The Philistines and the Dothans: An Archaeological Romance, Part 1

An interview with Moshe and Trude Dothan

022

They are the first family of Israeli archeology. Trude and Moshe Dothan each have more than four decades of experience in the field, having excavated such major sites as Hazor, Hammath Tiberius, Nahariya, Deir el-Balah, Akko, Ashdid and Ekron. In this first installment of a two-part interview with BAR editor Hershel Shanks, the Dothans reminisce about how they met; share their recollections of such towering figures as William Foxwell Albright, Yigael Yadin, Roland de Vaux and Kathleen Kenyon; and describe the emergence of modern Israeli archaeology—a field of study they very much helped to shape.

Hershel Shanks: Something is very unusual about you two. I know a few other couples who are both scholars. I know Ruth and David Amiran [archaeologist and geographer, respectively], and I know Haim and Miriam Tadmor [Assyriologist and Israel Museum curator, respectively], but the two of you are the only husband-and-wife team in Israel who are both archaeologists.

Trude Dothan: I think we were the first, but now I don’t know how many couples have resulted from excavating together. We may be the only two archaeologists who are directing excavations and are professors in universities. But there are other couples, some among my students. There is nothing more romantic than being on a dig, you know. You can divorce or get married or have an affair. It can happen. But anyhow, many couples do come out of excavations.

HS: How long have you been married?

023

Trude: My chronology is very bad. I never remember.

Moshe Dothan: Forty-three years.

HS: Was it a romance on a dig?

Moshe: No. We met in 1946. I was in the army, first in the British army, then in the Israeli army. I spent more or less five years in both armies before I started to study at Hebrew University.

Trude: I was also in the army, but very low. I was in Jerusalem during our War of Independence [1948].

Moshe: I was not directly her commander. She was in a special group connected with intelligence. We met each other in Jerusalem. We got married in 1950.

HS: So you had a long courtship?

Trude: There were other men in between [laughter]. This is getting very personal.

HS: I don’t want to get too personal.

Trude: It’s all right. It’s nice.

HS: Had you both been studying archaeology?

Trude and Moshe: Yes.

Trude: And I think Moshe read with me [William Foxwell] Albright’s excavation report on Tell Beit Mirsim. It’s not exactly romantic.

Moshe: We got along slowly but surely.

Trude: When I left the army and Moshe left the army, that’s when we got married.

HS: When was your first child born?

Moshe: He was born in 1954.

Trude: When he was a year old, two years old, three years old, we took him to the dig at Hazor, where we were both area supervisors. He was Dennis the Menace.

HS: Was Yigael Yadin the director of the dig?

Moshe: Yes.

HS: Was he a great director?

Moshe: Very good. We learned a lot. We also did a lot. Trude’s area was one of the most important—the area of the temples. Mine included some very important stratification.

Trude: Then Moshe went on to become deputy director of the Department of Antiquities [now the Israel Antiquities Authority].

HS: Do you think the fact that you’ve never actually dug in the same square together saved your marriage?

Trude: [Laughter.] That’s a very good question. In a way, it did. People used to ask me, “How can you go to a dig—a woman with children, a family?”

It’s not easy. It’s almost impossible to have a family and do a dig together. In Hazor, I took Dani with me. It’s not the easiest thing to have a little boy with you. The whole group there were the baby-sitters. Even today, Dani 024is kind of a legend. He would sit with us in the afternoon when we were reading the pottery. We said “EB” [Early Bronze], “MB” [Middle Bronze], “LB” [Late Bronze], “Byz” [Byzantine] as each sherd was identified. When I got back to Jerusalem, Dani’s kindergarten teacher called and asked me, “What kind of song is Dani singing: EB, MB, LB, Byz?”

All: [Laughter.]

Trude: Yadin was very nice to children. He thought Dani was a very smart little boy and Dani was on very good terms with him. It was in a way fun to have Dani along, but it was not the easiest thing. I’m not sure I would recommend it. Now it’s different. You have a whole entourage and you can do it more easily.

HS: Some couples say that they have to leave business at work and not let it intrude into their personal lives. Can you ever leave business at work if you both come home and you’re both archaeologists?

Moshe: We seldom talk about our projects.

Trude: You see, we already disagree.

All: [Laughter.]

Moshe: Very seldom. [To Trude:] Maybe for you it is too much.

Trude: Our neighbor, a very good friend who stayed with us during the war [the Scud attacks during the 1991 Gulf War], says that when she comes here and sees that you can cut the air … that there’s a terrible fight going on and she knows we are living somewhere in the 13th century B.C. There’s no ideal life and we try to talk about other things. But we do talk about archaeology.

