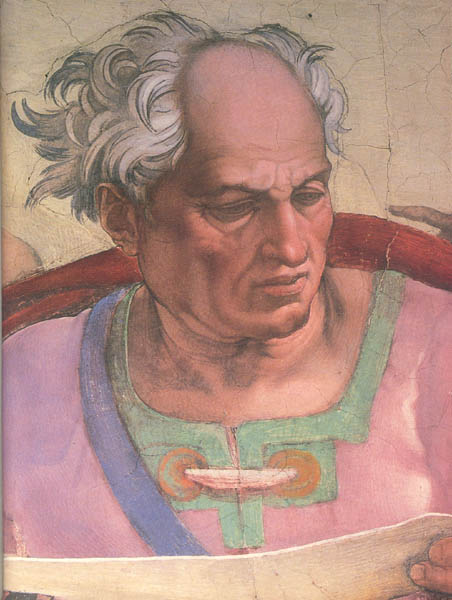

The prophet Joel recently emerged in brilliant color on the freshly cleaned ceiling of the Sistine Chapel—with honey-colored tunic, scarlet scarf and mint-green cloak lined with pomegranate billowing about his knees.a Artists and art historians reacted with disbelief. They proclaimed these glowing colors in unusual combinations “un-Michelangelesque.” For years they had been saying that Michelangelo painted in subdued tones, as if he were representing sculptures, rather than using flesh hues and intense local colors.

A storm of criticism of the Sistine ceiling’s cleaning has rumbled out of the art world. The critics contend that the cleaning process is actually destroying Michelangelo, leaving us with only the beginning stages of what he was doing, having removed his own corrections and modulations. They warn that what we now see may be subject to further deterioration, because of the continuing action of the cleaning compound.

Every art historian concerned with the condition of the Sistine ceiling immediately thinks about Leonardo da Vinci’s “Last Supper,” a haunting example of the extent to which unchecked deterioration can leave only a ghost of the original creation. The differences between the “Last Supper” and the Sistine Chapel ceiling, however, are considerable. In the former, deterioration was evident early, for Leonardob did not use a true fresco process, and the oil and varnish in the paint began to cause paint losses on the damp wall even in his lifetime. Already in 1517 it was reported that the work had begun to perish. By contrast, the Sistine Chapel, except for limited areas of irreversible water damage, still has the full Michelangelo lying under the accumulations of soot and smoke and the additions of later restorers.

The critics charge that what time has done with Leonardo’s “Last Supper,” the restorers may be doing now to Michelangelo’s Sistine ceiling.

Who are the critics and what, more specifically, are they saying? While there is limited criticism in Italy, and practically none in the rest of Europe, extensive criticism calling for a halt to the restoration has resounded from the United States. Professor James Beck, head of Columbia University’s department of art history, and Alexander Eliot, a former editor of Time magazine, represent the major U.S. critics. While Beck first approved the project, he changed his mind on a second visit to see the ceiling, maintaining in an interview in People Weekly (March 30, 1987) that the “bright new colors are incorrect. They were made to have a filtered layer. That layering, I maintain, has been removed.” Believing that Michelangelo’s work was being destroyed by the removal of the layers that made it unique, it is understandable that in an open letter in the Roman daily La Repubblica Beck accused Gianluigi Colalucci, head of restorations at the Vatican Museums, of “indiscriminate removal of ‘secco’ passages [painting on dry plaster] and veils of tone applied by Michelangelo himself.” Beck asked rhetorically, “Will you go down as the man who destroyed the subtlety of Michelangelo’s ceiling?”

Alexander Eliot added his voice to the protest in the influential Harvard Magazine (“The Sistine Cleanup: Agony or Ecstasy?” March-April 1987). While not a professional art historian or restorer, Eliot felt that he knew the ceiling as few others did, having spent over 500 hours in 1967 on a specially constructed aluminum moving tower, examining the ceiling in connection with the ABC television documentary, “The Secret of Michelangelo, Every Man’s Dream.”

