The Masada Siege—From the Roman Viewpoint

The dramatic archaeological site of Masada, perched on an isolated mesa-top in the Judean desert above the southwest corner of the Dead Sea, is justifiably one of Israel’s premier visitor attractions. The thousands of tourists who come here every year to visit the spectacular ruins of the Herodian fortress-palace exposed by Yigael Yadin’s famous excavation between 1963 and 1965 are treated by their guides to an equally stirring account of the sustained resistance mounted here by a band of determined Jewish fighters against the implacable might of the Roman Empire. Eventually, with their defenses breached and defeat inevitable, the defenders are celebrated for choosing mass suicide over the ignominy of surrender.

This human tragedy derives much of its impact from the austere landscape in which it was enacted, as well as the story of death over dishonor and of resistance to external oppression. This chronicle was ready-made to be harnessed in the fashioning of a suitable ideological narrative in the early days of the new state of Israel.

Although today the tour buses to the Visitors’ Center park under the ramparts of one of the Roman siege camps, and travelers who arrive along the western approach road make their way to the summit along the side of the Roman assault ramp, little direct attention is paid to the extensive archaeological remains of the military campaign that saw the fall of Masada. This article considers the siege not from the heroic viewpoint of the resistance on the mesa-top itself but, instead, from the rather more prosaic perspective of the Romans below.1

The Roman operation against the desert fortress of Masada during the late winter/spring of either 72/73 or 73/74 C.E. represented the final act of the First Jewish Revolt against Rome. This rebellion, which had begun so calamitously for imperial forces with the rout of Syrian governor Cestius Gallus’s army at Beth-Horon in 66 C.E., had proved difficult to contain. Extensive and expensive military campaigns had been necessary to bring the rebels to heel. And the triumph celebrated at Rome in 71 C.E. to commemorate the sack of Jerusalem in the preceding year amounted to a premature declaration of victory. Our main source for the history of the revolt is by a former rebel-commander-turned-quisling, Flavius Josephus. He provides only limited details of the situation in Judea after Jerusalem’s fall, but it is apparent that the Roman authorities were still left with a significant counter-insurgency problem.

The concentration of legions, auxiliaries and client forces that had been necessary to carry out the siege of Jerusalem had been subject to a rapid draw-down after 70 C.E. to the extent that the new governor of the province, Lucilius Bassus, was left with only one legion (and some auxiliary regiments) to deal with the remaining threat.2 “Mop-up” operations in a war that, officially, had already been “won” were scarcely likely to have earned the commander much glory, and the poverty of our literary record probably reflects the prevailing view that Emperor Vespasian’s son, Titus, had already accomplished the hard task of eliminating the enemy’s capital.

Nonetheless Bassus proceeded in a methodical manner to reduce the main hostile concentrations holding out at the fortresses of Herodium (south of Jerusalem) and Machaerus (east of the Dead Sea). Thereafter, he surrounded and wiped out a guerrilla force that had sought refuge in the “Forest of Jardes” (unidentified, but perhaps located in Moabite territory south of Machaerus).

As a result of these actions (concluded in 72 C.E.), the last site to offer continuing Jewish resistance was the isolated fortress of Masada.

Rather than pressing ahead to end matters immediately, Bassus turned to the more urgent task of reorganizing the province in line with the directives he had received from Vespasian, a policy that suggests that the “threat” emanating from Masada was not considered particularly pressing. The defenders of Masada, whom Josephus describes as Sicarii,3 often misleadingly referred to as Zealots, had clearly decided to rely on the strength of their position as their best guarantee against any Roman attack. These Sicarii had seized Masada in the first days of the Jewish Revolt and, although joined by some refugees who had fled after the fall of Jerusalem, their numbers were limited. Josephus claims that there were 967 individuals (both combatants and civilians) still alive within the fortress on the eve of its fall.

