The Nash Papyrus—Preview of Coming Attractions

043

On Wednesday, February 18, 1948, John Trever, a fellow at the American School of Oriental Research in Jerusalem, answered a telephone call asking if the caller could bring by some ancient Hebrew manuscripts for him to look at. It was the last days of the British Mandate over Palestine, the Old City was ringed in barbed wire entanglements, and violence was rife. Trever was more concerned with the safety of the school and the people there than for old manuscripts. But, his curiosity piqued, he invited the caller, a Syrian Orthodox monk he knew named Butros Sowmy, to come by the next afternoon.

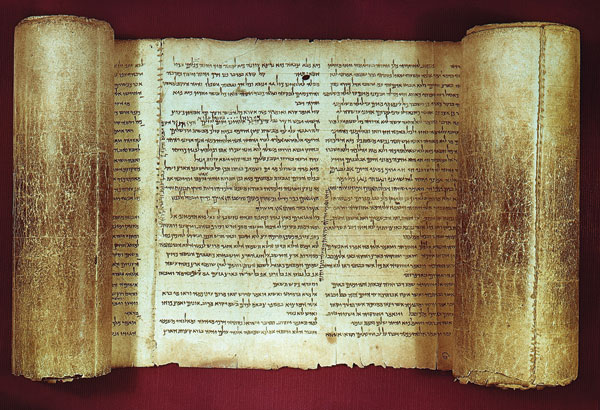

Among the manuscripts Sowmy brought with him was a virtually complete copy of the Book of Isaiah (so-called Isaiaha), one of the original seven Dead Sea Scrolls discovered by Bedouin in a cave near Qumran in the Judean Desert.

Sowmy left the manuscripts to be photographed (Trever was a near-professional photographer)—and studied. Were they really ancient? As Trever examined the letters of the Isaiah Scroll under a magnifying glass, trying to date the writing, he recalled an article by the doyen of Biblical and archaeological 044scholars, William Foxwell Albright of The Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore, about a Biblical fragment known as the Nash Papyrus. Albright had dated the Nash Papyrus to the first or second century B.C.E. The letters in the Isaiah Scroll paleographically resembled the letters of the Nash Papyrus, which was then the oldest known Hebrew manuscript containing a Biblical text!

“My heart began to pound,” Trever writes in his memoir from which this account is taken.1 “Could this manuscript, so beautifully preserved, be as old as the Nash Papyrus? Such a thought appeared too incredible, but similarity to the Nash Papyrus was strong evidence leading in that direction.”

Further study seemed to confirm Trever’s initial impression. On February 26, Trever sent a letter to Albright together with some photographs of the scroll:

if you are right about your dating of the Nash Papyrus, then I believe that this is the oldest Bible document yet discovered! … I know you will understand my concern about the safety of the MSS, so you will keep this absolutely confidential. Should there be an announcement, there is great danger that they might be destroyed.

Albright replied almost immediately after receiving Trever’s letter and photographs:

My heartiest congratulations on the greatest MS discovery of modern times! There is no doubt whatever in my mind that the script is more archaic than that of the Nash Papyrus … I should prefer a date around 100 B.C.

Albright also compared the orthography (spelling) of the scroll to the Nash Papyrus:

I repeat that in my opinion you have made the greatest MS discovery of modern times—certainly the greatest biblical MS find. The spelling is most interesting, resembling that of the Nash Papyrus very closely … The new material will revolutionize our conception of the development of Hebrew orthography …

You can imagine how my eyes bulged, when I saw the script through my magnifying glass! 045What an absolutely incredible find! And there can happily not be the slightest doubt in the world about the genuineness of the MS.

All this based on the Nash Papyrus. So what is this Nash Papyrus on which the Dead Sea Scrolls were first dated and authenticated?

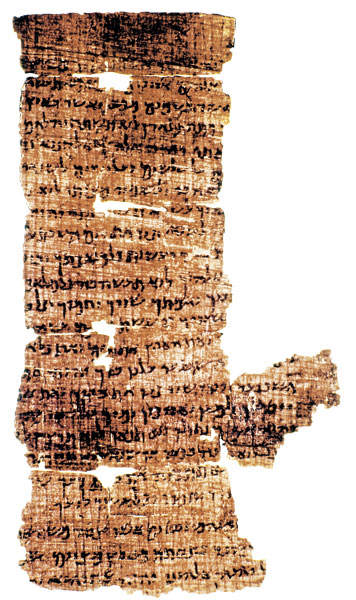

The papyrus was purchased from an Egyptian antiquities dealer in 1902 by W.L. Nash, F.S.A. (Fellow of the Society of Antiquaries), the secretary of the now-defunct Society of Biblical Archaeology in England (no relation to the Biblical Archaeology Society, publisher of BAR). According to the unreliable report of the dealer, the papyrus came from Fayuum, a city about 80 miles southwest of Cairo; and, if not from Fayuum, from somewhere else in Egypt. It is now part of the Cambridge University Library Oriental collection (Ms. Or. 233).

