The Sepphoris Synagogue Mosaic

Abraham, the Temple and the sun god—they’re all in there

048

Sepphoris—“the ornament of all Galilee”1—is a city of mosaics. It seems that wherever excavators dig they turn up mosaics. More than 40 mosaic floors, many of them extremely elaborate, have been uncovered to date. BAR readers are already familiar with the mosaic scene that features the lovely woman known as the “Mona Lisa of the Galilee”2 and with the scenes that decorate the Nile festival building.3 To these masterpieces we can now add another stunning example of mosaic art: a 44-by-15-foot carpet that covered the floor of a fifth- to seventh-century C.E. synagogue.

The Sepphoris synagogue mosaic is remarkable in several respects: It is large and in many places relatively well preserved. Even where it is not well preserved, we can puzzle out most of its content. Most of it is distinctly Jewish, with Biblical characters and Jewish religious objects. But some of it seems oddly pagan: It contains a large zodiac with—surprisingly—the sun god at its center. As we shall see, the mosaic as a whole bears a powerful message, one that would have reverberated strongly with the hopes of its congregants.

We discovered the synagogue in 1993 while preparing to open Sepphoris to the public as a national park.4 A bulldozer operating in the northern part of the city scraped the earth, revealing a row of white tesserae (the small cubes of stone or glass that mosaics are made of). Even then, 050we had no idea that such a large, intricate mosaic lay below. A few days later we uncovered a dedicatory inscription written in Aramaic; it read “May they be remember[ed] for good, Tanhum son of Yodan and Semqah and Nehorai the sons of Tanyhum, Amen.” We knew we were on the brink of something important.

Soon we had uncovered the large rectangular structure that housed the mosaic. Very little of the walls remained (they had been robbed out over the centuries), but what was still extant showed that the building had been built of finely worked stone blocks. Coins embedded under the mosaic floor dated to the early fifth century C.E. (Soundings conducted underneath the mosaic bedding after the 051mosaic was removed yielded some earlier structures, mostly from the Roman period.) The synagogue existed only during a single phase before it was apparently abandoned in the seventh century C.E., perhaps after the Persian conquest in 614 C.E. or the Arab conquest of 638 C.E.

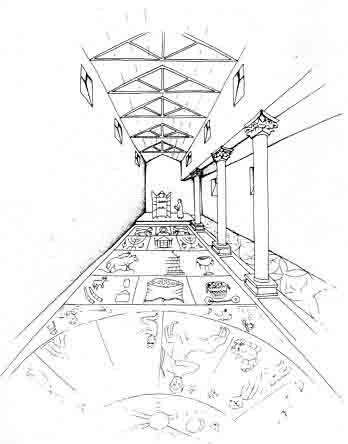

The synagogue is long and narrow, measuring 68 feet by 28 feet, and runs roughly east to west, an alignment dictated by the city’s street grid. The bimah (the elevated platform that supports the Holy Ark containing the Torah scrolls) was at the west end of the building. As a result of this orientation, the worshipers did not face Jerusalem, which is south of Sepphoris, when they prayed. Although it is often stated that ancient synagogues (like modern ones) were oriented toward Jerusalem, this is not invariably true, especially among ancient synagogues near Sepphoris. The synagogues of Japhia, Ussfiyeh and Horvat Sumaqa, like Sepphoris, were also not oriented toward Jerusalem.5

A row of columns separated the main hall (nave) from a side aisle. The building is unusual in that it has an aisle on only one side. The columns that separated the main hall from the side aisle were robbed in antiquity; they originally stood on simple bases, one of which we recovered in situ.

Another striking feature of the Sepphoris synagogue is the absence of an apse at one end, which traditionally housed the Torah ark in Byzantine-era synagogues.

Nor did we find any evidence of a women’s gallery. By now it is widely accepted among scholars that synagogues from the early centuries of the Common Era did not have a separate women’s section.6 This may surprise people whose knowledge of Jewish synagogues derives from contemporary Orthodox or pre-Second World War European examples.

