The Wise Woman of Abel Beth Maacah

026

In a world dominated by men, and at a time that saw Israel’s greatest monarch—King David himself—rule over the land and assert his dominance over any and all who might challenge him, it was a woman—a Wise Woman—in the town of Abel Beth Maacah who stood up, stared down the commander of David’s army, and successfully negotiated her city’s salvation. This is her story.

As archaeologists who focus on the period of the Old Testament, we naturally included an examination of what the Bible has to say about the site in our preparations for the exciting new excavations at Tel Abel Beth Maacah back in 2013.1 This large, prominent mound in the far north of Israel commands major roads running through the fertile Hula Valley and is set on the Iyyun River, one of the headwaters of the Jordan River. The tell strategically occupies the border between modern Syria, Lebanon, and Israel, mirroring the 028ancient border between Aram, Phoenicia, and Israel for most of the Iron Age (1200–721 B.C.E.). Given its strategic placement, we were certain that it would appear in multiple passages. However, we were surprised to see that, in fact, Abel Beth Maacah is mentioned only three times in the Bible.

The first two references were in relation to conquests: in 1 Kings 15 by the Aramean king Ben Hadad and in 2 Kings 15 by the Assyrian king Tiglath-Pileser III. The third reference, however, more than makes up for these rather dry military conquest lists.

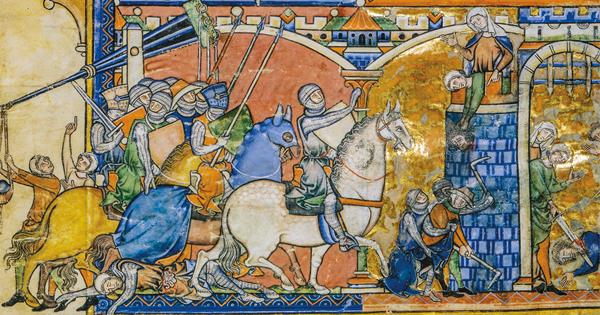

In 2 Samuel 20:14-22 we read about Sheba ben Bichri, a Benjaminite (who apparently lived in Mt. Ephraim) who rebelled against King David and fled the length of the country to take refuge at Abel Beth Maacah. None other than Joab, David’s chief of staff, and his army pursued the rebel. The pinnacle of this story comes during Joab’s siege and imminent destruction of the town, when a Wise Woman (Hebrew: חכמה אישה) appears and fearlessly approaches Joab:

“Listen! Listen! Please tell Joab, ‘Come here, I want to speak to you.’?” He came near her, and the woman said, “Are you Joab?” He answered, “I am.” Then she said to him, “Listen to the words of your servant.” He answered, “I am listening.” Then she said, “They used to say in the old days, ‘Let them inquire at Abel,’ and thus they settled things. I am peaceable—faithful to Israel. You seek to destroy a city and a mother in Israel. Why will you swallow up the heritage of the Lord?”

(2 Samuel 20:16–19, editor’s translation)

A curious and rather sheepish Joab declares that he doesn’t seek to destroy the city, but only wants to catch the rebel: “Far be it from me—far be it—that I should swallow up or destroy! This is not the case! But a man of the hill country of Ephraim, named Sheba son of Bichri, has lifted up his hand against 029King David. Give him up alone, and I will withdraw from the city” (2 Samuel 20:20–21).

Without hesitation, the Wise Woman of Abel Beth Maacah advises her townsfolk to end the saga: “The woman said to Joab, ‘Watch, his head will be thrown over the wall to you.’ Then the woman went to all the people with her wise plan. And they cut off the head of Sheba son of Bichri and threw it out to Joab” (2 Samuel 20:21-22).

And thus, she saves her town—and provides us with a plethora of material to examine, both textually and archaeologically.2 For instance, the text describes a siege ramp that Joab builds against the city wall. Perhaps we can find evidence of the siege or the city wall in the archaeological record. But we want to ask a different question: Can we look for the Wise Woman herself “in the dirt”? What kind of evidence could the story described in 2 Samuel 20 leave behind? (Aside from finding a headless body, of course!)

