Despite the uncertainties and controversies concerning Jesus’ life and death, there is universal agreement about at least one thing: He was crucified. Yet even here questions have been raised, questions about the physical cause of death and about how people were nailed to the cross. I would like to address these two questions, or at least particular aspects of them.

Since the 1920s, it has become common wisdom that victims of crucifixion die of asphyxiation when they lose the ability to raise the chest in order to breathe.

It is also widely assumed that nails in the palms of the hands would not hold the weight of the body on the cross; the flesh would tear and pull off; therefore, the nails must have gone through the wrists in order to obtain an adequately secure hold.

Both of these propositions are incorrect.

The suggestion that crucifixion victims die as a result of asphyxiation was first made by A. A. LeBec in 1925.1 LeBec theorized that the position of the crucified person on the cross, with the arms overhead, would immobilize the chest, making it difficult to breathe out. Thus, the person would suffocate. This was supported by R. W. Hynek in 1936.2 It was, however, Dr. Pierre Barbet, a surgeon from Paris, who gave the theory widespread currency. In 1953 Barbet refined the theory and presented it in a very simple and believable way.3

Barbet used three kinds of evidence to support his asphyxiation hypothesis, the most important of which was evidence from hangings in the Austro-German army during World War I, and in the Nazi concentration camp at Dachau during World War II.

Barbet’s World War I evidence derived from observations of punishments in the Austro-German army.4 Soldiers were strung up by their wrists with their feet barely raised off the ground. After a short time, violent contractions of all of the muscles occurred, causing severe muscle spasms. The tortured individual had extreme difficulty exhaling, and thus asphyxiation and death occurred in about ten minutes. Barbet reinforced this observation by using the World War II testimony of two prisoners from Dachau.5 The prisoners reported that condemned men were hung by their hands with their feet some distance from the ground, requiring them to raise them-selves by their hands in order to exhale. The victim would continuously raise and drop his body until he became exhausted and succumbed to asphyxiation.

Both observations by Barbet would support the crucifixion-asphyxiation hypothesis only if the arms of the crucified person were suspended directly above his head in supporting his body. But this is not the position of a person suspended from a cross. On the cross, a victim’s arms are extended at an angle of 60 to 70 degrees from the upright (stipes).

If arms were extended directly above the head breathing would unquestionably be difficult, but not where the arms are extended at a 60 to 70 degree angle from vertical. This has now been demonstrated by several experimental studies.

An Austrian radiologist, Hermann Moedder,6 suspended medical students by their wrists with their hands above their heads, less than 40 inches apart on a horizontal bar. In a few minutes the students became pale and the vital capacity of their lungs decreased from 5.2 to 1.5 liters. Their respiration became shallow, blood pressure decreased and pulse rate increased. Moedder concluded that orthostatic collapse, or inability to breathe, would occur in six minutes if the students were not allowed to stand. If the students could rest for a few minutes, alternating with three minutes of hanging, they could last longer. Moedder’s results confirmed that asphyxiation would occur if the crucified person (cruciarius) were suspended by his hands directly above his head. If Jesus’ arms had been suspended directly above his head, rather than extended at 60 to 70 degrees, then I would have no difficulty accepting the asphyxiation hypothesis as the cause of his death.

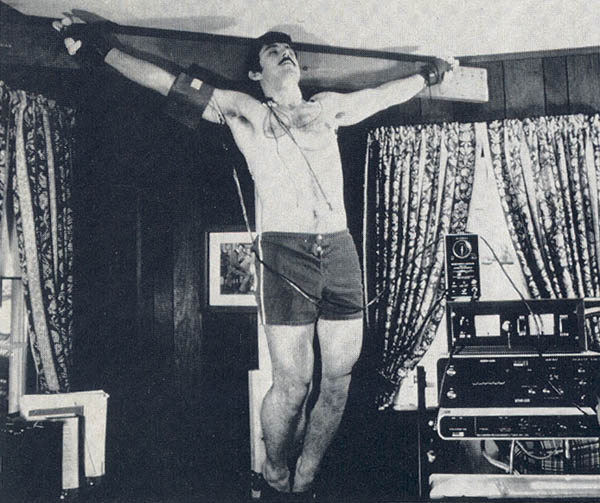

To test the validity of the asphyxiation hypothesis when the victim’s arm are extended at a 60 to 70 degree angle. I conducted the following experiment.

