The Temple Menorah—Where Is It?

What is history and what is myth? What is true and what is legendary?

Reporting on his 1996 meeting with Pope John Paul II (1978–2005), Israel’s Minister of Religious Affairs Shimon Shetreet reported, according to the Jerusalem Post, that “he had asked for Vatican cooperation in locating the gold menorah from the Second Temple that was brought to Rome by Titus in 70 C.E.” Shetreet claimed that recent research at the University of Florence indicated the Menorah might be among the hidden treasures in the Vatican’s storerooms. “I don’t say it’s there for sure,” he said, “but I asked the Pope to help in the search as a goodwill gesture in recognition of the improved relations between Catholics and Jews.”1

Witnesses to this conversation “tell that a tense silence hovered over the room after Shetreet’s request was heard.”2 I tried to follow up on Shetreet’s reference to research at the University of Florence, but no one I contacted there had ever heard of it. This story has repeated itself a number of times since. One of the two chief rabbis of Israel, on their historic visit to the Vatican in 2004, asked about the Menorah, as did the President of Israel, Moshe Katzav, on another occasion. Asked for an official response, this is what I received from the Israeli Ministry of Foreign Affairs via e-mail:

The requests by Shetreet, the president, and the chief rabbis reflect the long-held belief that the Catholic Church, as the inheritor of Rome, took possession of the empire’s booty—as documented by the Arch of Titus. It is thus assumed that, among other treasures looted from the Jewish people, the Temple menorah is stashed away someplace in the storerooms of the Vatican.

This is not to say that 2,000 years or so have been enough time for the Foreign Ministry to formulate a policy on the matter. Unofficially at least, we look forward to the restoration of the treasures of the Jewish people to their rightful homeland, but do not anticipate this will occur before the coming of the Messiah.

These requests of the Church are a fascinating extension of the Jewish hope that the Temple Menorah taken by Titus would be returned “home.”

The legends of the Menorah at the Vatican have considerable currency. I have heard them from many Jews who take it as historical fact. In one version, a certain American rabbi entered the Vatican and saw the Menorah.3 In another version, it was an Israeli Moroccan rabbi known as “Rabbi Pinto” who saw it. In a third version, when former Chief Rabbi of Israel Isaac Herzog went to rescue Jewish children in Europe, he visited Pope Pius XII (1939–1958) at the Vatican.4 According to this story, the Pope showed Rabbi Herzog the Menorah, but refused to return it.

Father Leonard Boyle, former director of the Vatican Libraries, tells of Jewish tourists from the United States entering the library and, with all naiveté, telling Father Boyle that their rabbis had instructed them to find the Menorah during their visit.5

Folklorist Dov Noy tells me that the myth of the Menorah at the Vatican is not a part of traditional Jewish folklore. It is not recorded by the researchers of the Israel Folklore Archive. Apparently, it is a distinctly American-Jewish urban myth.

How this myth arose we have no idea. But it is interesting to compare it to the ancient sources regarding the Menorah following the Roman destruction of the Temple in 70 C.E.

The best-known evidence for the Temple Menorah in Rome is, of course, the monumental victory arch of Titus. This arch, completed in 81 C.E. after Titus’s death, was just one of the many triumphal arches and monuments that once graced the center of Rome. While large, more than 50 feet tall, it was a rather average-sized memorial two thousand years ago. The interior of the arch is carved with bas reliefs of Titus’s triumphal entry into Jerusalem on one side, the parading of the sacred vessels of the Jerusalem Temple into Rome on the other. These include the Table for Showbread, trumpets and, most prominently, the seven-branched Menorah of the Temple.