To start our search, we must first try to understand what a “Wise Woman” was and what role she played in Israelite society. What kind of wisdom is referred to—legal? cultic? spiritual? Are such roles solely allocated to women? Our Wise Woman remains anonymous; she is not named beyond her 030title. Was that enough to identify her in the eyes of the readers? Additionally, what was the source of her wisdom and its apparent attendant authority? After all, Joab, the mighty general, pays due respect to her. Is she a civic or cultic official appointed by a central authority, or is she operating by dint of a tradition embedded in the local community?

Another question we may ask is whether the phenomenon of wise women in the Bible is time-specific (in our case, the Iron Age IIA [950–830 B.C.E.]), or is this a long-lived tradition that goes back to the proto-Israelite or even Canaanite period, and does it continue into later periods?

Our first step is to compare our Wise Woman to other such figures in the Bible. The other so-named Wise Woman comes from Tekoa (2 Samuel 14). She, too, is anonymous and plays a crucial role in changing the turn of events related to rebellion against the kingship of David (in her case, the return of the rebel son Absalom to his father’s favor). She demonstrates adroitness in manipulating the situation to achieve her goal and certainly comes across as a person of wisdom and authority. However, as opposed to the Wise Woman of Abel Beth Maacah, the Wise Woman from Tekoa had her speech to David more or less dictated to her by Joab, making her more of an emissary than a proactive figure.

Another prominent woman of authority is the prophetess Deborah, who is also called a judge (Judges 4:4–5). Deborah is not an anonymous figure by any means and operates as a civic and military leader. She is referred to as a “mother in Israel” (Judges 5:7), recalling the extraordinary epithet used by the Wise Woman of Abel Beth Maacah when she admonished Joab, “You seek to destroy a city and a mother in Israel” (2 Samuel 20:19).

Other biblical women who are associated with public roles and who remain anonymous are often found practicing divination and acting as mediums or necromancers. The most famous of these is the “witch” of Endor who (surprisingly) conjures up the prophet Samuel for King Saul (1 Samuel 28). Women also fill the roles of celebrating or 031encouraging military victories with song and dance (such as Jephthah’s daughter, see Judges 11:30–31) and professional mourning (e.g., the “wailing women” in Jeremiah 9:17). Such practices were more in the realm of folk religion, and, as such, it seems that their roles were somewhat different from that of the Wise Woman of Abel Beth Maacah, whose actions played out on a civic level of leadership.

Adroit at diplomacy and knowledgeable of accepted wisdom, wise women apparently functioned like authoritative military leaders or prophets within their communities—when necessary.3 The anonymity of the wise women in the Bible seems to confirm that when this term was used, it evoked a culturally accepted role in the community that removed the need for further description. It is also clear that wise women operated locally, and we can assume these local venues served as central places for the resident population. On the other hand, their reputation was renowned enough to convince a king and a general to heed them, reflecting the importance and resonance of their role in early Israelite society.

Three salient points about these influential Israelite women and their operations emerge: (1) Traditions place them in the early part of national and religious development, during the pre-monarchic and early monarchic periods; (2) they operated in the more peripheral regions and towns or villages, removed from the eventually established urban capitals of the kingdoms of Israel and Judah in Samaria and Jerusalem; and (3) their authority and influence were well entrenched in the social and cultural fabric of early Israelite society and stemmed from local traditions rather than official appointment.

The Wise Woman of Abel Beth Maacah makes three intriguing statements. Both enigmatic and informative, all three play a role in understanding the archaeological finds at the site: The first is her reference to “a city and a mother in Israel” (2 Samuel 20:19). Another is the cryptic “They used to say in the old days, ‘Let them inquire at Abel,’ and thus they settled things” (2 Samuel 20:18). The third is her statement “I am peaceable—faithful to Israel” (2 Samuel 20:19).

