The Saga of ‘The Gospel of Jesus’ Wife’

055

Although he is not an archaeologist, Canadian/Israeli TV journalist and producer Simcha Jacobovici (pronounced Yacobovitch) has made some remarkable archaeological discoveries.

For example, the first plague: When pharaoh refused to let the people go, Moses held out his rod, and the waters of Egypt, including the Nile and even the waters in vessels, turned into blood (Exodus 17:14–21). Simcha discovered how it was done: Earthquakes triggered gas leaks that did it; Simcha found a lake that turned reddish brown from such a gas leak.

Before the Israelites left Egypt, they “borrowed” silver and gold from the Egyptians and then took it with them (Exodus 11:2–3; 12:35–36). Simcha has found some of this—in Greece. As Simcha discovered, some of the Israelite slaves did not go to the Promised Land but boarded ships and sailed to Greece. There some of the gold that the Israelites brought with them from Egypt turned up in the tombs of Mycenae.

And this is only the beginning. Simcha’s discoveries relating to Jesus and early Christianity are breathtaking. Let’s begin with the nails that were used in Jesus’ crucifixion; he found them in the lab of an Israeli academic at Tel Aviv University.

Simcha has also discovered the true tomb of Jesus and much of his family.

In another Jerusalem tomb, Simcha found one of the earliest Christian symbols—Jonah emerging from the whale after three days, just like the resurrection of Jesus from the tomb after three days. Elsewhere was an engraving of the earliest Christian symbol—a fish.

Most recently, Simcha has been arguing that Jesus was married to Mary Magdalene and together they had a son. “The proof of the historical marriage is … overwhelming,” he says.

Let me say it straight out: Simcha is a friend of mine. I like him. He’s very smart. And I admit that I’m not enough 056 of a scholar to refute his claims. But I think it fair to say that the reaction of the academy to Simcha’s claims, by and large, has been a thunderous silence. Simcha is simply not taken seriously. The major academic reaction, where there has been one, is a rolling of the eyes. Harvard’s Lawrence Stager has characterized Simcha’s archaeology as “fantastic archaeology.” And BAR does not publish Simcha’s far-fetched claims. Simcha has his own reaction to the academic response—or non-response—to his claims, this one regarding the fish: It has been “largely ignored because … [it] upsets too many theological apple carts.” As his astounding finds pile up, he admits he is met “only [with] more derision.”

I recite all this in contrast to Karen King’s announcement that in an ancient Coptic gospel fragment Jesus, speaking in the first person, refers to “my wife.” At first glance this would seem to be of a piece with Simcha’s “discoveries.” In fact, it is far different.

In the first place, King is a professor at Harvard Divinity School; she holds the oldest endowed academic chair in the United States. More important, her conclusions are backed up by formidable scholarly research.

