Nineveh and Its Remains: A Narrative of an Expedition to Assyria During the Years 1845, 1846, & 1847

Austen Henry Layard

(Guilford, CT: Lyons Press, 2001; this revised abridgment orig. published 1882) 384 pp., $16.95

“Wasted is Nineveh; who will bemoan her?”

With this prediction, the Old Testament prophet Nahum consigned the great Assyrian city of Nineveh to the dustbin of history—a prophecy fulfilled by the city’s destruction near the end of the seventh century B.C. and the gradual disappearance of its ruins under the debris of ensuing centuries. For almost two and a half millennia, Nineveh was little more than a name. No one even knew whether the great Assyrian capital ever really existed.

Then, a little more than 150 years ago, a young English lawyer and adventurer, Austen Henry Layard, began excavations at the site of Nimrud in what is now northern Iraq. He promptly and proudly—and, as we shall see, at first mistakenly—claimed to have discovered Nineveh’s remains.a

Layard’s account of his 1845–1847 expedition to Assyria, Nineveh and Its Remains (1849), generated tremendous excitement in Europe. The London Times hailed it as “the most extraordinary work of the present age.” And the book had staying power. In 1851 Layard published an abridged version under the title A Popular Account of Discoveries at Nineveh. Another version of the abridgment—with updated footnotes and new material from Layard’s 1853 book about his second expedition to Mesopotamia (Discoveries in the Ruins of Nineveh and Babylon)—was published in 1867. In 1882 Layard published yet another edition of the abridgment, again under the title Nineveh and Its Remains, which has recently been reprinted by the Lyons Press. “Layard’s masterpiece,” notes archaeologist Brian Fagan in his introduction to this volume, “has never gone out of print.”

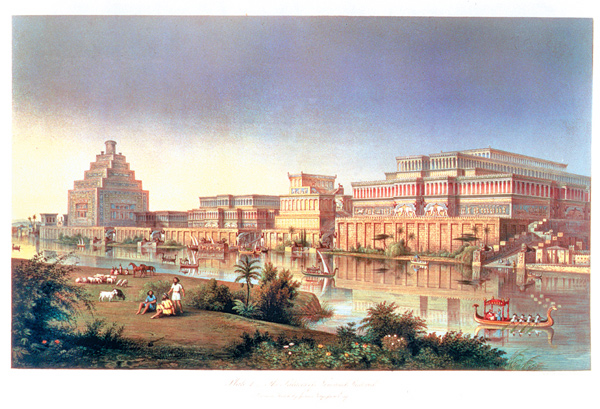

Part of what made the book a best seller in its own time, and keeps it selling today, is its eminent readability. Layard wrote with verve and skill. Near the end of Nineveh and Its Remains, for example, he describes the dazzling experience of someone who, “in the days of old, entered for the first time the abode of the Assyrian kings”:

Passing through a portal guarded by colossal lions or bulls, he [the imaginary ancient visitor] found himself surrounded by the sculptured records of the empire. Battles, sieges, triumphs, the exploits of the chase, and the ceremonies of religion, were portrayed on the walls—sculptured in alabaster, and painted in gorgeous colours. Above the sculptures were painted other events—the king, attended by his eunuchs and warriors, receiving his prisoners, entering into alliances with distant monarchs, or performing holy rites.

Layard does not give the typical dry-as-dust excavation report; rather, he offers a recreation (albeit with distortions) of the Assyrian world. In another passage, he vividly depicts the past and present surroundings of a pair of mysterious, colossal guardian lions:

For twenty-five centuries they had been hidden from the eye of man, and they now stood forth once more in their ancient majesty. But how changed was the scene around them! The luxury and civilisation of a mighty nation had given place to the wretchedness and ignorance of a few half-barbarous tribes. The wealth of temples, and the riches of great cities, had been succeeded by ruins and shapeless heaps of earth. Above the spacious hall in which they stood, the plough had passed and the corn now waved.

