The Search Begins: The Fathers of Historical Jesus Scholarship

17

During the Enlightenment, the historian’s job changed dramatically. It was no longer enough simply to chronicle events reported in earlier, authoritative texts. Tradition and authority had become suspect, as investigation and reason became the new basis for knowledge. For the first time in history, historians were beginning to ask, What really happened?

In religion and theology, the early bearers of the Enlightenment were called the Deists. Like their counterparts in the fields of history and science, they sought “reasonable” and “natural” explanations for supernatural events. Although they believed in God, they rejected the notion of divine intervention and special revelation. They saw scripture and doctrine as human products.

Until this time, it was generally accepted that anyone could know what Jesus was like simply by combining everything that was said about him in the Bible. Now, scholars began distinguishing the Jesus of the Gospels from the historical Jesus. The first to do so was Hermann Samuel Reimarus:

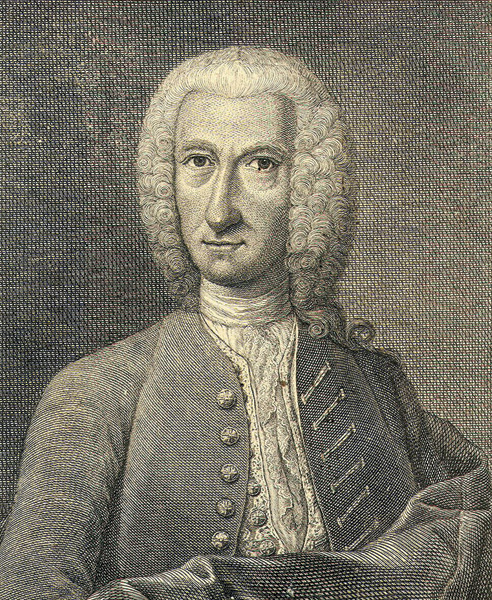

Hermann Samuel Reimarus

(1694–1768)

It is, perhaps, not surprising that the work that marks the birth of historical Jesus scholarship was published anonymously and posthumously. The author’s family feared the text would bring shame on their name; the local Duke of Brunswick, Germany, prohibited publishing works detrimental to religion. And so Hermann Samuel Reimarus’s On the Intention of Jesus was released in 1778 as “fragments” of a manuscript by an unknown author discovered among the treasures in the duke’s library.

Born in Hamburg, Germany, into a family of Lutheran clergy, Reimarus lived in the time of the Enlightenment, that period of Western intellectual history that has decisively shaped the modern mind and modern culture. In his twenties, he studied in England and Holland, where he was exposed to a number of “Deist” thinkers, who generally denied both supernatural intervention or revelation. After returning to Germany, Reimarus became a professor of Oriental languages in a gymnasium (advanced high school) in Hamburg, where he taught for the last forty years of his life. Although publicly he remained a practicing Lutheran, privately he entertained very different ideas.

In On the Intention (or Aim or Purpose) of Jesus, Reimarus contended that the intention of Jesus during his lifetime differed radically from the intention of his disciples (and the gospel writers) after his death. Jesus’ own aim, according to Reimarus, centered on the establishment of the Kingdom of God. Noting that Jesus himself never explained what the kingdom was, Reimarus suggested that for Jesus, it must have meant exactly what it meant in the popular language of Jesus’ day: namely, a political kingdom that would involve the overthrow of Roman rule and the establishment of an earthly messianic kingdom centered in Jerusalem. Jesus went to Jerusalem at Passover expecting to incite a popular anti-Roman uprising. However, he seriously overestimated his popularity and instead was arrested, abandoned and executed.

His unexpected death left the disciples in a situation not to their liking. Faced with the unpalatable prospect of returning to their difficult and dull former lives, they decided to try to keep the movement alive. This they did with two major inventions.

First, they created the resur-rection account. (According to Reimarus, they probably stole Jesus’ body from the tomb in order to make the story more convincing.) Second, they invented the notion of Jesus’ second coming and transformed Jesus’ this-world kingdom of God into an end-time Kingdom of God. In order to convince people to join their movement immediately, they suggested that this second coming was imminent.

Thus, Jesus’ intention was to establish a Jewish political kingdom; the disciples’ intention post-Easter was to establish a new religion that they would lead. For Reimarus, Christianity was the invention of their conniving minds.