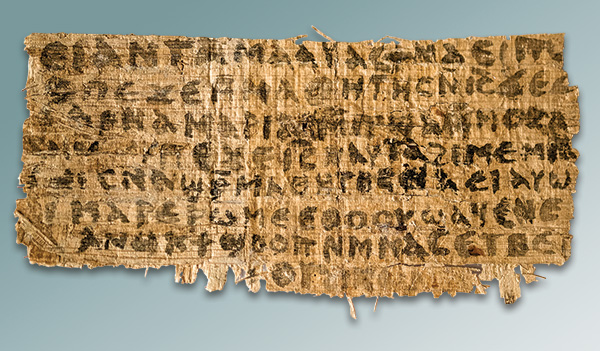

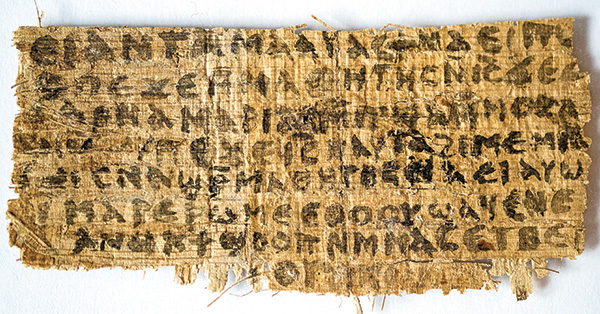

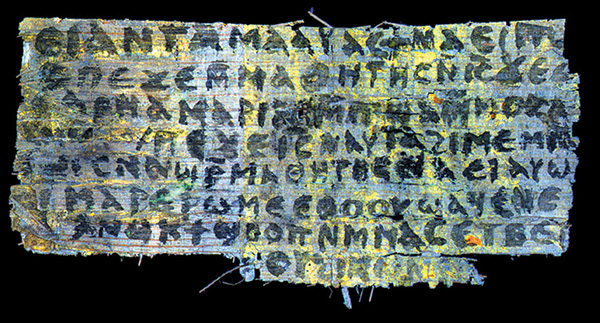

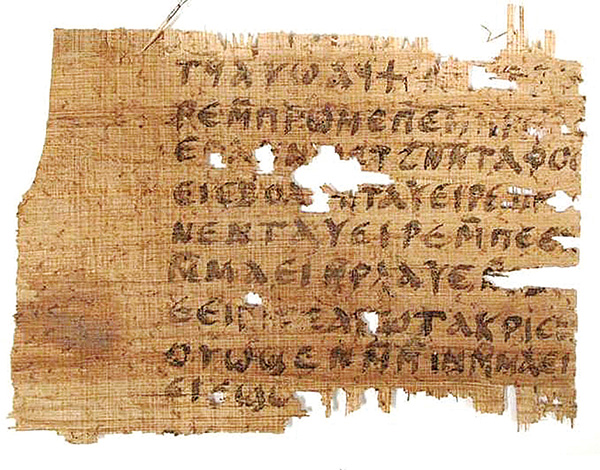

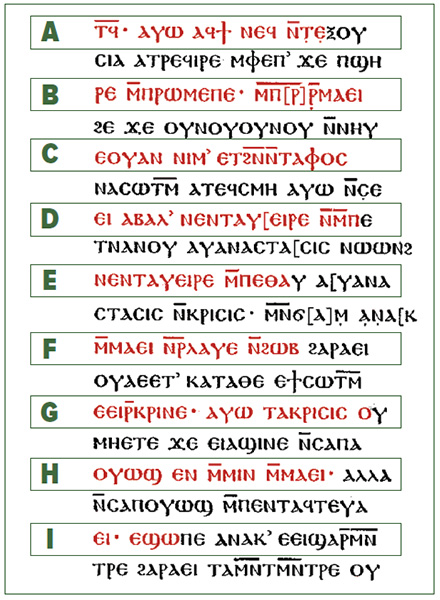

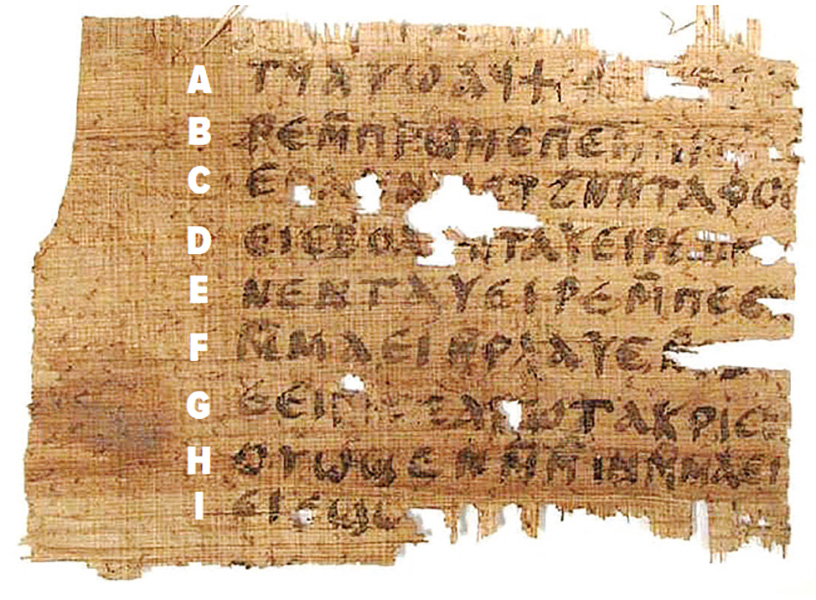

In this case, King drafted a lengthy manuscript on the little papyrus fragment the size of a business card with eight incomplete lines on one side and six illegible lines on the reverse. It is the only known text from antiquity in which Jesus states he has a wife. King presented her study in September 2012 at a scholarly conference in Rome. Before doing so, however, she consulted two other experts, one a professor at Princeton University (Anne-Marie Luijendijk) and the other the head of New York University’s Institute for the Study of the Ancient World (Roger Bagnall), both of whom supported King’s analysis and found nothing to suggest that the writing was a modern forgery. Bagnall noted that the ink was battered and faded. “It would be impossible to forge,” he said. “A fragment this damaged probably came from an ancient garbage heap,” Luijendijk observed.

King was also careful to emphasize that in her judgment this Coptic fragment (which she dubbed the “Gospel of Jesus’ Wife” or GJW) “provides no reliable historical information” as to whether or not Jesus was married, only that “some Christians depicted him as married [at the time this text was composed].” (At that time in her analysis, King dated the fragment to the fourth century C.E. and thought the text was probably composed in the second century C.E. Later carbon-14 tests indicated that this fragment was written on eighth-century C.E. papyrus).