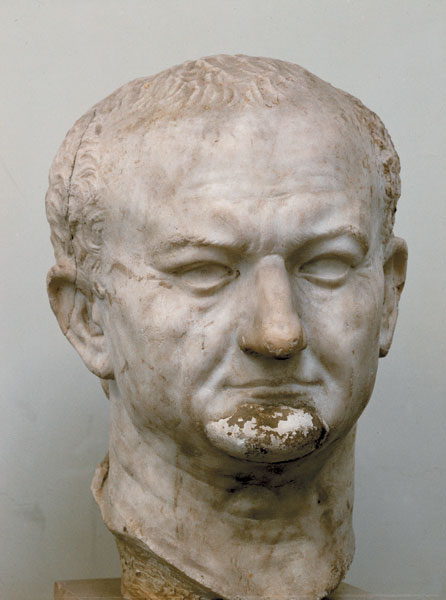

But the Arch of Titus isn’t the earliest reference to the Temple Menorah in Rome. The Jewish historian Josephus was in Rome and saw the triumphal celebration of Jerusalem’s defeat in Rome in 70 C.E. At the beginning of the revolt, Josephus had been the Jewish general in charge of the Galilee. In a famous turn about, he surrendered and joined the Roman side, writing books under Imperial patronage about the Jewish War and, at the same time, defending Jewish tradition. In general, Josephus’s descriptions of the architecture of ancient Judea have been found to be extremely accurate; his discussions of Jerusalem and of Masada are two examples. His work—written in the mode of Roman historiography—is always colored by his apologetic approach to both the Flavian emperors (Vespasian, Titus and Domitian) and on behalf of the Jews.

In the Jewish War6 Josephus describes how a certain Jewish priest named Phineas handed over to the Romans “some of the sacred treasures”:

Two menorot similar to those deposited in the sanctuary, along with tables, bowls, and platters, all of solid gold and very massive. He further delivered up veils, the high-priests’ vestments, including the precious stones, and many other articles for public worship and a mass of cinnamon and cassia and a multitude of other spices, which they mixed and burned daily as incense to God.

Josephus concludes his description by noting that “Those services procure[ed] for him [Phineas], although a prisoner of war, the pardon accorded to the refugees.”

Josephus also describes the Temple trophies in his account of the triumphal procession on Titus’s return to Rome from his successful campaign in Judea:

The spoils in general were borne in promiscuous heaps; but conspicuous above all stood those captured in the Temple at Jerusalem. These consisted of a golden table, many talents in weight, and a Menorah, likewise made of gold … After these, and last of all the spoils, was carried a copy of the Jewish Law. They followed a large party carrying images of victory, all made of ivory and gold. Behind them drove Vespasian [who initially led the Roman forces before he was proclaimed emperor in 69 C.E.], followed by Titus [who finally suppressed the rebellion]; while Domitian [his brother and future emperor] rode beside them, in magnificent apparel and mounted on a steed that was in itself a sight.

There is no reason to doubt the historicity of these descriptions and images, which are so close in content to the official visual portrayal of these events on the Arch of Titus. Note Josephus’s mention of the Showbread table (the Biblical “bread of the presence” [Exodus 25], which he refers to as the “golden table.” While in the service of the Temple, this table contained 12 loaves of unleavened bread, as an offering to God) immediately followed by mention of the Menorah. This pairing of the Menorah and the Showbread table, which follows the order in which these artifacts are described in Exodus 25 and elsewhere, is no doubt based on their adjacent locations within the Temple, as well as their physical impressiveness (each was manufactured using large quantities of gold).

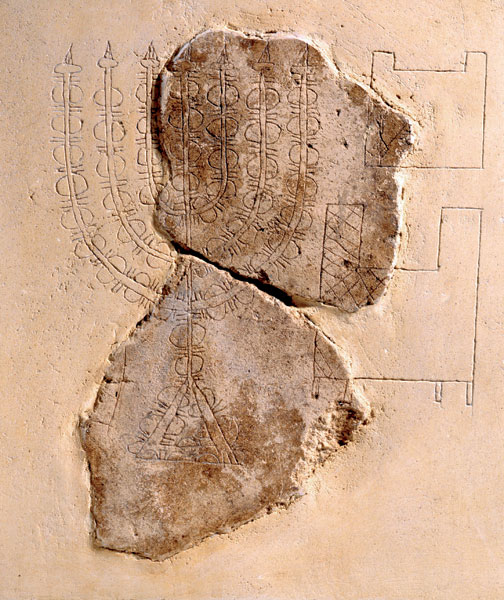

The Menorah and table were paired as early as 39 B.C.E. on a lepton coin of Mattathias Antigonos as an apparent propaganda tool to ward off the Roman-backed usurper Herod.7 The juxtaposition of the table and the Menorah is also found in a graffito on a plaster fragment discovered in excavations in the Jewish Quarter in Jerusalem dating to just before the Roman destruction of the city in 70 C.E.a

