Professor Benjamin Mazar, former president of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem and eminent Biblical historian and archaeologist, taught his students how to look at the Biblical text archaeologically, so to speak. Inspired by her grandfather’s methods and insights, Professor Mazar’s granddaughter Eilat Mazar, herself a prominent archaeologist associated with the Hebrew University, thought she could identify the spot on the spur south of the Temple Mount known as ‘Ir David, the City of David, where King David’s palace might be located. In 2005 she began an excavation to test her hypothesis.

Only a dozen years earlier had unequivocal archaeological evidence of King David’s existence been uncovered.a Before that it had been widely claimed that King David was a mythical creature; not even the name David had been found in an ancient archaeological context. Then at Tel Dan, Israeli archaeologist Avraham Biran discovered an inscription created under the auspices of an Aramean king that referred to the “House of David,” a bare century and a half after David’s time.

Perhaps it was time to look for the Israelite king’s palace.

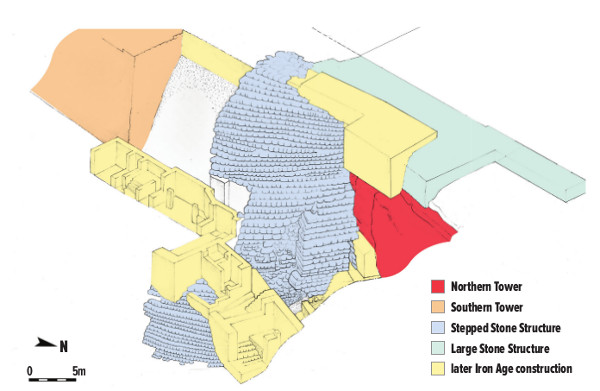

Eilat Mazar has indeed uncovered the remains of a major palatial building. Whether this is King David’s palace has been a hotly contested matter.b With scholarly caution Mazar has dubbed the building the Large Stone Structure (or LSS). She has now published the first volume of her long-awaited excavation report,1 but it does not cover the excavation of the LSS, the candidate for David’s palace. She does tell us, however, that “it seems very likely that the massive structure that we partially unearthed in 2005–2008 … comprises the remains of this [David’s] palace.”

But what is uncontestable is that this is the capital of King David’s kingdom and of the kingdom of Judah in the centuries thereafter. What is perhaps even more important than whether this building is King David’s palace is the picture it gives us of life in the Israelite capital.

In 2007 Mazar’s excavation of the LSS got waylaid, however. The Northern Tower was “in danger of imminent collapse.” This reference to the Northern Tower obviously requires a bit of an explanation—and background.

The City of David is bordered by deep valleys, except on the north, where it is connected to the Temple Mount and the present Old City. On the east, where the LSS would be built, there was a massive gap in the line of the eastern edge of the City of David created by a deep recess where the bedrock turned westward. This created a problem for the ancient LSS architects. The area to the west of this recess had been densely populated for a thousand years. So the ancient builders decided to fill in part of this gap to support their new structure. Thus they created the famous (and long-exposed) Stepped Stone Structure, or SSS, on the eastern side of the City of David. “The Stepped Stone Structure [was] constructed,” Mazar tells us, “to plug the large gap in the natural bedrock and to provide a massive and stable foundation along the steep slope” for the Large Stone Structure.

The Stepped Stone Structure and Large Stone Structure, Mazar explains, “are actually a single, immense complex, most probably built together around 1000 B.C.E.” The SSS served as the foundation for the thick outer wall (labeled W20 in her report) of the LSS. This, Eilat Mazar suggests, is the palace complex built by the Phoenicians [elsewhere Hiram] for King David (2 Samuel 5:11; 1 Chronicles 14:1).

Back to the Stepped Stone Structure: At the southern and northern ends of the SSS are towers. The Southern Tower is by far the larger one. The smaller Northern Tower, however, is what concerns us here. It had been built on earth fills. And it had been undermined by several earlier modern archaeological excavations. In its present condition, Mazar found it to be “in danger of imminent collapse.”

Originally Mazar had no intention of excavating the Northern Tower, but “its steadily deteriorating construction state” led her to conclude that “time was of the essence.” This is what waylaid her from exclusive attention to her excavation of the LSS, the candidate for David’s palace. In 2007 she interrupted her LSS excavation to excavate the Northern Tower of the SSS. Although she undertook this work only because of the deteriorating condition of the tower, the excavation turned out to be enormously productive. And the results of that excavation of the Northern Tower of the SSS provide the major substance of the excavation report reviewed here.

This excavation of the Northern Tower took place in her Area G. By coincidence this was the same area also designated as Area G in the excavations of Yigal Shiloh in the late 1970s and early 1980s. Area G of his excavations became famous when some rock-throwing ultra-Orthodox Jews attempted to stop the excavation based on the unfounded assertion that it had been a cemetery. An Israeli soldier had to police the site in order to allow excavation to continue.

