018

During the Second World War,” the guide was saying, “all these windows were taken out and put in storage. We were afraid of bombs.”

We were standing in St. John’s Church in Gouda, just an hour’s bus ride from Schiphol Airport in Amsterdam. Gouda is the town in the Netherlands famous for its cheese. “Erasmus spent much of his boyhood here in Gouda,” the guide continued. But we had stopped here to see this “tremendous Dutch church with a town around it,” as the guidebook put it, with its remarkable stained-glass windows. I was looking for one window in particular.

The church is “tremendous,” the length of a football field and a quarter, with 70 stained-glass windows, most of them from the late 1500s. The most recent is a window from 1947 depicting the liberation of Holland, with airplanes, a concentration camp and a man making a “V for victory” sign. The largest windows are more than 60 feet high. I was on the edge of the group, half listening, half looking for that window.

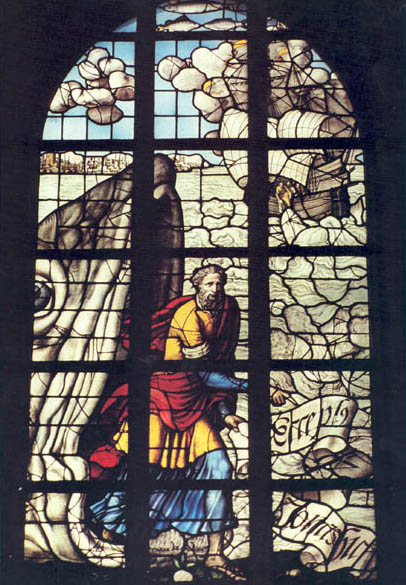

I knew something of the history of this church. In 1552 it had been struck by lightning and almost destroyed. The people of Gouda decided to rebuild it, and asked various individuals and groups to donate windows. A bishop donated a John the Baptist window. The local butchers donated Balaam and the ass. The Crabeth brothers crafted 14 of the windows. Finally, I found what I was looking for. High up in a corner, there it was: the Jonah window (above). There was the prophet, clothed in yellow, red and blue, emerging from the mouth of a huge fish.

For a few minutes I thought about the construction of that window. It 020had been made by Dirck Crabeth, in about 1560, when St. John’s was still a Catholic church. The window was donated by the fishmongers of the town. I imagined a meeting of that organization, four centuries ago. The butchers were donating Balaam and his ass. What should these people do who made their living by fishing? “How about the story of the loaves and fishes?” one might have suggested. But then I imagined another, bolder spirit saying, “No, let’s go for something bigger. Why not Jonah and the whale?”

There it stands. A story, a sermon in itself. In the background are the storm clouds and the ship. Jonah is being thrown overboard and intercepted by the whale. In the foreground is a mighty mouth and part of a huge blue eye. The Prophet is emerging, his body language suggesting determination; his clothing, action. His eyes look at you; there is a glimmer of humor in his expression. His finger points to a banner he is carrying, with a slogan in Latin: “Behold, something greater than Jonah is here,” a quotation from Matthew 12:41, which links Jonah and Jesus. The red, yellow and blue colors get brighter as they pick up the morning sun.

I moved through the church, guidebook in hand, to look at some of the other windows: Jesus in the Temple, John preaching on the banks of the Jordan, Jesus being baptized. Some words from Hypatios, a sixth-century archbishop, came to mind:

“We ordain that the unspeakable and incomprehensible love of God for us men and the sacred patterns set by the saints be celebrated in holy writings since, so far as we are concerned, we take no pleasure at all in sculpture or painting. But we permit the simpler people, as they are less perfect, to learn by way of initiation about such things by sight which is more appropriate to their natural development.”1

I left the church feeling grateful to the citizens of Gouda for wanting these window, to the guild of fishermen for their contribution and creativity and to the Crabeth brothers for their craftsmanship. I was happy to be counted among the “simpler people.”

The Book of Jonah unfolds in five scenes.

1. The Runaway (Jonah 1:1–3). The story begins as Jonah the son of Amittai is called by God to “Go to Nineveh, that great city, and speak out against it; I am aware of how wicked its people are.” Ordinarily when a prophet is told, “Arise, go to X” the story then continues, “And so the prophet arose and went to X” (see 1 kings 17:9–10). But not Jonah. Told to go northeast to Nineveh, he sets out 180 degrees opposite, toward Joppa, to catch a boat to Tarshish (probably Spain). What will happen to a prophet who so blatantly disobeys? And what will happen to wicked Nineveh?