By the time Nash acquired it, the papyrus was in four adjoining pieces. The largest piece is just under 2 by 4 inches. With the pieces together, it is 3 by 5 inches. The 25 lines of square Hebrew text consist primarily of the Ten Commandments and the Shema‘ (Deuteronomy 6:4: “Hear O Israel, the Lord our God, the Lord is One”).

The Nash Papyrus was published in 1903 by S.A. Cooke,2 who dated it paleographically (on the basis of the shape and form of the letters) to the second century C.E. More than three decades later, however, the available comparative texts (from nonbiblical inscriptions) for dating the Nash Papyrus had increased enormously. When Albright took a new look at the Nash Papyrus, he redated it more than 200 years earlier than Cooke, to the second or first century B.C.E.3 That date has been widely accepted and has now been confirmed by texts that have become available since Albright’s 1937 study. This made the Nash Papyrus the oldest Biblical manuscript prior to the discovery of the Dead Sea Scrolls.

Although the Nash Papyrus may have been the oldest Biblical manuscript, it is not a Bible manuscript. That is, it is not from a copy of the Bible, as is clear from the fact that it is on a single sheet of papyrus and contains texts from different parts of the Bible.

Hence, it was not part of a Torah scroll, but most probably an early liturgical text used in a prayer service by a Jewish community somewhere in ancient Egypt. The Mishnah (Tamid 5:1), the earliest known document of Rabbinic Judaism, written around 200 C.E., indicates that the Ten Commandments were read immediately prior to the Shema‘ in the Jewish prayer service during the Greco-Roman period. The Babylonian Talmud (Berakot 12a), compiled in about 600 C.E., indicates that the practice of reading the Ten Commandments as part of the Jewish worship service was discontinued due to claims made by early Christians that such practice demonstrated that the Ten Commandments were the only valid portion of the Torah. Although the Ten Commandments are no longer read as part of the service in the synagogue, the Shema‘ is frequently invoked. The Shema‘ is also cited by Jesus 047as the first Great Commandment in Mark 12:29.

The Bible actually contains two versions of the Ten Commandments: one in Exodus (20:1–17) and the other in Deuteronomy (5:6–21). And they are not identical. In Exodus they are the words God speaks to Israel at Mt. Sinai. In Deuteronomy Moses recounts God’s words.

The Ten Commandments in the Nash Papyrus is actually a third version. Both Bible versions begin: “I am the Lord your God who brought you out of the land of Egypt, out of the house of bondage.” The Nash Papyrus omits the last phrase (“out of the house of bondage”). No doubt this phrase was omitted due to the sensitivity of the Egyptian Jewish community: Egypt was no longer a house of bondage. Jews were generally granted relatively high status in Egypt during the Hellenistic period, although restrictions were later imposed during the Roman period.

The two versions of the Ten Commandments in the Bible differ, especially in the Sabbath commandment. In Exodus the Israelites are commanded to “Remember the Sabbath day and keep it holy,” while in Deuteronomy they are commanded to “Observe the Sabbath day and keep it holy.” On this one, the Nash Papyrus agrees with Exodus.

In other instances the Nash Papyrus agrees with Deuteronomy. Further in the text of the Sabbath commandment, the Exodus version recites that even your “cattle” should have a day of rest. Deuteronomy, too, includes your “cattle,” but “your ox” and “your ass” are inserted before the cattle. In this instance the Nash Papyrus agrees with Deuteronomy and specifically includes a rest for the oxen and asses.

There is also reason to believe that the Nash text of the Ten Commandments was influenced by the Septuagint. The Septuagint (often abbreviated LXX, the Roman numerals for 70) is a Greek translation of the Hebrew Bible prepared beginning in the third century B.C.E. for Jews in Alexandria who did not read Hebrew. According to legend, 72 scholars were isolated individually to come up with a Greek translation, and each came up with exactly the same translation!

One small indication of the Septuagint’s influence on the Nash text is in Line 10, part of the Sabbath commandment. The Nash Papyrus has “but on the seventh day …” like the Septuagint. The Hebrew of the Masoretic text (or MT), which preserves the standard Jewish text, has “and the seventh day …” in both Exodus and Deuteronomy. On this occasion, the Nash Papyrus agrees with the Septuagint. What we don’t know, however, is whether the Septuagint translator mistranslated the word or whether he was working from a different Hebrew text.