A very sturdy cross was constructed for me by the late Father Peter Weyland, S.V.D., with the vertical stipes measuring 92 inches high and the horizontal patibulum measuring 78 inches wide; the base was secured with a reinforced angle iron. A series of numbered holes was drilled through each arm of the patibulum to allow for different arm spans. Each hole was drilled in a slightly downward direction from front to back. In this way bolts could be inserted from back to front in an upward direction. Leather gauntlets were firmly laced around the gloved hand of the subject without restricting his blood supply. A hole was provided at the level of the base of the middle fingers so the gauntlet could be placed over the bolt that corresponded to the arm length of the volunteer. The angle of the bolt through the beam prevented slippage of the gauntlet. Volunteers between the ages of 20 and 35 were given physical examinations to obtain resting values for a variety of heart function indicators before suspension on the cross.a Heart monitoring electrodes were placed on the chests of the volunteers and attached to a stress testing apparatus that monitored the electrical patterns of the heart minute by minute. A blood pressure cuff was placed on one arm and attached to an electronic blood pressure recording unit, and an oximeter probe was attached to an ear and connected to an instrument that records the oxygen concentration of the blood at all times. Each volunteer was instructed to inform us of any breathing difficulties, pains of any kind, muscle cramps or any other problems. Volunteers were also requested not to attempt to raise their bodies by pushing their feet against the seat belt that secured them to the upright of the cross.

Each volunteer climbed up on a stool, placed his outstretched arms along the patibulum to line up the holes in the gauntlets with the respective holes on the patibulum corresponding to his arm length. Bolts were inserted into the appropriate holes through the back of the patibulum, then through the holes in the gauntlets. The stool was then carefully removed, allowing the volunteer to be fully suspended. The modified seat belt secured the feet to the vertical stipes of the cross. An emergency crash cart complete with resuscitation supplies was on hand to provide for the volunteer’s safety. Individuals were stationed to the right and left of the subject in case of an emergency.

During the period of suspension, ranging from 5 to 45 minutes, the following information was tabulated: muscle twitching, chest movements, skin color, sweating, breathing problems, and subjective information including pain, psychological feelings, etc. The heart-lung evaluation included examination with a stethoscope, measurement of arterial blood gases, ear oximeter readings, vital capacity, electrocardiograms, blood pressure and periodic blood chemistry screening. Douglas bag collections of the inhaled and exhaled air were taken at various intervals to determine relative oxygen content.

Following is a summary of the results of our experiments:

1. The angle formed by the outstretched arms of the subjects with the upright (stipes) varied between 60 and 70 degrees. This variation was due to differences in arm length and joint mobility from individual to individual. The series of holes placed in the cross piece (patibulum) allowed for maximum extension of arms of different lengths.

2. There was no visual evidence of breathing difficulties throughout the suspension.

3. All volunteers affirmed that they had absolutely no trouble either inhaling or exhaling. A common complaint was a feeling of chest rigidity and leg cramps between 10 and 20 minutes into suspension. When this occurred the volunteer was allowed to straighten his legs for a few seconds by loosening the belt holding his feet and holding him around the legs instead.

4. The oxygen content of the blood either increased or remained constant.b

5. Marked sweating occurred at about six minutes in most volunteers.

6. The heart rate increased to 120 beats per minute, but there were no arrhythmias, or uneven beats. there were occasional rapid rates, as high as 175, but this decreased after, the volunteer recovered from his initial fright. The blood pressure increased to varying degrees in everyone, depending on his state of conditioning. The electrocardiogram only showed muscle tremors and no cardiac abnormalities.

7. The backs of the volunteers never touched the cross except in the shoulder region, where contact was slight. Pain in the shoulder caused many volunteers to arch their bodies so that the top of the head touched the stipes, thereby relieving some of the pain. None of the volunteers attempted to push up to facilitate breathing, except when requested to do so.