Bassus fell ill and died while still in harness. This meant that the reduction of Masada would be left to his successor, Flavius Silva, who was appointed to replace him in 72 C.E. Since the exact date of Silva’s arrival in Judea cannot be determined with certainty, the date of the Roman siege of Masada also remains uncertain. Epigraphic evidence suggests that Silva was still in Italy in the spring of 73, so an operation mounted in late winter/spring 73/74 appears likely. After all, considerable time must have elapsed to allow for the selection of the new governor, for his travel to Judea, and for preparations to be made before he could march against the desert redoubt.4

Regardless of the exact date of the operation, it was clear that Silva would eventually have to tackle this enemy stronghold. To allow the Masada rebels to continue their defiance of Roman imperial might was unthinkable, and the simple expedient of ignoring the defenders until they starved to death risked the prospect of desperate fighters fleeing their bolt-hole and rekindling the rebellion in otherwise pacified territories. No matter the difficulties that a siege might entail, it was essential to bring matters to a decisive conclusion while the enemy (the Jews) remained concentrated in one place.

The Romans were well aware of the extensive arsenal holed up within the fortress, lavishly stocked with both provisions and arms. The capacious cisterns also gave the defenders access to ample water supplies. In these circumstances, a passive siege predicated on the deployment of a relatively small number of troops positioned in blockade camps around the fortress would not have been effective. With the defenders capable of sustaining themselves for an unknowable duration, the Roman besiegers would have required a constant resupply in a hostile environment where foodstuffs and water would have had to be shipped in at great expense. Once the decision had been taken to attack Masada, it was necessary to make a single concerted effort to bring the siege to a close at the earliest possible opportunity.

Silva pressed ahead with the conquest of Masada only after formulating a detailed operational plan. He was not going to risk a hastily improvised assault at the end of attenuated supply lines. Indeed, the Roman governor left little to chance. First and foremost was his decision to concentrate the military resources of the entire province on the task at hand. The main strike force that was deployed was Legio X Fretensis, a veteran formation that had been active in Judea since 67 C.E. onward. The Tenth Legion had participated in repeated siege operations (including Jerusalem and most recently at Machaerus) giving unrivaled experience in the engineering challenges of a siege.

Although the paper strength of the legion may have approximated 5,500 men, it is unlikely that its full complement was deployed at Masada, as some troops must have been held back in supervisory functions elsewhere in the recently pacified province. This would have been particularly true if the operation had taken place in 72/73 rather than 73/74, as there would also have been less time for casualties incurred in earlier actions to have been replenished.

Alongside the citizen soldiers of the legion, Silva would also have made use of auxiliary cohorts drawn from provincial garrisons and may also have had contingents furnished by local client rulers. Although it is impossible to provide an accurate calculation, it is likely that the total manpower deployed in the Masada operation included between 7,000 and 10,000 men. It is also likely that Silva drafted Jewish corvée laborers to act as porters manning his supply lines. Even indirect participants in the operation such as these, however, would have increased the logistical demands on the besieging force, so they would have been kept to a necessary minimum.

Masada is girded by precipitous cliffs and flanked by deeply cut ravines. It had been chosen as one of King Herod’s most spectacular fortress-palaces,5 ostensibly designed to protect the realm against Cleopatra’s overweaning ambitions. Although provided with a simple casemate wall that ringed the summit, bolstered by occasional towers, the real problem for any attacker was overcoming nature itself.

Preparatory to storming the fortress, Silva would have been required to undertake extensive engineering preliminaries (1) to prevent the escape of any defenders and (2) to enable his troops to mount an attack against the enemy wall.

Modern scholars can be thankful that the isolation of the site and the aridity of the environment allow an unrivaled opportunity to examine the material remains of Silva’s siege operation and to correlate the surviving archaeological record with Josephus’s narrative. Indeed, Masada gives us our most complete surviving siege system of the ancient world.

The investigation of the Roman field works at Masada has been on a much more limited scale than the extensive excavations conducted on the mesa-top itself. In the early 1960s, Shmaria Gutman investigated (and reconstructed) Camp A in the Roman siege system while Yadin conducted test-pitting in Camp F. In 1995 Benny Arubas, Gideon Foerster, Haim Goldfus and Jodi Magness undertook the first modern examination of some of the other Roman structures. Apart from Magness’s pottery report, however, the results of these excavations have yet to be published.6 Therefore our understanding of the Roman siege works at Masada must be derived from combining the account in Josephus with a field inspection of its surviving component elements.

