The New ‘Ain Dara Temple: Closest Solomonic Parallel

A stunning parallel to Solomon’s Temple has been discovered in northern Syria.1 The temple at ‘Ain Dara has far more in common with the Jerusalem Temple described in the Book of Kings than any other known building. Yet the newly excavated temple has received almost no attention in this country, at least partially because the impressive excavation report, published a decade ago, was written in German by a Syrian scholar and archaeologist.2

For centuries, readers of the Bible have tried to envision Solomon’s glorious Jerusalem Temple, dedicated to the Israelite God, Yahweh. Nothing of Solomon’s Temple remains today; the Babylonians destroyed it utterly in 586 B.C.E. And the vivid Biblical descriptions are of limited help in reconstructing the building: Simply too many architectural terms have lost their meaning over the ensuing centuries, and too many details are absent from the text. Slowly, however, archaeologists are beginning to fill in the gaps in our knowledge of Solomon’s building project.

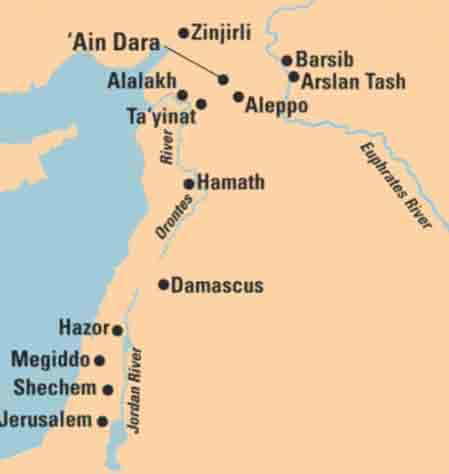

For years, pride of place went to the temple at Tell Ta‘yinat, also in northern Syria.a When it was discovered in 1936, the Tell Ta‘yinat temple, unlike the ‘Ain Dara temple, caused a sensation because of its similarities to Solomon’s Temple. Yet the ‘Ain Dara temple is closer in time to Solomon’s Temple by about a century (it is, in fact, essentially contemporaneous), is much closer in size to Solomon’s Temple than the smaller Tell Ta‘yinat temple, has several features found in Solomon’s Temple but not in the Tell Ta‘yinat temple, and is far better preserved than the Tell Ta‘yinat temple. In short, the ‘Ain Dara temple, which was excavated between 1980 and 1985, is the most significant parallel to Solomon’s Temple ever discovered.

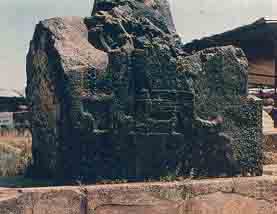

The ‘Ain Dara temple helps us better understand a number of enigmatic features in the Bible’s description of Solomon’s Temple. It also figures in the current debate, which has often raged in these pages,b as to the existence of David and Solomon and their United Monarchy in the tenth century B.C.E. And it is a magnificent structure in its own right. The ‘Ain Dara temple has beautifully preserved structural features, including limestone foundations and blocks of basalt. The building originally had a mudbrick superstructure—now lost—which may have been covered with wood paneling. The facade and interior walls are enlivened by hundreds of finely carved reliefs depicting lions, cherubim and other mythical creatures, mountain gods, palmettes and ornate geometric designs.

‘Ain Dara lies near the Syro-Turkish border, about 40 miles northwest of Aleppo and a little more than 50 miles northeast of Tell Ta‘yinat. The site is large, consisting of a main tell that rises 90 feet above the surrounding plain and an extensive lower city, which covers about 60 acres. ‘Ain Dara first attracted attention in 1955, with the chance discovery of a monumental basalt lion. Although the site was occupied from the Chalcolithic period (fourth millennium B.C.E.) to the Ottoman period (1517–1917 C.E.), the temple is undoubtedly the most spectacular discovery at the site. According to the excavator, Ali Abu Assaf, it existed for 550 years—from about 1300 B.C.E. to 740 B.C.E. He has identified three structural phases during this period.