8. When the volunteers were requested to push themselves up, their wrist angle did not change; instead their arms naturally flexed at the elbows.

These experiments overwhelmingly disprove Barbet’s asphyxiation theory.

Barbet offered two other arguments to support his asphyxiation hypothesis. The first concerned the observation that sometimes the crucified victim’s legs were broken while he hung on the cross. The purpose, according to Barbet, of crurifragium, breaking the legs of the victims on the cross, was to prevent the victim from raising his body in order to breathe.

We know from the Book of John that “the soldiers came and broke the legs of the first [thief] and of the other who was crucified with him. But when they came to Jesus and saw that he was already dead, they did not break his legs” (John 19:32–33). Although crurifragium was inflicted on the two thieves, Jesus’ more rapid death seems to have saved him from this cruel act.

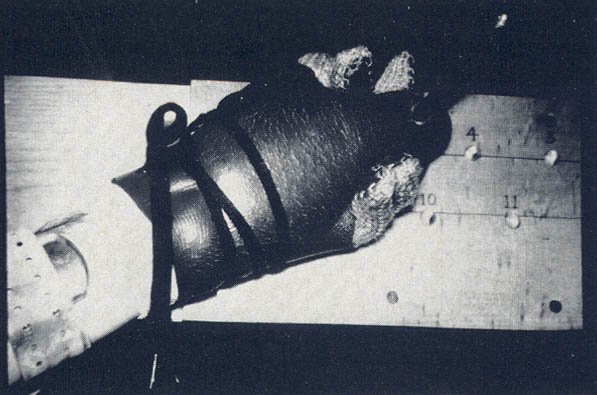

We have one piece of striking evidence of crurifragium from a tomb in Jerusalem, at Giv‘at ha-Mivtar, which was excavated in 1969–1970.7 The remains of a young Jew who died in the early first century A.D. were found in an ossuary, or bone box, used for secondary burial. It was customary during this period to collect the bones of the deceased after the body had been buried for almost a year and the flesh had decomposed. Among the bones in this ossuary were two that were pinned together by a large iron nail. A wooden plaque less than 1 inch thick was also attached to the bones by the nail. These nailed bones are the only physical evidence of crucifixion ever found. Two teams of investigators in Jerusalem, one led by Nico Haas8 and a later one led by Joseph zias and Eliezer Sekeles,9 have studied and reported on these bones.

The crucified man’s right tibia, the larger of the two bones in the lower leg, was also available for study. The bone had been brutally fractured into large, sharp slivers. Haas concludes that the fracture was caused by a single, strong blow to the legs, which were lying, pressed together, across the sharp edge of the wooden cross. The angle of the fracture, Haas notes, is proof that the bones were bent against one edge of the cross in a semiflexed position.

Zias and Sekeles disagree with Haas. They say that the legs hung in an extended position along the vertical stipes, with one leg nailed to each side of it. They also propose that not one, but multiple blows were administered to the legs.c

How do these differing interpretations relate to asphyxiation? Not at all. Whether the victim’s legs were in the flexed position with knees bent or in the extended position straddling the vertical wooden support, breaking the legs could not have prevented him from raising his torso to breathe. In the flexed position the torso was already raised to the maximum, and breaking the legs could not have prevented the crucified person from easing his breathing by pushing up. In the straddling position the victim could not have extended his legs farther so as to raise his upper body; therefore crurifragium was ineffective in accelerating asphyxiation. Whether there were multiple blows or a single one is also unrelated to asphyxiation.

More important, crurifragium is irrelevant to the asphyxiation theory because it is arm position that dominates the breathing function of the crucified victim. If arms are outstretched on the cross at 60 to 70 degrees to the vertical, the victim can breathe with relative ease, whether or not his legs are broken.

Barbet’s final argument for asphyxiation as a cause of death focuses on a peculiar double blood-flow pattern on the Shroud of Turin.10 At the outset, one should understand that since authenticity of the Shroud of Turin is at best controversial,d this observation cannot be used as scientific evidence. However, even if the shroud were authentic, the double blood-flow pattern is ridiculous evidence for supporting the asphyxiation theory. Here’s why.