Worshipers entered the Sepphoris synagogue through a doorway on the south side of the building, near the eastern end. The threshold of this entrance remains in situ. The doorway led to a long, narrow entrance hall (narthex). Once inside, worshipers would turn left to enter the synagogue’s main hall. There they would be confronted with the mosaic.

Unlike many other ancient synagogues, ours did not have stone benches built along the walls. Worshipers sat on either wooden benches or on mats, neither of which would have survived. The main hall probably had a gabled roof and clerestory windows for light to enter.

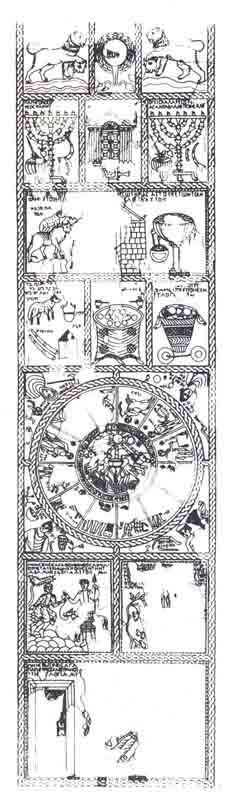

The mosaic consists of seven wide bands, some of which are subdivided into 052smaller panels. The central focus is the circular zodiac set inside a square near the center of the floor.

The entire mosaic is bordered by a blue, red and yellow guilloche decoration (a double-strand rope pattern). This same pattern runs between the seven bands and between the subdivided panels. Let us follow in the footsteps of the ancient worshipers as they entered the main hall and approached the elevated bimah at the far end.

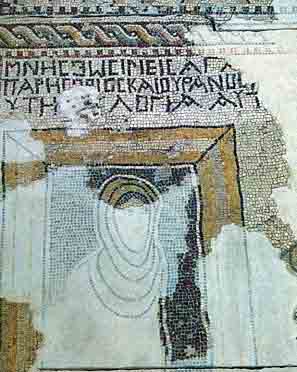

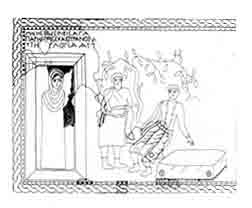

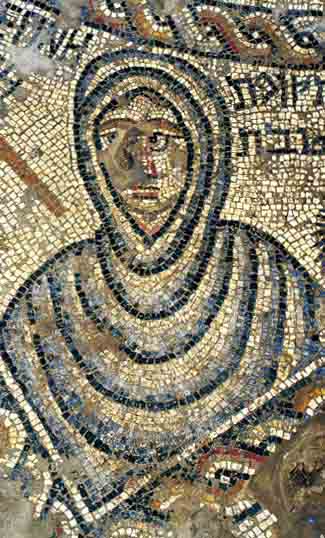

Unfortunately, the first panel inside the entrance is badly damaged, more so than any of the other panels. But, enough of it is intact to give us a fairly good idea of what it once depicted. At far left, framed by a doorway, we can see the cloaked head of a woman (see photo and drawing); slightly to the right is the edge of a garment belonging to another figure; just below center we can see the lower part of a third figure, shown reclining. A small section of a fringed hem lies along the bottom border. The writing above the woman’s head, like many of the inscriptions in the mosaic, is a dedicatory inscription, only partially preserved, honoring donors to the synagogue and has nothing to do with the scene in which it is found.

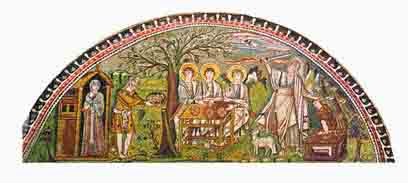

This band probably shows the visit Abraham and Sarah received from three angels, who promised the elderly couple an heir (Genesis 18:1–15). The mid-sixth-century C.E. wall mosaic from the Church of San Vitale, in Ravenna, Italy, is a close parallel to this scene. There, too, 053Sarah wears a hooded robe and stands inside a doorway at left. Next to her, Abraham offers a plate of food to his visitors, who sit behind a table at center. At right in the Ravenna mosaic is the binding of Isaac, a scene we encounter in the Sepphoris mosaic as well. If we are right about our interpretation, then the Sepphoris mosaic contains the earliest depiction known in Jewish art of the visit of the angels to Abraham and Sarah.