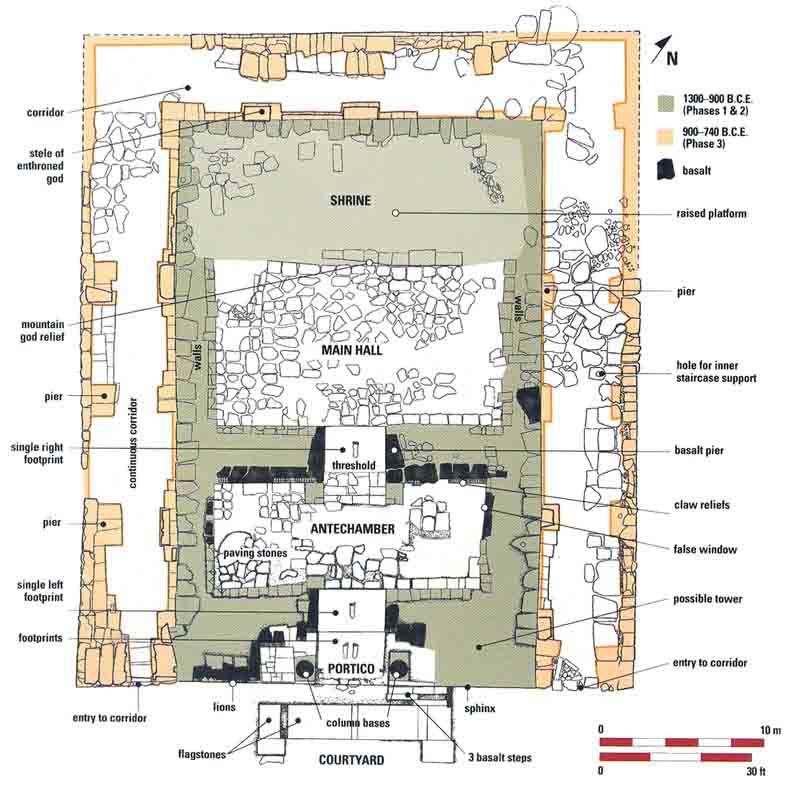

The building was constructed in Phase 1, which lasted from 1300 B.C.E. to 1000 B.C.E. Oriented towards the southeast, the temple is rectangular in plan, about 65 feet wide by 98 feet long. Built on a large raised platform, the temple consists essentially of three rooms: a niche-like portico, or porch; an antechamber (sometimes called the pronaos); and a main hall (cella, or naos), which housed the innermost shrine (in Biblical terms the debir, or holy of holies).

In Phase 2 (1000–900 B.C.E.), the period during which the Solomonic Temple was built, the ‘Ain Dara temple remained basically the same, except for the addition of basalt piers on the front facade of the building, immediately behind the columns, and in the entrances leading from the portico to the antechamber and from the antechamber to the main hall. Reliefs and a stele were also added to the shrine at the back of the main hall.

In Phase 3 (900–740 B.C.E.), an ambulatory, or hall, consisting of a series of side chambers was added on three sides of the building. The chambers were laid on the pre-existing temple platform, which extended beyond this new construction. The foundations of these chambers are not connected to the main part of the temple, indicating that they are a later addition.3

The dating of the two earlier phases was determined not by levels (stratigraphy) or by pottery (the excavation report does not record the stratigraphy and pottery of the temple), but by a comparison of the sculpture with that from other excavated sites.4

Like Solomon’s Temple, the ‘Ain Dara temple was approached by a courtyard paved with flagstones. A large chalkstone basin used for ceremonial purposes stood in this courtyard. (A large basin was also placed in the courtyard of the Jerusalem Temple [1 Kings 7:23–26].) At the far end of the open courtyard, the temple stood on a 2.5-foot-high platform made of rubble and limestone and lined with basalt blocks engraved with lions, sphinxes and other mythic creatures. A monumental staircase, flanked on each side by a sphinx and two lions, led up to the temple portico. The four basalt steps, only three of which survive, were decorated with a carved guilloche pattern, which consists of interlacing curved lines. The building itself was covered with rows of basalt reliefs of sphinxes, lions, mountain gods and large clawed creatures whose feet alone are preserved.5

Today, only the massive bases remain of the two columns that flanked the open entryway of the portico. These basalt columns, measuring about 3 feet in diameter, originally supported a roof that protected the portico. The portico entryway follows a common architectural plan known as distyle in antis; distyle (literally “two columns”) refers to the pillars that support the roof, and antis (from the Latin for “opposing”) refers to the extended arms of the building, which form the portico’s side walls and frame the entryway. At either side of this portico are wide square projections that may have supported towers or staircases. Wedged between these two projections, the entryway appears to be simply a niche in the facade of the building, rather than a separate room.

