046

The ossuary (bone box) inscribed, “James, son of Joseph, brother of Jesus,” has become famous all over the world.a There is another group of now nearly forgotten bone boxes, however, that are also very likely connected to Jesus. They very probably belonged to the family of Simon of Cyrene, the man who carried the cross of Jesus on the way to the Crucifixion (Matthew 27:32; Mark 15:21; Luke 23:26). Though these ossuaries may not be as important as the “James, brother of Jesus” bone box, they do illuminate the world of Jesus—first-century C.E. Jerusalem—and, more strikingly, add one other figure from the New Testament to the list of Biblical characters attested by archaeology and history.b

Ossuaries were widely used in Jerusalem in the first century C.E. When someone died, his or her body would be laid on a stone ledge inside a burial cave (after his crucifixion Jesus would likely have been placed on such a ledge in a cave tomb) or in a long niche in the cave wall. A year later, after the flesh had fallen away, family members would gather the bones into an ossuary; some ossuaries contained the bones of several family members. Ossuaries are typically made of stone and measure about 2 feet long—a little longer than a thigh bone, the longest bone in the body—and a foot-and-a-half wide and high. Some ossuaries are elaborately decorated (at least on their front faces), but most are plain or even rough. The names of the deceased 048are sometimes crudely scratched on the side or back.

Why are the Simon family bone boxes so little known today? Sometimes important artifacts are destined to be buried twice: first by the debris of history and again, after having come to light, by a lack of public exposure and a fall back into obscurity. That was the fate of the Simon family ossuaries—until now.

The modern-day history of the Simon family ossuaries begins in 1941, when Palestine was ruled under the British Mandate. Hebrew University professor Eleazer Sukenik and his assistant, Nahman Avigad, investigated an ancient tomb in the Kidron Valley, east of the ridge on which the Old City of Jerusalem rests and south of the Arab village of Silwan. Sukenik would later become famous for acquiring the first Dead Sea Scrolls for the State of Israel; he was also the father of famed archaeologist Yigael Yadin. Avigad would go on to have a major career in his own right as an archaeologist and epigrapher (a specialist in ancient inscriptions), a career capped by his excavation of the Jewish Quarter of the Old City of Jerusalem from 1969 to 1983.

The Kidron Valley tomb was not, as is so often the case today, discovered during a construction or road project but was instead located by Sukenik and Avigad in a systematic archaeological survey. The tomb proved to be a single-chamber, rock-hewn burial cave; the entrance was blocked, though not tightly sealed, by a partly broken closing stone.

Sukenik and Avigad documented their finds, carefully cleared the tomb of its contents, and catalogued and stored the artifacts. But, with the exception of some brief notices by Sukenik in scholarly journals,1 complete information on the discovery was not made available for decades. By the time Avigad published an article on the tomb in 1962 (Sukenik had died in 1953), the finds lacked the immediacy of a recent discovery.2 049The tomb and its contents slipped into obscurity, garnering little notice for the past four decades.

The tomb chamber consisted simply of a standing pit hewn into the floor; the digging of the pit formed a continuous shelf along the side and back walls. Interestingly, such an arrangement is often associated with the First Temple period (tenth–sixth centuries B.C.E.). During the late Second Temple period (first century B.C.E.–first century C.E.), more than half of the burial caves around Jerusalem featured finger-like niches cut several feet into the chamber wall; these niches are called kokhim in Hebrew and loculi in Latin. A second, less common, type of burial cave (about one tomb in eight) consisted of wide, shallow arched niches cut into the cave wall, creating a shelf ledge; these are called arcosolia in Latin.

Despite this tomb’s design, the pottery found inside left no doubt about when it was last used. Sukenik and Avigad found 13 intact vessels, including a Herodian oil lamp (considered especially useful for dating). The pottery put the date of the cave’s last use in the first century C.E.