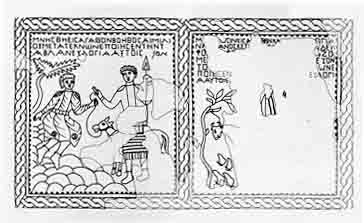

The next band depicts the binding and near sacrifice of Isaac (Genesis 22). This band is divided in two; the left panel shows Abraham’s two servants and, in the foreground, the ass, all of whom accompanied the father and son as they climbed Mt. Moriah in obedience to God’s command. The semicircles at lower left may indicate the foothills of Mt. Moriah. The inscription above the scene reads, “Be remembered for good Boethos (son) of Aemilius with his children. He made this panel. A blessing upon them. Amen.”

The right-hand panel continues the story, but most of it has not survived. To the far left we see an animal tethered to a tree by a rope, which is tied to one of its horns. This is the ram who will be substituted for Isaac as the sacrifice. In the middle of the panel a small but significant detail of the mosaic still survives: a section of a pointy blade held upright and, to the right of it, a portion of a robe. Abraham, about to sacrifice his son, and Isaac once occupied the center of this panel. Below the ram are two upturned pairs of shoes. The upturned shoes, no doubt belonging to Abraham and Isaac, indicate that they are 054standing on holy ground. (Remember that when Moses approached the burning bush, God instructed him to remove his shoes because he was standing on “holy ground” [Exodus 3:5].)

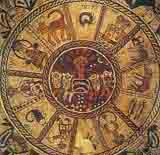

The next panel contains the mosaic’s pièce de résistance, the circular zodiac with the sun god at its center. It sits almost in the middle of the floor and measures 11 by 11 feet.

The outer rim of the zodiac wheel is framed by a guilloche pattern, as are the borders of each band of the mosaic. Four of the 12 zodiac signs are almost intact; the other 8 are damaged to a greater or lesser extent, but they all preserve some detail that allows us to identify them. In addition, the signs are identified by Hebrew inscriptions, half of which have survived. Each sign is also identified by the Hebrew month to which it corresponds. A star appears in the upper right or the upper left of each sign.

The signs run counterclockwise. We will begin with summer, at lower right in the photo on pp. 56–57, with Cancer, the crab, shown from above (between 5 and 6 o’clock); next to the crab, a youth in a short tunic and black shoes is shown frontally.

We can only see the hind legs of Leo, the lion (between 4 and 5 o’clock), but 055we can assume that it was depicted while leaping; the legs of a youth are also visible. Nothing remains of Virgo, the virgin (between 3 and 4 o’clock), except two ears of wheat, which she probably carried, in the upper right of her panel.

Libra, the first of the signs in fall, is much better preserved (between 2 and 3 o’clock); a young man holds scales in his right hand. Scorpio (between 1 and 2 o’clock), like the crab, is seen from above, while a youth resembling the figure in the previous panel stands at left.

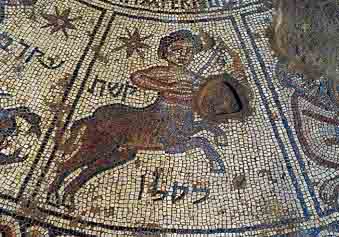

A leaping centaur, grasping a bow and arrow in his forelegs, represents Sagittarius, the archer (between 12 and 1 o’clock).

Little remains of Capricorn, the goat (between 11 and 12 o’clock), the first sign in winter. Apparently a kneeling youth held the goat’s hindquarters. Aquarius, the water carrier (between 10 and 11 o’clock), is even more damaged, with only flowing water visible at the bottom of the panel. Pisces, the fish (between 9 and 10 o’clock), however, is almost completely preserved and shows a youth holding two fish dangling from a hook.