Sphinxes and colossal lions, carved into the interior walls of the portico, guard the passage into the antechamber. Two large slabs line the portico floor. On these floor slabs are carved gigantic human footprints—each more than 3 feet long. Two footprints appear on the first slab and one left footprint on the second, as if some giant had paused at the entryway before striding into the building. In ancient conception the temple was the abode of the god, which is why these have been interpreted as the footprints of the resident god—or goddess, as we shall see.

Based on the profusion of reliefs and sculptures of lions throughout the building, excavator Assaf attributes the temple to the goddess Ishtar, whose attribute is the lion; hence our use of the feminine.c While the footprints are those of a barefoot human, the deities in all the ‘Ain Dara temple reliefs are wearing shoes with curled-up toes. So readers must choose their own interpretation.

Large basalt orthostatsd engraved with flowery ribbon patterns lined the lower walls of the antechamber. Above them were carvings of immense clawed creatures. The identity of these animals is uncertain as only the claws have survived.

Three steps, decorated with a chainlike carving, lead up from the broad but shallow antechamber (it is 50 feet wide but only 25 feet deep) to the main hall, which forms an almost perfect square (54.5 by 55 feet). At the top of the stairs, a limestone slab serves as the threshold to the main chamber. Whoever was striding into the temple portico left a similarly enormous right footprint on this threshold. The distance between the two single footprints is about 30 feet. A stride of 30 feet would belong to a person (or goddess) about 65 feet tall.

A lion is carved in profile on each of the doorposts of the entryway to the main hall.

At the far end of the main hall is an elevated podium. This was the shrine, or holy of holies, the most sacred area in the temple. A ramp led up to the podium (or dais), which occupied the back third of the main hall. The rear wall of the chamber behind the podium has a shallow niche (adyton) in it, perhaps for a statue of the deity or a standing stone. Reliefs depicting various mountain gods lined the podium and the walls of the chamber. The mountain god, too, has a connection with the goddess Ishtar, who, in some incarnations, takes this deity as her lover. This lends further support to the excavator’s suggestion that the temple was dedicated to Ishtar.

A wooden screen—now lost—may have once separated the podium from the rest of the main hall: Several holes, or sockets, visible in the left wall (facing the podium) of the main hall and one in the right wall may have supported brackets for the screen.

Certainly one of the most splendid features of the ‘Ain Dara temple is the once multistoried hallway that enclosed the building on three sides during Phase 3. We conclude that it had at least one upper story—and maybe more—based on the thickness and number of large piers, set at regular intervals, which would have provided additional support for the wood and mudbrick construction of the upper floors. (The side chambers in Solomon’s Temple, incidentally, had three stories. which decreased in width from lowest to highest [1 Kings 6:5–10].)

These side chambers, which could be entered from either side of the portico, formed a continuous raised hallway that wrapped around three sides of the temple. Sculptures of lions guarded the entrances. Preserved to a height of nearly 5 feet, the corridor walls are lined with more than 80 panels carved with reliefs. In addition, 30 opposing stelae featuring a variety of scenes—a king on his throne, a palm tree, a standing god, offerings—stood on both sides of the corridor. (These are identified as migra‘ot, or piers, in 1 Kings 6:6; Ezekiel 41:6.) The exquisite workmanship in the side chambers indicates that they did not function merely as storage space. Indeed, the beautiful carvings indicate they may have had some ceremonial function. But what, precisely, would have been the function of these chambers? Again, readers must provide their own suggestions.

The exterior walls of these outer chambers were also decorated with lions and sphinxes, indicating the limited repertoire from which the carvers worked.