The bifurcation pattern on the hand-wound image of the shroud was interpreted by Barbet as representing two positions that Jesus assumed in order to breathe during the time he was on the cross. He postulated, based on observations made at Dachau, that Jesus was unable to exhale as he hung on the cross; the inhaled air was trapped. Therefore, Jesus pushed up with his feet in order to expel the air from his lungs, and by so doing he changed the position of his nailed hands, causing the blood-stream flow from his wound to shift. Hence, according to this notion, the double blood-stream pattern appeared on the shroud. The reason why this interpretation of the bifurcation pattern is so improbable is because this pattern is located on the back of the hand—pressed against the cross—not on the front. How in the world can you get a perfect double flow of blood on the back of the hand if it is against the cross? Another important point that militates against the two positions of the hand causing a “double flow of blood” is the evidence from my experiment that the wrist does not change its angle even if the victim had to raise himself in order to breathe. The reason: The arms bend at the elbows and not at the wrists.

Having refuted the asphyxiation theory to explain Jesus’ death on the cross we are left with the question, What was the cause of his death?

A careful reconstruction of all of the facts surrounding the death of Jesus leaves little doubt that Jesus died from shock.

Shock, regardless of its cause, is defined as a constellation of symptoms, characterized by low blood pressure and reduced blood flow to cells and tissues. Shock leads to an imbalance between the metabolic needs of vital organs and the blood flow available to supply those needs. At first the injury to organs is reversible, but if shock continues it leads to irreversible cell and organ injury and eventually to death. There are a number of different types of shock, displaying different symptoms and initiated by a variety of factors.

To understand how Jesus came to be in shock, it is essential to examine some of the events related in the Gospels—particularly those directly affecting Jesus’ physical state—during the hours immediately before his crucifixion.

Matthew 26 relates that Jesus went with his disciples to a place called Gethsemane. He said to them, “‘My soul is very sorrowful, even to death; remain here and watch with me.’ And going a little farther he fell on his face and prayed” (Matthew 26:38–39). (Luke, describing Jesus’ agony in the Garden of Gethsemane says that Jesus “prayed more earnestly. And his sweat became like great drops of blood falling down to the ground” [Luke 22:44]). After he had prayed three times, Jesus said, “‘Rise, let us be going; see, my betrayer is at hand’” (Matthew 26:46). Then a crowd with swords and clubs “came up and laid hands on Jesus and seized him” (Matthew 26:50) and led him to the high priest. “Then they spat in [Jesus’] face, and struck him; and some slapped him” (Matthew 26:67). When the morning came “they bound [Jesus] and led him away and delivered him to Pilate the governor” (Matthew 27:2). Thereafter, Jesus was scourged and delivered to be crucified. Then the soldiers of the governor took Jesus into the praetorium, stripped him, put a scarlet robe upon him and “plaiting a crown of thorns they put it on his head and put a reed in his right hand. … And they spat upon him, and took the reed and struck him on the head. And when they had mocked him, they stripped him of the robe, and put his own clothes on him, and led him away to crucify him” (Matthew 27:29–31). The Gospel of John relates that Jesus “went out, bearing his own cross, to the place called the place of a skull, which is called in Hebrew Golgotha” (John 19:17).

What might have been the physiological effects on Jesus of the events of his last hours?

Let us try to imagine the physical changes experienced by Jesus during the ordeal before his death. His severe mental anguish in the Garden caused some loss in blood volume both from perspiration and from hematidrosis (sweating of blood) and provoked marked weakness.

After his arrest, Jesus was scourged by Pilate’s soldiers utilizing a flagrum composed of leather tails bearing metal weights or bone at the tips. As the flagrum was swung at Jesus’ flesh, its tips penetrated his skin, causing trauma to the nerves, muscles and skin. Jesus became exhausted, with shivering, severe sweating, frequent seizures and a craving for water. Hypovolemia, or loss of fluid, occurred as a result of sweating, blood loss and pleural effusion (the early stage of fluid accumulation around the lungs) from the trauma caused by the scourging. It is likely that even before reaching Golgotha, Jesus entered a state of traumatic shock brought about by the scourging,11 by the irritation of the nerves of the scalp by the cap of thorns from the Syrian Christ Thorn plant, and by being struck several times.