Seen through the lens of modern scholarship, Reimarus’s arguments are both crude and unpersuasive. He used sources uncritically, imposed a consipriacy theory on the texts and was motivated more by polemics than scholarship. Yet, in a number of respects, his work anticipated much modern scholarship.

Reimarus’s claim that the Kingdom of God was central to Jesus’ message has been accepted by most scholars. His preference for the Synoptic Gospels (Matthew, Mark and Luke) as more historical has become foundational. Further, his central claim—that the message of Jesus was different from that of the gospel writers—is bedrock among modern scholars.

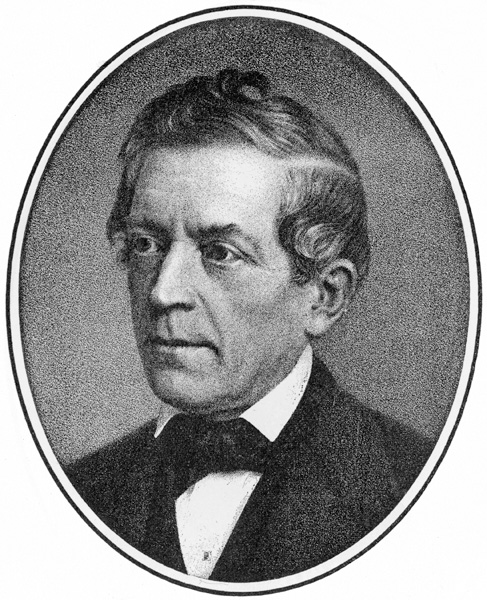

David Friedrich Strauss

(1808–1874)

David Friedrich Strauss was a young man when he published The Life of Jesus Critically Examined—two volumes of over 1,400 densely written pages. Born in 1808 in a 18village near Stuttgart, he studied theology at Tübingen and by age 22 was a vicar in a country church in southwestern Germany. Shortly thereafter, he went to the University of Berlin to study with Hegel, who died almost immediately after Strauss’s arrival. In 1832, at age 24, Strauss was back at Tübingen as a tutor and lecturer, and at age 27 his magisterial work was published.

It was wildly controversial. One reviewer called it “the Iscariotism of our days” and another “the most pestilential book ever vomited out of the jaws of hell.” The book went through several editions, and within ten years had been translated into English by Marian Evans, better known in English literature as George Eliot.

It cost Strauss his university career. Dismissed from his position at Tübingen, he then secured an appointment at Zurich, only to be pensioned off before he gave his first lecture. He never again had a teaching appointment. During the rest of his life, he wrote a number of other books (including another Life of Jesus in 1864, aimed at a popular audience), entered into an unhappy marriage with an opera star in 1842, dabbled in politics, and died in 1874. At his own request, he was buried without Christian ceremony.

What made his book so controversial was his treatment of much of the Gospels (especially the miraculous elements) as “mythical” in character. To appreciate his contribution, we must set his argument in the context of the theological and biblical controversies of his day.

In the decades prior to Strauss, theologians, scholars, and church people were struggling with the impact of the Enlightenment upon the Bible. Much of the struggle concerned how to understand stories of the miraculous.

Two major positions—“rationalist” and “supernaturalist”—warred with each other. Rationalist scholars (many of whom were Deists) claimed that violations of the laws of nature were impossible, that “miracles” could not happen, and hence sought a natural explanation of the miracle texts.

Interestingly, the rationalists accepted a historical basis for the miracle stories in the Gospels, but denied that miraculous causation was involved. For example, they affirmed that the disciples really thought they saw Jesus walking on the water, but in fact he was walking on a row of submerged rocks just below the surface of the water.

“Supernaturalists,” on the other hand, defended not only the historical accuracy of the biblical accounts, but also the element of direct divine causation. For them, the miracles were exactly what they appeared to be: divine interventions into the natural order.

Strauss disagreed with both, and argued for a third approach. His method can best be illustrated by looking at his treatment of a particular miracle story, Jesus’ feeding of 5,000 people with a few loaves and fishes. The story is found in both the Synoptics (Mark 6:30–44//Matthew 14:13–21//Luke 9:10–17), and in somewhat different form in John 6.