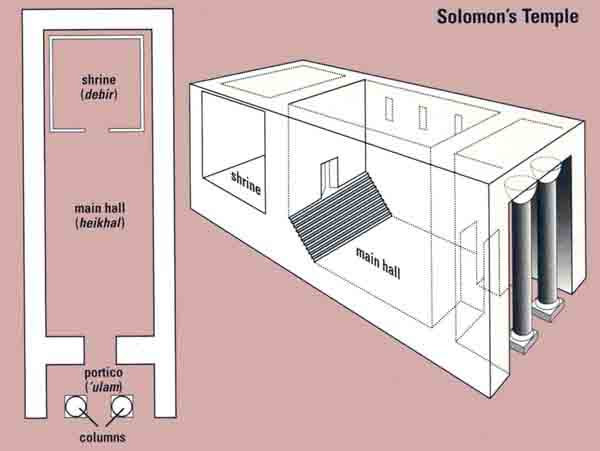

As already noted, the ‘Ain Dara temple shares many features with Solomon’s Temple in Jerusalem. Indeed, no other building excavated to date has as many features in common with the Biblical description of the Jerusalem Temple. Most basically, both have essentially the same three-division, long-room plan: At ‘Ain Dara, it is an entry portico, an antechamber and main chamber with screened-off shrine; in Solomon’s Temple, it is an entry portico (’ulam), main hall (heikhal) and shrine, or holy of holies (debir).e The only significant difference between the two is the inclusion of the antechamber in the ‘Ain Dara plan. With this exception the two plans are almost identical.

If the royal cubit used to build Solomon’s Temple was 52.5 centimeters, then the Jerusalem Temple measured approximately 120 feet by 34 feet. The ‘Ain Dara temple is 98 feet long by 65 wide (or 125 by 105 feet including the side chambers). (The Tell Ta‘yinat temple is only 81 feet long.) The ‘Ain Dara temple is thus not only the closest in date but also the closest in size of any temple in the Levant.

Like most ancient temples, both buildings stood at the highest elevation in the city. Both temples were built on a platform and had a courtyard in front with a monumental staircase (ma‘aleh, cf. Ezekiel 40:22) leading up to the temple.

In both cases the portico was narrower and shallower than the rooms of the temple. In both cases the portico was open on one side and had a roof supported by two pillars. (Unlike many reconstructions of Solomon’s Temple, the pillars Boaz and Jachin were not free-standing; indeed, the comparanda, such as the pillars at ‘Ain Dara, help to establish this. The position of the pillar bases at both ‘Ain Dara and Tell Ta‘yinat indicates they were load-bearing columns.)

In both cases spectacular reliefs decorated the walls, and the carvings in both temples share several motifs: The stylized floral designs and lily patterns, palmettes, winged creatures and lions of ‘Ain Dara may be compared with the “bas reliefs and engravings of cherubim, palm trees, and flower patterns, in the inner and outer rooms” of Solomon’s Temple (1 Kings 6:29).

The elevated podium at the back of the ‘Ain Dara temple, covering a third of the floor area of the main hall and set off from the forepart by a separate screen, is a commanding parallel for the Biblical holy of holies.

Without going into greater detail here, I have determined that the ‘Ain Dara temple shares 33 of the roughly 65 architectural elements mentioned in the Bible in connection with Solomon’s Temple.

Several additional features of the ‘Ain Dara temple help us to better understand aspects of the Biblical Temple as described in the Book of Kings. For example, the Biblical holy of holies is described as a wooden cube measuring 20 cubits on each side (1 Kings 6:20; Ezekiel 41:3–4) in a room 30 cubits high (1 Kings 6:2). It is unclear whether a 10-cubit stairway led up to the holy of holies or whether the shrine was on the same level as the main hall but had a lower ceiling and a space above. The ‘Ain Dara temple, as well as other comparanda, clearly indicates that a stairway would have led up to the holy of holies in Solomon’s Temple.

