Israel not only survived but thrived in exile. Indeed, Israelite Yahwisma became universal monotheism in the Babylonian Exile.

In the preceding article, Professor Seymour Gitin explains why the Philistines, unlike the Israelites, did not survive the Babylonian Exile, although their cities were destroyed by the same Babylonian ruler, Nebuchadnezzar, who destroyed Jerusalem and burned the Israelite Temple. Professor Gitin suggests that culture made all the difference. Perhaps so, but I think we can be more specific in the case of the Israelites.

One factor in Israel’s survival was that her religious leadership appears to have followed her people into exile. Ezekiel, for example, was both priest and prophet (Ezekiel 1:3). He answers questions of the elders, the traditional leaders and heads of the community, who gathered around him (Ezekiel 8:1; 14:1; 20:1). The Israelite community thus retained its religious structure.

Equally important, the Israelite exiles, like other exiled peoples in Babylonia, appear to have been largely aggregated in their own communities. From ancient cuneiform texts found in Babylonia, especially in Nippur, we learn of communities of deportees living in towns with names like Ashkelon and Gaza (no doubt the Philistines), Tyre (the Phoenicians) and Kedesh.1 These settlements should perhaps more appropriately be called New Ashkelon and New Gaza and New Tyre and New Kedesh, just as we have New York and New Amsterdam before it (although not peopled by forced exiles). This is now well known from several economic and administrative documents, as well as a few letters.2

That the Israelites also lived in their own communities can already be deduced from passages in Ezekiel. As already noted, the exiles kept their own traditional leaders, the “elders,” who consult the prophet living among them.

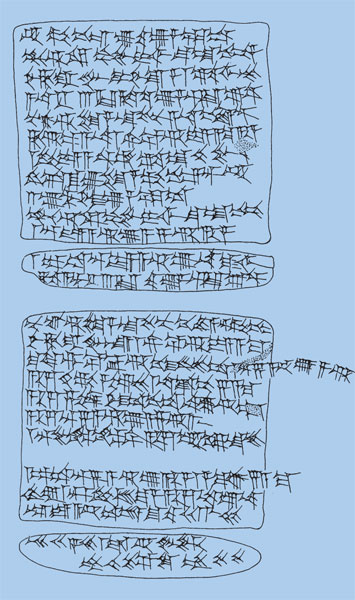

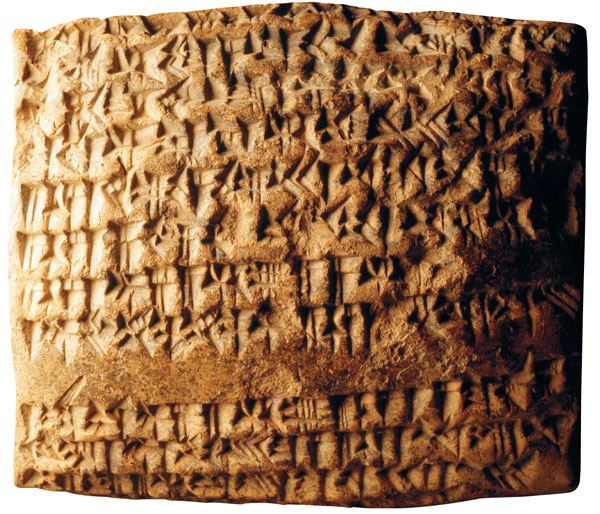

More recently, a cuneiform tablet dated 498 B.C.E. has surfaced that was written at a place called al Yahudu, “the town of Judah” or “the Judahite Town.”3 Names mentioned in this tablet include Neri-Yama (=Neri-Yahu; Yahu is a theophoric element, a form of Yahweh), Yahu-azari and Abdu-Yahu—clearly Judahite Yahwist names. The place name “the Judahite Town” can only mean Jerusalem, for that is the name it is called in Neo-Babylonian chronicles. For example: “Year 7, 598–597 B.C.E.: in Kislev the king of Babylonia called out his army and marched to Hattu. He set his camp against the city of Judah [Ya-a-hu-du] and on 2 Adar he took the city and captured the king …”4 The “City of Judah” is clearly a reference to Jerusalem. Similarly in the new tablet, the reference to the “the Judahite town” (or the city of Judah) is Jerusalem, but not the Jerusalem in what had been Judah, but the New Jerusalem in Babylonia.

This regrouping of Jerusalemite deportees, including priests and prophets, undoubtedly facilitated the continuation of the culture and religion from which the deportees came. It also provided a community structure that could address the religious crisis that must have confronted the exiled community of Israelites. That there was a serious religious crisis seems obvious. In exile the Judahites were daily confronted with the prestige and popularity of the victorious Babylonian gods—Marduk, Ishtar and Nabu, to name only a few. The temples to these Babylonian deities graced Babylonian cities, reflecting the economic prosperity and power of those who worshiped these gods. And what of Yahweh, whose house lay in ruins in Jerusalem? Indeed, it was the only house where he would be legitimately propitiated ever since the late-eighth-century B.C.E. reform of Hezekiah and the seventh-century B.C.E. reform of Josiah, which centralized worship of Yahweh in the capital.

