026

027

I have spent the better part of my professional life studying the lowly Roman amphora—a two-handled clay jar used by the Canaanites, Phoenicians, Greeks and Romans to ship goods. What would Harvard professor Charles Eliot Norton, who founded the Archaeological Institute of America in 1879, have thought about my archaeological tastes? Norton wanted archaeology, especially Greek archaeology, to uplift Americans morally and aesthetically through the study of elegant ancient artifacts. Yet, paradoxically, near the top of his headstone in the Mount Auburn Cemetery in Cambridge, 028Massachusetts, is a small amphora carved in relief.

My relationship with this unassuming vessel began almost by accident. In 1951, soon after receiving my Ph.D. in Greek and Latin, I found myself at the American School of Classical Studies at Athens—a Homer specialist with nothing to do that couldn’t be done better in America. Virginia Grace, the late authority on Greek amphoras, suggested that I spend the year studying the Roman variety in her workrooms at the Agora Excavations. At the time, hardly anyone was working on Roman amphoras, though a few European scholars had published studies decades earlier. Little did I know that these simple jars would provide essential evidence for mapping out trading routes of Roman merchants, and thus would force us to rewrite Roman economic history.

For some years now, Marxist ancient historians have denied that there was any profit-oriented trade in Greco-Roman antiquity. Why? Because Karl Marx wrote in Das Kapital (1867) that “the capitalistic era dates from the 16th century.” Now things are changing, and the Marxists are adopting the advice of a federal judge in the Microsoft case: “When you are riding a dead horse, the best strategy is to dismount.” Free of theoretical blinders, we can now see that the Romans of the late republic and early empire did engage in real, and extensive, trade. Indeed, it seems as though a Roman merchant would have gone anywhere—scaled up the frozen north, scampered through the exotic East—to make a deal. This was a form of capitalism. And we know about it largely because of the commonplace amphora.

From about the third century B.C. to the fifth century A.D., energetic Roman traders sailed huge cargo ships to the ends of the known earth, as we can tell from shipwrecks and excavations. They ventured out into the Atlantic, at least to the west coast of Scotland and to the Canary Islands; they traveled by river deep into western and eastern Europe; and they sailed to India and, probably, beyond.

This was large-scale trade by sea and river, not the more limited land trade along such routes as the Silk Road, over which small objects were transported to and from Rome. Land trade was much more 029expensive than seaborne trade, largely because the bulky Roman ships could carry large, heavy cargoes.

Contrary to much that has been written, Roman traders preceded the flag. Military conquests did not keep up with trade, and there is increasing evidence that even Roman conquests had motives that were in part economic: keeping open trade routes, safeguarding ports, securing new markets, ridding the seas of pirates. The sea, though dangerous, presented vigorous and successful traders with huge profits, which were critically important to the Roman Republic and later to the Roman Empire.

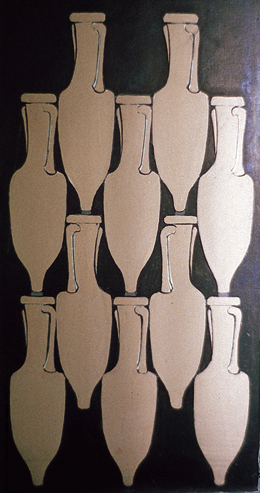

The capacious holds of Roman cargo ships were filled in a herringbone pattern with hundreds, sometimes thousands, of heavy, thick-walled, six-gallon clay containers roughly 3 feet in height, called amphoras. Amphi means “on both sides” in Greek, and phero means “carry,” so an amphora was something carried by handles on both sides. This common shipping vessel also had a “third handle,” a long toe or foot, which enabled a stevedore to hoist the heavy container onto his shoulder or to roll it along the ground by rotating the two handles. The toe also supported the amphora when it was propped against a wall, rather like the end-pin of a cello or a double bass. In the holds of ships, one amphora’s toe fitted snugly between the handles of amphoras in the layer below, preventing the immense load from shifting. So the amphora shape was practical—and not unattractive; in fact, the 19th-century German Romantic philosopher Arthur Schopenhauer referred to the amphora as the most perfect shape invented by mankind—but he was probably thinking of the more elegant bronze or decorated clay amphoras, not of “pigs,” as we called commercial amphoras unearthed in the Agora Excavations in Athens.