The outer ambulatory of ‘Ain Dara provides one of the site’s most dramatic contributions to our understanding of the Solomonic Temple. According to 1 Kings 6:5, the Biblical Temple was enclosed by something called sela‘ot, usually translated “side chambers.” But until the excavation of ‘Ain Dara, the term sela‘to defied a convincing explanation. That’s because before ‘Ain Dara, outer corridors were never attested in a second- or first-millennium B.C.E. temple. I believe that the hallways flanking the ‘Ain Dara temple can be none other than the sela‘ot of 1 Kings 6:5. These walkways at ‘Ain Dara are 18 feet wide, as are the Biblical side chambers (when the 5-cubit [about 8-foot] side chamber and 6-cubit [about 10-foot] outer wall of the Biblical Temple are added together). The ‘Ain Dara hallway is reached through doors on either side of the temple entrance, which brings to mind 1 Kings 6:8: “There was an entrance to the sela‘ot on the right side of the temple.”

On the basis of the side chambers at ‘Ain Dara and in Solomon’s Temple, it may be well to re-examine the evidence from other sites. I now suspect that side chambers were quite common. I have already identified seven temples, including Shechem, Megiddo and Alalakh, in which the foundations were wide enough to support multistoried side chambers built against the walls of the temple proper.

Another conundrum in the Biblical description of Solomon’s Temple: The Book of Kings refers to the Temple windows as shequfim ’atumîm (1 Kings 6:4). A footnote in the new Jewish Publication Society translation tells us the meaning is uncertain. The windows have variously been described as “recessed and latticed” or “framed and blocked.” Some scholars consider any attempt at translation to be an exercise in futility. Lawrence Stager of Harvard University has proposed that the phrase refers to windowlike frames that were stopped up with rubble—that is, faux (false) windows.6 ‘Ain Dara offers an intriguing parallel that allows us to take this idea a step further. At least two window frames were carved into the walls of the temple’s antechamber (see photo). Both windows have a recessed frame on each side; on top, the frame is also indented but is slightly arched. The upper half of each window is filled in with basalt carvings of horizontal rows of figure eights lying on their sides. The lower half is flat with a guilloche pattern running along the bottom. This, I believe, represents the kind of window lattice described in 1 Kings 6:4, thus providing a solution to a riddle that has eluded commentators for generations (compare Judges 5:28; Song of Songs 2:9 and Ben Sirach 42:11).

These faux windows would perhaps have been complemented by true windows close to the ceiling. One additional window frame, in this case an open one, appears in the northeast corner of the ‘Ain Dara temple.

The Bible describes “five-sided” (hamshit) and “four-sided” (rebi‘it) doors that led into the main hall and shrine of Solomon’s Temple (1 Kings 6:31, 33). These, too, have long puzzled commentators (and have led to a number of creative interpretations).7 In my view, these expressions refer not to the number of surfaces or sides in the door but the number of recesses in the door frame. Even the most basic door frames in the buildings of the ancient Near East often had a single recess, as the necropolis of Silwan in Jerusalem reveals.8 The doors in more luxurious structures—all over the Mediterranean world and in Mesopotamia—had several recesses in the frame. This is known as rabbeting; in a wooden construction, it is attained by fitting together several receding door frames. This can be replicated in stone on both doors and windows—as shown by the ‘Ain Dara temple and the description of Solomon’s Temple.

While the ‘Ain Dara temple makes its own singular contribution to our understanding of Solomon’s Temple, it must also be seen as part of a typology of ancient Near Eastern temples. Architecture, like ancient scripts and pottery, can be organized into chronological sequences and typologies. A century of archaeological research has unearthed a sizable corpus of parallel temples in the Levant that allow for increasingly refined reconstructions. In the years subsequent to the excavation of the Tell Ta‘yinat temple, others were discovered at such sites as Megiddo, Zinjirli, Alalakh and Hamath (see map). Each of these temples was associated with an adjacent palace, as, of course, was the case with Solomon’s Temple (2 Chronicles 2:1, 12). They date to various periods of the second and first millennia B.C.E. and conform very well to the Biblical description of Solomon’s regal-ritual center in Jerusalem.9