HS: I remember once the two of you were in my office in Washington, and you got into an argument about the Philistines.

Moshe: Yes. I remember, but I don’t remember what it was about.

Trude: But, you see, we survived it.

All: [Laughter.]

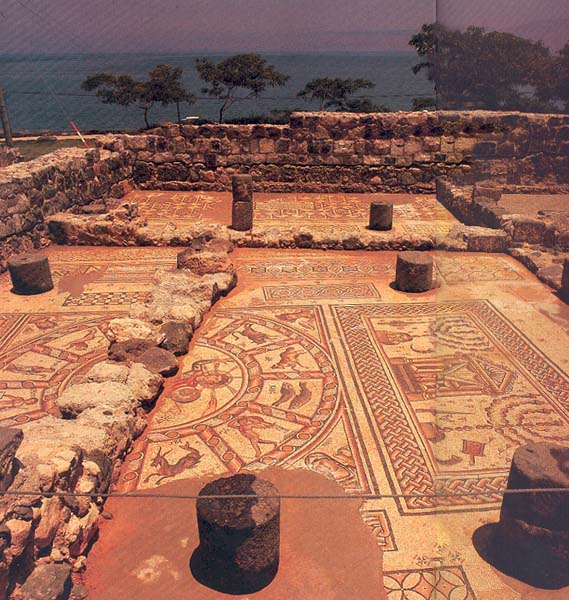

HS: Moshe, you are unusual in another way. Your archaeological interests are extremely broad. You dug in Ashdod. You excavated in Akko. You directed the excavation of a synagogue on the Sea of Galilee, at Hammath Tiberias. You go from Early Bronze to Byzantine.

Moshe: Yes. You are right. But you are wrong in one thing. I started in Chalcolithic [c. 4000 B.C.]. That was my Ph.D. dissertation—1,000 years before Early Bronze. I go more or less up to the tenth century A.D.

HS: Trude, in your generation, there are some extremely distinguished women archaeologists in Israel: Ruth Amiran, Claire Epstein and, of course, you. Other women who are not field archaeologists deal with archaeological materials, like Miriam Tadmor and Ruth Hestrin. Was there a greater openness to women in those pioneer days?

Trude: Each of these women has her own individual background. Take Claire Epstein. She did a lot on her own. She got her Ph.D. at Oxford. She is a kibbutznik. She is her own one-man expedition. By force of her total dedication, she did the one thing she wanted to do: work on bichrome ware and the Chalcolithic period. It’s fantastic what she did. She is a one-man team. She really belongs to the British generation. She is unique.

HS: Different from Kathleen Kenyon?

Trude: Kenyon belonged to the establishment. There is difference. Claire did things on her own.

HS: You’ve had your career at the [Hebrew] University.

Trude: But I was the only one for years and years and years. As a woman professor, there was nobody.

HS: Was that because of gender discrimination?

Trude: No. Absolutely not. Perhaps I advanced more slowly to full professor than the men in my department, but that was my fault because I had other responsibilities.

It is very difficult if you want to be totally dedicated to your profession, but you also want to build a home, you want to raise a family, you want to have children. In a way, I am not a feminist, but I believe women should get the same pay. Moshe helped me all the way. But still, when the children are small, you have to stay home. Many times the younger generation, my students, ask what they should do. I tell them, the one thing is, don’t stop. The moment you stop and think that in ten years you will come back, you’re lost.

But if a woman wants to live a life that has all the facets, then she will not advance as quickly. It’s not easy to be a field archaeologist and to do these other things. But there are women who do it.

In the new generation, we’ll have more women archaeologists. There is far more equality now. The husbands are ready to take over and be baby-sitters. But this question is a very, very personal one, and I don’t think you can generalize.

HS: When you started in archaeology, how did the work differ from today?

025

Moshe: We were few, and this is why we had to do so much. I remember in the beginning, in the mid-1950s, I had two people for excavation in the entire Department of Antiquities. Today, there are at least 100.

HS: How many people would be involved in an excavation in those days?

Moshe: Usually one, two or three professionals—at a maximum. As to workers, it depends on which dig. In a small dig—in Nahariya, for instance—I had maybe 20 people altogether, including workers. In Ashdod there were 60 or 70 people.

HS: You used paid workers in the beginning, didn’t you?

Moshe: Both [paid workers and volunteers].