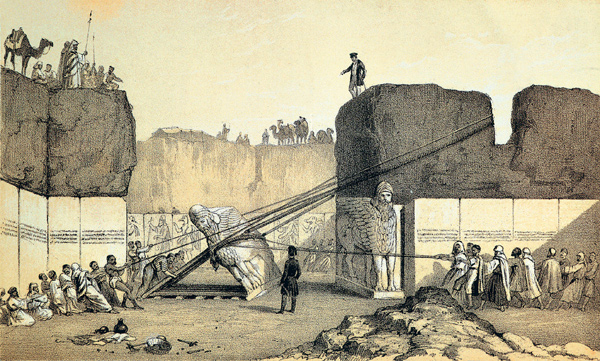

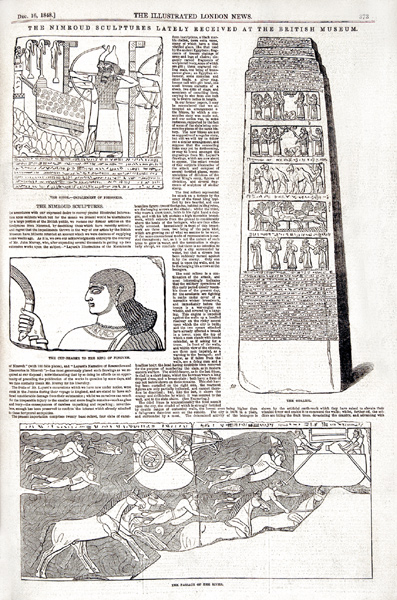

To give readers a tangible sense of this ancient world, Layard also made effective use of visual images. Highly skilled at drawing, he carefully recorded material he uncovered and sights he encountered with on-the-spot sketches. (Many popular works of the time, such as most of the novels of Dickens and Thackeray, routinely included illustrations; and the weekly periodical Illustrated London News specialized in engravings of contemporary scenes.) The drawings and vivid prose of Layard’s Nineveh and Its Remains instill in readers a vibrant sense of excitement as a vanished civilization is gradually released from the earth.1

For 19th-century readers, Layard’s material provided a kind of exotic, dreamlike adventure. On breaks from excavations, he explored different parts of the Turkish-ruled land where he was living. He visited Bedouin in their tents, Nestorian Christians in the mountains, and the Yezidis—known as “Worshippers of the Devil”—at “their great periodical feast.” Layard was as adept in providing both verbal and visual portraits of contemporaneous peoples—especially peoples who seemed remote from the mainstream of history—as he was in bringing the ancient world to life. In an era without National Geographic or the Discovery Channel, Layard’s reports on the strange, distant lives of such peoples must have seemed like compelling insights into human possibility and the human condition.

Then there was the Bible. Prior to Layard’s work, most Victorians had heard of Nineveh primarily from references to this Assyrian city in the Old Testament. It was the place, for instance, where God sent the prophet Jonah, who promptly took off in a different direction, toward Tarshish (possibly in modern Spainb), and was swallowed by “a great fish.” The story of Jonah sounds like just that, a story, a myth—so many people reasonably believed that Nineveh, too, might be just a myth.

By the mid-1840s, fossil discoveries (showing that many species had gone extinct) and geological evidence (showing that the earth was much older than had been thought) had begun to undercut the biblical account of Creation, shaking the faith of many Victorians accustomed to reading their Bible literally.2 New developments in biblical scholarship had also begun to reach England from Germany, especially the so-called “higher criticism,” which regarded the Bible as having human authors and which treated many biblical stories as legends, much like Greek or Nordic myths. The fact that the Bible was being studied like any other humanly constructed and therefore fallible document, with tools provided by secular scholarship rather than by religious faith, unsettled many traditional Christians who viewed it as a divinely revealed and historically accurate text.

In unearthing Nineveh, Layard provided indisputable confirmation of some elements in biblical stories at a time when skeptics were dismissing the Bible as a collection of fables. Layard showed that the mighty Assyrians had actually lived. An 1849 London Times review enthusiastically praised Nineveh and Its Remains for its “remarkable verification of our early biblical history.”

It was important that Layard had found Nineveh, not merely some obscure city no one cared about. Nineveh is mentioned almost 20 times in the Old Testament. It was a city that, at one point, God refused to destroy (thus angering Jonah) so that its people might reform themselves, but it was also the wicked and “bloody city” whose ultimate downfall was vividly foretold by the prophet Nahum. It was one of the capital cities of the great Assyrian Empire, which ruled over much of the Near East during the first half of the first millennium B.C.

Near the end of the eighth century B.C., the Assyrian ruler Sennacherib, whose capital was at Nineveh, laid siege to Jerusalem (then ruled by the Judahite king Hezekiah) but failed to capture the city.c According to the Bible, Sennacherib failed to take Jerusalem because 185,000 Assyrians were killed in one night by “the angel of the Lord” (2 Kings 19:35; Isaiah 37:36)—a providential escape celebrated in an 1815 poem by Byron titled “The Destruction of Sennacherib.” Some of Layard’s original readers may have had this biblical story etched into their minds by the memorable opening lines of Byron’s poem: “The Assyrian came down like a wolf on the fold, / And his cohorts were gleaming in purple and gold; / And the sheen of their spears was like stars on the sea, / When the blue wave rolls nightly on deep Galilee.”