2. The Story (Jonah 1:4–16). The Lord sends a storm, the tale continues and the ship carrying Jonah is in danger of disintegrating. Now we meet the sailors. A midrasha tells that they came from the 70 nations of the world, representing the whole human family.2 In any case, they were not Israelites and would be considered outsiders, pagans, by those hearing the story. What do these sailors do when the storm strikes? First, they pray, “each one to his own god.” Then they act, throwing the cargo overboard to lighten the ship. And where is Jonah, the hero of our story? The captain finds him down in the hold, sound asleep.

The captain (again, an “outsider”) seems a decent and pious sort, too. His first words are not, “Why aren’t you helping?” but “Why aren’t you praying?” He says to Jonah, “Get up and pray to your god for help. Maybe he will feel sorry for us and spare our lives.” The storm gets worse. The sailors cast lots to determine who is responsible for their misfortune. Perhaps there is a criminal on board. The lot falls on Jonah.

Now the sailors come at Jonah with a barrage of questions, like reporters going after a presidential candidate. “Who are you? What are you doing here? Where are you from? What is your work?” Jonah tells them that he is a Hebrew who worships the Lord, the God of Heaven, who made both sea and land. Jonah tells the terrified men that he is running away from the Lord. “Throw me overboard and the storm will end and the sea will clam down,” he says.

But the sailors try to save this fellow’s life. They row all the harder to reach the shore. We have been impressed by their piety. Now we are struck by their concern for Jonah! But they fail because the sea 021grows stormy. Finally, they throw Jonah overboard and the sea becomes calm. The awed sailors offer a sacrifice and promise to serve the God of Israel.

3. The Fish (Jonah 1:17–2:10). The story could have ended there, with Jonah disappearing under the waves. The point might have been, “Don’t disobey the Lord’s call!” But there is more. Jonah has not been forgotten. God sends a great fish to swallow Jonah; for three days and three nights the prophet makes his home in the fish’s belly. From there he offers a prayer to the Lord. Aldous Huxley sketches the scene:

“Seated upon the convex mound

of one vast kidney Jonah prays

and Sings his canticles and hymns.

Making the hollow vault resound

God’s goodness and mysterious ways

Til

the great fish spouts music as he swims.”3

Then the Lord gives the command, the fish spits Jonah up on the beach and there he is, sitting in the sunshine.

4. The City (Jonah 3:1–10). We are right back where we started from. The Lord speaks to Jonah, “Arise, go to Nineveh.…” This time the prophet knows better than to disobey. He “arose and went to Nineveh.” Without great enthusiasm he delivers his message, five words in Hebrew: “In forty days Nineveh will be destroyed.”

This announcement is like a spark which sets of an explosion of Ninevite repentance. From the king to the humblest servants, even the animals, all put on sackcloth and sit in ashes to show that they are sorry for their sins. And God changes his mind and decides, not to punish them. Nineveh will survive!

5. The Question (Jonah 4:1–11). How does Jonah feel about all this? We might expect him to be happy. Then when he would return home and his family (3 Maccabees 6:8) asks him, “How did it go in Nineveh?” he would be overjoyed! What evangelist would not be delighted at the response of the people of Nineveh! But in the actual story Jonah is not happy at all. “Lord, didn’t I say before I left home that this is just what you would do?” he complains. “That’s why I did my best to run away to Tarshish. I knew that you are a loving and merciful God, always patient, always kind, and always ready to change your mind and not punish. Now then, Lord, let me die. I am better off dead than alive” (Jonah 4:2–3).

“If those outsiders from Nineveh get in,” Jonah seems to be saying, “then I want out!”

So Jonah sits outside the city of Nineveh and looks at it, wondering what is going to happen. The heat is unbearable. The Lord causes a plant to grow, giving Jonah some shade. He is delighted! But then the Lord commands a worm to attack the plant and it dies, and Jonah tells God that he is “so deeply grieved about the plant” that he wants to die.

Jonah is still angry when the Lord asks him a question:

“You cared about the plant, which you did not work for and which you did not grow, which appeared overnight and perished overnight. And should not I care about Nineveh, that great City, in which there are more than a hundred and twenty thousand persons who do not yet know their right hand from their left, and many cattle as well?”

(Jonah 4:10–11)

The story ends with this question. The focus is on Nineveh, that great—and wicked—city. The message is that God cares for those people, loves them. The word for insiders is that God cares for the outsiders, for the people of the world, even for the cattle! It is not far from what Jesus said, “For God so loved the world …” (John 3:16).