King had received the papyrus fragment to study from a collector who wished to remain anonymous. There is no question that the fragment is unprovenanced; that is, we have no idea where it came from. King speculates that, considering its condition, it probably came from a garbage dump or perhaps from an ancient burial site. As she also tells us, this is no different from similar documents that have reached us: “The provenance of most Coptic Papyri, however, remains uncertain.”

King submitted her analysis of the manuscript for publication in the Harvard Theological Review 057 (HTR), a highly regarded, peer-reviewed scholarly journal. The manuscript was accepted and scheduled for publication in the January 2013 issue.

King had also posted her Rome talk online. At this point, both the text and a picture of the papyrus fragment became widely available both to the public and to the small community of Coptic scholars. (Coptic is a form of late Egyptian.)

Among them was a Coptic scholar at Brown University named Leo Depuydt. He had no need to examine the fragment itself to reach his conclusion. A picture of the fragment was enough. Within “two minutes after I saw it on the screen, [Depuydt reported] … it stinks! … [Even] as a forgery, it is bad to the point of being farcical.” Depuydt based his conclusion on what he regarded as grammatical errors in the Coptic; in his judgment it was “a grammatical monstrosity … [I]t could be done in an afternoon by a graduate student.” He saw “no need for outside references or scientific tests.”

Both his certainty and dismissive—even disrespectful—tone toward other scholars brought widespread incredulity to his claims. In another analysis, British scholar Francis Watson at the University of Durham also concluded that the fragment was a forgery but in less barnyard terms; however, Watson’s analysis too was criticized by University of Helsinki scholar Timo Paananen in more customary scholarly jargon; Paananen charged Watson with reaching his conclusion by “circular reasoning … [His analysis] fails to distinguish between authentic and fake passages.”

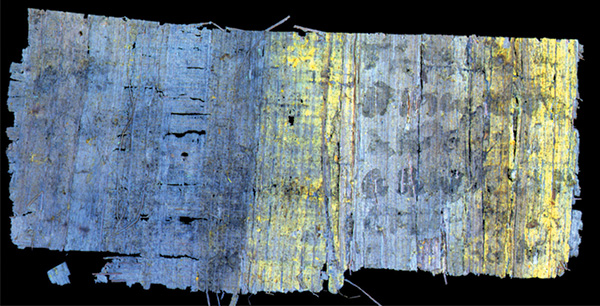

At this point, HTR decided to postpone publication of King’s paper until further tests on the papyrus had been undertaken by other experts. This process consumed much of the next two years. The tests included a chemical study of the ink through Micro-Raman Spectroscopy, a study of the writing with Fourier Transform Infrared Microspectroscopy, a study with Accelerated Mass Spectrometry Radiocarbon Determination of papyrus samples and a preliminary paleographical assessment.

As noted earlier, two radiocarbon tests dated the papyrus fragment to the eighth century, and King argued that this was a copy at that time of a fourth-century manuscript which was itself taken from a second-century composition.

058

Considering all this additional study, King concluded that the “current testing thus supports the conclusion that the papyrus and ink of the GJW are ancient.” As for the possibility of a forgery, King recognized that “a clever forger could acquire a piece of ancient papyrus and fabricate ink from ancient papyrus fragments of other vegetable matter—both of which would pass these kinds of inspection.” This would be extremely difficult to do, however. “Papyrologists agree that the clumsiness of the script indicates an unprofessional hand but differ in their evaluation of whether it is due to the elementary education level of an ancient writer or a forger’s inexperience writing on papyrus.” Weighing against a judgment of forgery in King’s mind was that the supposed forger would have to be extremely skilled in obtaining ancient papyrus and creating ink with an ancient technique (and leaving no ink traces out of place at the microscopic level) and yet be so incompetent as Depuydt claims in the Coptic language and with such poor scribal skills. “In my judgment,” she wrote, “such a combination of bumbling and sophistication seems extremely unlikely.”

At this point King also gave the fragment to another leading Coptic specialist, Ariel Shisha-Halevy of Hebrew University, who had been Depuydt’s teacher in graduate school. Shisha-Halevy concluded that “on the basis of grammar and language—the text is authentic.” Depuydt was unimpressed. “I don’t need any papyrus or ink tests. I already know it is a fake,” he said.

Following all this brouhaha, HTR decided to publish King’s updated article and did so in its April 2014 issue. However, HTR also gave Depuydt an opportunity to make his case in the same issue. He was neither less certain, nor less blunt than he had previously been: “[I have] not the slightest doubt that the document is a forgery, and not a very good one at that.”