Back to Eilat Mazar’s excavation in Area G. The extraordinary finds from this small excavation are, in an odd way, the result of a terrible illegality and indifference to Jewish history: The Islamic Waqf that controls the Temple Mount decided it wanted to create an additional mosque in the underground hall on the Temple Mount known as Solomon’s Stables. With heavy mechanical equipment and without any archaeological supervision or oversight, the Waqf illegally created a large new stairway down to the area of the new mosque. In the process, they removed hundreds of truckloads of dirt from the Temple Mount that were then dumped into the adjacent Kidron Valley.

There have been 1,263 archaeological excavations in Jerusalem, but not a single one on the Temple Mount. Could anything be retrieved from the mounds of holy dirt (9,000 tons) the Waqf had dumped into the Kidron Valley? To make a long story short, prominent Jerusalem archaeologist Gabriel Barkay and his then-student Zachi Zweig (who has since Hebraicized his last name to Dvira) created what has become a hugely successful project (still far from completion) to wet-sift this dirt. More than 150,000 volunteers have already participated in what has become known as the Temple Mount Sifting Project. The finds have produced objects from as early as 1000 B.C.E. down to the present and include everything from seals, coins and animal bones to mosaic tesserae and arrowheads.

Dry-sifting has long been practiced in archaeological excavations; the excavated dirt is sifted through a sieve to find items that might have been missed during the excavation process. On rare occasions the excavated dirt has been wet-sifted to catch more effectively what might have been missed. The Sifting Project has been so extraordinarily successful,c however, that wet-sifting has become de rigueur at other excavations in Israel, including on Eilat Mazar’s excavation at the base of the Northern Tower. The major part of the excavation report under review here is devoted to the results of her wet-sifting of the excavated dirt from her small excavation at the base of the Northern Tower.

Perhaps the star recovery has been more than a hundred bullae—pieces of hardened clay bearing seal impressions. Typically the lumps of clay were first pressed onto the string that tied up an ancient document; a seal was then pressed onto the soft clay; in this way the seal impression officially identified the sender of the tied document. According to Mazar, the bullae recovered from the Northern Tower excavation originated and fell from the palatial building designated the LSS, which she identifies as David’s palace, although most (but not all) of the bullae come from a few hundred years after David’s reign. The large number of bullae recovered from this small excavation indicate, in Mazar’s words, that “there was a large archive in the palace.” And the administrative activity in this area was intense. The government of Judah was maintained by a sophisticated governmental bureaucracy.

One of the bullae includes a name (ḥym‘ẓ) that appears three times in the Bible (1 Samuel 14:50; 2 Samuel 15:27–36; 1 Kings 4:15), but has never before been found in an archaeological context. The seal impressed in another bulla belonged to a woman. In other respects, the bullae may reflect other aspects of the royal administration at the particular time.

One other aspect of life in the palace may seem trivial: The administrative personnel apparently ate well. Both meat and fish bones were recovered by wet-sifting. The principal bones were of sheep and goats, and a distant third was cattle bones. Very infrequently the scientists from Haifa University who studied the bones found specimens from a camel or a fallow deer. But you guessed it: Of the more than 3,500 animal bones that they identified, not a single one was a pig bone. After all, this was an Israelite city.

The administrative personnel of the palace also appear to have eaten a balanced diet—at least balanced between fish and meat. Many of the more than 3,000 fish bones came from Egyptian fish—some from the Bardawil Lagoon and others from the Nile. The excavation report’s description of gray mullet from the Nile makes my mouth water.

Mazar also uncovered more than a hundred arrowheads and arrowhead fragments, reflecting the ferocity of the Babylonian attack that destroyed Jerusalem and Solomon’s Temple in 586 B.C.E.

This is a very technical excavation report, and few BAR subscribers are likely to read it. Neither will most professional archaeologists. But beneath the technical details is a very human story. Life in the capital of Judah comes alive in a very different way from studying the Bible. Both are valuable, as this book amply illustrates. The volume also exemplifies the intense scientific analysis that is required in a modern archaeological excavation.

MLA Citation

Footnotes

1.

Avraham Biran, “‘David’ Found at Dan,” BAR 20:02.

2.

Avraham Faust, “Did Eilat Mazar Find David’s Palace?” BAR 38:05; Eilat Mazar, “Did I Find King David’s Palace?” BAR 32:01.

3.

Hershel Shanks, “Shifting the Temple Mount Dump: Finds from the First Temple Period to Modern Times,” BAR 31:04.

Endnotes

1.

Eilat Mazar, The Summit of the City of David Excavations 2005–2008, Final Reports, vol. 1 (Jerusalem: Shoham, Academic Research and Publication, 2015).