Many scholars have pondered the meaning of the phrase “a city and a mother,” which appears in the Bible only in this instance. Deborah is called “a mother in Israel,” which is somewhat different. One interpretation assumes that the city itself is the mother, which is also reflected in the translation of this phrase in the Septuagint as “metropolis” (Greek: μητρόπλɩς), a term still used to describe a major urban center. This identification of the city as a mother is reflected in the concept of the “city and its daughters” (e.g., Joshua 17:11), describing an urban center that controlled satellite settlements; the satellites are the “daughters,” and the city is the “mother.”

Another interpretation sees the Wise Woman herself as the mother. Thus, when she admonishes Joab for wanting to destroy a “city and a mother in Israel,” she means that he wants to do damage to both the physical city and to herself, as she is the “mother,” although not in a biological sense but rather as a matriarch.

Many scholars think that “mother” is used in the sense of an oracle or an augur. This association of “mother” and “oracle” might enlighten one of the other statements made by the Wise Woman: “They 032used to say in the old days, ‘Let them inquire at Abel,’ and thus they settled things,” which alludes to it having been a long-lived local center for divination. Either way, the idea of Abel Beth Maacah as having a reputation for wisdom and faithfulness to the tradition of Israel sits well with the role of the Wise Woman as a local figure of authority and influence operating in this particular city, which served as a regional center for both political leadership and, possibly, cult-related activity.

The meaning of “mother” as oracle is possibly paralleled in the term found in Judges 18:19, wherein the tribe of Dan cajoles the prophet Micah to accompany them on their journey northward and become their “father and priest” in the city of Dan. The biblical tradition of Dan in the tenth century B.C.E. describes an important cultic center established there by Jeroboam I (1 Kings 12:26-30). Archaeological excavations conducted by Avraham Biran revealed a rich complex with a large four-horned altar, a platform, and a building identified as priestly chambers, including cultic paraphernalia, such as incense shovels and small altars. The date of this complex is debated (as is the national affinity of the town as Israelite or Aramean), and some scholars tend to place it no earlier than the eighth century B.C.E., established during the reign of Jeroboam II. The lack of full publication of this context makes it difficult to securely confirm the date (or the national affinity).

Regardless of its precise dating, the existence of the tradition of Dan as a local cultic center is intriguing for our purposes in light of the possibility that the Wise Woman of Abel Beth Maacah filled the role of “oracle,” especially since the wording of 2 Samuel 20:18—“In the past they would always say, ‘Let them inquire in Abel,’ and that is how they settled things”—in the Septuagint includes an additional reference to Dan as well! The Septuagint’s version of 2 Samuel 20:18 reads, “Of old time they said thus, ‘Surely one was asked in Abel and Dan, whether the faithful in Israel failed in what they purposed.’?”

Could it be that the “mother” of Abel Beth Maacah and the “father” of Dan reflect the existence of a region famous for oracular activity during most of the Iron Age (1200–721 B.C.E.)?

Regarding the Wise Woman’s statement that the city has always been “peaceful and faithful in Israel” (2 Samuel 20:19), some scholars have understood the reference “faithful in Israel” to mean literally that Abel Beth Maacah had an allegiance to King David’s court in Jerusalem. This would explain why the Wise Woman and Abel Beth Maacah’s residents so readily handed over the rebel Sheba’s head to Joab.

Now we look at whether the archaeological data from our excavations at Tel Abel Beth Maacah can help contextualize the world of the Wise Woman. Six seasons of excavation at Abel Beth Maacah have 033yielded rich finds from the second and first millennia B.C.E. The finds dating to the Iron Age I (1200–950 B.C.E.) and IIA (950–830 B.C.E.) are particularly intriguing and help us better understand this important yet little-excavated border region.