For the spring signs, we have Aries, the lamb (between 8 and 9 o’clock), and Taurus, the bull (between 7 and 8 o’clock), shown galloping; each is accompanied by a youth. Gemini, the twins (between 6 and 7 o’clock), are naked and embracing; the twin on the right seems to be holding a stringed instrument, the one on the left a club.

In each corner of the square containing the zodiac wheel is the bust of a woman, the personification of one of the four seasons—a standard feature of zodiac depictions. The four figures are labeled in Greek and Hebrew and appear next to the months they represent. Fruits and agricultural implements appropriate to the season accompany each woman. In the lower left corner, Spring (identified here as Nisan, after the Hebrew month that corresponds roughly to April), wearing a sleeveless dress, is flanked on the right by a sickle, a basket of flowers and two lilies, and on the left, by a bowl of flowers and roses.

Summer (Tammuz, or roughly July), at lower right, is partially destroyed, but seems to be naked. To the right is a sheaf of wheat, while on the left is a serrated blade and a second tool, presumably agricultural.

Fall (Tishri, late September/early October), at upper right, is flanked by two pomegranates and other fruits on the right, and by a vine branch with tendrils on the left. The latter probably bore a bunch of grapes.

Winter (Tevet, January; at upper left) 058is a mournful figure. Her head is wrapped in a grayish cloak; a tree with a drooping branch, a small sickle and an unidentified fruit are at right, and an ax with a long handle is at left.

As surprising as it may seem to find a zodiac in a synagogue, it is even more shocking to find a depiction of the sun god, Helios, riding in his chariot drawn by four horses (the quadriga). But the fact is that both the zodiac and Helios with his quadriga have been found in several ancient synagogues—at Hammat-Tiberias, Beit Alpha, Na’aran and Ussfiyeh, among others. But unlike these other examples, which do not shy away from picturing Helios anthropomorphically as a young man riding a chariot, the Sepphoris mosaic represents him only with a sun disk and a chariot.

A narrow inscribed circular band (it mentions the donors of this panel) separates the central scene from the zodiac depictions. Various parts of the chariot are portrayed in different perspectives—much like a modern Cubist painting. In the center the chariot is shown head-on, but the two wheels are portrayed in profile. The four horses pulling the chariot are also shown in profile, with the inner pair looking in and the outer pair looking out. In the upper right are a moon and a star against a blue background. The moon is shown as a full circle; its crescent consists of white tesserae, as if lit, while the rest of it is dark brown. The sun dominates the center of the sky, with ten rays radiating in all directions. The bottom ray descends to the chariot, creating the impression that the sun itself is riding in the vehicle.

How should we understand the presence of a zodiac and of Helios with his quadriga in a synagogue? We believe they must be understood in context with the other very Jewish features of the mosaic, so we will postpone consideration of the question until we have described the full picture before us.

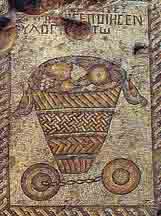

The images on the next three bands of the mosaic are all related to the objects and rituals of the wilderness Tabernacle and the Jerusalem Temple. The band directly above the zodiac is divided into three panels. The right panel shows a plaited wicker basket full of fruit—the firstfruits that Deuteronomy 26:2 tells us must be brought to the Temple in a basket. Atop the basket we can see a bunch of grapes, a pomegranate and a fig. Two birds hang from the side of the basket. This detail seems to be based on rabbinic tradition. The Talmud says, “Rabbi Yose taught: They did not put pigeons on top of the basket, so as to avoid dirtying the first fruits, but suspended them outside the basket.”7

The center panel of this band depicts the shewbread table in the desert Tabernacle (see Exodus 37:10–11). A dozen round loaves, some of them now missing, are arranged in three rows—three loaves, six loaves and three loaves—atop the table. Their arrangement goes against 059Leviticus 24:6: “Place them upon the pure table before the Lord, in two rows, six to a row.” Perhaps the arrangement in the mosaic is simply a concession to the size and shape of the oval table. Above the table are two censers with triangular bases; the black specks inside represent frankincense.