As Jesus trudged up the hill to Golgotha in the hot sun, sometimes carrying the crosspiece on his shoulders, sometimes falling under its weight, being struck as he moved along his painful route, water loss continued and his condition of shock worsened. Upon reaching the crest of Golgotha, Jesus was nailed to the cross with large, square iron nails driven through both hands into the cross. The probable resulting damage to the sensory branches of the median nerve caused a pain known medically as causalgia, one of the most exquisite pains ever experienced. The nails through the feet also elicited great pain. Both injuries caused additional traumatic shock and hypovolemia, or water loss. The hours on the cross, with the weight of the body pressing on the nails in the hands and feet caused episodes of excruciating agony every time Jesus moved. Traumatic shock would have been exacerbated by these episodes and by the unrelenting pain in the chest wall from the scourging. The excessive sweating induced by the ongoing trauma and by the hot sun would have further reduced blood volume, causing hypovolemic shock.12

Shock is unquestionably the cause of Jesus’ death on the cross. This was even discussed in Barbet’s book that presented his asphyxiation theory.13 In Appendix II (page 175), a dissenting note by the surgeon P. J. Smith appears, in which Dr. Smith writes: “I am of the opinion that there is overwhelming evidence that Christ died from heart failure due to extreme shock caused by exhaustion, pain and loss of blood.”

The next question to which we turn is, how was Jesus nailed to the cross? More specifically, what was the anatomical location of the hand wound? Barbet concluded, after performing some experiments, that the palms of the hands could not support the weight of the body.

For centuries, most devout Christians believed that the nails passed through the palms of the hands into the patibulum (crosspiece) of the cross. Even Justus Lipsius, the renowned 15th-century classical scholar from the University of Louvain,14 related that it was the hands that were transfixed in crucifixion, and artists’ early crucifixes showed the nails through the center of the palms.

To prove his point, however, Barbet nailed the hands of freshly amputated arms and suspended weights on the opposite ends of them. He found that the nail tore through the hand and emerged between the fingers when a weight of about 88 pounds was added with concomitant jerking of the arm. Mathematical computationse indicated that there is a pull greatly in excess of the weight of the body on each hand; Barbet therefore concluded that the palm was definitely not the place where the hands were nailed to the patibulum of the cross, and he looked for a stronger area.

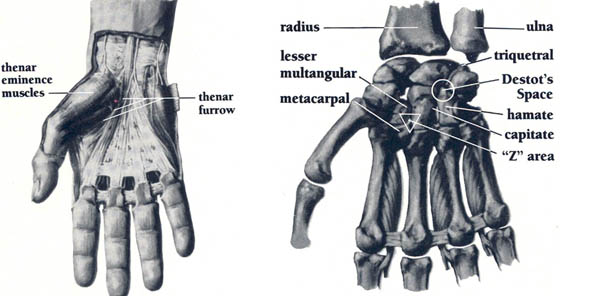

Barbet selected the wrist area as the site. He interpreted the hand wound image on the Shroud of Turin as passing through the wrist. His hypothesis was propounded to lend authenticity to the shroud. Barbet also experimented by driving square nails with sides measuring 1/3 of an inch through the wrist of a freshly amputated arm at a point he interpreted as corresponding to the site on the Turin shroud. Barbet reported that the nails always found a natural path through an anatomical area called Destot’s Space, a free space, defined by Barbet “in the middle of the bones of the wrists … bounded by the capitate, the semilunar, the triquetral and the hamate bones.” Barbet indicated that this path into Destot’s Space corresponded to the hand wound image shown on the Turin shroud.

