I believe I may have discovered the world’s earliest poorbox—a tangible expression of Israel’s ancient concern for the needy among its people.

On one of my frequent visits to Jerusalem’s Rockefeller Museum, I noticed an object that I had seen many times before in one of the cases: a pottery bowl with an inscription. It had been unearthed long ago—in fact, 80 years ago, during the 1911–1912 excavations at Beth Shemesh in the Shephelah, the lowland west of Jerusalem, in a dig headed by the British archaeologist Duncan Mackenzie.1 But this time I decided to study it anew because of my interest in the connections between ancient inscriptions and the shapes of the objects upon which they are inscribed.

The bowl has a typical Judean form, easily datable to the late eighth century B.C.E.a It is 7.5 inches across the top, reddish in color, burnished (rubbed to make the surface smooth and to eliminate the porosity of the surface), with lighter-red or pink concentric parallel lines on the inside. Many examples of this type of bowl were found in the ruins of level III at nearby Lachish, destroyed by Sennacherib in 701 B.C.E.

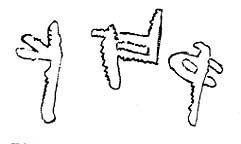

The only unusual thing about the bowl is that three ancient Hebrew letters (the kind used before the Babylonian Exile) have been incised on its inside:

Some scholars who had studied the inscription in the past assumed that these letters must have been a proper name denoting ownership of the bowl. However, this name is otherwise unknown.2 To meet this objection, it was suggested by some scholars that the three letters might be an abbreviation of a longer name.

I quickly rejected the idea that the inscription was a name or even an abbreviation of a name. In the first place, ancient Hebrew inscriptions of ownership incised after firing appear, for the most part, on closed vessels (jars, jugs and decanters), not on open vessels like bowls. More important, they are always (at least where the beginning of the inscription is intact) preceded by the preposition

It seemed to me more likely that the inscription was meant as an instruction to put certain commodities into the bowl. By analogy, a group of Iron Age bowls found in Judah and Israel were engraved on the inside with the word

Perhaps, I reasoned, the inscription on the bowl I was studying had a similar function—to indicate what was to be placed in the bowl.

Hebrew is written almost wholly with consonants, so the same letters can often be pronounced in more than one way. It was long ago recognized by some scholars that the three letters

I believe that this inscription was intended to signify that contributions to the poor were to be placed in the bowl. The bowl was probably placed in a cultic location—a temple, shrine or high place. The inscription was an instruction to worshipers to deposit into the bowl commodities that, by Biblical law, they were required to give to their poor brothers. The contents were then distributed by the priests to the needy.

In ancient Israelite society there was a bond of brotherhood between all members, which was sometimes extended to include mankind as a whole. The term

“Brother” was also used in the ancient Near East to denote someone of equal rank or status. It is most commonly used in the Bible as an epithet for a fellow Israelite (Numbers 20:14; 1 Kings 9:13). It also appears in this sense in an inscription on one of the famous Arad ostracab4 and in international correspondence.5 In these sources, “brother” stands in contrast to “father” (’b, av) and “son” (bn, ben), which indicate superior and inferior status respectively.

In the Biblical laws referring to social justice, the poor are called “your brother” (

The crops of the seventh year were to be set aside for the poor (Exodus 23:10–11; cf. Leviticus 25:4–6). Moreover, the tithe of the third year was not to be brought to the Temple, but, instead, was intended for the poor and the less privileged sectors of Israelite society, and could be eaten locally (Deuteronomy 14:28–29, 26:12–13). It is in this context that we must understand the inscription inside the Beth Shemesh bowl.

One objection to the interpretation I am offering is that the bowl was found in a burial cave. But this probably reflects its secondary use as a container for burial gifts. Some bowls inscribed with the word kodesh (

Thus, the inscribed bowl from Beth Shemesh was apparently meant to contain food for the poor, who were called, echoing the Bible, “your brother.”

(For further details, see G. Barkay, “‘Your Poor Brother,’ A Note on an Inscribed Bowl from Beth Shemesh,” Israel Exploration Journal 41 [1991], pp. 239–241.)

MLA Citation

Footnotes

B.C.E. (Before the Common Era), used by this author, is the alternate designation corresponding to B.C. often used in scholarly literature.

Endnotes

See Duncan Mackenzie, “Excavations at Ain Shems (Beth-Shemesh),” Palestine Exploration Fund Annual 2 (1912–1913), pp. 86–88, pl. 54:13; J.H. Iliffe, Palestine Archaeological Museum, Gallery Book, Iron Age (Israelite Period) (Jerusalem, 1940), p. 55, no. 518.

Gabriel Barkay, “A Bowl with the Hebrew Inscription