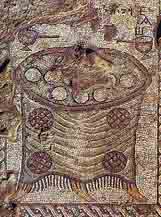

The left panel of the band is actually a continuation of the band above, so we will describe the scenes shown there before returning to this panel. At right in that higher band is a water basin set on a column with an Ionic capital. The basin is full, with the water represented by wavy bluish lines. On each side of the basin, water flows out of the mouths of two animal heads, perhaps bulls’ heads, into a small bowl below. (Only the left bowl and animal heads are preserved.) In the center of the band is a large altar built of finely dressed stones resting on a stepped base. Though the left half of the altar is badly damaged, we can still see horns on the two right corners. The top of the altar is reddish, representing the eternal fire that was always kept burning on the altar.

Aaron the high priest was originally shown to the left of the altar, but only his name (between the animal heads at left) and fragments of his garment have survived. Aaron’s clothes are shown here as blue with yellow dots; a single bell has survived along the bottom hem of his garment. The mosaic thus follows the description in the Bible: “And you shall make the robe of the ephod of pure blue … And on its hem make pomegranates of blue, purple, and crimson yarns, all around the hem, with bells of gold between them all around: a golden bell and a pomegranate, all around the hem of the robe” (Exodus 28:31–35).

At far left in the panel are a bull and a lamb—animals to be sacrificed. Above the latter are the Hebrew words “one lamb,” an allusion to the one lamb to be sacrificed each morning, as prescribed by Numbers 28:4.

Now we move back to the left panel of the band below. Here we see four other objects associated with the daily sacrifice. At the upper left is the second lamb, to be sacrificed 060in the afternoon, also prescribed in Numbers 28:4. To the right of the lamb is a two-handled black jar decorated with a white line; it is identified by the Hebrew word for oil, shemen, which was offered with some sacrifices in the Tabernacle and in the Temple. The form of the vessel is Byzantine. Many jars such as this, which are used for storing liquids, have been found at Sepphoris.8 At bottom left are two slightly curved trumpets—identified by their Hebrew name, hatzotzrot—representing the trumpets that were blown when the daily offering was sacrificed. At bottom right is a square container filled to overflowing with a heap represented by black and yellow tesserae; the word for flour, solet, appears above the heap. This no doubt represents the meal offering.

We believe these panels are intended to be a pictorial representation of Exodus 29, 061which describes the consecration of Aaron and his sons to the service of the Tabernacle and the daily sacrificial offering. Exodus 29:4–9 instructs Aaron and his sons to be led to the Tent of Meeting to be purified by water; this is alluded to on the mosaic by the large water basin. Next, Exodus 29:10–11 orders Aaron to sacrifice a bull and offer it on the altar. Then God commands the daily sacrifice of two yearling lambs. “You shall offer one lamb in the morning, and you shall offer the other lamb at twilight … a regular burnt offering throughout the generations … and I will abide among the Israelites, and I will be their God” (Exodus 29:38–45); this sacrifice is depicted by the lambs in each band of the mosaic.

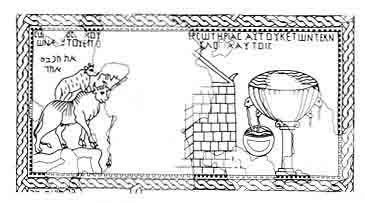

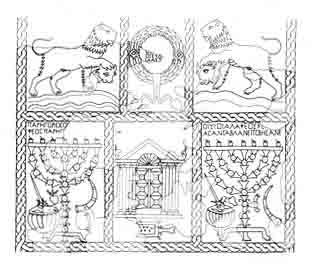

The second band from the top also contains ritual objects associated with the Tabernacle and the Temple, as well as with Jewish holidays. The left and right panels of this band are almost identical, though the one on the right is better preserved. Each is dominated by a menorah (a seven-branched candelabrum). The branches of each menorah are depicted by alternating spheres and triangles. Lions paws represent the standard four-footed base (the fourth foot is hidden behind the middle foot). A horizontal bar across the top of the menorah holds seven oil-filled cups, from which protrude wicks or perhaps thin flames. To the left of each menorah sits a bowl containing the four species associated with the festival of Sukkot, or Tabernacles: the palm branch (lulav), myrtle (hadas), willow (arava) and citron (etrog). The citron seems to be suspended above each bowl. To the right of each menorah is a shofar (ram’s horn) and tongs (only the bottom edge of the tongs has survived in the left-hand panel). Previously unknown in ancient Jewish art, tongs appear only in 13th- and 14th-century Spanish Jewish manuscripts9 and in a mosaic from the Samaritan synagogue at el-Khirbe, outside the city of Samaria.10 Now we know of their appearance in a Jewish synagogue from the fifth century C.E.