Of greater interest were 11 ossuaries found together on the left side of the cave. Opposite them were scattered, decayed bones, evidence of one or more primary burials left lying to decay on the stone bench. It is easy to imagine the family that owned the tomb placing the body of a close relative in the burial cave just before they were killed themselves or forced into exile by the Romans in 70 C.E. without being allowed to return to the tomb to gather the bones in an ossuary. The published reports by Sukenik and Avigad do not mention what became of these bones (or of the bones that would have been in the ossuaries, which were undisturbed) after the archaeologists found them; presumably the bones were re-interred elsewhere, in accordance with Jewish law and custom.

All 11 ossuaries were plain, undecorated chests, but nine of them—an unusually high proportion—bore an inscription (and some had more than one). Ossuary inscriptions were rarely carved by a skilled professional engraver; they were usually crudely rendered, probably by a relative. Their main function was to identify to family members the remains contained in the various chests. Inscriptions are therefore written in chalk or charcoal or simply scratched with a nail into the soft limestone surface. With one exception, the inscriptions on these Kidron Valley ossuaries are as crude as any.

Sukenik and Avigad found 12 names in 15 inscriptions on the ossuaries and lids, all in Greek letters except for one in Hebrew and one bilingual inscription—in Greek and Hebrew. Four of the names are typically Jewish: Sara, Sabatis (the feminine form of Shabbatai), Jacob and Simon; the first three had not previously been found on ossuaries and were names used chiefly in the Diaspora. And of the eight Greek-style names, most were not known among Greco-Jewish inscriptions in Palestine, but some were especially common in Cyrenaica, in North Africa. The inscriptions thus suggested that the family entombed in the cave came from a Jewish Diaspora community, most likely from Cyrenaica.

Cyrenaica lay in the eastern part of modern Libya. Cyrene, its chief city during the Roman period, sat on a plateau inland from the Mediterranean, 500 miles west of Alexandria and 700 miles east of Carthage, as the crow flies.

Cyrene was founded as a Greek colony in about 630 B.C.E. It later came under the rule of Alexander the Great and then of his successor dynasty, the Ptolemies of Egypt. By the first century B.C.E., Cyrene was the capital of a Roman province. Excavations at the site in the early 20th century, mainly by Italian teams, uncovered extensive remains, including a temple to Apollo, the agora-forum, the theater and a vast burial ground.

The Jewish community in Cyrene dates to about 300 B.C.E., when Jews came as settlers from Egypt. Jews from Cyrene, like their counterparts from other Diaspora communities, visited Jerusalem during the three great pilgrimage festivals (Passover, Pentecost and Tabernacles), and it is clear that some of them settled there as well. The Book of Acts, when describing the descent of the Holy Spirit during Pentecost, says, “There were devout Jews from every nation under heaven living in Jerusalem…Phrygia and Pamphylia, Egypt and other parts of Libya belonging to Cyrene, and other visitors from Rome, both Jews and proselytes” (Acts 2:5, 10). According to Acts 6:9, some Jews from Cyrene quarreled with Stephen, who was to become the first Christian martyr; this suggests that the Cyrenians either had their own synagogue in Jerusalem or formed an identifiable group within a larger synagogue. Cyrenians were also a part of the earliest Christian communities 050in Jerusalem (Acts 11:19–20) and Antioch (Acts 13:1).

Two of the Kidron Valley ossuaries found by Sukenik and Avigad bear the name Simon. One reads “Sara (daughter) of Simon, of Ptolemais.” The city is not likely to have been Ptolemais-Acre (modern Akko, just north of Haifa); given the family’s apparent Diaspora origins, a better candidate would be the Ptolemais in Egypt or, better yet, the Ptolemais located west of Cyrene, in the region of Cyrenaica.

