For Paul, as well as for the Gospels as they have come down to us, the most meaningful moments of Jesus’ life were his crucifixion and—beyond that—his resurrection. It is not difficult to understand, however, why contemporary cartoons and comic strips look elsewhere in the New Testament for their material. For popular entertainment, cartoonists, from traditional to avant-garde, have fruitfully and creatively sought their inspiration in two other events: the nativity and the Sermon on the Mount.

Modern critical scholars have noted significant differences, perhaps even contradictions, between the nativity accounts in Matthew and Luke, often constructing elaborate hypotheses to account for these variations. On the other hand, the lay public apparently has little difficulty combining and conflating the two stories into one continuous, if crowded scene, such as we find in Christmas plays.

It is to this latter group that cartoonists appeal. In fact, the cartoonists’ portrayal of the nativity often centers on the Christmas play, that annual tragicomedy of pageantry that has become a yuletide staple for American Christians.

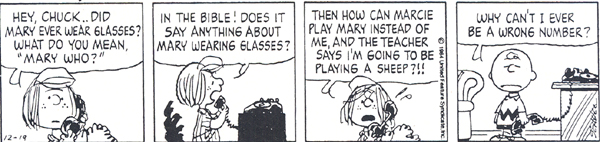

No one has better captured the contradictory emotions of children preparing for such a (dis) play than Charles Schulz. During several Decembers in the past decade, Schulz has devoted a week or so to the ongoing struggles of his diminutive characters participating in the Christian pageant. For one Christmas, readers of “Peanuts” were confronted, as were its characters, with the weighty question: “Did Mary ever wear glasses?”

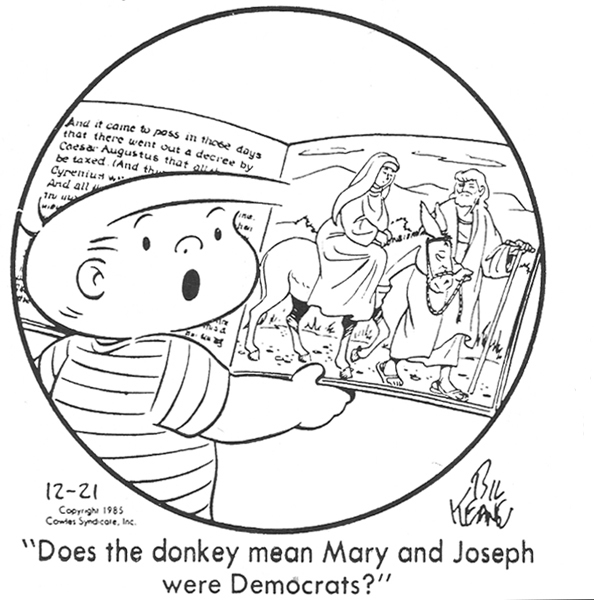

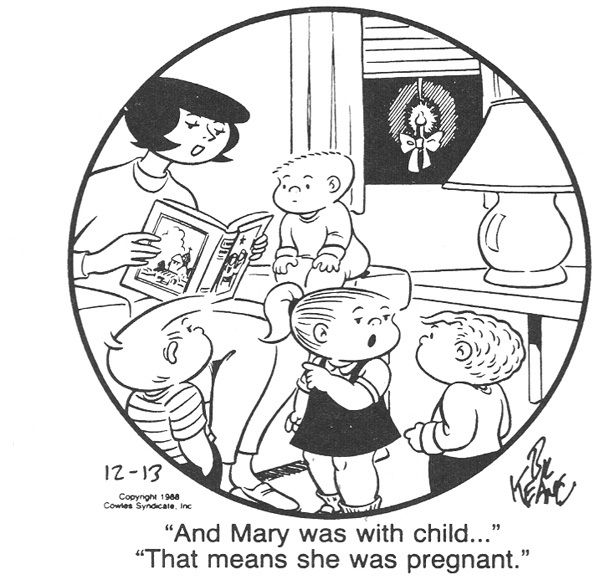

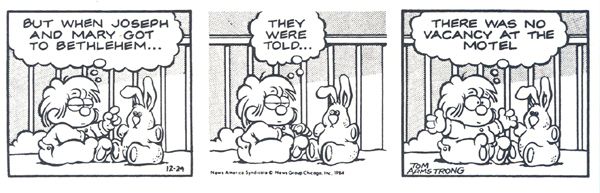

Other cartoonists also bring the nativity into the modern world to make a humorous or, less frequently, a starkly serious statement. Characteristic of the former are Season’s Greetings from comic strips as diverse as “Family Circus” (see photos of “Family Circus”) and “Marvin” (see photo of “Marvin”). In a more serious vein, an “Arnold” strip on December 25, 1984, highlighted the contrast between the brightness of biblical hopes and the tarnished reality of today’s troubled world.

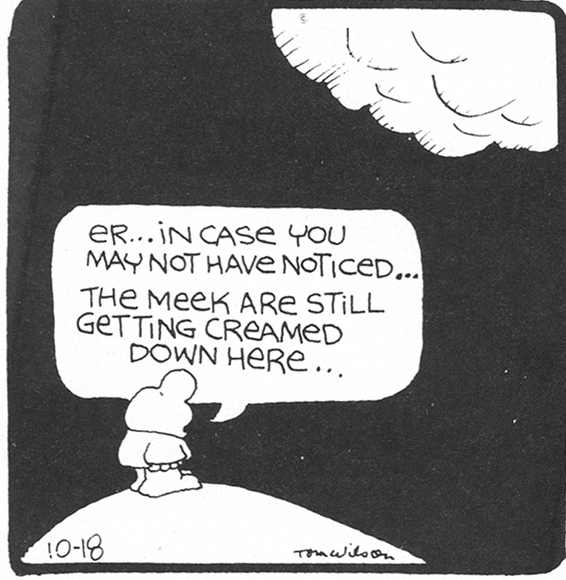

The words of Jesus as reported in the Sermon on the Mount (Matthew 5–7) are among the most vivid and frequently quoted in the entire New Testament (some of these sayings are also contained, though in less memorable form, in Luke’s Sermon on the Plain [Luke 6:20–49]). Modern scholarship has amassed a great deal of evidence that this sermon is not something that was actually delivered on a single occasion, but rather is an artful collection of Jesus’ teachings from several places and times. Some of these sayings have assumed the status of secular axioms. Comic strip readers may not even realize that biblical phrases are being invoked. Other readers will make the biblical connection when they read of the meek inheriting the earth, or of turning the other cheek, even if they can’t identify the book that is being quoted or whether it is in the Old or New Testament.