The central panel in this band shows an elaborate architectural façade, common in synagogue mosaics. In the middle are two doors consisting of three decorated squares each, a style common on wooden doors of the time. Above the doorway is a conch shell motif; to the sides are three columns with Ionic capitals that support a Syrian-style gable. Steps seem to have led up to the doors, but they have not survived. Does this structure represent an actual synagogue ark, or does it represent the Temple, which Jews hoped would someday be rebuilt? Scholars have taken both views. Perhaps both are correct.

At bottom in the panel is a single incense shovel. The hollow of the shovel is red, with some stones in dark red to represent glowing embers.

The topmost band, nearest the bimah, is the simplest section of the entire mosaic, with the fewest elements in it. Its upper half is missing, probably the result of stone robbing from the bimah. In the narrow central panel, we see a portion of a wreath that encircled a Greek dedicatory inscription; only the words “may he be blessed” have survived. We find this motif often in synagogue art, both in reliefs (such as in a lintel from Nabratein) and in mosaics (as at Hammat-Gader and Tiberias). The part of the inscription that has not survived doubtless named the donor whose beneficence enabled the work to be accomplished.

Each of the side panels shows a lion grasping a bull’s head in its forepaw. The motif of lions flanking a central scene is very common in antique Jewish art.

We do not believe that the various elements in our mosaic were simply random depictions. Instead, they make up a well-thought-out artistic program with three major themes: promise, God’s centrality in creation and redemption.

070

The promise theme is conveyed in the two bands closest to the entrance, which feature Abraham and his family. The binding of Isaac is considered by Jewish tradition the basis for God’s everlasting relationship with the Jewish people: “Because you have done this, and have not withheld your son, your favored one,” God tells Abraham in Genesis 22:16–18, “I will bestow my blessing upon you and make your descendants as numerous as the stars of heaven and the sand on the seashore.”

The zodiac scene represents the second theme. By depicting the seasons and the months and the celestial bodies, the zodiac reminds the viewer of the cyclical pattern of nature, particularly of the cycles responsible for growth and harvest. At the center of the band is the sun, which the ancients saw as the central body in the universe. The allusion to the (missing!) sun god is meant, in our view, not to make the viewer think of God in human terms—a powerful figure driving his chariot—but to serve as a reminder of God’s omnipotence: God is the force that drives the universe and its cycles. Does this still leave a puzzle as to why Jews would display in their synagogue a Greek zodiac adapted to Hebrew months and why they would choose to use a metaphor for God’s omnipotence involving a Greek god? We leave this for our readers to decide.

The third main theme in the mosaic comes from the three bands above the zodiac, which refer to the sacrificial cult of the Tabernacle and the Temple. This conveys a powerful eschatological message. Not only does Israel have a glorious past, it will have an equally glorious future. Just as God once rewarded Israel with material prosperity in return for her maintenance of the Temple cult, so would God someday redeem his people, rebuild his Temple and restore Israel to a time of plenty. This promise of redemption, the mosaic tells us, is rooted in an earlier promise, God’s vow to Abraham never to forsake his descendants.

Our mosaic is not the only example of ancient synagogue art that uses these symbols. A mosaic at Beit Alpha, with three bands showing Temple objects, a round zodiac and the binding of Isaac, comes closest to matching the Sepphoris mosaic. But no other work of ancient Jewish art conveys the themes of promise, God’s centrality in creation and hope of redemption as powerfully, in as much detail and as beautifully as the synagogue mosaic from Sepphoris.