Trude: New immigrants from Persia and Europe worked on the digs. The government paid them because they didn’t have any other work. This is really what enabled us to work on such a big scale. You had immigrants from Persia. You had immigrants from Iraq, from Europe. Nobody could talk to anybody else. It was really a melting pot.

HS: Did either of you know Albright?

Moshe: Yes, of course.

HS: What were your impressions of Albright?

Moshe: He was a fantastic man. I wouldn’t say he was a genius, because a genius is something very, very special but he was very close to it. Even today, there is no one to match him at judging what is important and what is not important—in the Bible, in history and in the Near East generally. He knew so much. His methods are still used today.

HS: What are your recollections of Albright, Trude?

Trude: I remember him well. We met him first in Israel when he came to the archaeological congress in Beer-Sheva. He spoke Hebrew. We were amazed. To go out with him was really fantastic. He knew every piece of land. He was very interested in sharing information. He would let you know when you were wrong, which is also great. Now people frequently point out in articles that he often changed his mind. Well, it is great to know how to change your mind.

HS: Bill Dever has criticized Albright for being too Biblical.a Do you see any trends in the relationship of archaeologists to the Bible?

Trude: There are people who are afraid of saying they are Biblical archaeologists. I can’t say that I am a Biblical archaeologist, but I definitely turn to the Bible. I think it’s wonderful that we have the possibility of putting the material into a framework and relating it to the Bible. We don’t have to take the Bible at face value. I am the handmaiden of Biblical scholars. I see myself first of all as an archaeologist. But definitely I am not detached from the background. If you use the Bible properly as a source, and you don’t follow it blindly, why should you be so worried about it?

What I’m doing is Mediterranean archaeology in the Biblical period. I go out of Israel to the whole Mediterranean. So I can say that I am a Mediterranean archaeologist with a background in the land of the Bible, or whatever you call Israel. It’s all semantics. I think you need every source you can get. We are very fortunate that we have the Bible in this period. That is why we are different from archaeologists who don’t have this background.

HS: Moshe, do you sense that in younger archaeologists, either in America or in Israel, that they are happier when an interpretation goes against the Bible than when it supports the Biblical text?

026

Moshe: Whether for or against, they must relate to the Bible. I place much more emphasis on the Biblical connotations than Trude. You have to be very careful before concluding that something is different from what the Bible says. You have to look first to see if there is some interpretation of the written words that fits what you find. The Bible is really almost our only source. If it weren’t for the Bible, there are so many places we wouldn’t even be able to identify. There is so much we wouldn’t be able to understand. Of course, not everything written in the Bible—in historical geography, for instance—is correct. Names change. People make mistakes, and so on. But, after all, this is really our only important source. I’m not talking as a Zionist. I’m talking only as a Biblical archaeologist. What would we know about the Philistines if it weren’t for the Bible?

Trude: I agree with what Moshe said. Who’s afraid of Biblical archaeology? But there is this trend away from it. I think it swings, and it will swing back. In the end, I feel it will find its right place. For an American archaeologist, it’s dangerous to go to Greece with Homer in one hand and a spade in the other. You shouldn’t get carried away by it, but, of course, Homer is in the back of the mind of the Greek archaeologist.

HS: Today, Israeli archaeologists dominate the scene in Israel. There are some Americans and a few from other countries, but mostly they are Israelis. In the past, the foreign schools were much more significant, especially the British and the French schools. They were both giants—Pere Roland de Vaux of the French school and Kathleen Kenyon of the British school. Let’s talk first about de Vaux.

Trude: He was fascinating. He was one of the most charming men I ever met. I first met him when I was a student. He came to visit our excavation. I had no idea who he was. But here I saw this very good-looking man in a white robe. When we went to eat, he pulled my chair out, put my chair in. I was not used to these Frenchmen. I had never been treated like that; the sabras [native-born Israelis] in Israel are not exactly perfect gentlemen. Then he told jokes. He had a fantastic sense of humor. I don’t know if it’s true, but it was said he was a member of the Comédie Française. Later, he had a terrible accident when he fell from a horse. He was quite disfigured.

After the Six-Day War [in June 1967], we flew to the United States with him; we had such fun. He had a beard and he wore a dark jacket. He told us that the last time he flew it was on a Friday and since he looked like a priest they wouldn’t give him meat. This time, too, it was a Friday. But this time they thought he was a rabbi, so they brought him kosher food. It was so funny. He was a man of culture, very liberal, a wonderful scholar. His book on Israelite institutions is really a great book.b I used it just the other day. His excavation at Tell el-Far’ah (North), unfortunately, was never published; he only published in fragments and sections.