Two of Eliot’s points sound reasonable enough: (1) nothing like unanimity about how to clean the frescoes exists among conservators and (2) the procedure is irreversible. Once cleaned, Eliot states, the real Michelangelo Sistine ceiling will be no more. Eliot refers to the earlier restorations of the 15th-century frescoes on the sidewalls of the chapel, which were cleaned in the 1960s, and Michelangelo’s lunettes over the windows on the super side walls, which were the first work to be cleaned in the 1980s restoration program. Eliot notes the unacceptable flatness that resulted from both earlier cleanings and he warns that these losses were of lesser magnitude than the loss confronting us by cleaning the Sistine ceiling.

Moreover, Eliot is not convinced that cleaning is necessary. While on the scaffolding in 1967, he observed that the colors of the ceiling were clear and that the floor below, not the ceiling had a “grayish-brown sheen.” Eliot concluded that a layer of “dust and biological pollution” lay suspended between the floor and the ceiling, giving the viewer standing below a false impression that the ceiling itself was dark and grimy.

Eliot’s central criticism, however, like that of Beck, is that Michelangelo’s corrections and balancing of colorations are being removed, leaving only incomplete or early stages of the project. For that reason, Beck said that “we might after all listen to the warnings of the painters who think with their eyes.”

Both Beck and Eliot contend that Pope Julius 2, Michelangelo’s patron, was impatient to see the ceiling completed even though Michelangelo was not satisfied that he had made the final adjustments in tonality. Beck quotes Ascanio Condivi, an early biographer of Michelangelo, who observed that the Pope was impatient “even though it [the ceiling] was imperfect not having had the final layer.” “So,” adds Beck, “what was the ‘final layer,’ if not the glue, size, oil, varnish, touchups or whatever, most of which is being speedily wiped away?” Or to quote Eliot, “Doesn’t it seem more reasonable to conclude that the master kept on deepening, purifying, harmonizing, and spiritualizing his work a secco, while Julius fumed? What the cleaning does,” Eliot claims, “is expose the flattish, schematic, and deliberately bright-colored underpainting, the water-based foundation sketches with which Michelangelo began.”

Given such criticisms, it was natural that 14 leading U.S. artists—including Robert Motherwell, George Segal, Susan Rothenberg and the late Andy Warhol—added their voices to the protest with a petition to Pope John Paul 2, on March 14, 1987, requesting that he halt the restoration until questions could be resolved.

The Vatican naturally felt challenged by the attacks emanating from the United States, though not at all convinced that its restorers were on the wrong track. It nevertheless welcomed a full exploration of every facet of the project: The American-based Kress Foundationc on April 16, 1987, brought an international group of leading conservators of Italian paintings to the Vatican to examine every aspect of the project. Their conclusions vindicated the Vatican’s restoration program, leading Motherwell, one of the protesting artists, to place more confidence in the results of the restoration, although still wondering whether conservators, like artists, do not have a tendency to stick together. But a wide range of art historians who have examined every facet of the work agree with the restorers.

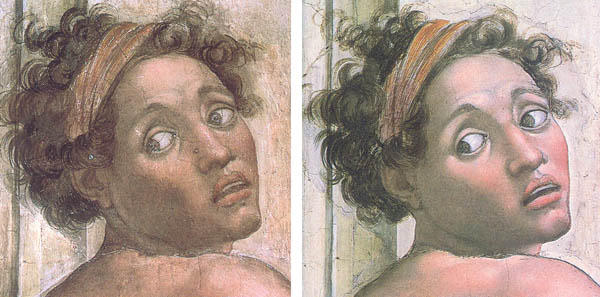

There are answers to Eliot’s charges, all of which have been succinctly brought together by M. Kirby Talley, Jr., in an article entitled “Michelangelo Rediscovered,” published in the Summer 1987 Art News. The Vatican itself admits that some of the photographs, taken shortly after the cleaning began in 1980 and used as the basis of much of the criticism, were shot with too much focused, artificial light. The result was the flat appearance of the cleaned area. Now the artificial lights have been turned off the cleaned part, and the painting has none of the flatness found in the first photographs. The flood lights now focus only on the uncleaned part.

