheless an extreme minimalist with respect to the historicity of the Infancy Narratives. At most, Brown accepts the placing of Jesus’ birth in the last days of Herod the Great’s reign, acknowledges that there must have been some “historical catalyst” behind the accounts of the unusual nature of Jesus’ conception, accepts Jesus’ Davidic descent, presumes the possible historicity of the names and priestly lineage of John’s parents, suspects that Anna might have been a historical figure of the Jewish-Christian Anawim in Jerusalem, holds to the birth in Bethlehem although with reservations, and accepts Nazareth as the place of Jesus’ home and the place from which he began his ministry.

Historical fact, however, is unimportant to Brown’s perspective of the Infancy Narratives. For Brown, the Infancy Narratives are not concerned with history. Whatever historical facts they contain are, for the most part, incidental and inconsequential. The Infancy Narratives succeed not as history, but as powerful literary presentations of a theological perspective. This, not history, is their purpose.

Brown and other Biblical scholars are certainly correct in concluding that the post-resurrection faith of the Christian community was read back into the early life of Jesus. But, in this reviewer’s judgment, these scholars, including Brown, over-extend their theory when they assume that this theological “reading back” necessarily resulted in the creation of stories about Jesus designed to substantiate the post-resurrection faith and apply it to an earlier stage of Jesus’ life. To be sure, the “creation” of such stories did take place as we know from the apocryphal gospels and apocryphal infancy narratives. These apocryphal materials build on the canonical gospels in a highly imaginative and fictitious way, but this does not necessarily mean that the canonical Gospels are creations of the same order.

The Gospels recount numerous instances in which the disciples are mistaken in their perception and understanding of who Jesus was. The disciples fail to understand who Jesus is (see Matthew 20:22, Mark 4:41, Luke 3:23 [the suppositions about Jesus’ lineage], John 14:5, 9). The disciples fail to understand Jesus’ actions (see Mark 6:52, 8:17–21). The disciples fail to understand Jesus’ teachings (see Matthew 15:16, 16:9–11, Mark 4:13, Luke 24:25 [understanding comes through the resurrected Jesus], John 10:6). The disciples fail to understand Jesus’ death (see Mark 8:32, 9:32, Luke 18:34). Even Jesus’ family expresses concern, dismay, and sometimes disbelief (see Mark 3:21, John 7:5), and John the Baptist sends to inquire whether 059Jesus was indeed “the coming one,” (see Matthew 11:2). In the Lukan Infancy Narrative, Mary ponders Gabriel’s annunciation (1:29) and the shepherds’ announcement (2:19), and Mary and Joseph fail to comprehend Jesus’ statement of his commitment to his Father (2:49–50).

All of this reflects partial, limited, inadequate perceptions about Jesus during his earthly life and ministry. Would it not be logical then for the Christian community, in the light of its post-resurrection faith, not to “create stories about Jesus, but to “correct” or “interpret” the historical life of Jesus?10 Brown seems to be dimly aware of this possibility in his analysis of the scene about the boy Jesus in the Temple, but as a whole it is never taken into consideration. As theological “correction,” rather than “creation,” the Infancy Narratives might then retain a much higher degree of historicity than Brown would attribute to them.

Brown and other Biblical scholars are assuredly correct in their contention that the Infancy Narratives are the literary expression of the Christian community’s theological reflection upon Jesus’ early life. They are also correct in noting that this theological reflection was set in then-current, acceptable literary forms. But the use of common literary forms does not automatically prejudge the historicity of the material found in those forms, even if other uses of the forms (such as the apocryphal gospels) are purely fictitious. The use of literary forms does not necessarily require the abandonment of historical fact. The historical facts themselves may well have given rise to the use of then-current Old Testament midrashim and Jewish messianic expectations as vehicles of illumination and insight into those facts. But the use of such forms does not force us to conclude that they are merely fictitious vehicles for the conveyance of theological perspectives with minimal regard for historical facts. The literary forms utilized by the writers of the Infancy Narratives may be means to convey and enhance the theological understanding of historical events.