Amphoras were the standard shipping containers for both Greeks and Romans, as they were for earlier peoples like the Canaanites in the second millennium B.C. and the Phoenicians in the early first millennium B.C.a Roman traders exported and imported grain in sacks, but they filled amphoras with perishable products like olive oil, wine, fruit, fish sauce (garum), tuna, olives, honey, lard, eggs and spring water, and also with inedible commodities such as paint, unguents, pitch and cosmetics. The shapes of the amphoras indicated what was in them: tall and slim for wine, globular or baggy-bellied for olive oil, hollow-toed for fish sauce, and pig-shaped for fruits. After arriving at their destination, amphoras were reused as storage containers. The Romans had very few storage facilities in their homes or shops, as the excavations at Pompeii and Herculaneum indicate, so amphoras served to store and keep cool (as thick clay walls do) whatever one wished to put in them: wine, oil or vegetables—though jars that had contained smelly fish sauce might not have been the best choice as secondary containers.

030

Perhaps the chief secondary use of amphoras was in construction. Broken amphora fragments were cemented together and used in walls, foundations, piers and breakwaters. The Romans also discovered that empty amphoras, when embedded in ceilings or placed under theater stages or speaker’s platforms, improved acoustics. Amphoras were also reused as ballistic missiles, children’s coffins, ash urns and decoration for tombs (see photo of olive oil amphora from Protestant Cemetary in Rome). Their similarity to the human figure had connotations of immortality—as is suggested by amphoras used as ancient cinerary urns and amphoras placed in ancient graveyards. Even today, tombs in the Protestant Cemetery in Rome are decorated with amphoras—as is Charles Eliot Norton’s gravestone.

Shipping amphoras are generally the chief finds on once-inhabited Roman sites, accounting by some estimates for 80 percent of the material, not including the amphoras reused in construction. And the percentage rises even higher under water, since most Roman leviathans that plowed the deep—the ancient equivalents of modern oil tankers—had cargoes of hundreds, even thousands, of amphoras. When they were wrecked, their cargoes came to rest on the sea bottom.

In the not too distant past, the Greeks and Phoenicians were identified as sailors, whereas the Romans, before Hollywood decided that they spent all their time in brutality and self-indulgence, were thought to have been primarily farmers. Roman trade was believed to have taken place on the famous network of Roman roads, all of which led to Rome. But that was before 1943, when Jacques-Yves Cousteau’s co-invention of the aqualung launched the era of underwater archaeology. In 1950, Cousteau bought the boat Calypso, a former British minesweeper; two years later he agreed to help the French archaeologist Fernand Benoît explore a wreck filled with hundreds of amphoras that had foundered on the Grand Congloué rock off Marseilles. At the time, Virginia Grace and I were working at the Agora Excavations (which have provided precise contextual information allowing us to date most types of Roman amphora). We were consulted by the French excavators, who thought they had found a large Greek ship from the third century B.C. But we knew that the amphoras were Roman and that they dated from two distinctly different periods, about 200 B.C. and about 100 B.C.; therefore, the find must have consisted of two different ships. At dangerous headlands, multiple wrecks often occur over time. That’s what happened at the Grand Congloué.

The Grand Congloué wrecks, along with other evidence from beneath the deep blue sea, have filled in our knowledge of Roman enterprise. After Rome wrested control of the Mediterranean from the Carthaginians at the end of the First Punic War in 241 B.C., she began to package her surplus agricultural products in amphoras, load them on ships and sell them in western Mediterranean markets that had been served by the Etruscans and later by Phoenician Carthage. The earliest known Roman amphoras, dating to the last half of the third century B.C., were used for wine; they were somewhat smaller (about 2.5 feet high) than their later counterparts (generally over 3 feet high). These 031so-called Roman Greco-Italic amphoras took their shape from fourth- and early third-century B.C. amphoras that probably originated in the Greek colonies of Sicily and southern Italy, or perhaps in Greece itself.

We even know, from studies of the clay, where early Greco-Italic amphoras were manufactured: in the area of Campania close to Mount Vesuvius; in Etruria, about 200 miles north of Pompeii; in far southeastern Italy; and in the fertile lands and islands around the northern coast of the Adriatic Sea. Each of these regions also had a principal export harbor: Pompeii, in Campania; Cosa, in Etruria; Brindisi, on the heel of Italy’s boot; and Aquileia, in the northern Adriatic. Only the ports at Aquileia and Cosa have been thoroughly explored, though some work has also been done at Pompeii.