Furthermore, spotlit photographs distort the uncleaned parts by penetrating the dirt and giving a clearer, more colorful version than the human eye can see.

Having read the criticism of the restoration and having talked with artist and art historian friends who were against the cleaning, we decided to learn and to see for ourselves while in Rome in July 1987. Our host and guide who shared with us his viewpoint, as well as the technical details of the restoration, was Dr. Walter Persegati, head of the Vatican Museums.

Persegati expressed surprise and sadness about the controversy, saying that he and his associates are convinced they are not only revealing the original colors and draughtsmanship, but that they are saving the ceiling from eventual destruction. Large areas in which the weight of encrustations upon the paint surface has caused the surface to break away from its ground are being resecured to the ground, thus preventing the eventual loss of these areas.

The Vatican’s cleaning compound, developed in Italy in the 1960s and widely used since then without adverse effects, has been hailed as the best in the trade. The cleaning compound, consisting of ammonium bicarbonate, sodium bicarbonate, and carboxylmethylcellulose diluted to a paste in distilled water, is applied for no more than three minutes to a square foot of the original fresco after first dusting and washing the area with distilled water. (Water alone is not sufficient, because it does not penetrate the encrustations.) Then the compound and dirt are removed with distilled water and sponges. After 24 hours, the process is repeated. If further cleaning is necessary, it is done only in the exact sports requiring cleaning.

To clean the a secco additions, another compound, known as AB-57, is used. With both compounds the restores must judge the extent of penetration of the fresco surface so that the compound will be thoroughly removed by distilled water and will not continue to penetrate the frescoes and cause later damage.

We learned from Dr. Persegati that the Vatican is installing an air system that will protect the cleaned ceiling by making sure that no contamination, human or other, reaches it. The system provides a warm cushion of air just below the frescoes that will be a barrier to keep the chapel’s slightly cooler air containing dirt and dust away from the paintings. This cooler air will circulate throughout the chapel, but just below the warmer cushion of air.

Vatican records contain the evidence, Dr. Persegati pointed out, that attempts to clean the frescoes began in the 1540s, in Michelangelo’s own lifetime, with an application of hot animal glue to the painted surface. The glue eventually darkened and sealed in the layers of soot that had accumulated after the ceiling was completed in 1512. In 1625, Simone Lago again cleaned and restored the ceiling, followed, undoubtedly, by a layer of glue varnish. In the 18th century, according to Persegati, overlays of paint were added in order to emphasize contours of the figures that had been obscured by layers of accumulated grime.

Persegati was certain that the cleaned frescoes appear to us today as they would have appeared to Michelangelo and his contemporaries during the brief 30-year period before well-meaning but damaging cleaning attempts began their transformation.

After this introduction, we were eager to see Michelangelo’s masterpiece with our own eyes. We took the somewhat shakey ride in the small cage elevator that connects the floor of the chapel with the scaffolding bridge about 55 feet above. At the time of our visit, July 11, the scaffolding bridge was positioned directly below the blackened fresco of the “Creation of Eve” with the cleaned and radiant “Temptation and Expulsion” partially over the bridge.

From the scaffolding we were privileged not only to assess the restoration efforts, but to experience Michelangelo’s extraordinary paintings as if standing by the master’s shoulder as he worked.

The restorers were completing their final work on one corner of the “Temptation and Expulsion” its glowing color, with each of Michelangelo’s brush strokes visible and vibrant, contrasted startlingly with the “Creation of Eve” fresco. Eve’s Creation was covered with a layer of accumulated dirt, candle wax, glue and the work of earlier restorers who tried to accentuate the forms by adding heavy contour and shadow lines.

