Pope Sixtus IV built the Sistine Chapel in Rome in 1475–1481 as his private chapel. The chapel, which bears the pope’s name, appears from the outside to be a fortlike rectangular structure. The interior of the chapel is a plain rectangular space 130 feet long and 45 feet wide with a shallow ceiling vault rising to a maximum height of 60 feet above the chapel floor. Six windows penetrate each of the long walls.

As we describe the Chapel paintings, turn to the pictures on the following pages.

The worshipper enters the chapel through its eastern side, on the narrow end of the rectangular structure. Directly opposite, at the other end of the chapel, is the altar and behind the altar, occupying western wall, is Michelangelo’s painting of the Last Judgment. The long north and south walls, on the right and left as one faces the altar, are covered with a series of paintings by several leading painters of 15th century: Botticelli, Perugino and others. On the south wall are scenes from the life of Christ; on the north wall are scenes from the life of Moses. Completely covering the vaulted ceiling are Michelangelo’s paintings of scenes from Genesis, accompanied by biblical and non-biblical figures (see ceiling plan).

The ceiling divides into four areas:

1. The backbone of the ceiling is a series of paintings of events from Genesis, alternating large ones and small, that runs down the long central axis. The series begins above the altar with “God Separating Light from Darkness,” proceeds through the Creation of the Sun, Moon and Planets, Congregation of the Waters, Creation name, Adam, Creation of Eve, the Temptation and Expulsion from the Garden of Eden, the Sacrifice of Noah, the Flood, and ends above the doorway, opposite the altar, with “Drunkenness of Noah.”

2. Flanking the small paintings in the center of the ceiling, and often overlapping the edges of the large ones, are 20 nude young men, or ignudi, holding ribbons and garlands of oak leaves (the emblem of the pope’s family, the delle Rovere). Painted medallions hang from the ribbons.

3. Images of the prophets and of the sibylsa alternate between the spandrels of the windows, in the roughly triangular areas with the point at the feet of the subjects. The prophets represented are Zecharias, Joel, Ezekiel, Jeremiah, Jonah, Daniel and Isaiah. The thrones of the sibyls and prophets are flanked by pairs of putti, or nude cherubs, in active poses but painted to look like sculptures. Flanking these putti are bronze-colored nude male figures in various poses and with no indication of identification or function.

4. In the spandrels—flat, roughly triangular areas between the tops of adjoining arches—and lunettes—crescent-shaped areas above the arched windows—are series Christ’s ancestors (see

The painted architecture on the ceiling is a fundamental part of the artist’s conception. Michelangelo painted a cornice around all four sides of the ceiling’s central area, enclosing within it the ignudi (see detail of ignudi), areas or male nudes, and the painted scenes from Genesis. The ignudi sit on blocks resting on the cornice; the prophets and the sibyls sit between the vertical pilasters that support the cornice; the pairs of putti stand or are pictorially “carved” against the pilasters.

Michelangelo’s ceiling is not illusionistic in the sense characteristic of later Baroque vault paintings. There is never a sense that the vault has been opened up to a vision of a scene that lies beyond it. Rather all is clearly on the surface of the ceiling vault.

The ceiling must be seen both longitudinally and transversely. The events from Genesis occupy the longitudinal axis; the rest is designed to be seen from one side as or the other. There is no single point of view from which the entire ceiling should be viewed; each segment of the chapel should be seen from its own point of view and the spectator is required to move processionally through the chapel to experience it completely. Unlike Baroque ceilings, which are coherent from one point only, the parts of Michelangelo’s ceiling beyond the spectator’s immediate vantage point are progressively more foreshortened but not misshapen. Nevertheless, the visitor feels the necessity to press forward down the chapel in order to see the whole unfolding and to grasp the successive levels of the composition.

Sistine Chapel ceiling

As almost any visitor to the chapel can testify, the first and overwhelming impression is of the gigantic representations of the prophets and the sibyls. It is not simply their size that is so impressive, but the eloquence of their forms and attitudes and their emotional range. The 12 figures seem to embody the full range of human character and personality: male and female, beauty and ugliness, passion and despair, reflection and action.

The prophets and the sibyls are the only figures that appear to exist within the actual space of the chapel itself. Although they are closely related to the painted architecture on the ceiling they seem to protrude into the space of the chapel.