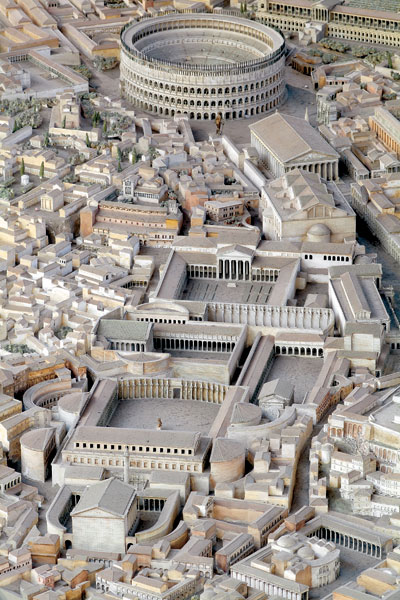

Josephus writes that the Temple trophies were displayed in Rome after the procession. According to him, they were exhibited in the magnificent Temple of Peace. Begun in 71 and completed in 75 C.E., this temple was built by Vespasian to commemorate the Roman defeat of Judea and was later rebuilt by Domitian. Pliny the Elder includes the Temple of Peace among Rome’s “noble buildings,” describing it as one of “the most beautiful [buildings] the world has ever seen.”8 It was built on the southern side of the Argilentum—a major road connecting the Subura (Suburb) to the Forum. The complex included a pleasure garden and a library. A model in the Museum of the City of Rome (shown opposite) suggests what the Temple of Peace might have looked like.

Here is how Josephus describes it:

The triumphal ceremonies being concluded and the empire of the Romans established on the firmest foundation, Vespasian decided to erect a Temple of Peace. This was very speedily completed and in a style surpassing all human conception. For, besides having prodigious resources of wealth on which to draw, he also embellished it with ancient masterworks of painting and sculpture; indeed, into that shrine were accumulated and stored all objects for the sight of which men had once wandered over the whole world, eager to see them severally while they lay in various countries. Here, too, he laid up the vessels of gold from the temple of the Jews, on which he prided himself.9

Jews, both natives of Rome and visitors, no doubt came to the Temple of Peace to view the Temple items—as Jews to this day still flock to the Arch of Titus. The temple was a partially public space, as the White House is in the United States. As the great Roman architect Vitruvius notes, in homes of the powerful “the common rooms are those into which, though uninvited, persons of the people can come by right, such as vestibules, courtyards, peristyles and other apartments of similar uses.”10

Thus it seems that the sacred vessels were deposited and on view within Vespasian’s palace during the latter first century.

The traditions of the earliest Rabbis (the Tannaim [second century C.E.]), preserves several accounts of sightings of the holy vessels in Rome. For example, one mid-second century Rabbi claims to have seen the parokhet, or veil covering the Ark of the Covenant:

Rabbi Lazer son of Rabbi Jose said, “I saw it [the parokhet] in Rome and there were drops of blood on it. And they told me:11 ‘These are from the drops of blood of the Day of Atonement.’”12

The enigmatic concluding sentence of this quotation seems to suggest that many had seen the veil and that there was some sort of local tradition about it. One can almost imagine Rabbi Lazar going to see the parokhet and discussing the bloody spots with local Jews. In another tradition, this same rabbi is said to have seen the priestly breastplate worn in the Temple:

“I saw it [the priestly breastplate of gold] in Rome, and the name was written on it in a single line, ‘Holy to the Lord.’”13

Still another rabbi saw the Menorah itself: Rabbi Simeon said, “When I went to Rome there I saw the Menorah.”14

These sightings have a reasonable chance of recording reliable history. The items mentioned could well have been viewed in Rome by these second-century rabbis. Even if we are inclined to dismiss these Rabbinic sources as mere literary devices or as folklore, the external evidence from Josephus and from the Arch of Titus lend strong support for their historicity.

It is interesting to compare the evidence for these sightings with other less reliable accounts, accounts that we must regard as literary and not as historical. For example, a midrashb known as Esther Rabba tells how the throne of Solomon was taken to Babylon by Nebuchadnezzar when he destroyed the First Temple in 586 B.C.E. From there it went to Medea, then to Greece, then to Edom—and, the text continues, “Rabbi Eleazar son of Rabbi Jose said: ‘I saw its fragments in Rome.’”

Another sighting in Rome involved the brain of the hated Titus, who commanded the Roman troops that destroyed Jerusalem. According to this story, Titus’s brain was enlarged by mosquito bites so that it was as large as a two-pound dove. It is a marvelous story (printed in the box), but of course it is not to be taken as an historical account (though it does provide a powerful narrative response, returning God and his enduring covenant to center stage). By contrast, the other stories previously cited, involving the Temple treasures from the Second Temple, do have the ring of authenticity.