Shroud devotees all over the world accepted this new explanation and inundated the literature with articles relating that the nails passed through the wrists of Jesus and not the palms. Even in the controversial film The Last Temptation of Christ, the nails pass through the wrists rather than the palms of Jesus’ hands. Barbet’s observations appear to be the primary reason why most of the world literature currently has adopted the wrists as the site of fixation to the cross and has abandoned the palms of the hands.

But, unfortunately, Barbet’s conclusion is again incorrect.

In fact, there are four possible sites for fixation, each of which would provide excellent support without any danger of pulling through the hands and are also in full accord with scriptural and early historic accounts. These include the upper part of the palm, the ulnar (small finger) side of the wrist, the radial (thumb) side of the wrist, and the region between the distal radius and ulnar bones in the forearm. All of these areas are extremely strong, being capable of holding many hundreds of pounds.

Scripture specifically indicates that Jesus was nailed through his hands: “See my hands and My feet, that it is I myself” (Luke 24:39) and “He showed them his hands and side … Then he said to Thomas, ‘Put your finger here, and see my hands …’” (John 20:20–27). The word “hand” has always been defined anatomically as a composite of the fingers, palm, dorsum (back of the hand) and wrist. Hence, scriptural references to “hand” do not preclude the possibility that the place of attachment was the wrist. To the layperson, however, “hand” refers to the front and back of the palm and fingers and does not include the wrist.

Barbet claimed that the soldiers carrying out crucifixions were trained experts who would know precisely where Destot’s Space was located and would have used it routinely. This hardly seems likely, especially since Barbet himself misidentified the location of Destot’s Space.f Moreover, early historical accounts indicate that crucifixion was done in many different ways.

Destot’s Space—properly understood—is one of the four areas that could provide fixation to the cross, but certainly not the only one.

Barbet rejected the palm of the hand as the location for nailing to the cross because in his experiments with cadaver hands, the flesh ripped. It is true that the central area of the palm of the hand could not support the body on the cross. But there is another area of the palm that could support the body on the cross. It is located in the upper part of the palm. Attachment by the palm of the hand has the advantage of being the location that most people through the centuries have pictured for the crucifixion, based on scriptural reference to “hand.” Second, it is where artists depicted the nails. Third, it is where most of the stigmatists, whose bodies developed Christ-like bleeding wounds, like St. Francis of Assisi, Padre Pio, Theresa of Konnersruth, St. Catherine of Sienna, Catherine of Ricci, Louise Lateau, etc., throughout the centuries have displayed their wounds.g

Anatomically the explanation is this: In the upper part of the palm there is a path into an area between the base of the hand and the back of the wrist that would support many hundreds of pounds. To locate it, open your hand, palm up. You will notice a bulky prominence extending into the hand from the base of the thumb. This mass, the thenar eminence muscles, causes the thumb to flex into the palm. Now touch your thumb to the tip of your little finger. You will note a deep furrow at the base of the thenar eminence muscles called the thenar furrow.

If a nail is driven into this furrow, a few centimeters from where the furrow begins at the wrist, with the point of the nail angled at 10 to 15 degrees toward the wrist and slightly toward the thumb, the nail inclines naturally to enter a space created by the configuration of three bones: the metacarpal bone of the index finger and the capitate and lesser multangular bones of the carpus (wrist). We have named this space the “Z” area. The “Z” area expands as the nail passes through and exits.

I demonstrated this “Z” area over 30 years ago in the human anatomy dissection laboratory. Dissection of the area, after passage of a nail, revealed that no bones were broken. A striking unrehearsed event in the county medical examiner’s office that I direct confirmed this a few years ago. A young lady had been brutally stabbed over her entire body. At autopsy, I found a defense wound on her hand where she had raised her hand to protect her face from the vicious onslaught Examination of the hand wound revealed that she was stabbed in the thenar furrow in the palm of the hand; the knife passed through the “Z” area and the point exited at the back of the wrist about where it joins the hand. X-rays of the area showed no broken bones.

In 1598, Monsignor Alfonso Paleotto, Archbishop of Bologna published a theory15 that the nail could have entered the upper part of Jesus’ palm obliquely, and, pointing toward the arm, emerged as I indicated above.

