The Monastery of the Cross: Where Heaven and Earth Meet

032

Many years ago, before I had married and gone to work as an archaeologist at the Israel Antiquities Authority, I lived for five years in the Monastery of the Cross as a Greek Orthodox monk. So I know the complex well.

According to legend, the tree that furnished the wood for the cross of Jesus once grew on the very spot where the Jerusalem monastery now stands. Until the 15th century, pilgrims attested that they could look behind the altar of the monastery’s church to see what remained of the trunk, still in the ground. Today the site is enclosed within the crypt chapel to the left of the church.

According to one tradition, the place where the tree had grown was identified in the fourth century by Queen Helena, mother of Constantine the Great, the first Christian emperor, after she had discovered the “true” cross on Golgotha. The tradition claims that it was she who founded the monastery church, but this tradition, which can be traced back only to the 18th century, is probably not authentic. True, the church is dedicated to St. Helena, her son Constantine and the Exaltation of the Cross, but an association with the pious St. Helena has long enhanced the prestige of any shrine. Thus many churches and monasteries trace their origin to her.

A 16th-century legend holds that Constantine gave the site to a Georgian prince from the Caucasus named Myrian (265–342 A.D.) upon his visit to the Holy 034Land and that, a century later, another Georgian prince, Tatian, erected the monastery there. But it has never been historically verified that Myrian ever visited the Holy Land, and it is doubtful that a ruler named Tatian even existed in Georgia.

There may be more truth to another tradition, which suggests that the emperor Justinian founded the monastery in the sixth century at the request of a Georgian prince named Myrvan, who did indeed visit the Holy Land as a pilgrim in the fifth century. During his stay in Jerusalem Myrvan decided to become a monk and founded a monastery near the present David’s Tower. At the beginning of the sixth century he was ordained a bishop and, under the Christian name Petros (Peter), served in the episcopate of Gaza-Maioumas.

According to still another tradition, the monastery was founded by the Roman emperor Heraclius at the beginning of the seventh century. In 614, the Persians captured Jerusalem from the Byzantine Christians, but in 630 Jerusalem was re-taken by Christian troops led by Heraclius. Before they entered the Holy City, Heraclius and his army had camped in what is now the Valley of the Cross. During his campaign, Heraclius also recaptured from the Persians the relics of the cross (pieces of wood believed to be fragments of the real cross of Jesus), which he returned to Golgatha for public veneration. Several years later he founded the church and monastery in the Valley of the Cross, where his victorious troops had camped.

The founding traditions involving Justinian and Heraclius probably are more authentic than the others; Both Justinian and Heraclius are closely associated with the construction and renovation of a large number of churches and monasteries in the Holy Land. It is plausible that the Monastery of the Cross was founded by Justinian in the middle of the sixth century. The Persians then destroyed it in 614 (along with many other churches and monasteries) when they captured Jerusalem, and Heraclius restored it after his victory over the 035Persians in 630. In any case, we do have evidence of the monastery’s existence in the sixth or seventh century. A manuscript in the Library of the Greek Orthodox Patriarchate of Jerusalem describes the condition of the Church of Jerusalem in that period and lists the monasteries then extant in the environs of the Holy City. Among them is the Monastery of the Cross.

The decisive confirmation of the monastery’s Byzantine origin, however, comes from archaeology. From 1969 to 1973, the Greek Orthodox Patriarchate of Jerusalem performed large-scale conservation work in the monastery, during which the entire mosaic pavement of the monastery’s church (which dates to the 11th century) was removed, re-set on a new solid base and then returned to its original position. While the mosaic was gone, the head archaeologist/architect, Athanasios Oikonomopoulos, conducting a somewhat improvised archaeological examination, found another mosaic pavement beneath. Based on stylistic evidence and pottery finds, the floor can without doubt be dated to the sixth century.

Christian tradition links the site to the Biblical patriarch Abraham and his nephew Lot. The Bible says that when the three angels who visited Abraham departed, they proceeded to Sodom (Genesis 18:16), presumably to see Lot. Before departing, according to this tradition, the angels left their three staffs with the Patriarch. Abraham then argued with God to save Sodom and 037Gomorrah from destruction (Genesis 18:32), but Sodom and Gomorrah were soon destroyed. For Abraham’s sake, however, Lot and his two daughters were saved; Lot’s wife looked back at the destruction and became a pillar of salt (Genesis 19:26–30). According to the Bible, Lot’s daughters each seduced him after plying him with strong drink on successive nights; they later gave birth to the ancestors of the Moabites and the Ammonites (Genesis 19:31–38).

Although the Bible says that Lot was not cognizant at the time of his incestuous sin, Christian tradition does not hold him blameless. When he later met Abraham, he asked him what he must do to atone. According to the legend, Abraham gave Lot the three staffs of the visiting angels and told him to plant them near Jerusalem and to water them with water from the Jordan River. If the staffs were to blossom, it would be a sign that God had forgiven Lot’s transgression. Lot did as Abraham instructed. He planted the staffs outside the walled city in the valley where the monastery now stands, and managed to carry water there from the Jordan River despite Satan’s attempt to divert him. As soon as he watered the staffs, they blossomed and grew into a triple-branched tree. One branch was pine, another cedar and the third cypress.