Jonah, as everybody knows, is a story about a prophet and about a “great fish,” which, by Matthew’s time, had been transformed in the popular imagination into a whale (Matthew 12:40). Scholars may point out that the great fish occupies only a very small part of the story (three verses) and that the important message of the book should not be “tied to the tale of a whale.” In the Good News Bible, for example, a series of 21 sketches traces the course of the story—but there is no picture of the whale! Such a huge creature, however, cannot be so easily dismissed from this prophetic book.

Artists have enjoyed the whale. Jonah has called forth an astonishing number of representations in sculpture, painting and stained glass.

The Cranbrook Academy of Art, in Bloomfield Hills, Michigan, displays a bronze Jonah fountain created by Carl Milles in 1932. A playful whale and a jolly Jonah remind us of the humor in the story.4

022

The stained-glass window at Lincoln College Chapel, Oxford, England, tells the whole story of Jonah. It was executed by the Van Linge brothers in the 17th century. We see the storm, the shipwreck and, finally, the prophet emerging, his hand over his heart and his eyes toward heaven. But the whale dominates the window, sporting through the sea and then spewing forth his human cargo.

Three marble pieces, now in the Cleveland Museum of Art, outline the story of Jonah and add a new dimension to it. All three sculptures were found in Asia Minor and date to the third century A.D. In the first, the whale is a serpentine creature, the prophet disappearing head first into its mouth. In the second, Jonah makes a triumphant exit (see

The linking of the Jonah story with hope for resurrection comes from the New Testament. Jesus said, “For as Jonah was three days and three nights in the belly of the whale, so will the Son of man be three days and three nights in the heart of the earth” (Matthew 12:40). Jonah’s experience of being swallowed and then delivered is understood as a preview of the death and resurrection of Jesus. One example of this interpretation is found in the Bible windows in the cathedral at Cologne, West Germany.

To interject a personal note: I visited the Cologne Cathedral on a hot summer day in July. Outside, a brass band was playing, a young Italian was demonstrating his skill on a skateboard and an artist was doing a chalk drawing of Mary and the baby Jesus on the sidewalk. I approached the cathedral looking first for the Jonah-and-the-whale door handle. There it was: a circular door pull (see photo of bronze door pull), again a playful Jonah, partially swallowed, perpetually escaping from the jaws of the whale. Inside, the organ was playing and groups of tourists were gathered, with guides talking about the cathedral in a variety of languages.

Then I found the Bible windows, a series of 023stained-glass panels juxtaposing scenes from the Old Testament with those from the New. There is the Queen of Sheba bringing gifts to Solomon next to the three kings bringing gifts to the Christ child; the serpent that Moses put up in the wilderness is next to Christ on the cross. Jonah is emerging from the whale, hands outstretched (above). Next to him is Jesus emerging from the tomb (below). The interpretation of the Jonah story is clear: The story of Jonah is a preview of the story of Christ.

Juxtaposing Jonah and the risen Christ is a common theme among artists. For the contemporary German artist Robert Eberwein, for example, Jonah and Christ become one: In his “Jona als auferstehender Christus” (Jonah as the Risen Christ), it is Christ who is portrayed as emerging from the fish.

Michelangelo’s work in the Sistine Chapel has been discussed in a past issue of Bible Review.b Before he began his work on the ceiling, the walls contained a series of scenes by other artists juxtaposing events from the life of Moses with scenes from the life of Christ (the circumcision of Moses/baptism of Christ, Moses and the covenant/Christ and the Last Supper, etc.). Thus, there was some sophisticated interpretation of biblical texts going on in the chapel before Michelangelo began his work there.

Michelangelo’s Jonah is front and center, just above the famous “Last Judgment,” directly opposite the entrance to the chapel (see photos of Michelangelo’s Sistine Chapel, below). The image of Jonah is huge, some 9 feet high. The prophet looks upward, his left arm thrown across his twisted body, which appears to recoil from something Jonah sees. In the background lurks the massive head of the great fish.

How are we to understand the Jonah painting in the Sistine Chapel? Michelangelo painted the great figure of Jonah as part of the ceiling composition that portrays events and people in the Old Testament. Jonah connects the ceiling to the western wall above the altar by extending down onto the upper portion of that wall. When Michelangelo returned to paint the “Last Judgment” 25 years after completing the ceiling, Jonah became the link in a chain of compositional relationships extending up from the mouth of Hell, through the upflung arm of Jesus.