Just at the time when nearby Hazor, formerly the “head of all those kingdoms” (Joshua 10:11), lay in ruins and was only sparsely occupied, and Dan was apparently a large village, our excavations revealed that Abel Beth Maacah flourished as a well-built urban center—during the 12th and 11th centuries B.C.E. (Iron Age I). A dense occupation sequence with domestic, cultic, and public buildings spans this period on the mound. We uncovered an intriguing late 12th-century structure with a rounded wall and many standing stones (masseboth) that we interpret as a small cultic building.

We also found a large, well-built public complex belonging to the latter part of the 11th century B.C.E. (late Iron Age I) with evidence of bronze and iron working, large-scale storage, and cultic activity. Its violent destruction has been dated by carbon 14 to the tenth century B.C.E. This complex has a large space that apparently was devoted to some ritual activity. It contains benches, a stone offering table, basins, a cult stand, and a unique plastered clay installation topped with a double “sink” with a drain.

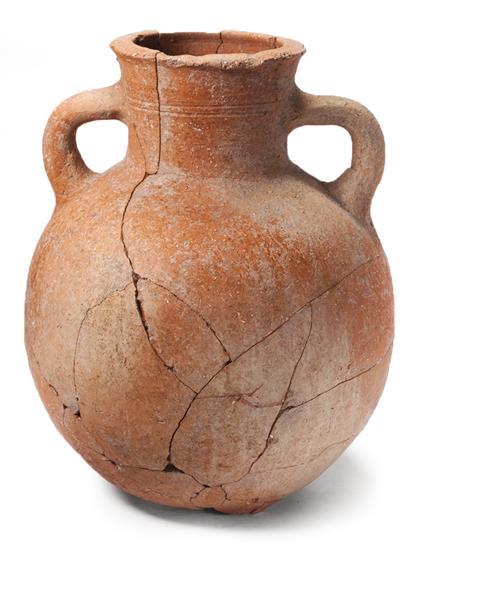

Following the fiery destruction of this large complex, an entirely new structure was built, following a different building plan, but still of a substantial nature, evidenced by its sturdy stone walls, floors, and installations. This new structure dates to the late tenth and ninth centuries B.C.E. (the Iron Age IIA).4 One of its striking features is an extensive and finely laid stone pavement, possibly in an open courtyard. On one end of this pavement was a raised round “podium” built of brick and stone, on top of which lay a complete amphora jar that held 425 astragali. An astragalus is an animal’s talus, or ankle bone; such bones are found throughout the ancient Near East, as well as in Greece and other regions. Although such bones are common in many excavations, it is quite unusual to find such a large collection. The bones in our astragali pot are of sheep, goats, and deer—but none of cattle or pigs.

What purpose did these astragali serve? Scholars offer different explanations: They may have been used as game pieces, or they may have been used in ritual activities, such as divination, as well as in political advisory. While it is, of course, possible that the Abel Beth Maacah astragali were a kind of “Toys ‘R’ Us” in a pot, it seems more likely that such a large collection stored carefully in a finely made vessel and placed on a raised podium in a large public courtyard served a ritual purpose—although we do not yet know exactly what that purpose was. We can point out that the stone pavement on which the astragali pot’s podium was set is located above (and slightly to the west of) the late Iron I context with the ritual-related paraphernalia, which may suggest continuity of cultic activity here.