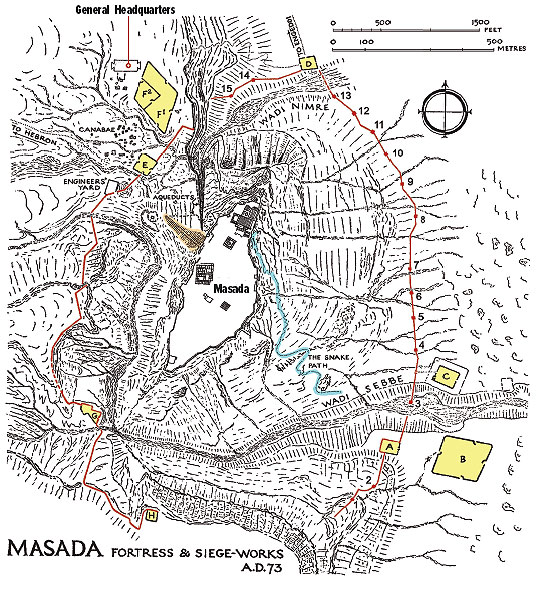

Josephus informs us that Silva’s first operational order after deploying his men in various garrison posts around Masada was to ensure the hermetic sealing of the fortress: Silva “threw up a wall all around the fortress to make it difficult for any of the besieged to escape, and posted sentinels to guard it.”7 This circumvallation wall, much of which still survives, extends for more than 2.5 miles and circles the entire site.

This was a standard operating technique of the Roman army and had been deployed elsewhere during the Jewish Revolt, most notably at Jerusalem, Machaerus and Yotapata. At Masada it comprises a wall of rough stone blocks that retain a rubble core. It still stands up to seven courses high in places. It is more than 5 feet wide and probably had an original height of about 10 feet. Quite remarkably, Silva extended it across very difficult terrain, even in sectors where an escape attempt would have been next to impossible. The only gap in the wall lies along the plateau to the south where a sheer cliff plunges down to the wadi making any artificial barrier redundant.

The relentless pursuit of a monolithic building scheme even at the expense of strict military necessity suggests that the Romans were consciously adopting a form of psychological warfare by ramming home to the rebels the message that they were now completely isolated without any hope of relief or escape. This message might also have served as a salutary reminder to any client forces present of the implacable determination of the Roman state to pursue rebels to the very ends of the world and to inflict due retribution for their defiance.

Along the eastern and northern stretches of the circumvallation wall, the besiegers added a series of 15 turrets on which could be mounted light catapults. Ten of these turrets are positioned along the circumvallation wall where it runs beside the relatively flat plain at the base of Masada’s eastern cliff. This is the side on which the Snake Path descends from the summit; these turrets would have provided fire support in the event of a rebel attempt at a sortie. The remaining turrets seem to have been positioned to provide flanking fire in the event of any attempt to break out along the stream-beds of either the Wadi Nimre or Wadi Sebbe.

Eight camps (designated A though H) to house the besieging force are distributed around Masada. The largest of these, Camps B and F, include nearly 5 acres each. Presumably these two camps served as the bases for the soldiers of the Tenth Legion, with each camp exerting command and control functions over the eastern and western sectors of the circumvallation wall.8 Camp B would have been best suited to act as the main depot for the entire system (where supplies transported along the Dead Sea could have been stored), while Camp F would have acted as Silva’s operational headquarters from which the assault preparations would have been directed.

The 1995 excavations at Camp F recovered a few examples of high-quality pottery and glass largely concentrated in one area, suggesting that Silva’s personal quarters were located here.

The discrete patterning of the scatter of stones within the walls of the camp allows us to roughly reconstruct the camp’s internal buildings. Given the temporary nature of the operation and the local scarcity of timber, these Roman buildings would have consisted of tent units raised on top of dwarf stone walls designed to increase internal headroom and to improve the circulation of air. Most of these structures represent the tent lines of the troops themselves. Some other “buildings” have also been identified, for example, a probable hospital in Camp B.