Strauss attacked the rationalist approach. Noting that, according to John’s version, a young boy contributes the five loaves and two fishes, the rationalists argued that the boy’s example motivated others in the crowd to share the provisions they had brought with them, and so 5,000 people were unexpectedly fed “in a desert place.” For the rationalists, the “happenedness” of the story remains, but the miracle disappears. It becomes instead a story about the importance of sharing. Strauss argues that this approach destroys the plain meaning of the text: The gospel purports to report a miracle.

Strauss also attacked the supernaturalist reading, which asserted that Jesus really multiplied five loaves and two fishes into an amount sufficient to feed 5,000 people. Strauss questions this interpretation by inviting us readers to try to imagine what we might have seen if they had been there.

One possibility is that Jesus could have multiplied the loaves and fishes all at once, so that if we had been there, we would have seen an enormous pile of bread and fish appearing all at once. Or the multiplication could have occurred as Jesus handed the loaves and fishes to the disciples, or as the disciples distributed the food to the crowd—and so we would have seen loaves and fishes miraculously being replaced in his hands or in their hands. Strauss finds all of these options impossible to imagine. As soon as the story is exposed to the sober light of history, he suggests, it disappears as a historical story.

Having rejected both the rationalist and supernaturalist approaches, Strauss then argues for a mythical approach. Rather than reporting something that really happened (with either a rational or supernatural explanation), the text has a different purpose. Namely, the text uses the imagery of the early church’s inherited religious and literary tradition (the Hebrew Bible as a whole, and in this particular case, the story in Exodus 16:13–36 of God feeding the people of Israel in the wilderness with manna) to make a statement about the spiritual significance of Jesus. That is, the point of the text is not to report what Jesus did on a particular day, but to make the claim that Jesus is “the bread of life” who feeds his followers with “spiritual food” even to this day.

Strauss follows this same procedure with text after text. The virgin birth, Jesus’ vision at his baptism, the story of his transfiguration, the healing miracles—all are understood as the product of the early church’s use of Jewish ideas about what the Messiah would be like in order to express the conviction that Jesus was indeed the Messiah.

The details of Strauss’s argument have not had a lasting impact. Yet his basic claims—that many of the gospel narratives are mythical in character, and that “myth” is not simply to be equated with “falsehood”—have become part of mainstream scholarship. What was wildly controversial in Strauss’s time has now become one of the standard tools of biblical scholars.

19

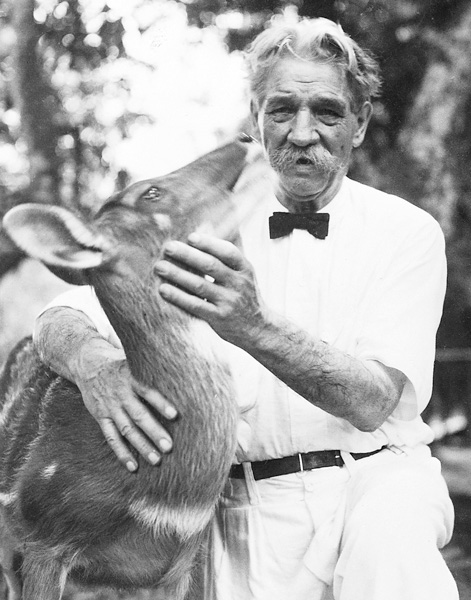

Albert Schweitzer

(1875–1965)

Albert Schweitzer was one of the few great geniuses of the 20th century. Known for his philosophy of “reverence for life” and famous as a medical missionary to Africa, a modern saint and a recipient of a Nobel Prize, he also had a towering influence on New Testament scholarship.

A precocious genius, by the age of 30 Schweitzer had written two books on the historical Jesus that decisively shaped 20th-century scholarship. The Mystery of the Kingdom of God (1901) was the prelude to his classic The Quest of the Historical Jesus (1906). In the latter volume, he masterfully surveyed the history of Jesus scholarship up to his day, sketched a portrait of Jesus with such persuasive power that its broad strokes have dominated much of this century’s scholarship and virtually brought the quest for the historical Jesus to an end for half a century.

Schweitzer’s central claim was that Jesus expected the end of the world in his own time. He argued that both the Kingdom of God and the Son of Man are eschatological concepts. Jesus expected “the last things”—the end of the world, the resurrection of the dead, the final judgment and the coming of the Kingdom of God—and he expected them soon.