Michelangelo painted the ceiling during the Renaissance, from 1508–1512. In those years, there was a new Sense of the past, of the classical heritage from Greece and Rome, as well as a new fascination with the whole world of the present. This was the age of exploration—the age of Columbus and Magellan. Michelangelo’s awareness of history and of the ecumenism of his time is reflected in the subjects he chose to paint on the Sistine Chapel.

The central spine of the chapel’s ceiling is a series of scenes from Genesis, from the creation to Noah. Along the sides of the ceiling are the prophets Jeremiah, Ezekiel, Joel, Zechariah, Isaiah and Daniel. 024Alternating with these prophets are five sibyls, priestesses from the classical world, searching through their sacred books. In a somewhat remarkable affirmation of this non-Hebrew tradition, the artist seems to be saying: God’s revelation came through the Hebrew prophets but through these gentiles, too!

Front and center in the chapel is Jonah and the whale. Why should Jonah occupy so important a position? There is something unique about Jonah in the Bible: He is the only prophet called to address a nation other than Israel. Therefore, this most “ecumenical” of the prophets seems quite at home here, in this context of reminders of God the creator of all that exists and in the company of seers from the non-Israelite world as well as the Hebrew prophets. The God of Jonah, this painting seems to say, is the God who raised Jesus from the dead and also the God who created the heavens and the earth and who spoke through the prophets and through the sacred 025writings of the gentiles.

Finally, let us consider a few works that place particular focus on the prophet’s mission to Nineveh. A mural on the wall of Siegfried’s Mechanishces Musikkabinett in Ruedesheim, Germany, not far from Mainz, tells the story of Jonah with familiar scenes. Of special interest is the fact that the skyline of the city of Nineveh in the background is really the skyline of Mainz! This interpretation says: “Nineveh” is the city nearby that needs to hear the prophetic word!

Exceptionally beautiful is the Jonah window in Christ Church Cathedral, Oxford, England. This—like the window of Lincoln College in Oxford—was crafted by the Van Linge brothers of Emden, Ostfriesland, in 1631. The scene is from the end of the story. Jonah is sitting under the gourd tree. But his focus—and ours—is on the city of Nineveh. We see the houses, the shops, the streets; we cannot help recalling the words of the Lord at the end of the story, “But should I not pity Nineveh, that great city. …”

The Jewish artist Marc Chagall did a series of six sketches illustrating the Jonah story (see photos of sketches by Marc Chagall in the next article). One shows the ship in the storm, Jonah going down into the depths. Another pictures Jonah inside the fish, appearing to enjoy the ride in comfort. Yet another has the fish spewing Jonah out. But the series does not end with Jonah’s escape or with his lounging under a tree. The final sketch shows the prophet, staff in hand, setting out on the way to Nineveh. Is that God smiling above?

The last book written by the great Old Testament professor Gerhard von Rad was a study of Abraham. Included in the book are reproductions of four works by Rembrandt, with this statement about the artist:

“With his incomparable eye he roamed through the narratives of the Bible as through very familiar territory. But as he illustrated these scenes, he always came up with something entirely new.”5

The Heidelberg theologian discovered something new in the Bible because of those illustrations (see photo of Rembrandt sketch of Jonah in the next article).

The Bible has never been the exclusive property of rabbis and, theologians, scholars and priests, professors and preachers. Others have roamed through its territory: poets and playwrights, sculptors and singers, artists and artisans. Could we not learn about Jonah, as von Rad did about Abraham, by asking what artists have found in their explorations of the Bible?

The Bible has always been the book of all the people. Think of the contribution of the fishermen of Galilee—and also of those fishmongers in Gouda.

During the Second World War,” the guide was saying, “all these windows were taken out and put in storage. We were afraid of bombs.”

You have already read your free article for this month. Please join the BAS Library or become an All Access member of BAS to gain full access to this article and so much more.

Already a library member? Log in here.

Institution user? Log in with your IP address or Username

Footnotes

See Jane and John Dillenberger, “Michelangelo’s Sistine Ceiling—To Clean or Not to Clean,” and Suzanne F. Singer, “Understanding the Sistine Chapel and Its Paintings,” BR 04:04.

Endnotes

Pirkei d’Rabbi Eliezer; see Jonah; A New Translation with a Commentary Anthologized from Talmudic, Midrashic and Rabbinic Sources, translation and commentary by Rabbi Meir Zlotowitz (Brooklyn: Mesorah Publication, 1978), p. 88.

Aldous Huxley, “Jonah,” in The Cherry Tree, ed. Geoffrey Grigson (New York: Vanguard, 1959), p. 211.

I found this fountain thanks to a tip from Prof. Palmer Eide of Augustana College, Sioux Falls, South Dakota.