In her response in this issue of HTR, King was no less direct: “The arguments of Depuydt are not persuasive … The grammatical ‘blunders’ Depuydt posits are the result of incorrect analysis or can be accounted for as examples of known, if relatively rare, native Coptic usage.”

Nor did Depuydt change Roger Bagnall’s mind: “I haven’t seen any argument that I find at all compelling that would indicate that it’s not genuine, that it’s not ancient.”

After this publication in HTR, it seemed that a consensus was building that the text of the fragment was authentic. As the New York Times put it, “The taint of forgery suspicions [was] seemingly allayed.”

Before HTR had initially withheld publication of King’s article, the Smithsonian Institution in Washington had made a TV program about the “Gospel of Jesus’ Wife.” When HTR pulled the article from its publication schedule, the Smithsonian 059 decided against airing its one-hour TV special. After the HTR publication in 2014, however, the Smithsonian was confident enough that the text was authentic that it aired its TV program.

Within days of the publication of all the new evidence and analysis in HTR, however, a bombshell hit the scholarly world relating to the “Gospel of Jesus’ Wife.” Unfortunately, the story is a little complicated.

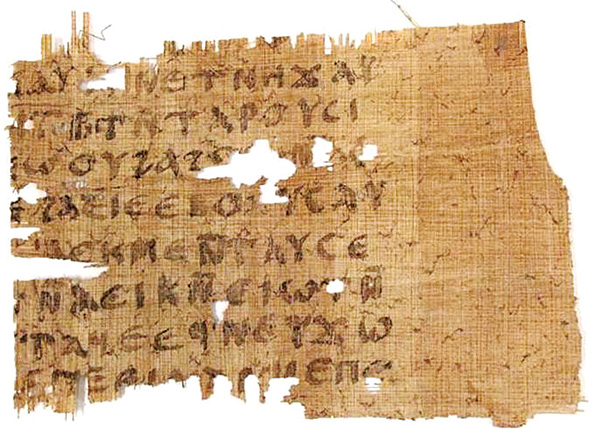

The papyrus fragment we have been talking about was not the only one that the anonymous collector had brought to King. Another was a slightly larger fragment from the Gnostic Gospel of John, which is, like the “Gospel of Jesus’ Wife,” in Coptic.

Enter Christian Askeland, a 38-year-old American Coptic scholar associated with Indiana Wesleyan University in Marion, Indiana. Askeland had written his freshly minted Ph.D. dissertation on the Gnostic Gospel of John, so his interest lay not so much in the “Gospel of Jesus’ Wife,” but in the fragment of the Gnostic Gospel of John that came to King with the “Gospel of Jesus’ Wife.” Askeland knew of another Gnostic Gospel of John in Coptic (henceforth CGJ) known as the Codex Qau. He decided to compare it to the fragment of CGJ that had come to King with the “Gospel of Jesus’ Wife.”

What Askeland found was astounding. The text of the small fragment of CGJ replicated every other (every second) line from a leaf of the Codex Qau, which was discovered in 1923 in an ancient Egyptian grave and is therefore universally recognized as authentic. Moreover, for 17 lines the breaks in the lines of the fragment of CGJ in King’s possession were identical to the breaks in the lines of CGJ in the Codex Qau. Whoever had penned the fragment of CGJ in King’s possession had obviously copied the text of CGJ from the Codex Qau. He or she simply copied the beginning of every other line from the Codex Qau. The forger even copied a typo in the online edition from which he copied. It therefore seems almost certain that the fragment of CGJ in King’s possession is a modern forgery.

So what does this have to do with the “Gospel of Jesus’ Wife”? Answer: “The Gospel of Jesus’ Wife” is written in the same hand and with the same writing instrument as the fragment of CGJ. It came to King with the “Gospel of Jesus’ Wife.” Moreover, both fragments are written in Lycopolitan, a relatively late dialect of Coptic. In short, whoever penned the “Gospel of Jesus’ Wife” also copied the fragment of CGJ. If one is a forgery, the other is a forgery.

Is the “Gospel of Jesus’ Wife” 100 percent a forgery? Not quite. But even King has acknowledged that “this argument [for forgery] is substantive. It’s worth taking seriously. And it may point in the direction of forgery.”

I contacted Karen King to see what her present position is. She did not return repeated emails.

Although he is not an archaeologist, Canadian/Israeli TV journalist and producer Simcha Jacobovici (pronounced Yacobovitch) has made some remarkable archaeological discoveries.

You have already read your free article for this month. Please join the BAS Library or become an All Access member of BAS to gain full access to this article and so much more.

Already a library member? Log in here.

Institution user? Log in with your IP address or Username