HS: There has been no final publication of his excavation at Qumran, either.

Trude: True.

HS: What about Kathleen Kenyon?

Moshe: She was completely different.

Trude: As a student I went to London to the Institute of Archaeology, the British school. In the basement, I was going through [Sir Flinders] Petrie’s material from Tell el-Far’ah (South). I 027was really afraid of her.

HS: She was a big woman, wasn’t she?

Trude: Yes. At the agora in Greece, we had met some American women archaeologists—kind of tough women—and I thought, “Should I become an archaeologist if you have to be like this?” I was really worried. Then I was told, “Wait till you meet Kathleen Kenyon. Then you will really worry.”

I met her that time in England and I must say she was very nice, but I wouldn’t go up to her after a lecture and ask her questions.

Later, after the Six-Day War, I thought that now that Jerusalem was open we would be able to talk to Kenyon. We would exchange ideas and laugh. I was really extremely naive. The last thing Kenyon wanted was for Israelis to be part of Jerusalem. She really represented the end of the empire, the grande dame. We were natives. More than that, we made it impossible for her to go into the Old City, as she loved to do, as the great English matron who was in charge of their life.

HS: Why was it impossible for her to go into the Old City?

Trude: She could go, but not with the same status. With the Arabs on her excavation, she was the grande dame. She was their friend, but from above. She liked that kind of relationship. With us, it was totally different.

Once she went with Yadin on a tour of Megiddo. A group went on a bus. She told us this story later. When she got out, the driver approached her and said, “Ah, Miss Kenyon, I’m so glad to meet you. I have read all your books.” And he started asking her about the stratigraphy of Megiddo. Then he took her in the bus all around Megiddo and showed her all the problems of strata 5A and 6B. She couldn’t get over that—that he was a bus driver.

The last time I met her was very sad. It was in Tübingen [Germany], a big meeting to celebrate the 500th anniversary of the university. They invited people from all over—England, Germany, France, Canada, Israel. They gave Kenyon an honorary doctorate. She got up and gave a lecture on Jerusalem. That was after our Israeli excavations in Jerusalem. She behaved as if nothing had happened. It was terrible. It was really pathetic. We sat there and we didn’t know what to do. A. D. Tushinghamc also spoke as if nothing had happened after Kenyon. And that was one of the problems. Kenyon did not relate to other excavations.

The last time I saw her, it was a year before she died. She had on a very shiny party dress and was chain-smoking. She was a fascinating person. It was very sad that she couldn’t admit that maybe something happened to change things. It was too painful for her to do it.

In a way it is very sad because Kenyon dug very meticulously in very difficult circumstances. She did pioneer work in Jericho. You can disagree with her conclusions. The pathetic thing is that she was extremely careful. She dug deep sections. But in Jerusalem, she dug only fragments and tried to build up the whole picture from those fragments—and then she was proved wrong. That is the sad part of it. She lived long enough to know that there were later excavations, but she could not relate to them. That is really the tragedy. She just couldn’t take it. She couldn’t face the changeover with Israel coming in, and then she couldn’t take the changes that came with the new Israeli excavations.

HS: She was well known as an anti-Zionist.

Trude: She didn’t love Israel.

HS: Do you think that affected her interpretations?

Trude: I don’t know.

Moshe: Whenever there was the possibility, she tried to …

Trude: … minimize.

Moshe: … minimize the number of Israelites, and so on. If it was possible to interpret something negatively or to say there were fewer people or that something was not important, she would do it. Perhaps it worked unconsciously, but it worked. This was especially so with her last work in Jerusalem.

HS: What was [Hebrew University professor Benjamin] Mazar like in the early days?

Trude: Mazar hasn’t changed. He even looks the same—only an older version. Mazar has been very important for me—and for many of us. I always wanted to be an archaeologist. I was attracted by the adventure of it. My father was involved with a lot of archaeologists and used to go on trips with them.