Sepphoris—“the ornament of all Galilee”1—is a city of mosaics. It seems that wherever excavators dig they turn up mosaics. More than 40 mosaic floors, many of them extremely elaborate, have been uncovered to date. BAR readers are already familiar with the mosaic scene that features the lovely woman known as the “Mona Lisa of the Galilee”2 and with the scenes that decorate the Nile festival building.3 To these masterpieces we can now add another stunning example of mosaic art: a 44-by-15-foot carpet that covered the floor of a fifth- to seventh-century C.E. synagogue. The Sepphoris synagogue mosaic is remarkable […]

You have already read your free article for this month. Please join the BAS Library or become an All Access member of BAS to gain full access to this article and so much more.

Already a library member? Log in here.

Institution user? Log in with your IP address or Username

Endnotes

See “Mosaic Masterpiece Dazzles Sepphoris Volunteers,” BAR 14:01. Also see Mark Chancey and Eric M. Meyers, “How Jewish Was Sepphoris in Jesus’ Time?” BAR 26:04.

See Ehud Netzer and Zeev Weiss, “New Mosaic Art From Sepphoris,” BAR 18:06.

The excavation was conducted by the Institute of Archaeology at Hebrew University. Additional work was carried out in the synagogue area during the summers of 1994, 1996 and 1997. The first two seasons were directed jointly by Ehud Netzer and Zeev Weiss, while the last two seasons were conducted under the sole direction of Weiss. The photos of the mosaic were taken by Gabi Laron and the drawings are by M. Kaplan and Pnina Arad. Translation of the Greek dedication inscription was done with collaboration of Dr. Leah Di Segni. For more on the mosaic, see Weiss and Netzer, Promise and Redemption, A Synagogue Mosaic from Sepphoris (Jerusalem: Israel Museum, 1996); and Weiss and Netzer, “The Sepphoris Synagogue: A New Look at Synagogue Art and Architecture in the Byzantine Period,” in Eric M. Meyers, ed. The Galilee from Rabbinic to Medieval Times, (Winona Lake, IN: Eisenbrauns, 1999), pp. 199–226.

Eliezer L. Sukenik, “The Ancient Synagogue at Yafa Near Nazareth—Preliminary Report,” Louis Rabinowitz Fund Bulletin 2 (1951), pp. 6–24; Na’im Makhouly and Michael Avi-Yonah, “A Sixth Century Synagogue at Isfiya,” Quarterly of the Department of Antiquities in Palestine 3 (1934), pp. 118–131; Shimon Dar, “The Synagogue at Hirbet-Sumaqa on Mt. Carmel,” in Aaron Oppenheimer, Ciriel Kasher and Uriel Rappaport, eds., Synagogues in Antiquity (Jerusalem: Yad Izhak Ben Zvi, 1987), pp. 213–230 (in Hebrew).

Shmuel Safrai, “Was There a Women’s Gallery in the Ancient Synagogue?” Tarbiz 32 (1963), pp. 329–330 (Hebrew). In Ze’ev Safrai’s opinion, separation between men and women, and the consequent construction of women’s galleries, only began at the end of the ancient era. See Ze’ev Safrai, “Dukhan, Aron and Teva: How Was the Ancient Synagogue Furnished?” in Rachel Hachlili, ed. Ancient Synagogues in Israel, British Archaeological Reports, International Series 499 (Oxford, 1989), pp. 78–79.

Yoram Tsafrir, Eretz Israel from the Destruction of the Second Temple to the Muslim Conquest, Archaeology and Art (Jerusalem: Yad Izhak Ben Zvi, 1984), pp. 366–369 (in Hebrew).

Carl-Otto Nordström, “The Temple Miniatures in the Peter Comestor Manuscript at Madrid,” in Joseph Gutmann, ed., No Graven Images: Studies in Art and the Hebrew Bible (New York: Ktav, 1971), pp. 39–74.

See Yitzhak Magen, “Samaritan Synagogues,” Qadmoniot 25 (1993), pp. 70–72 (in Hebrew). See also Reinhard Pummer, “How to Tell a Samaritan Synagogue from a Jewish Synagogue,” BAR 24:03.