Apart from the main legionary bases (Camps B and F), the six other camps in the system (roughly an acre in size) would likely have served as garrison points for auxiliary units manning the circumvallation wall. Five of these camps butted up directly against the circumvallation wall, while Camp C, likely the base for a cavalry unit tasked with patrolling the most vulnerable sector, was recessed immediately behind the encircling circumvallation wall. It seems that each of these smaller camps was also designed to perform various specialist functions. Camp E, for example, is located behind the Roman assault ramp; it had two gateways through its front defenses, presumably to allow for the rapid reinforcement of those working on the ramp in the event of any serious hostile sortie. Camp H, isolated on the scarp edge above the Wadi Sebbe, was primarily designed as an observation post enjoying sweeping oversight across the Masada mesa-top. The irregular “key-hole” configuration of Camp G suggests that the Romans may have extended this particular base while the siege was in progress, perhaps because its original design did not allow for adequate supervision of the streambed of the Nahal Masada.

One other enclosure attached to the back of the circumvallation wall, located west of the assault ramp, is usually referred to as “the Engineering Yard.” It is a leveled platform where traces of metal working activities have been detected by Ian Richmond in the early 1960s.9 It is likely the place where the ironclad Roman siege tower was put together. Josephus claims this siege tower was nearly 100 feet high. This engine, presumably transported to the site in prefabricated segments, would have required a secure site for its assembly, and it would have made sense to select a place only a short distance from the point at which it would eventually be deployed. Perhaps appropriately (if archaeologically unfortunate) the National Park Authority has chosen to locate its modern works and storage depot at exactly this site, so there is little chance of recovering any further details of this Roman establishment.

Various other structures, mostly one-to-three-roomed tent units, can be found scattered along the hillside in the vicinity of Camps E and F. These are probably canabae, civilian settlements supporting the military. The Masada canabae have been variously interpreted as the premises of camp followers engaged in providing services for the Roman siege force or, perhaps more likely, as the accommodations for the Jewish corvée. Although most of these appear to be very simple structures, some units enjoy a more complex plan, including hallways and dining areas, suggesting that they may represent the communal mess facilities for these draftees. The relatively flimsy nature of most of these remains and their exposure to run-off as well as their proximity to the modern son-et-lumière complex make it urgent that some of the more vulnerable examples of these canabae be investigated archaeologically before further evidence is lost.

The careful disposition of these camps and ancillary structures evidences the methodical and deliberate nature of Silva’s campaign to suppress the rebels on Masada. However necessary these measures may have been for isolating the defenders and for making the besiegers’ task more feasible, the construction of the circumvallation and its related works were mere preliminaries to the direct approaches that would be necessary if Masada itself was to be secured. For that a siege ramp was needed.

The most striking surviving image of the Roman siege works at Masada is the great assault ramp (or agger) that Silva’s men threw up against its western slopes. This was the only flank on which it might have been constructed, not least because it is the location of a natural spur (called the Leuke, or “white promontory,” by Josephus10) that abuts the isolated mountain. The underlying geology certainly exaggerates the seeming Roman construction of the ramp; the artificial deposition of material consists only of about 90 feet above bedrock; in short, much of the ramp consists of bedrock.a The manipulation of the environment that it entails nevertheless reminds us of the Roman determination to expunge the last vestiges of the Jewish rebellion.

The ramp is almost 750 feet long and about 650 feet wide at its base, narrowing as it climbs to about 150 feet at the top, which is about 240 feet above its base.11 Oddly enough, this is still 42 feet short of the Masada summit.

Josephus notes that the ramp was once crowned by a stone platform. This stone cap or platform would have served as a reinforced base for the siege tower that housed the Romans’ battering ram and would have raised this engine to within striking range of the defenders’ casemate wall. Although no trace of this platform remains in situ today, the extensive talus (the stone field) on both sides of the ramp may represent the debris that in time toppled from this structure. Early visitors to the site remarked on this feature of the ramp.

The main body of the ramp is composed of stone and earth reinforced by timber bracing that still projects in places above the surface. These timbers of tamarisk and other arid-environment tree species seem to have formed a box-revetment filled with compacted earth and small stones. Presumably this revetment would have been situated on a series of ascending parallel steps that the Roman engineers would have hacked out of the bedrock as they proceeded to “bench” each side of the spur, much as modern engineers sometimes scarp the sides of highway cuttings today. The resulting double flight of steps ascending the slope would then have accommodated the box-revetment. With the flanks of the spur now stabilized, the intervening space between the timber revetments would be filled with dumped material that was then consolidated by ramming.