At first I studied with [E. L.] Sukenik [Yigael Yadin’s father], who didn’t teach us much. He was not very interested in his students. And then there was [L. A.] Mayer. I enjoyed his classes because I always liked art. So I enjoyed his classes because we studied mostly manuscripts and illuminations. But the one who really taught us archaeology was Mazar even though he didn’t teach archaeology. He taught historical geography, but we went with him on surveys. I was never really a student of Mazar’s, but I became part of the Mazar group. It was really a very special group. There were [Haim] Tadmor, [Avraham] Malamat and at that time there were many more, but quite a number of his outstanding students were killed in the War of 029Independence [in 1947–1948]. Mazar really created interest, and he had the knowledge. He brought things alive. He was a great teacher. He was interested in his students, and he really discussed things with us. You know, he takes you by the arm and shakes you. Then he asks you about this and that, and then he tells you what he thinks. He really brought things alive on these surveys and outings we had with him. This was, for me, terribly important. At that time, digging was not part of the curriculum. I ran away from the university to dig with Mazar at Beth Yerah; I was almost thrown out of the university because of that. After that, I went with him to Ein Gedi while I was still in the army. And then I went to Tell Qasile with him. It was really Mazar who was teaching archaeology.

HS: He was never a great field archaeologist?

Trude: He had this thing which is terribly important—the vision. He would take with him people who could do it—like Munya Dunayevsky, an architect who died; Munya was a great stratigrapher. But Mazar’s intuition was unbelievable. He knew what he was looking for. In those days it was a very, very small team—Miriam Tadmor, myself, Moshe came for a time. Every afternoon we would go out, and the way Mazar brought things to life was unbelievable. He was not interested at all in the details. But he did bring everything together. He had the ability to organize. This is a great part of archaeology. You have to be an organizer if you want to direct a dig. He had this ability, besides being a historian and geographer and an archaeologist. He would not go and dig himself, but he would take the team and, in a way, show us what to look for. This was very, very important.

It’s sad because his excavations have really not been published enough. That is one of the problems. But he was a great teacher.

HS: I thought about that just yesterday when I was at the excavation of the southern wall of the Temple Mount. We’ll never know the details of what was excavated there.

Trude: I think it was very well recorded. They had very good architects and a very good recording system. I hope that it will be published. There is no doubt a problem there. Many other big excavations have this problem. We know that.

HS: What is the problem? Moshe, you have been involved in big excavations.

Moshe: You must know Mazar really well to judge him. No one went on digs with Sukenik, who was the head of the department. [Nahman] Avigad went, but he was Sukenik’s assistant. But students didn’t go on digs. And here you have a man [Mazar] who was not an archaeologist—who was teaching history and historical geography—and he makes the digs and he takes the students and gives them all this, all the background for archaeology. If it weren’t for Mazar, nobody would have done it. Mazar was not educated as an archaeologist. 030Now the question of writing all these reports, you need people of ability to write the reports. If it were history, Mazar could do it immediately but for archaeology, he needs help. I am sure in a few years the problem [of the Jerusalem excavation report] will come before a committee of the Antiquities Authority and a solution will be found.

Trude: You ask a hard question and I think it’s very difficult to answer. Pioneers like Mazar did an enormous amount. You can’t judge them. It’s very sad that things have not been published. In Yadin’s case, most of his excavations are being published after his death.

Moshe: If Mazar had someone who could help—like Avigad who helped Mazar in Beth Shearim …

Trude: It is a difficult question. And it’s not only Jerusalem. It’s an overall problem with excavations that have not been published. It’s very easy to blame the people who were carried away with digging, who had busy periods—like Mazar, when he was president of the [Hebrew] University. But he instigated many things that happened in archaeology.

There is this problem, however, of not publishing. No doubt, this is weighing on him. I do hope that he will still be able to get it done with the help of people around him. This is terribly important. It’s not easy to dig, but it’s very hard to publish. We must find an easier way to do it than the way it is done now. What we should do is dig and publish immediately a preliminary report, but it’s easier said than done. We are all carried away by digging.

HS: Do you think the profession has really faced the problem of publication? It harries every archaeologist. There’s almost no archaeologist who isn’t found wanting on the score of publication.

Trude: We should have a meeting on how to publish. We were thinking about that for next year—to get all of us together and find a way. There is no one standard. Every dig is different. Every excavator is different. We all want to put everything into the report. Maybe that’s the wrong way. We don’t know where to stop, to say that’s it. But it’s a very serious problem.

HS: Moshe, you haven’t dug in Ashdod for how many years?

Moshe: Since 1972. I am now almost finished with the final report. I have published four volumes and have now finished volumes five and six. There will be one more—volume seven, the last one. I have a few other sites. Nahariya is very important. I have the material.d I hope in three years the most important things will be ready for publication.

But I haven’t left a single excavation without some report—sometimes only 20 pages, sometimes 10 pages. I hope in a few years everything that is worthwhile will be published.