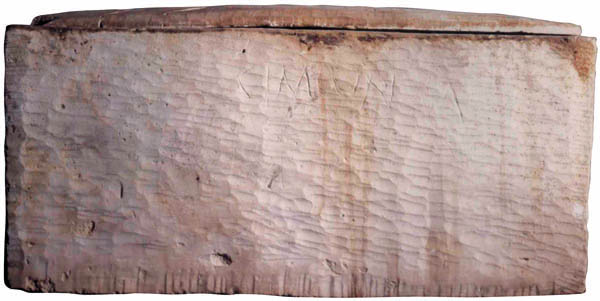

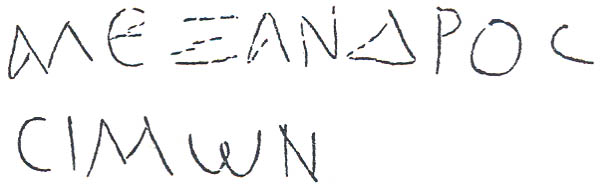

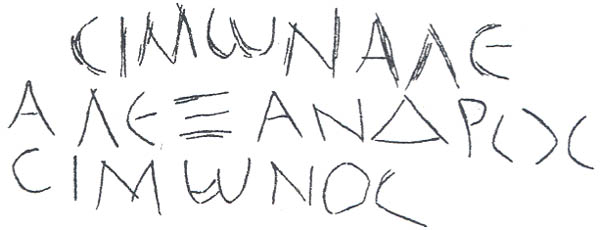

The second Simon ossuary—the one that’s of main interest here—is inscribed in three places. The front bears a two-line inscription, possibly written in green chalk, that reads, “Alexander (son) of Simon.” Each name appears on its own line. The back of the ossuary contains a sloppily executed three-line inscription, the first line of which is clearly an error. It reads, “SimonAle.” Realizing his mistake, the engraver started over again, writing “Alexander” on the second line and “(son) of Simon” on the third.

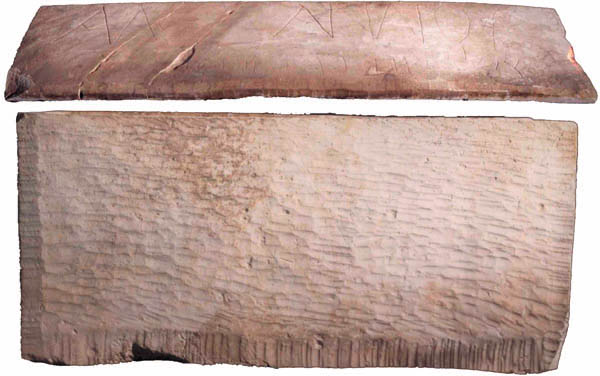

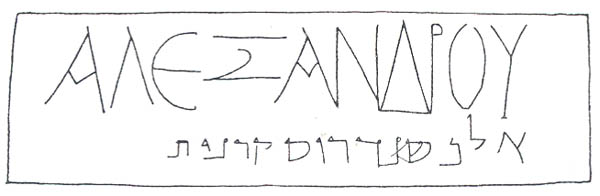

The third inscription on this ossuary is perhaps the most interesting. It is written on two lines across the lid; it is the most neatly incised inscription of all the inscriptions in the burial cave. The top line, in Greek, reads, “of Alexander.” The second line, in Hebrew, says, “Alexander QRNYT.” What does this last term mean? Avigad suggested two possibilities. It may be a word related to aromatic leaves used for medicinal purposes; in that case, qrnyt might be a nickname that refers to Alexander’s profession (if he was, for example, an apothecary). The second possibility is that the engraver’s hand slipped a bit on the last letter and that he had meant to write qrnyh—Cyrenian. Avigad believed that a slip was unlikely but still felt that the word might somehow be connected to Cyrene; he pursued this possibility but never reached a firm conclusion.

We, of course, know of a first-century C.E. Alexander, son of Simon. In describing the crucifixion of Jesus, the Gospel of Mark writes, “They compelled a passerby, who was coming in from the country, to carry his cross; it was Simon of Cyrene, the father of Alexander and Rufus” (Mark 15:21; Matthew and Luke give similar reports).

Interestingly, the common image of Jesus carrying the cross is a mix of gospel accounts of these incidents. The three Synoptic Gospels (Matthew, Mark and Luke) do not describe Jesus taking up his cross; instead, they say Simon of Cyrene was compelled to carry the cross for Jesus. The Gospel of John, on the other hand, does not mention Simon and says that Jesus “went out bearing his own cross” (John 19:17). The popular conception, then, harmonizes the two gospel strands: Most of us imagine Jesus carrying his cross at first, when, having been scourged and near death, he stumbles under its burden; Simon is then forced by the Romans to carry the cross for Jesus. One other sidelight: From what we know about Roman practice, Jesus (or Simon) would have carried only the horizontal cross-beam of the cross, which would have been affixed to an upright beam at the crucifixion site.