In the 16th or 17th century, the story was again embellished: During King Solomon’s reign, the tree was used to supply timber for the Temple. The timbers would fit nowhere, however. They were discarded as useless and accursed. These accursed beams were then used in Jesus’ time to make the cross for his crucifixion. And the monastery was erected on the spot where Lot had planted the staffs of the angels.

Another legend connects the monastery to the treasures of the second Temple, which the Romans had stolen in 70 A.D. when they captured Jerusalem and destroyed the Temple. Some of these treasures are shown on the Arch of Titus in Rome. Justinian’s general, Belisarius, is said to have recovered the Temple treasures when he recaptured Rome in 536 from the Vandals and other barbarians (who had conquered Rome in 410). Belisarius later placed the treasures in the magnificent Nea Church, which Justinian had built in Jerusalem and dedicated to the Virgin Mary. (Not long ago, archaeologists excavating near the Dung Gate discovered remnants of Jerusalem’s Nea, or New, Church, also known as the Theotokos—mother of God.a) When the Persians attacked Jerusalem in 614, Christians hid the vessels outside the city, in the Monastery of the Cross. In 796 Arab Muslims raided the monastery and killed all the monks. As a result, the hiding place of the Temple vessels remains unknown to this day. Even now, some, including scholars, believe that the treasures are still hidden somewhere in the huge monastery.

Indeed, the monastery would have been a good place to hide the Temple treasures in 614. The compound lies in a fertile valley west of the Old City, now in the heart of the modern city. It has been destroyed, damaged, restored, repaired and expanded many times over the centuries. In 1009 the Fatimid caliph, Hakem, destroyed the Church of the Holy Sepulchre along with many other churches and monasteries, among them doubtless the Monastery of the Cross. We know it was restored beginning in 1017 by one Prochorus, a Greek monk from Mt. Athos in Athens. He was apparently the first to decorate the walls of the church with pictures of the saints and episodes from the Bible. Prochorus received financial help not only from the Greek Patriarchate of Jerusalem, but also from the king of Georgia. Until this time the monastery had housed both Greek and Georgian orthodox monks, but after Prochorus’s restoration, the monks were predominately from Georgia. Only a few monks were brought by Prochorus from the Mt. Athos monasteries in Greece. From the 11th to the 17th century the monastery continued as the center of Georgian monasticism in the Holy Land.

Then along came the Crusaders, who occupied Jerusalem in 1099. The fervently Roman Catholic army, suspicious of Eastern Orthodox Christianity, seized all of the monastery’s vineyards, from which the monks gained their sustenance. Not until after the Muslims expelled the Crusaders in 1187 were hundreds of acres of cultivated land restored to the monastery.

A new period of prosperity ensued. The number of Georgian monks substantially increased. Gifts from Georgia, an ascendent power in the Black Sea region at the time, made the Monastery of the Cross one of the richest in the Holy Land. Queen Tamar of Georgia 040(1184–1213) sent the national poet of Georgia, Shota Rustaveli, to Jerusalem to reorganize the Georgian monastic movement there and to repair the damage inflicted on the Monastery of the Cross during Crusader rule.

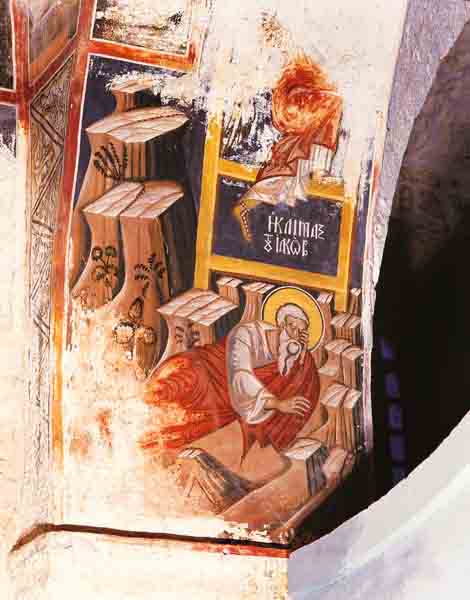

It may seem strange to send a poet for this purpose. One story has it that he was in fact Queen Tamar’s lover and was sent to Jerusalem to get him out of the palace and to deflect the malicious gossip about their affair. In any event, he, like Prochorus, commissioned artists to create beautiful works for the walls of the church. His design included not only saints and Bible figures, but pre-Christian Greek intellectuals, such as Plato, Socrates, Aristotle, Solon, Thucydides and Plutarch. Up to the 14th century visitors attested to seeing these paintings, but unfortunately, hardly a trace of them survives today.