Layard was not above using passions aroused by debates over the Bible’s historicity for his own purposes. As he was organizing material for Nineveh and Its Remains, one of his friends urged him to write “a whopper with lots of plates” and to “fish up old legends and anecdotes, and if you can by any means humbug people into the belief that you have established any points in the Bible, you are a made man.”3 Layard later wrote to another friend that “the book will be attractive particularly in America where there are so many scripture readers.”4

Sometimes Layard’s numerous parallels between the Bible and excavated Assyrian ruins seem like special pleading. Layard suggests, for example, that “Ezekiel, Jonah, and others of the prophets may have stood” before the “wonderful forms” of a pair of colossal winged lions with human heads.d After describing the ruined palace containing these colossi, Layard states that Ezekiel “may, indeed, have entered the very building.”

In making such claims, Layard was almost certainly pandering to religious interests. To give him his due, however, he was extremely skillful in making his discoveries meaningful within the intellectual climate of the day. He also understood that, from a Western perspective, he had arrived on ancient Assyrian ground at exactly the right historical moment:

The time of the discovery of these remains was singularly opportune. Had these palaces been exposed to view by chance some years before, no European would have been there to protect them from complete destruction, or to preserve a record of their existence. Had they been discovered a little later, it is highly probable that there would have been insurmountable objections to the removal of even any part of their contents.

Indeed, a century earlier few people would have been interested in the remains of a marginally important biblical people. And until the creation of the great European museums in the late 18th and early 19th centuries, such as the British Museum and the Louvre, there would not have been resources available to transport the reliefs and colossi to Europe.

Layard’s relics of Assyrian antiquity also carried a political meaning: Many Victorians saw an analogy between their own sense of national identity and the great Assyrian civilization Layard had brought to light. Like the United States today, Victorian Britain was proud—sometimes chauvinistically proud—of its successes, both at home and abroad.e In the mid-19th century, England was the dominant industrial power in the world. By the time Queen Victoria died in 1901, one fourth of the world’s population was part of the British empire. Not surprisingly perhaps, British Victorians readily identified with an ancient power that had dominated the then-known world.5

A review of Layard’s Discoveries in the Ruins of Nineveh and Babylon in Blackwood’s Magazine, for example, described Assyria as “the first of the so-called ‘universal’ empires,” of which England was the most recent manifestation:

The “meteor-flag” of England is the great object which, in these latter days, arrests the eye of the philosophic observer,—bringing over the seas, peopling continents and islands with civilised man,—and carrying the science, the religion, and the beneficent sway of Great Britain over an empire upon which the sun never sets.

The most spectacular of the artifacts brought to light by Layard were huge sculptures of man-headed winged lions and bulls, used in pairs at the entrances to Assyrian palaces and temples. Layard suggested to Sir Stratford Canning, the British ambassador to Constantinople who obtained permission from Turkish authorities for Layard to excavate and ship artifacts to England, that one of the colossal bull statues, among other items, should be sent to the British Museum. In an 1846 letter, the ambassador responded, “I quite agree with you that the Bull—the gigantic bull with a human head—is the very thing for a British museum;—I presume you mean as a type of John Bull.”6

This parallel between ancient and modern empires, however, raised a problem: It carried the unwelcome suggestion that Victorian civilization, too, might crumble. The specter of the decay of civilizations always hovered in the background of the bustling, progress-oriented, mid-19th-century British sensibility. Did Layard’s discovery of yet another great civilization reduced to ruin—along with Egypt, Greece and Rome—mean that decline and fall were the lot of humankind, and therefore of Britishkind? A review of Layard’s 1853 Discoveries in the Ruins of Nineveh and Babylon in the Illustrated London News made a special point to refute this possibility:

It is impossible—and impossible physically, as well as morally—that … after a lapse of ages five times as numerous as those which separate the present era from the era of Ninus [according to Greek legend, the first king of Assyria], the same shadows should envelop the memory of Victoria.

Perhaps this reviewer doth protest too much; the emphatic tone of this denial may well conceal a fear that decline and fall are indeed the lot of man. In any event, Layard had struck a nerve, for the fear of the collapse of civilizations recurs in writings about Nineveh in the 1850s. An article in the journal Household Words entitled “The Nineveh Bull,” for example, ends with a fanciful prediction by the bull himself: “[B]oast not, ye vainglorious creatures of an hour. I have outlived many mighty kingdoms, perchance I may be destined to survive one more” (February 8, 1851).