What are the chances that the Simon who is named as the father of the Alexander interred in the Kidron Valley ossuary is the same Simon who carried the cross for Jesus? As with the “James, brother of Jesus” ossuary, we cannot know with certainty whether the inscriptions we have refer to the characters who appear in the New Testament, but we do have some sense of the relative likelihood. In the case of the James ossuary, the frequency of the names James, Joseph and Jesus in first-century C.E. Palestine yielded only some four to 051twenty possibilities over two generations. In our case, Simon was the most common Jewish name in first-century C.E. Palestine (the New Testament alone mentions nine Simons). A recent study by Tal Ilan of Hebrew University, an expert on ancient Jewish names, notes that Simon appears 250 times in ancient Jewish inscriptions and other historic sources.3 Alexander, however, appears only twenty times as a Jewish name.

When we consider how uncommon the name Alexander was, and note that the ossuary inscription lists him in the same relationship to Simon as the New Testament does and recall that the burial cave contains the remains of people from Cyrenaica, the chance that the Simon on the ossuary refers to the Simon of Cyrene mentioned in the Gospels seems very likely.

If the burial cave discovered by Sukenik and Avigad does indeed contain the remains of the son of the man who carried the cross for Jesus, all sorts of questions spring to mind. Where are the remains of Simon of Cyrene himself? They do not seem to have been placed in the cave with his son Alexander or his daughter Sara. And where are the remains of Rufus, brother of Alexander? Was he not buried in Jerusalem? Might he have gone to Rome and been the same Rufus greeted by Paul in Romans 16:13?

We are left with many questions and no definitive answers. All we can say for certain is that the facts fit: More than six decades ago two scholars uncovered a burial cave last used in first-century C.E. Jerusalem. The names on the ossuaries point to a family that originated in Cyrenaica; one inscription bears the name Alexander, a name rare among Jews at the time; he is identified as the son of Simon. The Gospels, too, speak of a man from Cyrene, a Simon, father of Alexander.

I find it very unlikely that there could have been two families living in first-century C.E. Jerusalem, both of them from Cyrene in North Africa, both of them headed by a man named Simon and both of which men gave their sons the uncommon name Alexander. I believe the Simon memorialized on the Kidron Valley ossuary was very likely the Simon of Cyrene who carried Jesus’ cross at the Crucifixion.

Adapted from an article in Artifax (Autumn 2002), a quarterly digest and commentary on developments in Biblical archaeology.

The ossuary (bone box) inscribed, “James, son of Joseph, brother of Jesus,” has become famous all over the world.a There is another group of now nearly forgotten bone boxes, however, that are also very likely connected to Jesus. They very probably belonged to the family of Simon of Cyrene, the man who carried the cross of Jesus on the way to the Crucifixion (Matthew 27:32; Mark 15:21; Luke 23:26). Though these ossuaries may not be as important as the “James, brother of Jesus” bone box, they do illuminate the world of Jesus—first-century C.E. Jerusalem—and, more strikingly, add one other […]

You have already read your free article for this month. Please join the BAS Library or become an All Access member of BAS to gain full access to this article and so much more.

Already a library member? Log in here.

Institution user? Log in with your IP address or Username

Footnotes

See André Lemaire, “Burial Box of James the Brother of Jesus,” BAR 28:06.

See Steven Feldman and Nancy E. Roth, “The Short List: The New Testament Figures Known to History,” BAR 28:06.

Endnotes

Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Religion 88 (1942), p. 38, and Qedem 1 (1942), p. 104 (Hebrew).

Nahman Avigad, “A Depository of Inscribed Ossuaries in the Kidron Valley,” Israel Exploration Journal 12 (1962), pp. 1–12.