The assemblage of temples has continued to expand during the past two decades. Today we know of at least two dozen excavated temples that may be compared to Solomon’s Temple. Most of them are of the long-room type and come from the area north of the Israelite heartland. The Bible itself tells us that Solomon’s Temple design was mediated through Hiram of Tyre and other artisans from Phoenicia, the coastal region north of Israel (1 Kings 5, 7:13–37 [NJPS]).10 Amihai Mazar has called this temple plan the “symmetrical Syrian temple type.”11 Each has a courtyard in front, a portico, two rooms beyond and an elevated inner room, or holy of holies, at the rear, usually with a niche at the back. Each temple, of course, had its own configuration of secondary features, such as towers protruding from the facade, pillars flanking the entrance, and side chambers. Together they may therefore be regarded as hybrid temples that incorporate a mixture of indigenous and imported architectural forms appropriated for the local religious tradition of each city-state. The Jerusalem Temple includes features that belong to both Canaanite and North Syrian building traditions. Its various components reflect a combination of local traditions and cultural borrowing from farther afield. The influence of the Syrian long-room plan and the iconography of Phoenicia, Syria and Egypt are undeniable. But in the end, neither the Jerusalem Temple nor any of its closest parallels are traceable to a single, monolithic temple tradition.

Chronologically, the ‘Ain Dara temple forms a bridge in the temple sequence between the Late Bronze Age (1500–1200 B.C.E.) temple at Hazor (Area H) and the eighth-century B.C.E. Iron Age temple at Tell Ta‘yinat. The ‘Ain Dara temple corroborates the date of the Solomonic Temple to the early first millennium with a high degree of probability, regardless of the date assigned to the composition of the Biblical text. The Jerusalem Temple thus takes its place comfortably within the typology of Iron Age temples despite the dearth of architectural remains in Jerusalem. Such a broad-based typology is hard to overturn. As it is described in the Hebrew Bible, the Temple of Solomon is a typical hybrid temple belonging to the long-room Syrian type.

Simply put, the date, size and numerous features of the ‘Ain Dara temple provide new evidence that chronologically anchors the Temple of Solomon in the cultural traditions of the tenth century B.C.E. The ‘Ain Dara temple thus corroborates the traditional date of Solomon’s renowned shrine.

MLA Citation

Footnotes

See, for example, Volkmar Fritz, “What Can Archaeology Tell Us About Solomon’s Temple?” BAR 13:04.

See the following BAR articles: Philip Davies, “What Separates a Minimalist from a Maximalist? Not Much,” BAR 26:02, William Dever, “Save Us from Postmodern Malarkey,” BAR 26:02, and Amihai Mazar and John Camp, “Will Tel Rehov Save the United Monarchy?” BAR 26:02; Amnon Ben-Tor, “Excavating Hazor—Part I: Solomon’s City Rises from the Ashes,” BAR 25:02; “David’s Jerusalem: Fiction or Reality?”: Margreet Steiner, “It’s Not There—Archaeology Proves a Negative,” BAR 24:04, Jane Cahill, “It Is There: The Archaeological Evidence Proves It,” BAR 24:04, and Nadav Na’aman, “It Is There: Ancient Texts Prove It,” BAR 24:04; and Hershel Shanks, “Where Is the Tenth Century?” BAR 24:02.

In the accompanying article in this issue, Lawrence Stager identifies the deity of ‘Ain Dara as Ba‘al-Hadad.

Orthostats are large stones—sometimes undecorated, sometimes bearing complex designs—that are free-standing or that line the lower part of the walls of temples or public buildings. Orthostats carved in the shape of lions or other animals may serve as the base of the doorjambs flanking the entryway to such buildings.

The most detailed description of Solomon’s Temple appears in 1 Kings 6–7. The Book of Chronicles includes a parallel account (2 Chronicles 2–4), but this was written after the First Temple was destroyed. Other references are scattered throughout the Book of Kings and the prophecies of Jeremiah and Ezekiel (especially Ezekiel 40–46). For more on the Temple’s design, see the following articles: Victor Hurowitz, “Inside Solomon’s Temple,” Bible Review, April 1994; Volkmar Fritz, “What Can Archaeology Tell Us About Solomon’s Temple?” BAR 13:04; Ernest Marie-Laperrousaz, “King Solomon’s Wall Still Supports the Temple Mount,” BAR 13:03.