Directly in front of us on the bridge were the feet of Adam and Eve, their bodies arching away from us, Michelangelo’s spring-taut line defines the contours of thigh and hip, shoulder and breast. His incisive hatchings create a living shadow along the side of the tree of the knowledge of good and evil, and model the thick tubular form of the female serpent’s long, corkscrew-like tail. Farther out along the ceiling, part of the hair of the seraphim was clearly added at another time; the paint seemed to lie upon the surface rather than being absorbed into the surface of the ceiling. The restorer explained that Michelangelo, not another later hand, did this after the giornata of this area. The term—meaning, “a day’s work”—is used for the area completed in one day, that is, the area covered with fresh plaster on which Michelangelo painted while it remained damp and receptive to the paint. The later paint would have been added a secco, that is, over the dry surface of the ceiling.

Directly above us, the majestic, erect figure of God gestured to the plump and prayerful figure of Eve to arise from the side of the sleeping Adam. Last July, this entire panel was still blackened by heavy layers of swarthy soot. It was the next to be cleaned and, when we saw it, minute numbers in white paint were distributed in clusters about the surface, indicating places where microscopic samples of the grime of centuries were taken to perform analyses, a kind of biopsy, in preparation for cleaning.

Looking from the bridge across the ceiling toward the “Last Judgement” on the wall above the altar at the western end of the ceiling, we saw at eye level the familiar “Creation of Adam,” awesome when so near at hand. The langorous Adam from this view seemed impossibly long of thigh and limb. His face, which was about two feet from the bridge, had a whitish encrustation about the eyes and bridge of the nose. Great black cracks run vagrantly across the sky between him. and his Creator. The electric hiatus between their two fingers is smaller than one would expect from viewing the scene from the floor 60 feet below: it is only one-half to three-quarters of an inch. The scenes running down the central axis of the ceiling of God Creating the Sun and Moon, God’s Spirit Moving Over the Waters, God Separating the light and the Darkness—all still assert their power through clearly visible layers of soot and dust. Then, confronting us at eye level, was one of the most confounding figures of all, the monumental Jonah, who lunges forward and to the side, the “great fish” encircling his body. He is the Prophet, symbolizing the Resurrection, who looks upward toward his Creator and the heavens.

Turning from Jonah over the chapel’s altar to the prophet Joel above the entrance at the opposite end of the chapel was to turn from murky evenfall to joyous morning light. The freshly cleaned Joel is robed in brilliant green, red, bittersweet honey colors; Jonah is monochromatic.

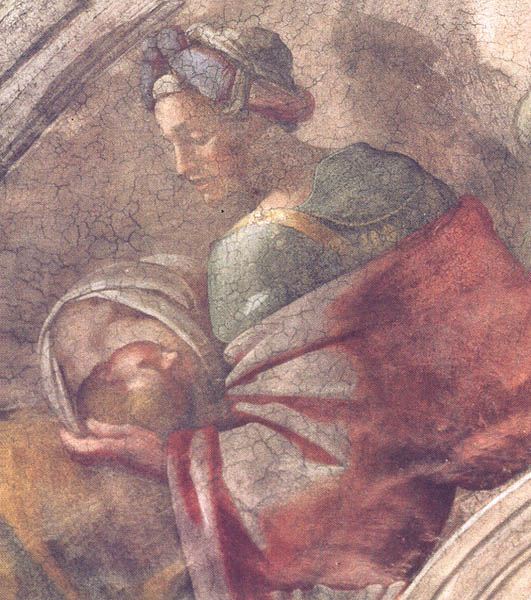

From the bridge, we saw how Michelangelo changed proportions of the human figures so that when viewed from the chapel floor they would not seem distorted. The figures of the prophets Ezekiel and Zecharias and the ignudi or seated male nudes are painted with massive shoulders, arms and legs, while their lower torsos and upper thighs are truncated.

The cleaning of the Sistine Chapel ceiling is not only giving us the colors and tonality of Michelangelo’s original frescoes, but is, in fact, preserving them from imminent paint losses. The computer used by the technicians to record their findings at each stage of their work shows, for example, the “Temptation and Fall” in outline and maps on it large areas where the surface of the fresco has begun to pull away from its ground: when this happens, air gets between the painting and its ground, eventually loosening the surface which can then fall. By identifying these problem areas, the restorers are able to intervene before irreversible damage occurs. Indeed, the technical records being kept (including a filming of the whole process) will make it possible in the future, should further restorations be necessary, to know exactly what was done in the 1980s. Such records have never before been kept so diligently.