The actions and role of the Wise Woman of Abel Beth Maacah serves as an important window into the status and impact of women in early Israelite society. For the most part, scholars have recognized the source of female empowerment as stemming from prominence in the household, especially in the realms of nutrition and child-rearing, controlling household crafts and organization, as well as domestic religion. The actions of the Wise Woman were different, having been conducted outside the household in the public sphere. Women filled this authoritative political role in Israel’s pre-monarchic days when society was more egalitarian and political power was distributed among tribes and villages. Although wise women also appear in biblical texts during the early days of the Israelite monarchy, the role seems to vanish later in the Iron Age—after the monarchy becomes more centralized and established.5

Interestingly, wise women (sometimes termed “old women”) are also mentioned in Late Bronze Age (1550–1200 B.C.E.) Hittite texts as ritual experts who operated based on folk knowledge, practicing a range of divinatory and magical tasks, which included fertility rites, healing, and protection against plague or other misfortunes. Although our Wise Woman herself was not necessarily a divinator or spiritual leader, tradition places her in a town—and a nearby region, if we add Dan, as the Septuagint and the archaeological evidence do—characterized as having a long reputation for wisdom and faithfulness to the tradition of Israel. This long-standing tradition of “inquiry” at Abel Beth Maacah, perhaps a center of an oracle, might have been one of the sources of her authority, as was her wisdom itself.

The highly developed and well-planned Iron Age I complex excavated at Abel Beth Maacah that was destroyed in the tenth century B.C.E., as well as the rebuilt substantial city of the subsequent Iron Age IIA, serve as an appropriate backdrop of a regional center that could have housed a figure of wisdom and local authority, such as the judicious and brave Wise Woman.

In a world dominated by men, and at a time that saw Israel’s greatest monarch—King David himself—rule over the land and assert his dominance over any and all who might challenge him, it was a woman—a Wise Woman—in the town of Abel Beth Maacah who stood up, stared down the commander of David’s army, and successfully negotiated her city’s salvation. This is her story. As archaeologists who focus on the period of the Old Testament, we naturally included an examination of what the Bible has to say about the site in our preparations for the exciting new excavations at […]

You have already read your free article for this month. Please join the BAS Library or become an All Access member of BAS to gain full access to this article and so much more.

Already a library member? Log in here.

Institution user? Log in with your IP address or Username

Endnotes

1. We dedicate this article to the many wonderful “wise women” on our field and research staff who have contributed so much to the Tel Abel Beth Maacah excavation project: Dianne Benton, Ruhama Bonfil, Ortal Haroch, Christin Johnson, Carroll Kobs, Miriam (Mimi) Lavi, Fredrika Loew, Claire MacKay-Glasgow, Jennifer Maidrand, Ora Mazar, Lauren Monroe, Alla Rabinovich, Melissa Rosensweig, Bettina Schwarz, and many others, as well as to the many dedicated volunteers (female and male) who make our work possible. The Tel Abel Beth Maacah excavations are directed by Robert Mullins of Azusa Pacific University and Naama Yahalom-Mack and Nava Panitz-Cohen of The Hebrew University of Jerusalem. Excavation licenses are granted by the Israel Antiquities Authority and the Israel Nature and Parks Authority. This research was supported by the ISRAEL SCIENCE FOUNDATION (Grant No. 859/17).

2. The date of 2 Samuel 20 has been extensively discussed by many scholars, and some place Sheba ben Bichri’s rebellion in the eighth century B.C.E. It should be mentioned that our excavations at Tel Abel Beth Maacah to date have not identified an occupation stratum that can be clearly dated to this time or any destruction layer that can be attributed to Tiglath-Pileser III (as in 2 Kings 15). However, some pottery from the eighth century B.C.E. has been recovered in survey and debris.

3. Claudia V. Camp, “The Wise Women of 2 Samuel: A Role Model for Women in Early Israel?” The Catholic Bible Quarterly 43.1 (1981), p. 24.

4. Also dating to this period is a large casemate building on the upper part of the tell that contained several special finds, including an exquisite head of a bearded male made of faience. See Naama Yahalom-Mack, Nava Panitz-Cohen, and Robert Mullins, “From a Fortified Canaanite City-State to ‘a City and a Mother’ in Israel: Five Seasons of Excavation at Tel Abel Beth Maacah,” Near Eastern Archaeology 81.2 (2018), p. 154.

5. Camp, “Wise Women,” pp. 14, 26.