In the furor over Nineveh and Its Remains, it hardly mattered that Layard had not really identified the site of Nineveh. The principal site of his excavations, as reported in Nineveh and Its Remains, was actually the ancient Assyrian city of Kalhu (the modern mound of Nimrud), called Calah in the Bible (Genesis 10:11–12). Nineveh, in fact, lies beneath the mound of Kuyunjik, north of Nimrud and across the Tigris River from Mosul. Although Layard excavated briefly at Kuyunjik in 1846 and 1847, he did not recognize the site as Nineveh, largely because he was unable to read the cuneiform inscriptions he discovered.f

By 1853, when Layard published Discoveries in the Ruins of Nineveh and Babylon, which covered his second expedition to Mesopotamia (1849–1851), he was aware that cuneiform evidence pointed to Kuyunjik as ancient Nineveh. Nevertheless, the various editions of Nineveh and Its Remains, even the 1882 edition that is the basis of the modern reprint, continue to confuse Nimrud with Nineveh.

Despite this persistent error, Nineveh and Its Remains sold, and continues to sell. Its 19th-century popularity was clearly a measure of how much the ancient Assyrians meant to the Victorians. The fact that Layard’s discoveries continue to interest general readers today reflects our own 21st-century fascination with ancient civilization—and perhaps our fear that our civilization, too, may someday lie in ruins.

MLA Citation

Footnotes

For more on the 19th-century debate over Layard’s discoveries, see Mogens Trolle Larsen, “Europe Confronts Assyrian Art,” Archaeology Odyssey, January/February 2001.

On the possible relation between Tarshish and Spanish Tartessos, see the following articles in Archaeology Odyssey: Ricardo Olmos, “Warriors, Wolves and Women: The Art of the Iberians,” May/June 2003; and Sebastian Celestino and Carolina Lopez-Ruiz, “Sacred Precincts: A Tartessian Sanctuary in Ancient Spain,” November/December 2003.

See the following articles in Biblical Archaeology Review: Mordechai Cogan, “Sennacherib’s Siege of Jerusalem,” January/February 2001; William H. Shea, “Jerusalem Under Siege: Did Sennacherib Attack Twice?” November/December 1999; Dan Gill, “How They Met: Geology Solves Longstanding Mysteries of Hezekiah’s Tunnelers,” July/August 1994.

On the other hand, according to the late Elie Borowski (“Cherubim: God’s Throne?” Biblical Archaeology Review, July/August 1995), such composite creatures may have inspired the prophet Ezekiel’s vision of cherubim with human, leonine, bovine and avian features (Ezekiel 1:10). Layard similarly mentions “the resemblance of the winged human-headed lions and bulls and other symbolical figures [that he had unearthed] to those seen by Ezekiel in his vision.”

In Our Mutual Friend (1864–65), Charles Dickens satirized this kind of British Victorian smugness in the character of Mr. Podsnap, who “with his favourite right-arm flourish … put the rest of Europe and the whole of Asia, Africa, and America nowhere.”

When Layard first published Nineveh and Its Remains (1849), the Akkadian cuneiform script used by the Babylonians and Assyrians was only partially deciphered. In 1850, Henry Creswicke Rawlinson, an officer with the British East India Company who made a leading contribution to the script’s decipherment, told the Royal Asiatic Society that the Akkadian cuneiform’s phonetic irregularities made it impossible for him “to reduce it to a definite system” (quoted in Maurice Pope, The Story of Decipherment [London: Thames & Hudson, 1975 and 1999], pp. 113–114). In the mid-1850s, however, Rawlinson completed the decipherment, largely by working on texts found by Layard at (the real) Nineveh.

Endnotes

Layard’s sketches were put into final form for Nineveh and Its Remains by George Scharf, Jr. As Frederick N. Bohrer has pointed out, Scharf worked for Layard’s publisher and was “the primary artist for many of the book’s illustrations” (Orientalism and Visual Culture: Imagining Mesopotamia in Nineteenth-Century Europe [Cambridge University Press, 2003], p. 146).

When Charles Darwin’s Origin of Species (1859) appeared, this apparent conflict between science and religion became a crisis. However, earlier writers, including Darwin’s grandfather Erasmus Darwin, had broached some of the evolutionary ideas that Charles Darwin consolidated evidence for and applied to living species in terms of the theory of natural selection. One of Charles Darwin’s younger contemporaries, Alfred Russel Wallace, also independently formulated the theory of natural selection shortly before Darwin published Origin.

According to Shawn Malley, the British “desired to forge deep-rooted cultural associations with the impressive Assyrian world Layard had unearthed.” Layard’s accomplishments were “extolled in the periodical press as a mission to locate Assyria in a cultural continuum crowned by Great Britain” (“Austen Henry Layard and the Periodical Press: Middle Eastern Archaeology and the Excavation of Cultural Identity in Mid-Nineteenth Century Britain,” Victorian Review 22.2 [1996], p. 158).