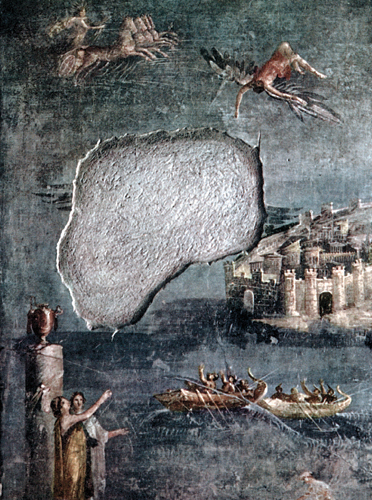

The Roman geographer Strabo (c. 64 B.C.–21 A.D.) tells us in his Geography (5.4.8) that Pompeii was an export-import harbor in his day. Although only a fraction of the silted-up Port of Pompeii has been explored, we now know that it was located on the southeast side of the city, outside the Sarno Gate.b (The painting shown above, which depicts the fall of Icarus and was discovered in the House of Sacerdos Amandus, may well show this part of Pompeii.)

Excavations at Pompeii have uncovered a large porticoed building of the early first century B.C. outside the Sarno Gate. Among the finds in the building were dozens of wax tablets recording loans to individuals of Puteoli, the large import harbor serving Rome, a short distance up the coast. And just a few years ago, the Pompeii excavations uncovered Greco-Italic wine amphoras made of local clay. This archaeological evidence suggests that Pompeii served not only as an amphora-manufacturing center but also as a major port—just as Strabo said.

For years I have maintained (though most scholars in Europe disagreed with me) that Pompeii was a manufacturing and distribution center for wine in the Roman Republic and for garum (fish sauce) in the Roman Empire, right up until the city was destroyed by the eruption of Mount Vesuvius in 79 A.D. My evidence consisted of amphora stamps with the names of known Pompeians—stamps found not 032only at Pompeii but at sites to which the amphoras were exported, such as Alexandria and Athens. Pompeii had sent wine out over the Mediterranean, I concluded, as early as the last quarter of the third century B.C.

In this early period, two Pompeian names stand out. Trebius Loisios, whose family owned a brick factory, is mentioned on numerous Greco-Italic amphora stamps found throughout the Mediterranean from Mallorca, an island off the east coast of Spain, to Alexandria. And the Ovius family of Pompeii, also owners of a pottery factory, shipped stamped Greco-Italic amphoras as far afield as Macedonia and Alexandria.

The volcanic soil around Mount Vesuvius produced—and continues to produce—several varieties of very good table-grade wine. But the wine shipped abroad by Pompeians in Greco-Italic amphoras was probably imitation Koan wine. On the Aegean islands of Kos, Rhodes and Knidos, vintners made their wines with seawater, presumably as a preservative. The wine from Kos was famous for its medicinal qualities. The Roman statesman Cato the Elder (234–149 B.C.) even included a recipe for Koan wine in his book De Agri Cultura (chapter 112). The jars shown in the so-called “Cupids as Wine Dealers” painting (see photo of “Cupids as Wine Dealers” fresco), in Pompeii’s House of the Vettii, closely resemble the distinctive shape of amphoras known to have been made at Kos (a later and larger vessel than the Greco-Italic type). The Koan jar shape also seems to have been used in Italy to deceive Italian buyers into thinking that they were buying the genuine wine of Kos. Pompeii’s winesellers even tried to conceal the fact that their amphoras were made of the coarse, dark-red Vesuvian clay—rather than the fine, pale clay of Kos—by painting the vessels with a greenish surface wash suggesting the greenish wash on the surfaces of real Koan amphoras.

The larger, pseudo-Koan amphoras replaced the Greco-Italic amphoras in the last half of the second century B.C. Many of these pseudo-Koan vessels are stamped with trademarks naming known Pompeians, among them Publius Sulla, the nephew of the Roman dictator Lucius Sulla (c. 138–78 B.C.). During this period, Roman trade expanded significantly: Rome now controlled Greece, and she had defeated and destroyed Carthage in the Third Punic War (146 B.C.). Amphoras, too, got larger and took on different shapes, as new Roman markets developed, new goods began to be traded and new producers entered the picture.