In 1960, about 760 years after Shota Rustaveli had completed his restoration, three Georgian academics knocked on the door of the monastery. I was then a deacon of the Greek Orthodox Patriarchate of Jerusalem and was living in the monastery. Thus, I was the first to give them a glad hand and the traditional Greek coffee. They later obtained permission from the Greek Patriarchate to search for a portrait of Shota Rustaveli. Following descriptions of earlier visitors, they began to remove the paint from a darkened part of a wall painting on the second right pier of the church. After several days of careful work with chemical solvents, the delegation removed the dark paint that covered the middle part of the pier. And what a surprise! There, between the standing figures of Saint Maximus and Saint John of Damascus, appeared in vivid and glowing colors the portrait of a kneeling Georgian figure dressed in a long mantle and round cap. Above the portrait was a four-line inscription in white written in an ancient Georgian script: “Lord, remember your servant Shota, who did all this. Amen.”

In the 13th century, Arab raiders drove out the Georgian monks and converted the church into a mosque and the monastery into a theological school for dervishes (members of Muslim ascetic orders). By the first decade of the 14th century, however, the monastery was back in Christian hands, restored to its position as the center of Georgian monasticism in the Holy Land. The monastery prospered until the Ottoman Turks took control of Palestine in the 16th century. The fortunes of the monastery declined, as much from internal dissension as from Turkish rule. At one point creditors even threatened to seize the monastery. Money sent from Georgia to settle the debts was lost on the way. The monastery was saved only at the last moment when the Greek Patriarchate of Jerusalem raised funds in Orthodox countries (including Georgia) to pay the creditors. As a result, the Monastery of the Cross came under the administration of the Greek Orthodox Patriarchate of Jerusalem in the 17th century and since then has been an integral part of its spiritual and landed property. The Greek Brotherhood of the Holy Sepulchre absorbed the few Georgian monks remaining in Jerusalem. And so, after a splendid 600-year history in Jerusalem, the Georgian monastic community had all but disappeared.

In 1855 a theological school was established, inaugurating a splendid new period in the monastery. Monk’s cells (there had been as many as 300 of them) were transformed into lecture rooms. Thousands of books were added to the monastery’s library. New chapels were added for daily prayers; at one time there were seven chapels in addition to the central church (today only two are left). Three floors were added to the main building, making it a five-story structure, and the belfry tower was built. The largest hall of the compound was turned into the first museum in Jerusalem, which included archaeological finds and other objects from Palestine.

041

With few interruptions, the theological school remained open until 1908, when it was closed because of financial difficulties. Another period of decline set in. For decades the only person living in the monastery was the abbot. That remains the case today. The abbot’s mother is now the caretaker. After several years of renovation and conservation (from 1969 to 1973), the late Patriarch of Jerusalem, Diodorus 1, opened the monastery to the public, hoping to restore the monastery to its preeminent position.

The monastery is well worth a visit: the high ancient walls, off-white with age; the imposing dome of the church; the roofs of different heights of various domestic and ecclesiastical structures, some covered with reddish ceramic tiles and others with stone slabs; the elaborate bell tower—all give the compound the feel of an impregnable medieval castle.

Inside, the two old cypress trees that pilgrims have described since the 16th century still grow in the courtyard. The entire complex is a testament to a 1,400-year history of glory and suffering. The early fragments of mosaic pavement take us back to Byzantine times. The Georgian inscriptions written on the walls and under the painted icons remind us of the Georgian monastic presence. The Greek inscriptions refer us to the history of the last 400 years. The bell tower and huge halls in the upper two floors tell the story of the theological seminary. In the library of the seminary, alas now closed on the third floor, hundreds of volumes are carefully arranged on the shelves just as they were left in 1908 when the theological school closed.

The church is undoubtedly the most striking part of the complex. It is the oldest completely preserved Christian church in Jerusalem. The mosaic floor from the 11th century, with its intricate geometric designs and colorful birds and animals, has survived intact. The medieval wall paintings of scenes from the Old Testament and the life of Jesus, as well as portraits of saints—now fragmentary, pale and smoky—still have the power to move. A high dome at the center of the church shows the Holy Trinity surrounded by angels and other celestial beings.

Visitors should recognize, however, the overall theological scheme presented by the art in the church. The pavement represents the earth, the habitation of all humans, animals and plants. The walls and pillars are the intermediary between heaven and earth. Scenes from the Old and New Testaments—Daniel in the Lion’s den, Elijah ascending to heaven, events from the earthly life of Christ (the Annunciation, the Crucifixion, the Resurrection and many more)—unite heaven and earth. The icons of saints plead for humanity with God, the Father who sits at the center of the dome with Jesus at his right hand.

Many years ago, before I had married and gone to work as an archaeologist at the Israel Antiquities Authority, I lived for five years in the Monastery of the Cross as a Greek Orthodox monk. So I know the complex well. According to legend, the tree that furnished the wood for the cross of Jesus once grew on the very spot where the Jerusalem monastery now stands. Until the 15th century, pilgrims attested that they could look behind the altar of the monastery’s church to see what remained of the trunk, still in the ground. Today the site is […]

You have already read your free article for this month. Please join the BAS Library or become an All Access member of BAS to gain full access to this article and so much more.

Already a library member? Log in here.

Institution user? Log in with your IP address or Username

Footnotes

See Meir Ben-Dov, “After 1,400 Years—The Magnificent Nea,” BAR 03:04.