The initial response of Ezekiel was consistent with the warnings Jeremiah had given (Jeremiah 5:11–18; 6:6–8; 7:1–15, esp. 13–14: “Though I took pains to speak to you, you did not listen, and though I called, you gave no answer. Therefore what I did to Shiloh I will do to this house [the Temple] which bears my name …”). Now the warning had come to terrible fruition. The catastrophe that had struck was the result, however, not of the impotence of Yahweh, but rather of the repeated disregard by the Israelites of his commandments: “I will judge you according to your ways and punish you for all your abominations” (Ezekiel 7:8).

At the same time, Ezekiel looks for a revival of Yahwism among the remnant in Babylon. Yahweh, who before the Exile had “put his name” in Jerusalem, became not simply the God of Israel, but a moving, ambulant God, who appears to the prophet in Babylonia. The divine presence has left Jerusalem. Ezekiel 1 describes the prophet’s call with complex and vivid imagery. Ezekiel tells us that he is living “among the exiles by the Chebar River” when he received the call (Ezekiel 1:1). The important point here is that he received the call from the Lord in Babylonia. What he saw was “the appearance of the likeness of the glory of Yahweh” (Ezekiel 1:28). Yahweh is no longer confined to his house in Jerusalem. He now appears in the New Jerusalem—close to the Chebar River (see also, to the same effect, Ezekiel 10:20–22). Yahweh is active everywhere his people reside. He is in the process of becoming a universal God.

Perhaps this transformation was affected by the fact that the Babylonians apparently pardoned King Jehoiachin, the Judahite king who had been carried off to exile in Nebuchadnezzar’s incursion into Judah in 597 B.C.E., 11 years before the Babylonian monarch invaded again and destroyed Jerusalem and burned the Temple. After 37 years, however, Jehoiachin was released from prison and apparently pardoned. He then supped regularly at the Babylonian king’s table and lived off a stipend from the monarch (2 Kings 25:27–30; Jeremiah 52:31–34). Four cuneiform texts, found in a palace in Babylon and dating from before Jehoiachin’s release, confirm the presence of “Jehoiachin king of Judah” among the people receiving rations of oil.5

And what of the Babylonian gods? The anonymous prophet known to scholars as Deutero-Isaiah or Second Isaiah, who lived in Babylonia and wrote about a half-century after Ezekiel (Second Isaiah’s oeuvre is preserved in Isaiah 40–55), describes these Babylonian gods:

An idol? A workman casts it and a goldsmith overlays it with gold, and casts for it silver chains. As a gift one chooses mulberry wood—wood that will not rot—then seeks out a skilled artisan to set up an image that will not topple … All who make idols are nothing, and all the things they delight in do not profit … Bel bows down. Nebo stoops. Their idols are on beasts and cattle; these things you carry are loaded as burdens on weary animals (Isaiah 40:19–20; 44:9; 46:1).

For Ezekiel, the gods of Babylonia are nothing but “wood and stone” (Ezekiel 20:44).

The rejection of iconic worship as practiced in Babylonia, with its many statues of divinities and its abundant rituals, becomes a traditional motif of Israelite prophetic preaching and literature (see, for example, Deuteronomy 4:28).

But if the gods of Babylonia are only the product of human technical skill, what happens to Yahweh?

Yahweh is no longer connected to the territories of Israel and Judah and to his Jerusalem Temple, but is now a God living among his people even if they are in exile. Soon, he will be no longer primarily “God of Israel,” but a universal God for all peoples. In this way Yahwism adapted to the conditions of the Judahites exiled in Babylonia. The single divine character of Yahweh and his universal power was increasingly clearly asserted by the prophets. As Second Isaiah declares:

Before me no god was formed,

Nor shall there be any after me …

I am the first and I am the last;

Beside me there is no god …

All who make idols are nothing

(Isaiah 43:10; 44:6, 9).

While Yahweh’s creative role is not new, it is emphasized anew: “I made the earth, and created humankind upon it; it was my hands that stretched out the heavens, and I commanded all their host” (Isaiah 24:12).

Yahweh is no longer limited only to the people of Israel; other peoples too must recognize him as the only true God.

In this spirit, redactors reedited and republished the great Deuteronomic History (Joshua, Judges, Samuel and Kings), originally edited in the seventh century B.C.E., so that it now reflected these new understandings, largely developed in the Exile (see, for example, Deuteronomy 4:35, 39; 1 Kings 8:60).

Universal monotheism was thus firmly established in Israelite tradition.

MLA Citation

Endnotes

James B. Pritchard, ed., Ancient Near Eastern Texts Relating to the Old Testament (Princeton: Princeton Univ. Press, 1969), p. 308.

Israel Eph’al, “The Western Minorities in Babylonia in the Sixth-Fifth Centuries B.C.: Maintenance and Cohesion,” Orientalia 47 (1978), pp. 74–90, esp. 80–81; F. Joannès, “La localisation de Surru à l’époque néo-babylonienne,” Semitica 32 (1982), pp. 35–43; Ran Zadok, “Geographical Names According to New and Late-Babylonian Texts,” Repertoire Geographique des Textes Cuniformes 8 (Wiesbaden, Germany: Harrassowitz, 1985), pp. 158, 183, 229, 250, 300.

Joannès and André Lemaire, “Trois tablettes cunéiformes à onomastique ouest-sémitique (collection Sh. Moussaïeff),” Transeuphratène 17 (1999), pp. 17–34, esp. pp. 17–27.

Alan Millard, “The Babylonian Chronicle,” in William W. Hallo, ed., The Context of Scripture, vol. 1 (Leiden/Boston: Brill, 2003), pp. 467–468, esp. 468.