During the first century B.C. and the first century A.D., India was one of the chief markets for the large pseudo-Koan Pompeian jars, and especially for the 033amphoras of Kos itself (now Roman Kos). The wealthy Tamil kings of southern India imported wine from Rhodes and Knidos—but they especially favored Koan wine, both the real stuff from Kos itself and the supposed Koan wine from Pompeii.c

Did the Roman ships that reached the Bay of Bengal stop there? Or did they go farther? Chinese ambassadors, we know, visited Rome, and Rome certainly had Chinese silk. But expensive Chinese goods could have been acquired in India or Alexandria, or they could have been carried along the Silk Road. Further excavations, particularly the kind of deep-water surveys being conducted by Robert Ballard, who discovered the Titanic in 1985, will likely expand these horizons in the future.

The Port of Cosa (not to be confused with the island of Kos), an extensively studied site on the Tyrrhenian coast about halfway between Rome and Pisa, provides a similar picture of a thriving export industry. By the last years of the third century B.C., Cosa was producing Greco-Italic amphoras looking very much like the ones from Pompeii. The Greco-Italic shape probably spread up the coast from Pompeii to Cosa. But Cosa’s amphoras were made of distinctively Cosan clay, quite unlike that of Pompeii. When they were stamped or marked, it was usually with the letters “SES” or “SEST,” the stamps of Cosa’s Sestius family (see the second sidebar to this article). These Sestius amphoras have been found throughout the western Mediterranean. One of the Grand Congloué wrecks, on which Jacques Cousteau worked in the 1950s, contained 1,500 amphoras, from the late second or early first century B.C., bearing the “SES” stamp. In 1997, at the Skerki Bank, a deep-water site between Sardinia and Tunisia, Anna Marguerite McCann and Robert Ballard found a Greco-Italic amphora with the Sestius stamp at the base of the handle. Unstamped Greco-Italics made of Cosa clay, one of them painted with the “SES” trademark, have been found at ancient Manching (north of Munich) on the Danube. They must have been shipped up the Rhone and then perhaps over canals (traces of which have been discovered) to the Rhine and the Danube.

As at Pompeii, in the last half of the second century B.C. the Cosa amphoras grew larger. These later amphoras1 were regularly stamped on the rim with the letters “SES.” They can be dated, on the basis of contexts at the Athenian Agora, to the late second and early first centuries B.C. They were used to ship wine made in the Cosa area.

The Sestius factory also manufactured and exported garum, though in differently shaped jars.2 This shape was soon being copied in Spain, as shown by the recent discovery at Cadiz, in southern Spain, of a factory that made garum amphoras in this same shape. The Sestius factory must have been huge to produce the shipment of amphoras found on the upper Grand Congloué wreck. This family was also the chief wine-producer in Italy during the late republic, and it maintained a virtual monopoly over exports of wine to the thirsty Celts in Gaul.

If the Sestius family dominated the export industry at Cosa, Pompeii seems to have had several smaller factories that worked together competitively but harmoniously. This was also true at Brindisi, on the heel of the Italian boot. Through the first half of the second century B.C., the chief export from Brindisi was wine. But by the late second century B.C., Brindisi had turned to the export of olive oil, which was in great demand in Egypt. Venafran olives, which Pliny the Elder (23–79 A.D.) praised as the most famous in the world, were probably brought to amphora factories near Brindisi, where they were pressed into oil, bottled in globular jars3 and shipped abroad, particularly to Alexandria.

Mass production, diversification, competition—all these features of a vigorous capitalism also prevailed at Aquileia, the only harbor for sea-going ships in the northern Adriatic. From Aquileia, rich Istrian olive oil was shipped chiefly to the island of Delos and to Athens—in amphoras of a distinctive shape4 that were mass-produced by a number of different factories.

Did some central Roman authority decree that Brindisi should send its oil chiefly to Alexandria, while Aquileia shipped its oil 034to Delos and Athens—just as Cosa sent its wine mainly to Gaul, while Pompeii exported imitation Koan wine chiefly to the East? What part did protectionism play in the distribution of wine and oil during the republic? Although this aspect of Roman economic history is far from certain, my feeling is that while production was primarily private, there was very likely state interference in the distribution process.