The entire point of this ramp was to serve as an approach path for the siege equipment to be deployed directly against the defenders’ casemate wall. The angle of the ramp had to be carefully calculated to ensure that the siege tower could be raised into position. The siege tower was an ironclad structure nearly a hundred feet tall, according to Josephus. It was designed to resist incendiary attack by the rebels. The siege tower contained the ram housing, artillery for clearing the defenders from their parapets and extensible gangways to allow the storming party access to the enemy defenses. Once the ramp had been completed and a timber track laid on its surface, the siege tower would have been elevated with a winch in short incremental steps. If the defenders made no serious attempt at a disruptive sortie (and Josephus does not mention any), the tower’s elevation from the base of the ramp to its summit may have taken only a few hours.

Although recent accounts have been published suggesting that the assault ramp had not been completed by the time that Masada fell to Silva,12 this hypothesis seems very unlikely. To begin with, if the ramp was incomplete, it is not clear how the Romans would have succeeded in breaching the enemy defenses which they clearly did. Secondly, it is surely not coincidental that the location of the breach in the defenders’ casemate wall lies immediately above the modern summit of the ramp. Thirdly, the distribution of stone ballista projectiles recovered from an arc of loci within the fortress suggests the field of fire that would have come from catapults mounted on a siege tower; the siege tower would not have been raised into position had the ramp not been completed.

Despite the impressive scale of these Roman works at Masada, there is little reason to suppose that the siege would have taken much more than three months to bring to a conclusion.

Josephus states how Masada’s primary defenses were first overthrown by ram-strikes. Then the rebels’ hastily extemporized secondary defenses were consumed in an incendiary attack. That night, with further resistance now impossible, Josephus relates how the defenders, encouraged by their leader Eleazar Ben-Yair, entered into a suicide pact rather than face the inevitability of retribution when Roman forces entered the fortress at dawn. When the Roman troops entered, they met only silence.

MLA Citation

Footnotes

See Dan Gill, “It’s a Natural—Masada Ramp Was Not an Engineering Miracle,” BAR 27:05.

Endnotes

For a more detailed account of the Roman siege system employed at Masada, see Gwyn Davies, “Under Siege: The Roman Field Works at Masada,” Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research 362 (2011), pp. 65–83.

It seems that after the fall of Jerusalem, Judea was organized in an unusual way so that the provincial governor was also, simultaneously, the commander (or “legate”) of its one legion garrison.

A violent sect who engaged in the assassination of their many political enemies in the pursuit of their messianic goals.

The alternate view of 72/73 is largely based on the discovery of a fragmentary papyrus from the Masada summit (presumably attributable to the Roman garrison left in place after the fall of the fortress) addressed to one Julius Lupus, possibly the same individual appointed as Prefect of Egypt in February 73, implying that the fortress must already have fallen to the Romans by that date. However, it is equally possible that this was a copy of a letter (or even an original that was never sent) written by an author who belonged to the post-conquest Masada garrison. For more details see Hannah M. Cotton and Joseph Geiger, Masada II: The Yigael Yadin Excavations 1963–1965, Final Reports: The Latin and Greek Documents (Jerusalem: Israel Exploration Society, 1989), pp. 21–23.

See Amnon Ben-Tor, Back to Masada (Jerusalem: Israel Exploration Society, 2009) for a lively summary of the eight volumes of reports that have so far been published from Yadin’s excavations.

Jodi Magness, “The Pottery from the 1995 Excavations in Camp F at Masada,” Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research 353 (2009), pp. 75–107.

Josephus, The Jewish War, VII.276, H. St. John Thackeray, ed. and trans., Loeb Classical Library (Cambridge, MA: Harvard Univ. Press, 1927).

The steep escarpment edge of the rift valley would have provided a natural delimitation between the two operational sectors, although a carefully engineered zigzag track exiting from Camp D served as a link between the two zones.

Ian A. Richmond, “The Roman Siege-Works of Masada, Israel,” Journal of Roman Studies 52 (1962), p. 154.

Josephus seriously overstates the dimensions of Silva’s agger. See Josephus, Jewish War VII.307.