The cleaning of the ceiling, begun in 1980, had been scheduled for completion by 1988. However, in a conversation on May 9, 1988, Walter Persegati said that the work has proceeded more slowly than expected because each new phase must be preceeded by studies made of paint samples in the laboratories. Now they do not expect to finish the ceiling until 1990. Then the restoration of the Last Judgment will begin, probably taking two years or less. Access to the Last Judgment, on its vertical wall, will be easier than access to the high horizontal surface; of the ceiling frescos.

For years we have known the great scenes of Creation, the Prophets and Sibyls, the Ancestors of Christ enshrouded by a dark layer of grime. Books reproduced the blackened paintings, and young art historians were trained by seasoned scholars using slides of these darkened, penumbrous frescoes. Scholars wrote learned books and papers about the ceiling using illustrations which—we know now—falsified Michelangelo’s original work.

Art historians have said in the past that Michelangelo was a great draughtsman but not a great colorist. The restoration will forever change that view. Gone is the certainty that a dark opaqueness, equated with mystery, is the real Michelangelo. Instead we have a Renaissance Michelangelo, with clarity and brilliance of color. Moreover, there is corroboration that Michelangelo used such color in another painting by the master, executed some two years before the artist began the Sistine ceiling. In the “Doni Madonna” in the Uffizi in Florence—an oil painting, not a fresco—the range of colors used is consonant with the fresco colors as we now see them in the cleaned ceiling areas—robin’s egg blue, pink, orange, peach, fern green.

Not only must we revise our understanding of Michelangelo’s use of color, but we must also—as a result of the restoration—revise our views about how he worked on the ceiling and wall surfaces.

Earlier artists who painted frescoes generally did considerable later revisions and adjustments in tonality. The usual practice was to revise a secco, that is, by overpainting upon the already dry stucco surface. Michelangelo did that, too, but what is startling is how little he did and how readily it can been seen by the human eye.

Apparently Michelangelo did most of his reworking with the wet stucco. How this was done has been described by Andrea Rothe, conservator of the J. Paul Getty Museum. Speaking for the group of conservators who studied the restoration for the Kress Foundation, Rothe observed that Michelangelo exceeded the normal span of 10 hours for working with wet stucco. “The wall itself remains wet for longer than ten hours,” Rothe commented, “and thus pigment mixed with calcium hydroxide can be applied thinly in such a way that it still bonds.” Hence, Michelangelo put on semi-transparent layers of color that created a shot-silk effect that he could rework for days afterward. It is, therefore, clear why Michelangelo executed so few a secco additions. Those that he did are quite easy to see—even for a novice—when pointed to with a raking light, or even by human touch; the paint added to the dry plaster is slightly raised above the level of the original wet painted paster. That such a secco additions are being removed, Rothe asserts, is simply not true.

After seeing the restoration of Michelangelo’s monumental fresco, as close as he himself saw it as he worked, and after speaking to the restorers about their task, we are no longer dubious about the value of cleaning these beloved paintings. We rejoice that Michelangelo has been restored to us, as he was known to his contemporaries: a great colorist painter and sculptor.

MLA Citation

Footnotes

Before reading this article, turn to “Understanding the Sistine Chapel and Its Paintings.” The plan of the Sistine Chapel ceiling and the photographs in the article will be especially useful for understanding details in the larger context of the Chapel and its complete ceiling.

Leonardo’s work was commissioned by Ludonico il Moro for the refectory of the Convent of Dominican friars at Santa Maria delle Grazie, Milan. The “Last Supper” was probably begun in 1495 and finished by 1498.

The Kress Foundation collected, researched and cleaned a very large body of medieval, Renaissance and baroque old masters’ paintings, and then dispersed them in groups to museums all over this country. The Foundation research and dispersal center was the National Gallery of Art in Washington D.C., which still owns the largest and finest group of Italian paintings from the Kress Collection.