064

In December 1993, when Pierre Bikai, director of the the American Center of Oriental Research (ACOR) in Amman, Jordan, and his team discovered a cache of burnt papyrus scrolls in a Byzantine church in Petra, he wanted to avoid the kind of publication scandals that surrounded the Dead Sea Scrolls. He decided the best way to do this was with a written contract drafted by a lawyer, spelling out in detail the rights and responsibilities of all parties involved—ACOR (the excavator), Jordan’s Department of Antiquities and the papyrologists who would conserve and decipher the fragile texts.

The contract Bikai used could well serve as a model for the publication rights to ancient inscriptions. It could even be adapted to provide for the publication of the excavation itself. Even though some may not agree with every provision in the contract, it can still serve as a checklist of the issues that must be covered in any publication agreement.

The recitations at the beginning of the contract provide that “all parties recognize the right of the scholarly community and the general public to have access to and information about the papyri, their contents, and the impact of their contents upon the course of history.”

The 152 papyri in the sixth-century A.D. hoard from Petra were divided between two papyrologists, Ludwig Koenen of the University of Michigan and Jaakko Frösén of the University of Finland.

Under the terms of the contract, each scholar has been given five years to complete his work and is required to submit an annual progress report. An extension of up to three years can be requested, but it must be approved by an editorial board. If deadlines are not met, ACOR can reassign the publication rights—and publish photographs of the scrolls.

Even before publication, any scholar can apply for access to an unpublished scroll to the appropriate editor, who has 30 days to decide whether to grant or deny the request. If the editor chooses to deny access, then the other parties to the contract will decide by majority vote whether access is to be denied or granted.

The contract states that “the scrolls and the original 065contents thereof are in the public domain”; nevertheless, any photograph, transcription or reconstruction remains the property of the papyrologist. Unfortunately, this creates, in effect, a monopoly on the scrolls and their contents. Once the scrolls are published, anyone should be allowed to reproduce the photos, transcripts and reconstructions. No one else will be able to devote the time, money and energy to creating these from the original scrolls. To say that the scrolls and their contents are in the public domain but the photographs, transcriptions and reconstructions belong to individual scholars is to give with one hand and take away with the other.

Museums, incidentally, are doing the same thing with the artifacts they display. They used to allow photographers to take pictures of these artifacts; therefore, photographs were readily available in a competitive market. More recently, museums have begun to allow only their staff photographers to take pictures, refusing permission to everyone else. The result: If you want a picture of an artifact, there is only one source, the museum, that can decide to whom and under what conditions access will be allowed, and can take as much time and charge as much money as it wants—in effect, creating a monopoly.

Apart from this flaw, the contract for the Petra papyri appears both reasonable and complete. The provisions were worked out by archaeologist Patricia M. Bikai, Pierre’s wife, with the counsel of Henry Christensen III, of the law firm of Sullivan and Cromwell, in New York. Copies of the contract may be requested by writing to Dr. Patricia Bikai, ACOR, P.O. Box 2470, Amman, Jordan.

The papyri themselves, in the words of Pierre Bikai, bring sixth-century A.D. Petra back to life. Ironically, the scrolls were preserved by a fire. Because they are small (about the size of a piece of stationery) and tightly rolled, the fire carbonized the papyrus on which they were written instead of consuming it. The dull black ink is still legible on the charred, shiny black backround.

Because of the scrolls’ fragile condition and the thinness of the papyrus (a tenth of a millimeter), it proved impossible to unroll the scrolls; thus each layer had to be lifted one at a time, in strips, which were then placed on acid-free tissue paper. Using special methods of overexposure, it was possible to photograph them in black and white. Even the black-on-black is, in most cases, surprisingly legible in the lab, particularly under special light.

The conservation work, performed in the ACOR lab, began in September 1994 and was completed in May 1995. Now the contents are being transcribed, translated and interpreted.

Most of the scrolls concern wills and inherited property. One deals with the settlement of a dispute over water rights. Quite a few involve real estate rights; others deal with loans and marriages.

Most of the scrolls are written in Greek. A couple of lines are in Latin, and some Nabatean names appear. The documents, covering a 54-year period between 528 and 582 A.D., during the reign of the emperor Justinian and his successors, can be accurately dated based on four different kinds of internal dates. They include the regnal year of the emperor, the year of certain tax periods and the year of the era of the Province of Arabia or the era of the Province of Gaza.

From the historian’s viewpoint, the sixth century has been almost a blank page at Petra; indeed, scholars once thought that it had been destroyed in the mid-sixth century A.D. It now appears that Petra was still an important Byzantine regional administrative center at that time. The new scrolls provide an unusually rich store of material on the social and economic life of the city and its rural hinterland.

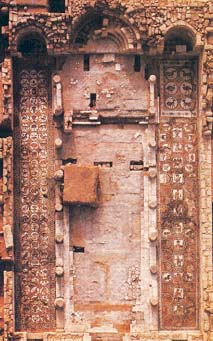

The church where the scrolls were found is a magnificent tri-apsidal structure with some of the finest mosaics ever discovered in a country extraordinarily rich in mosaics. The church measures 85 by 50 feet; some of its walls are still preserved up to 10 feet above floor level. An atrium, a partially open, stone-paved courtyard, originally stood in front of the west entrance of the church. The excavators believe that much of the material in the church—such as its capitals, door jambs and reliefs—came from nearby Nabatean and Roman ruins. The church itself is a relatively new discovery, uncovered in 1990 by the late Kenneth W. Russell. Bikai assumed leadership of the excavation upon Russell’s death in 1992 and struck paydirt the folowing year with the discovery of the scrolls.

In December 1993, when Pierre Bikai, director of the the American Center of Oriental Research (ACOR) in Amman, Jordan, and his team discovered a cache of burnt papyrus scrolls in a Byzantine church in Petra, he wanted to avoid the kind of publication scandals that surrounded the Dead Sea Scrolls. He decided the best way to do this was with a written contract drafted by a lawyer, spelling out in detail the rights and responsibilities of all parties involved—ACOR (the excavator), Jordan’s Department of Antiquities and the papyrologists who would conserve and decipher the fragile texts. The contract Bikai […]

You have already read your free article for this month. Please join the BAS Library or become an All Access member of BAS to gain full access to this article and so much more.

Already a library member? Log in here.

Institution user? Log in with your IP address or Username