A Byzantine-period rabbinic collection notes that Temple artifacts had been taken to Rome and were “hidden away.” The objects include “the [Showbread] table, the Menorah, the veil of the Ark and the vestments of the anointed priest.”15 In the second half of the 12th century a Spanish Jew known as Benjamin of Tudela made a tour of the then-known world (he went as far east as Mesopotamia) and kept

a travel diary in which he claims to have seen a church with two columns from Solomon’s Temple in Rome. More pertinent to the present discussion, he was apparently told by Rome’s Jews that the Temple vessels that had been brought to Rome were hidden in a cave in the church:

In the church of St. John in the Lateran there are two copper columns that were in the Temple, the handiwork of King Solomon, peace be upon him. Upon each column is inscribed “Solomon son of David.” The Jews of Rome said that each year on the Ninth of Av [the traditional date on which both the First and Second Temples were destroyed, first by the Babylonians and then by the Romans] they found moisture running down them like water. There also is the cave where Titus the son of Vespasian hid away the Temple vessels which he brought from Jerusalem.16

If nothing else, this suggests that medieval Roman Jews had a tradition that the Temple vessels were in Christian hands. A century later Christians made the same claim. A mosaic in an apse in Saint John in the Lateran from 1291 contained an inscription proclaiming the presence not only of the Ark of the Covenant but of the Menorah and columns: “Titus and Vespasian had this ark and the candelabrum and … the four columns here present taken from the Jews in Jerusalem and brought to Rome.” By the end of the 13th century, then, the Lateran was claiming to have the Temple booty of the Solomonic Temple, taken anachronistically by “Titus and Vespasian” and on display (or in a reliquary). Though neither Christians nor Jews could actually see the Menorah, its presence was intense.17

When contemporary Jews go to Rome, the Menorah is no less present—yet non-present. They know that their holy vessels were brought to Rome, as commemorated in that open sore known as the Arch of Titus. They can also see the Menorah in the remains of the fourth-century Jewish catacombs of Rome, most of which are safely stored and displayed in the Vatican. If the Vatican did have the actual Menorah and other vessels, there is no reason to think that in our more ecumenical age they would not display them, just as they do so many fine Jewish manuscripts and artifacts. I could imagine the Menorah under a huge cupola resting on a base, surrounded by a velvet cord with an Italian guard on either side. As long as Jews believe that the Menorah is in Rome, awaiting return to Jerusalem, however, the hope of restoration is not yet lost.

MLA Citation

Footnotes

See Nitza Rosovsky, “A Thousand Years of History in Jerusalem’s Quarter,” BAR, May/June 1992.

Endnotes

Lisa Palmieri-Billig, “Shetreet: Pope Likely to Visit Next Year,” Jerusalem Post January 18, 1996, p. 1.

Ronan Bergman, “Ha-Otzrot ha-Yehudiim shel ha-Apifior,” Mussaf Haaretz, May 15, 1996, pp. 18–20, 22 (Hebrew).

Jewish War 6, 387–391. Translations of Josephus follow, for the most part, Josephus Flavius, The Complete Works, trans. Henry St. John Thackery, Ralph Marcus, Allen Wikgren and Louis Feldman (Cambridge, MA and London: Harvard Univ. Press, 1961–1965).

Pliny, Natural History 36, 102, trans. D.E. Eicholz, Loeb Classical Library (Cambridge, MA: Harvard Univ. Press, 1962).

Vitruvius, On Architecture 6.5.1, trans. F. Granger, Loeb Classical Library (Cambridge, MA: Harvard Univ. Press, 1934).

Tosefta Kippurim 2:16; The Tosefta, ed. Saul Lieberman, 2nd ed. (New York: Jewish Theological Seminary, 1992).

Jerusalem Talmud, Yoma 4:1, 41c; Talmud Yerushalmi According to Ms. Or. 4720 (Scaql. 3) of the Leiden University Library with Restorations and Corrections (Jerusalem: Academy of the Hebrew Language, 2001).

Sifre Zutta, Be-ha’alotkha to Numbers 8:2; Sifre D’Be Rab and Sifre Autta on Numbers ed. H.S. Horowitz (Jerusalem: Wahrmann, 1966) = Midrash ha-Gadol, ed. Z.M. Rabinowitz (Jerusalem: Rav Kook Institute, 1967).

Avot D’Rabbi Nathan, ed. S. Schechter (New York: Jewish Theological Seminary, 1997), version A, ch. 41, p. 133.