Schweitzer was even more specific: Jesus was not simply an end-of-the-world prophet who proclaimed that the end would be sometime soon, perhaps within a few decades. Rather, Jesus saw himself as an instrument for bringing about the end. He believed that, before the end could come and God would intervene, a sequence of events would occur: the return of Elijah, a period of radical repentance, and the suffering and persecution of the righteous (the “messianic woes” of the end time).

Jesus set out to fulfill this scenario by creating the conditions that would lead God to establish the Kingdom of God. He declared John the Baptist to be Elijah. He issued the call to repentance: “Repent, for the Kingdom of God is at hand!”

All that remained was the suffering of the righteous, the “messianic woes.” Initially Jesus thought this suffering and the subsequent end would come during his lifetime. When it did not, Jesus concluded that he himself must suffer and die in order for the Kingdom to come. He realized that he must bear the suffering of the end time “on behalf of the many.”

Thus Jesus went to Jerusalem, deliberately planning to get himself killed. He entered the city in a provocative fashion, dramatically disrupted the Temple and stridently indicted the ruling and religious elite. His provocations succeeded: The authorities arrested him and condemned him to death. On the cross, Jesus expected that God would now intervene, transform him into the eschatological Son of Man and bring in the Kingdom of God.

He was, of course, mistaken. In the words with which he concludes his account of Jesus’ death, Schweitzer hints that at the end, Jesus may have realized this: “At midday of the same day—it was the 14th Nisan, and in the evening the Paschal lamb would be eaten—Jesus cried aloud and expired. He had chosen to remain fully conscious to the last.” And what was Jesus’ final cry? “My God, my God, why hast thou forsaken me?”

Stated so compactly, Schweitzer’s understanding of Jesus may seem both bizarre and outrageous. Yet it is impressive, partly because it explains so much of the gospel tradition: the sayings about the nearness of the kingdom and the coming of the Son of Man, the urgency of Jesus’ call to repent and his radical ethic, even Jesus’ death as “vicarious,” intended by him as a death “on behalf of the many.”

One might think that Schweitzer’s portrait of Jesus as a mistaken apocalypticist, if taken seriously, should mean the end of Christian belief. But that was not even true for Schweitzer himself. Instead, Schweitzer argued for a radical separation between historical research and theology: What Jesus was like as a figure of history is irrelevant to the truth of Christianity which, for Schweitzer, is grounded in the present experience of Christ as a living spiritual reality. Schweitzer concludes his famous book with one of the most widely read paragraphs in 20th-century theology:

“He comes to us as One unknown, without a name, as of old, by the lakeside, He came to those who knew him not. He speaks to us the same word: ‘Follow thou me!’ and sets us to the tasks which he has to fulfill for our time. He commands. And to those who obey Him, whether they be wise or simple, He will reveal Himself in the toils, the conflicts, the sufferings which they shall pass through in His fellowship, and, as an ineffable mystery, they shall learn in their own experience Who He is.”

Schweitzer’s influence on subsequent Jesus scholarship was immense. Though few scholars accepted the more specific details of his reconstruction, his general claim that Jesus’ message is to be understood within an end-of-the-world framework became a near-consensus in mainstream scholarship, which only recently has shown signs of weakening.

Moreover, Schweitzer’s claim that historical Jesus scholarship has no theological significance contributed to a relative lack of scholarly interest in the historical Jesus for a major portion of this century. His work was thus not only the high water mark of the “old quest” for the historical Jesus, but brought the quest to a close for half a century.

This article is based on the following three essays by Marcus Borg, which appeared in The Fourth R, the journal of the Westar Institute, which is published by the Polebridge Press in Sonoma, California: “Reimarus and the Beginning of the Quest,” November 1991; “David Friedrich Strauss: Miracle and Myth,” May 1991; and “Albert Schweitzer’s View on Jesus and the End of the World,” May 1990.

During the Enlightenment, the historian’s job changed dramatically. It was no longer enough simply to chronicle events reported in earlier, authoritative texts. Tradition and authority had become suspect, as investigation and reason became the new basis for knowledge. For the first time in history, historians were beginning to ask, What really happened? In religion and theology, the early bearers of the Enlightenment were called the Deists. Like their counterparts in the fields of history and science, they sought “reasonable” and “natural” explanations for supernatural events. Although they believed in God, they rejected the notion of divine intervention and special […]

You have already read your free article for this month. Please join the BAS Library or become an All Access member of BAS to gain full access to this article and so much more.

Already a library member? Log in here.

Institution user? Log in with your IP address or Username