HS: You have another volume to do on Hammath Tiberias?

Moshe: Yes, that manuscript is already finished.

HS: Do you think that archaeologists should start new digs without publishing their old digs? Do you think there should be a limit on that?

Moshe: Of course there should be. Now we can put limits on it. But when I was in the Department of Antiquities, we had only two or three people and many excavations. I excavated places with three or four people that needed 20 or 25 people. I did it myself with few volunteers. These were mostly rescue excavations. This was how most of the excavations were started. For example, take Hammath Tiberias. I had just finished working with Mazar and [Avraham] Biran at Ein Gev and the next day I had to go to excavate Hammath Tiberias.

HS: Why was Hammath Tiberias a rescue operation?

Moshe: Because the people who had the hot baths wanted to enlarge them. They had started to work.

Special police had to be called in. They asked me to excavate it because they needed this place. The people who owned the hot baths even financed the dig.

HS: But they never got their site, did they? [Laughter by all.] [It remains an archaeological park.]

Moshe: No.

Trude: There is no justice.

Moshe: But I was able to save part of the city wall and the gate to Hammath Tiberias. This is how we worked. Immediately afterwards I had to start in Ashdod. When I got there, part of it was already gone.

HS: Where did it go?

Moshe: People were taking it as a material for fill. Today it is much better, you can’t even compare. Now you work and you publish; there are enough people. Today, it is completely different.

HS: How has excavating changed in your digging experience?

Trude: Now, whether in a big dig or in a small dig, it’s far more complex and far more interdisciplinary. That’s good. But, on the other hand, you should not be overawed by the sciences. We archaeologists are still on the border of the humanities. Take a dig that I am involved in now—Ekron, which is a very well-planned dig.e It is a joint Israeli and American dig. My colleague Sy [Seymour] Gitin plans very carefully and he does a wonderful job. We get all the scientists together. This is a standard thing to do. The big problem really is how to utilize the material, how to publish it and how not to be overwhelmed by it. In Deir el-Balah [an excavation Trude Dothan directed in the Gaza Strip], we have appendixes and appendixes [in the published report]f from all these interdisciplinary colleagues—written very nicely.

031

But then the question is how to get the overall picture. Techniques are important. If you are a good archaeologist you use these techniques; you hold your team together; you know what your aim is; you record well. It’s important to have a good system, but there is nothing more important than to have the eye—to see, to be in close contact in the field. It’s also important to really know what the important things are and what the secondary things are. Otherwise, you’ll be overwhelmed. You want to know how people lived, what arms they used, what sanctuaries they worshiped in. It’s like an enormous jigsaw puzzle.

Coming in Part II—The Dothans describe how, together, they have revealed the world of the Philistines (“The Philistines and the Dothans—An Archaeological Romance, Part 2,” BAR 19:05).

They are the first family of Israeli archeology. Trude and Moshe Dothan each have more than four decades of experience in the field, having excavated such major sites as Hazor, Hammath Tiberius, Nahariya, Deir el-Balah, Akko, Ashdid and Ekron. In this first installment of a two-part interview with BAR editor Hershel Shanks, the Dothans reminisce about how they met; share their recollections of such towering figures as William Foxwell Albright, Yigael Yadin, Roland de Vaux and Kathleen Kenyon; and describe the emergence of modern Israeli archaeology—a field of study they very much helped to shape. Hershel Shanks: Something is […]

You have already read your free article for this month. Please join the BAS Library or become an All Access member of BAS to gain full access to this article and so much more.

Already a library member? Log in here.

Institution user? Log in with your IP address or Username

Footnotes

See Hershel Shanks, “Should the Term ‘Biblical Archaeology’ Be Abandoned?” BAR 07:03, and William G. Dever, “On Abandoning the Term ‘Biblical Archaeology,’”, Queries & Comments, BAR 07:05.

Roland de Vaux Ancient Israel—Its life and Institutions ( London: Darton, Longman and Todd. Ltd.), 1961.

Principal author of volume 1 of the final report on Kenyon’s Excavations in Jerusalem 1961–1967 (Royal Ontario Museum, 1985; reviewed in BAR 13:03). Tushingham was chief archaeologist of the Royal Ontario Museum.

Volume five of the Ashdod final report is in press and volume six is in progress; the Nahariya report is in progress.—Ed.

See Trude Dothan and Seymour Gitin, “Ekron of the Philistines,’ BAR 16:01 and “Ekron of the Philistines, Part II,” BAR 16:02.