Brown and other Biblical scholars are correct in recognizing the historical difficulties within and between the Infancy Narratives, especially when they are evaluated by the standards of modern critical perceptions of history. Undoubtedly unresolved historical questions regarding the Infancy Narratives will continue to vex us: However the more conservative attempt to resolve all historical problems and the less conservative attempt to deny most or all historicity to the Infancy Narratives because of these historical problems, are both inadequate extremes. A sounder critical and scholarly conclusion is to hold in dynamic tension the implicit historicity of the Infancy Narratives and their unresolved anomalies. Thus, while neither expecting nor requiring complete historical accuracy (this is not possible even with respect to modern history, despite the amount of material available), we may assume a reliable historical matrix constituting the essential warp and woof of the Infancy Narratives. This historical matrix, in which there was doubt, uncertainty, and misunderstanding about who Jesus was, is subsequently developed in the fullness of the post-resurrection experience. Then, the Christian community, guided by the indwelling Holy Spirit, could correct and complete the partial and confused understandings of Jesus. This was accomplished through standard literary forms and the employment of Jewish-Christian hymns, as well as utilizing Jewish and Christian midrashic exegesis of the Old Testament. While the post-resurrection experience was crucial and central in understanding the birth and infancy of Jesus, the object of understanding was historical and the method of conveying understanding was literary.

Jesus’ birth and infancy are described in the Gospels of Matthew and Luke, but are not even mentioned in Mark and John.

You have already read your free article for this month. Please join the BAS Library or become an All Access member of BAS to gain full access to this article and so much more.

Already a library member? Log in here.

Institution user? Log in with your IP address or Username

Footnotes

Kergyma is the Greek term for “proclamation.” In Biblical scholarship it is a technical term for the content of the Christian proclamation about Jesus.

This genealogy probably contained 14 generations. In Hebrew each letter has a numerical value. The numerical value of David (DVD) is 14. Brown hypothesizes Matthew picked up and developed this idea so that in his genealogy of Jesus, there are 14 generations from Abraham to David, 14 generations from David to the Babylonian Exile, and 14 generations from the Babylonian exile to Jesus (Matthew 1:17). In this way Matthew tied his whole genealogy together.

Endnotes

Some scholars see the transfiguration of Jesus (Mark 9:2–13) as a stage in the transition between the resurrection and the baptism.

This hypothetical stage is still retained in Matthew (3:16–17) and Luke (3:22), although they both, as shall be seen, carry the Christological kergyma back to Jesus’ conception. This stage is also reflected in John (1:32–34) although John carries the Christological kergyma back to the pre-existence of the Son of God.

Brown does not deal with the questions of authorship but uses “Matthew” and “Luke” to designate the person responsible for the final form of each Gospel.

In these categories Brown adopts A. Paul’s L’Evangile de l’Enfance selon saint Matthieu, Paris, 1968 doubling of Stendahl’s Quis et Unde (Judentum, Urchristentum, Kirche, Berlin, 1964).

Brown utilizes the definition of A. Wright, The Literary Genre Midrash, New York, 1967: “A midrash is a work that attempts to make a text of Scripture understandable, useful, and relevant for a later generation. It is the text of Scripture which is the point of departure, and it is for the sake of the text that the midrash exists. The treatment of any given text may be creative or non-creative, but the literature as a whole is predominantly creative in its handling of biblical material. The interpretation is accomplished sometimes by rewriting the biblical material.” (p. 74)

The scribes being the basic opponents of Jesus during his ministry, and, together with the Chief Priests, responsible for his crucifixion.

Redaction is the literary activity by which an individual takes material already available to him, organizes it in his own way and reworks it as well as adds to it to create his own literary product.

“Anawim” is a Hebrew term meaning “poor,” “humble,” or “afflicted.” As Brown notes, it came to mean those who, because of their condition, could not rely upon their own strength but had to rely completely upon God. Brown states, “ … under the catalyst of defeat and persecution (during the post-exilic period, 538–167 B.C.), the remnant was redefined, not in historical or tribal terms, but in terms of piety and way of life.” (351) It is Brown’s excellent hypothesis that certain of the Jewish Anawim became converts to Christianity and composed their own Jewish-Christian canticles of praise for God’s salvation in Jesus.

Apocryphal Gospels are Christian writings which arose primarily in the second century A.D., and which were fanciful, imaginative, and fictitious expansions upon various aspects of Jesus’ life and for ministry. There is a tendency for apocryphal materials to fill in areas which are lacking in the canonical Gospels (such as Jesus’ infancy, boyhood, youth, young manhood, etc.).