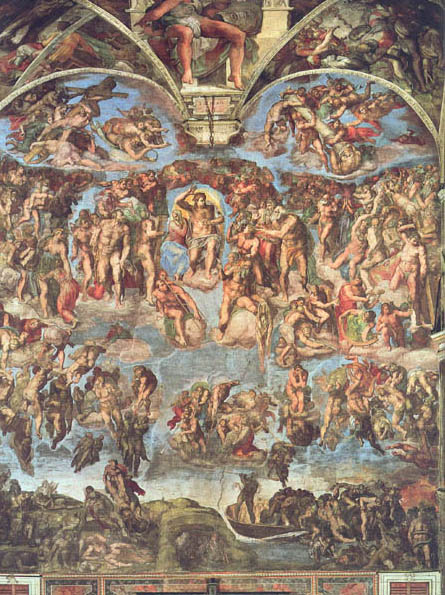

A quarter of a century passed between Michelangelo’s painting of the Sistine ceiling and his painting of the “Last Judgment” on the western wall of the chapel, next to the altar. When Michelangelo painted the ceiling, he was charged with an intricate program of subjects, whereas with the later wall he addressed a single space and a single subject. There is no continuation of pattern from ceiling to wall, but, nevertheless, the two paintings are deeply unified.

Unlike the ceiling, the wall of the “Last Judgment” has no painted architectural framework. It is a single area, seen instantly and whole from any point within the chapel; Michelangelo designed the painting so that its impact is immediate and powerful, even from the farthest point of view at the entrance.

There are several distinct zones in the “Last Judgment”: The lowest zone centers on the mouth of Hell; it is not clear whether we are on the outside looking in (as is most probable) or on the inside looking out. The space to the left is taken up with the resurrection of the dead. The right-hand side depicts the transport of souls to Hell.

A narrow strip of sky separates the second level from the lowest level. On the left of the second level, the souls of the redeemed float upward or are drawn upward into the realm of the blessed above; on the right, a group of the damned are attempting to break out and are being driven back by angels and dragged back by demons. The center of this second zone is occupied by the angels of the Last Judgment blowing trumpets.

The third zone—and the entire painting—is dominated by the tremendous figure of Jesus, right hand raised above his head, the left stretched across his body. Mary draws herself protectively under the mighty upraised right arm.

When Michelangelo returned to the western wall 25 years after completing the ceiling, he connected the new work with the former one by means of the previously painted figure of the prophet Jonah, located on the top of the end wall above the altar. (The ceiling composition extended onto the upper portion of the vertical wall.) In the whole of the ceiling composition, no figure, except Jonah, shows any awareness of the events from Genesis painted along the central axis of the ceiling. The prophets and the sibyls attend to their own books; their attention may be directed outward or inward but never to the ceiling itself. Only Jonah reacts to the events portrayed; he falls backward in open-mouthed awe as he looks up directly at the figure of God separating light from darkness.

Looming above the altar, Jonah was the link between the altar and the ceiling in the original absence of any connecting link on the wall. When Michelangelo returned to paint the “Last Judgment,” on the wall, Jonah was there to use as the key link in the chain of relations Michelangelo established. A series of compositional movements connects the two paintings by means of the figure of Jonah. The most evident is the axial movement that begins at the bottom (in the mouth of Hell) immediately above the altar, goes up through the knot of trumpeting angels, across the open space between the two central saints, up through the dominant figure of Jesus, through the upflung hand to the pendentive, or curved wall, immediately beneath Jonah.

In the “Last judgment,” every movement, every gesture of every figure is directed toward the figure of Jesus. This is the primary unifying device in a widely dispersed composition; it is also a theological assertion. Traditionally, the “Last Judgment” is placed on the entrance wall of a church. Those entering the church, symbolizing the city of God, do so by metaphorically experiencing the Last Judgment. By placing the “Last Judgment” on the altar wall, opposite the entrance, Michelangelo transformed the traditional symbolism. The church became the pathway to redemption. The worshipper, moving from the entrance toward the altar, parallels the return to God on the ceiling. For the participant in the Mass, receiving the sacraments (representing the body and blood of Christ) at the altar begins the upward movement toward God, through Christ.

The action of the Mass at the altar in the Sistine Chapel, the paintings on the ceiling, the “Last Judgment” directly behind the altar, all are parts of the worshipper’s religious experience. In order to understand Michelangelo’s masterpieces in the Sistine Chapel, even the unbelieving spectator must try to become a sympathetic participant in this experience.

(For additional reading about the theology of the Sistine Chapel paintings, see “The Christology of Michelangelo: The Sistine Chapel,” by John W. Dixon, Jr. [Journal of the American Academy of Religion, Fall 1987, Volume LV/3], the source of the descriptive details in this article.)