Endnotes

Portions of this article have been adapted from “The Temples of ‘Ain Dara and Jerusalem,” Text, Artifact, and Image: Revealing Ancient Israelite Religion, eds. Gary Beckman and Theodore Lewis (New Haven, CT: Yale Univ. Press, forthcoming). I would like to thank Anthony Appa for sharing with me his pictures of ‘Ain Dara and his experiences at the site. I am indebted to my mentor, Lawrence E. Stager, for many helpful comments.

Ali Abu Assaf, Der Tempel von ‘Ain Dara, Damaszener Forschungen 3 (Mainz: Philipp von Zabern, 1990).

Some scholars believe that the Jerusalem Temple was also built in several phases, one of which was the ambulatory; see D.W. Gooding, “An Impossible Shrine,” Vetus Testamentum Supplements 15 (1965), pp. 405–420.

These other sites are Carchemish, Zinjirli and other Neo-Hittite sites (see Abu Assaf, ‘Ain Dara, pp. 39–41). See more recently Abu Assaf, “Die Kleinfunde aus “‘An Dara,” Damaszener Mitteilungen 9 (1996), pp. 47–111.

Here and throughout the temple reliefs we find the “serpentine curve” pattern known from other finds in the Levant, including a basalt bowl from Hazor Temple H (see Yigael Yadin, Hazor III–IV [Jerusalem: Magnes, 1961], pl. 122) and most recently a tenth-century pottery vessel from Tel Rehov (see Amihai Mazar and John Camp, “Will Tel Rehov Save the United Monarchy?” BAR 26:02).

Lawrence E. Stager, “The Archaeology of the Family in Ancient Israel,” Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research 260 (1985), pp. 1–35; and “The Song of Deborah: Why Some Tribes Answered the Call and Others Did Not,” BAR 15:01.

David Ussishkin, The Village of Silwan: The Necropolis from the Period of the Judean Kingdom (Jerusalem: Israel Exploration Society, 1993), illus. 47, 94, 108.

The association of temple and palace in one building compound has been well attested in Mesopotamia and Egypt. It proved to be a popular layout in the Levant as well, as noted by Ussishkin (“Solomon and the Tayanat Temples,” Israel Exploration Journal (IEJ) 16 (1966), pp. 104–110; “Solomon’s Palace and Building 1723,” IEJ 16 [1966], pp. 174–186). In 1971 Theodor Busink published all known parallels in one monograph: Der Tempel von Jerusalem von Salomo bis Herodes: Eine archäologische-historische Studie unter Berücksichtigung des westsemitischen Tempelhaus, vol. 1, Der Tempel Salomos (Leiden: Brill, 1971). Despite the numerous similarities between the Biblical description and Canaanite and Syrian temples, he considered many of the features in the Jerusalem Temple to be Israelite innovations (p. 617)—a point on which we disagree.

Two seminal articles on this subject were written by David Ussishkin; see note 9. For earlier studies, see G. Ernest Wright, “The Significance of the Temple in the Ancient Near East,” part 3, “The Temple in Syria-Palestine,” Biblical Archaeologist (1944), pp. 65–77; Leroy Waterman, “The Damaged Blueprints of the Temple of Solomon,” Journal of Near Eastern Studies (1943), pp. 284–294.

Mazar’s typology is the most comprehensive proposed to date; see “Temples of the Middle and Late Bronze Ages and the Iron Age,” in The Architecture of Ancient Israel, ed. Aharon Kempinski and Ronny Reich (Jerusalem: Israel Exploration Society, 1992), pp. 161–187. See also Volkmar Fritz, “What Can Archaeology Tell Us About Solomon’s Temple?” BAR 13:04. The temples range in date from the third to first millennium B.C.E. and include Munbaqa, Emar, Ebla D, Mari, Chuera, Hayyat, Kittan, ‘Ain Dara, Tayinat, Ebla B1, N, Hazor Area A, Hazor Area H, Dab‘a, Alalakh I, Hamath, Shechem, Megiddo, Haror, Alalakh VII, IV, Byblos II, Carchemish, Lachish P, Beth-Shean VI and the temenos at Dan.