During the Roman Empire, the provinces began to supplant Italy as the major suppliers of the world’s markets. But what did it matter, since the whole Mediterranean was controlled by Rome? Olive oil and garum from Spain, wine from Gaul and olive oil from Africa found their way to India. Spain dominated the olive oil scene until the third century A.D.—as we know from the hill of broken amphoras making up Monte Testaccio in Rome—and Roman Spanish traders reached as far as Scotland and India. African olive oil was dominant from the third to the fifth centuries A.D. French wine, which became hugely popular in the early empire, gave way to wine industries in Africa: in Mauretania Caesariensis, in modern Algeria; and Mauretania, in modern Morocco.

Just how far did the Romans go? Is there a Roman ship off the Azores, as some say? Are there thousands of Phoenician and Roman amphora fragments on Salt Island in the Cape Verdes, as reported by the underwater salvor Robert Marx? Is the “Rio Wreck,” at the bottom of Guanabara Bay near Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, a Roman ship that in ancient times was blown off course?

Twice a year London’s Sunday Times phones me to ask if I know anything more about the Rio Wreck. The highly publicized amphoras Robert Marx found in the ship are in fact similar in shape to jars produced in kilns at Kouass, on the west coast of Morocco. The Rio jars look to be late versions of those jars, perhaps datable to the third century A.D. I have 035a large piece of one of the Rio jars, but no labs I have consulted have any clay similar in composition. So the edges of the earth for Rome, beyond India and Scotland and eastern Europe, remain shrouded in mystery.

This article is adapted from an address presented as the Ninth Phyllis Williams Lehmann Lecture, an annual lectureship established by the Western Massachusetts Society of the Archaeological Institute of America to commemorate Phyllis Lehmann’s achievements in the fields of archaeology and art history.

I have spent the better part of my professional life studying the lowly Roman amphora—a two-handled clay jar used by the Canaanites, Phoenicians, Greeks and Romans to ship goods. What would Harvard professor Charles Eliot Norton, who founded the Archaeological Institute of America in 1879, have thought about my archaeological tastes? Norton wanted archaeology, especially Greek archaeology, to uplift Americans morally and aesthetically through the study of elegant ancient artifacts. Yet, paradoxically, near the top of his headstone in the Mount Auburn Cemetery in Cambridge, 028Massachusetts, is a small amphora carved in relief. My relationship with this unassuming […]

You have already read your free article for this month. Please join the BAS Library or become an All Access member of BAS to gain full access to this article and so much more.

Already a library member? Log in here.

Institution user? Log in with your IP address or Username

Footnotes

For example, in June 1999 the underwater explorer Robert Ballard and Harvard archaeologist Lawrence Stager discovered two eighth-century B.C. Phoenician ships lying beneath 1,500 feet of water 30 miles off the Israeli coastal city of Ashkelon. The main cargo of the ships consisted of amphoras, many in pristine condition.

The Pompeianist Wilhelmina Jashemski, from whom I have learned so much, pointed out to me a lararium painting at Pompeii (House I.xiv.6/7) showing the river god Sarnus pouring water into the Sarnus River, while agricultural produce is being loaded into a small boat.

Endnotes

Type 4a; see Elizabeth Lyding Will, “The Roman Amphoras,” in Anna Marguerite McCann et al., eds., The Roman Port and Fishery of Cosa (Princeton, NJ: Princeton Univ. Press, 1987), pp. 182–201.

Type 11a; see Will, “Relazione mutue tra le anfore romane,” in Anfore Romane e storia economica: un decennio di ricerche (Rome: Ecole Française de Rome, 1989), p. 301; see also Will, “Shipping Amphoras as Indicators of Economic Romanization in Athens,” Michael C. Hoff and Susan I. Rotroff, eds., The Romanization of Athens (Oxford: Oxbow Books, 1997), p. 24. Such factories had been reported in 1883 by the German scholar Theodor Mommsen, but their locations had been forgotten. In 1969, after a difficult search, I was lucky enough to be the first to discover such an amphora. Archaeologists have since located many other factories, even as far west as Metaponto, not far from the modern Italian city of Taranto.