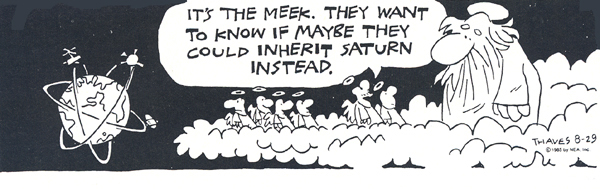

No phrase is more often cited in more different cartoon situations than the third beatitude from the Sermon on the Mount (Matthew 5:5): “Blessed are the meek, for they shall inherit the earth.” Incidentally, the cartoonists almost always stick with this King James rendering even though numerous modern translations differ somewhat. The Revised English Bible, for example, renders this verse: “Blessed are the gentle; they shall have the earth for their possession.” Not only is this less elegant, but it won’t work in many of the cartoons. Try, for example, substituting the “gentle” for the “meek” in the two examples from “Frank and Ernest” (see photos of “Frank and Ernest”).

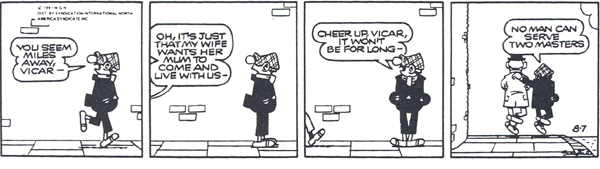

I have found eight other phrases from the Sermon on the Mount alluded to in cartoons. Among the most easily recognizable are “turning the other cheek” (Matthew 5:39), “serving two masters” (Matthew 6:24) and “seek/find, ask/receive” (Matthew 7:7–8). “Andy Capp” provides an example of one of these (below).

Otherwise, only a handful of Gospel sayings have been included in comic strips. Three of them are quite familiar: “Let the little children come” (Matthew 19:13); “Physician, heal thyself” (Luke 4:23); and “He that is without sin among you, let him first cast a stone” (John 8:7). The one I have chosen to illustrate here is from “Family Circus,” in which the cartoonist pictures the kingdom of heaven from a child’s perspective (see photo of “Family Circus”).

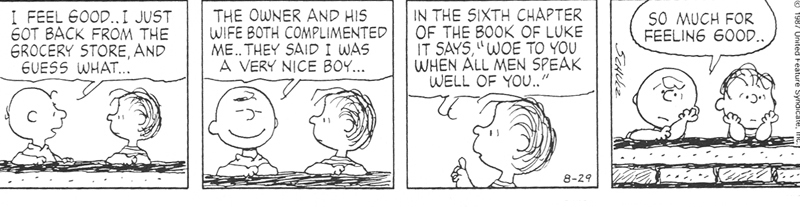

As he does with the Old Testament, Charles Schulz considerably expands the number and nature of his New Testament references by literally citing chapter and verse for passages that even longtime Bible readers might well find a little obscure. He recognizes that it is unlikely his readers will be able to identify the phrase, “Woe when men speak well … ” (see above). It comes from Luke 6:26, a part of the Sermon on the Plain. The Sermon on the Plain contains not only beatitudes that begin “blessed … ” (and differ somewhat from the beatitudes in the Sermon on the Mount), but also woes that begin “woe to you … ”

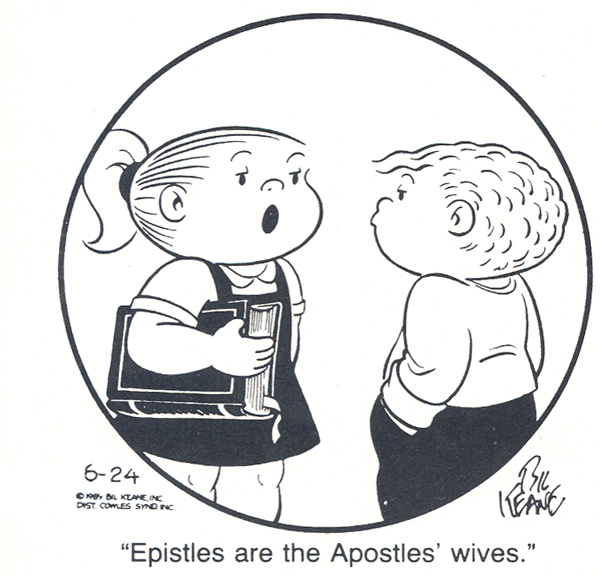

Outside of the Gospels, I have found approximately 15 other New Testament passages cited or alluded to in cartoons and comic strips. For example, the canine cartoon character Fred Basset quotes Acts 20:35 (“It is more blessed to give than to receive”) and manages to transform what might otherwise appear to be an act of cowardice (or self-preservation) into biblically mandated generosity (see above).

Obviously the Bible has excited the imagination of cartoonists and delighted millions of their readers. To paraphrase the pious editor of the Book of Ecclesiastes, in the traditional language of the King James version: “Of making many cartoons there is no end.”