Barbet severely criticized Paleotto’s hypothesis as “anatomically impossible. …” Barbet’s remark, of course, is absolute nonsense in view of my studies in the anatomical dissection lab and of the stabbing case from the Rockland County, New York, medical examiner’s office.

In short, Jesus died from shock brought on by the traumatic physical events of his last hours, before and after he was nailed to the cross. Barbet’s asphyxiation theory is completely untenable.

The upper part of the palm of the hand is the most plausible of the regions where Jesus might have been nailed to the cross. This area can easily support the weight of the body, assures that no bones are broken, marks the location where most people since the time of Jesus believed it to be, and is in accord with the earliest artistic and historical accounts. The radial and ulnar sides of the wrist and the area in the forearm between the radius and ulna bones, however, cannot be fully excluded because they are very strong areas, and are not incompatible with Scripture. But they do seem to be less likely.

MLA Citation

Footnotes

This examination included: a 12-lead electrocardiogram, pulse rate, blood pressure, auscultatory examination, vital capacity and ear oximetry, arterial blood gases and venous blood chemistries.

Visual observations and Douglas bag studies measured the amount of air expired each minute and the relative oxygen content of the expired air. Both of these measurements determined that the oxygen increase occurred when hyperventilation began after four minutes of hanging, with abdominal breathing at a rate about four to five times normal.

Zias and Sekeles suggest that the blows may have been administered after death, which would, of course, make the crurifragium irrelevant to the victim’s breathing.

Since this article was written, the shroud has been shown to be a medieval forgery. The results of recent radiocarbon tests on small pieces of the shroud and comments about these tests by the author and other experts are reported in the sidebar to this article.

Using the formula—the pull on each hand is equal to twice the cosine of the angle that the arms make with the vertical.

Barbet located Destot’s Space directly under the hand wound on the shroud. This wound appears on the radial, or thumb, side of the wrist. In fact, Destot’s Space is on the ulnar, or small finger, side of the wrist—opposite to the location of the shroud’s hand wound. Barbet seems to have become confused about the shroud wound location; he demonstrated in several ways that Jesus was nailed through the small finger side of the wrist, all the while claiming that this location was that shown on the shroud.

Endnotes

A.A. LeBec, “A Physiological Study of the Passion of Our Lord Jesus Christ,” The Catholic Medical Guardian [London] 3 (1925), p. 26; “Le Supplice de la Croix,” L’Evangile dans la Vie, April 1925.

R.W. Hynek, Science and the Holy Shroud (Chicago: Benedictine Press, 1936); The True Likeness (New York: Sheed and Ward, 1951).

Vassilios Tzaferis, “Crucifixion—The Archaeological Evidence,” BAR 11:01.

Nico Haas, “Anthropological Observations on the Skeletal Remains from Giv‘at ha-Mivtar,” Israel Exploration Journal (IEJ) 20 (1970), pp. 38–59.

Joseph Zias and Eliezer Sekeles, “The Crucified Man from Giv‘at ha-Mivtar,” IEJ 35 (1985), pp. 22–27; Hershel Shanks, “New Analysis of the Crucified Mail,” BAR 11:06.

W.B. Primrose, “A Surgeon Looks at the Crucifixion,” Hibbert Journal 47 (1949), pp. 382–388; S.M. Tenney, “On Death by Crucifixion,” American Heart Journal 68 (1964), pp. 286–287.

For an in-depth discussion of the mechanisms of shock invoked during crucifixion, from initiation to death, see my article “Death by Crucifixion” published in the Canadian Society of Forensic Sciences Journal (vol. 17 [1984], pp. 1–13). My research findings and conclusions were presented in a paper entitled “Death by Crucifixion” before the Forensic Pathology Section of the American Academy of Forensic Sciences (35th Annual Meeting, Cincinnati, Ohio, Feb. 19, 1983). Many pathologists indicated agreement with my conclusions, and not a single forensic pathologist challenged any of the findings or conclusions.

Justus Lipsius, “De Cruci Libri tres. as sacrum profanamque historiam utiles,” Opera Omnia, Book 3 (Antwerp, 1614).