048

Another trace of the Septuagint appears in the next line, Line 11. The Masoretic text says, “You shall not do any work.” The Nash text, like the Septuagint, says, “You shall not do any work on it.” These differences may seem trivial, but they are telling.

The Sabbath commandment is especially different in Exodus and in Deuteronomy regarding the reason for it. According to Exodus, the Israelites are to remember the Sabbath day in relation to God’s creation of the world and his rest on the seventh day. In Deuteronomy the Sabbath is to be observed to commemorate God’s redemption of the Israelite slaves from Egypt. Here the Nash text follows the Exodus version.

Obversely, in the command to honor one’s parents, the Nash Papyrus follows Deuteronomy. Like the version in Deuteronomy, the Nash text adds the phrase “in order that it will go well with you” to justify the command to honor one’s parents. This phrase does not appear in the Exodus version.

The Nash text also presents a different order of the succinct prohibitions against murder, adultery, theft and bearing false witness. The Nash text reverses the order of the first two, placing adultery ahead of murder. In this, Nash follows the Exodus account in the Septuagint.

At the end of the Ten Commandments, the Nash text adds a little summation (here partially reconstructed): “And these are the statutes and commandments that Moses commanded the sons of Israel in the wilderness when they went out from the land of Egypt.”

This does not appear after the Ten Commandments in either Exodus or Deuteronomy, although this addition may be derived from elsewhere in Deuteronomy (Deuteronomy 4:45).

There are a number of other small variations in the Nash text as compared to the Hebrew Masoretic text in Exodus and Deuteronomy (and to the Septuagint), but this is enough to indicate their flavor.

After this in the Nash text is the Shema‘: “Hear, O Israel, the Lord (YHWHa), our God, the Lord (YHWH), He is one.” This follows Deuteronomy 6:4–5 with, however, the addition of the word “he,” which I have italicized. This is a much clearer reading.

The Nash Papyrus is clearly an eclectic text that combines readings known from several versions of the Ten Commandments, including the traditional Hebrew texts of Exodus 20 and Deuteronomy 5, as well as the Hebrew text that presumably stands behind the Greek Septuagint. On the other hand, it also maintains its independence as shown by the excision of the phrase “out of the house of bondage,” no doubt in deference to the sensitivities of a community of Jews in Egypt in the years when the Temple still stood in Jerusalem.

Although some might have been tempted to rewrite the versions of the Ten Commandments in their Bible following the discovery of the Nash Papyrus, the discovery of the Dead Sea Scrolls beginning in 1947 would put such interests to rest. Like the Nash Papyrus, the great variety of Biblical manuscript types found in the caves near Qumran demonstrates that multiple versions of many Biblical texts could stand together side-by-side at Qumran, apparently presenting no problem to the Qumran scribes. The Pentateuchal manuscripts show a plethora of readings that may be traced to the proto-Masoretic Hebrew text, the 077Samaritan Hebrew text, the Hebrew text underlying the Greek Septuagint and others. The Nash Papyrus gave us but a taste of what was yet to come.

On Wednesday, February 18, 1948, John Trever, a fellow at the American School of Oriental Research in Jerusalem, answered a telephone call asking if the caller could bring by some ancient Hebrew manuscripts for him to look at. It was the last days of the British Mandate over Palestine, the Old City was ringed in barbed wire entanglements, and violence was rife. Trever was more concerned with the safety of the school and the people there than for old manuscripts. But, his curiosity piqued, he invited the caller, a Syrian Orthodox monk he knew named Butros Sowmy, to come […]

You have already read your free article for this month. Please join the BAS Library or become an All Access member of BAS to gain full access to this article and so much more.

Already a library member? Log in here.

Institution user? Log in with your IP address or Username

Footnotes

1.

YHWH, known as the tetragrammaton, is the four-letter personal name of the Israelite deity.

Endnotes

1.

John C. Trevor, The Dead Sea Scrolls—A Personal Account, a revised edition of Untold Story of Qumran, rev. ed. (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1979).

2.

Stanley A. Cooke, “A Pre-Massoretic Biblical Papyrus,” Proceedings of the Society of Biblical Archaeology 25 (1903), p. 34. See also F.C. Burkitt, “The Hebrew Papyrus of the Ten Commandments,” Jewish Quarterly Review 15 (1903), p. 392.

3.

William F. Albright, “A Biblical Fragment from the Maccabean Age: The Nash Papyrus,” Journal of Biblical Literature 56 (1937), p. 145.